Walter Sickert and Contemporary Drama

William Rough

The New Drama of the early 1900s had echoes in the paintings of Walter Sickert, who as a young man worked briefly as an actor. William Rough explores points of comparison between contemporary plays and the painter’s sometimes highly staged compositions.

‘A painter is guided and pushed by his surroundings very much as an actor is.’

Walter Sickert, ‘The New English and After’, New Age, 2 June 1910.1

Walter Sickert, ‘The New English and After’, New Age, 2 June 1910.1

It is perhaps no great surprise to discover that Walter Sickert's paintings frequently depict topics and themes associated with contemporary theatre. Sickert worked as an actor during the late 1870s and early 1880s, during which he had a brief spell at Henry Irving's Lyceum and toured with George Rignold's and William and Madge Kendal's companies. Indeed, his interest in the theatre as a source and subject matter for his paintings has long been acknowledged, yet its influence during his Camden Town period has remained surprisingly overlooked. If, however, we consider Sickert’s works from the period of his return to London in 1905 to the outbreak of the Great War in 1914, a number of thematic and compositional similarities emerge that reveal a curious relationship with the developing New Drama and contemporary drama in general.

Sickert’s early career as an actor helped him foster a number of significant friendships and acquaintances with theatrical figures, including the playwright Arthur Wing Pinero and the actor Johnston Forbes-Robertson. In addition, his Paris links introduced him to the naturalist theatre of André Antoine’s Théâtre-Libre and Aurélien Lugné-Poë’s symbolist Théâtre de l’OEuvre (his friends Jacques-Émile Blanche and George Moore were regular attenders). Indeed, the Parisian theatre also provided a vital influence for the direction and staging of Harley Granville Barker and John Eugene Vedrenne’s management at London’s Royal Court Theatre between 1904 and 1907. The Court provided English audiences with their first experiences of avant-garde European works (by Maurice Maeterlinck, Henrik Ibsen and Gerhart Hauptmann) as well as a platform for British dramatists of the New Drama school, such as George Bernard Shaw, St John Hankin, John Galsworthy and Elizabeth Robins. The ideals of Antoine’s theatre, and subsequently Barker and Vedrenne’s, were perfectly summarised by the playwright Jean Jullien:

I believe that, as art is not simply nature, so theatre should not be simply life ... This is the only way to stage serious theatre ... in place of the curtain there must be a fourth wall, transparent for the audience, opaque for the actor ... A play is a slice of life artistically set on the stage ... a synthetic version of life achieved through art.2

Like the Théâtre-Libre, productions at the Court were characterised by their attention to psychological honesty as well as naturalistic set-design. Regarding the 1905 production of Barker’s The Voysey Inheritance, for example, the Era noted that it was ‘a pure joy to listen to dialogue so inevitably true to the commonplaces of everyday middle-class life’.3 Blanche, again, was a frequent visitor:

Many an evening my wife and I used to walk along Sloane Street from our hotel to the Court theatre in our ordinary clothes ... certain to meet people we knew, habitual lecture-goers, artists, theosophists.4

New Drama theatre was therefore a rich source of interest for Sickert’s contemporaries and was undoubtedly ripe for interpretation through a painter’s brush.

Contemporary drama and the spectre of Ibsen

As noted, the theatre of the New Drama was characterised by naturalistic sets, psychologically driven situations rather than elaborate plots, and a greater interest in realism and sincerity in acting – in contrast to the more typical visual spectacle of London’s middle class West End theatre productions. The New Drama was principally inspired by the successes of continental theatre, and particularly the plays of Ibsen. The Norwegian had cast a long shadow on the English stage since the 1880s, partly through the translations of his work by William Archer and Edmund Gosse as well as the 1891 production of Ghosts at J.T. Grien’s Independent Theatre (which Sickert may have attended).5 As George Bernard Shaw noted in 1895, so vital was Ibsen’s influence that producers were at risk of failing their audience if they did not recognise his importance: ‘In short, a modern manager need not produce The Wild Duck; but he must be very careful not to produce a play which will seem insipid and old-fashioned to playgoers who have seen The Wild Duck, even though they may have hissed it.’6

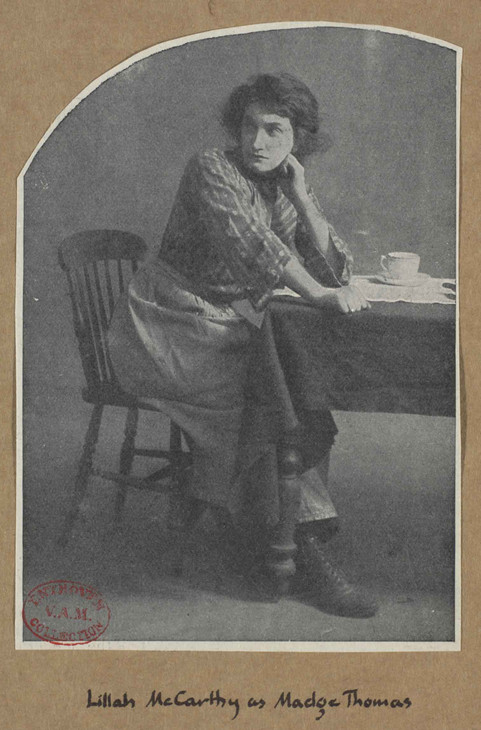

Lillah McCarthy as Madge Thomas in John Galsworthy's 'Strife' 1909

Theatre and Performance Collections, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Theatre and Performance Collections

Fig.1

Lillah McCarthy as Madge Thomas in John Galsworthy's 'Strife' 1909

Theatre and Performance Collections, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Theatre and Performance Collections

It is obviously quite impossible nowadays to produce thoughtful plays written by thoughtful people which do not bear some traces of the influence of the feminist movement – an influence which no modern writer, however much he may wish it, can entirely escape.7

New Drama also demonstrated a growing interest in class distinctions (seen particularly in the relocation and contrast between middle class and lower class environments and circumstances), such as Arthur Wing Pinero’s Mid-Channel (St James’s Theatre, September and October 1909), John Galsworthy’s Strife (Duke of York’s, Haymarket and the Adelphi theatres, March and April 1909, fig.1), Alfred Sutro’s The Perplexed Husband (Wyndham’s Theatre, September 1911, fig.2) and Harley Granville-Barker’s Waste (Imperial Theatre, November 1907). Two paintings, both held in Tate’s collection, Ennui c.1914 (Tate N03846, fig.4) and Off to the Pub 1911 (Tate N05430, fig.8), demonstrate the inspiration Sickert appears to have derived from these forms of theatre.

The problems of theatre photography

One of the difficulties in locating potential theatrical inspiration and visual sources for Sickert’s Camden Town images is that very few exist, at least in terms of photographs of avant-garde productions. It was rare for a play to be photographed mid-performance and contemporary photographs were usually staged to benefit the photographer’s requirements rather than to reflect an authentic record of the production. Those plays that were photographed were most often West End comedies, romances and melodramas – usually popular productions that had a long run. These images were widely disseminated through the popular press, including theatrical journals such as Play Pictorial and Playgoer and Society Illustrated as well as more general publications including the Daily Mirror, Daily Telegraph, Illustrated London News, Sketch and Tatler as well as on postcards and posters. The New Drama productions, on the other hand, typically lasted only for short runs and were performed to the ‘discerning’ playgoer rather than a wider audience.

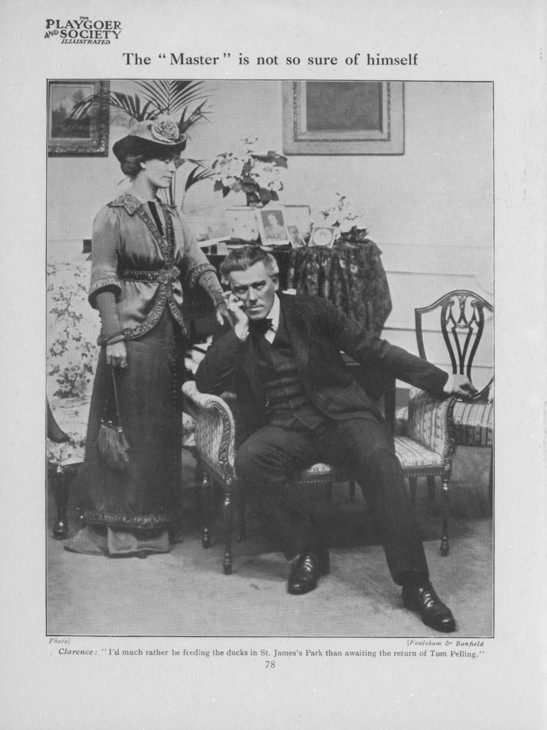

Henrietta Watson and E. Lyall Swete in Alfred Sutro's 'The Perplexed Husband' 1911

Theatre and Performance Collections, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Theatre and Performance Collections

Fig.2

Henrietta Watson and E. Lyall Swete in Alfred Sutro's 'The Perplexed Husband' 1911

Theatre and Performance Collections, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Theatre and Performance Collections

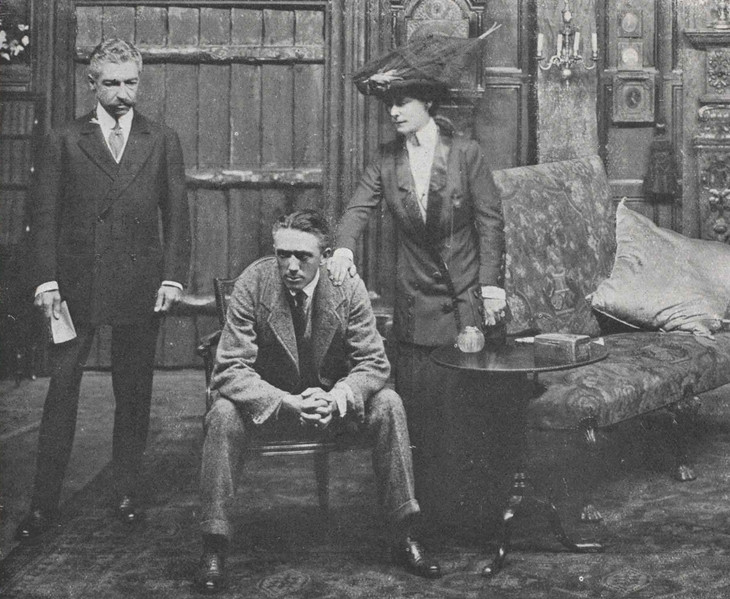

Sydney Valentine, Gerald Du Maurier and Lillian Braithwaite in George Paston's 'Nobody's Daughter' c.1910–11

Theatre and Performance Collections, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Theatre and Performance Collections

Fig.3

Sydney Valentine, Gerald Du Maurier and Lillian Braithwaite in George Paston's 'Nobody's Daughter' c.1910–11

Theatre and Performance Collections, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Theatre and Performance Collections

However, even photographs of West End productions provide valuable indications of potential visual inspiration for Sickert. Although depicting ‘lighter’ productions they provide a tantalising, albeit distilled, taste of modern theatrical stage conventions. Indeed, a series of visual compositional similarities emerge between Sickert’s images of domestic duets and the photographic records of productions, including an obvious shared interest in gesture, pose and body language. In addition, a recurring composition in theatrical photographs consists of contrasting seated and standing male and female figures with the subject directly addressing the viewer (figs.2 and 3).8 Ultimately, like Sickert’s paintings, these photographs are focused on visually interpreting the conflict and tension within relationships.

Unlike the earlier music hall portraits, such as Little Dot Hetherington at the Bedford Music Hall c.1888–9 (private collection)9 or The P.S. Wings in the O.P. Mirror c.1888–9 (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen),10 or later Shakespeare-related pieces like ‘The Taming of the Shrew’ c.1937 (private collection),11 during his Camden Town period Sickert’s inspiration derived not from copying directly from the stage, but from the general theatrical milieu of the time; from discussions among friends and acquaintances, and reviews and photographic depictions in newspapers and journals. In essence, Sickert became the stage-manager of his work, directing and choreographing his ‘cast’, choosing locations, arranging props and furnishings and suggesting narratives. Crucially, his interpretations expanded upon themes, compositions and subjects then prevalent on the London stage. This was only possible through his interest and knowledge of the traditions and development of contemporary theatre. As a result his Camden Town paintings reveal an unparalleled theatricality which has previously been neglected in readings of his work. While the theatrical experience remains ephemeral, Sickert has provided the viewer with a permanent impression of the visual and emotional experience of the Edwardian theatre.

Ennui: ‘dull minutes’ and ‘dead cigars’12

Ennui, featuring Sickert’s regular cast of ‘Hubby’ and Marie Hayes, with its concentration on a lower class domestic drama, setting and ambiguous narrative, perfectly complements the New Drama model and characterises Sickert’s work of the period (fig.4).13 While the writer Virginia Woolf’s famous description of Ennui’s ‘old publican’ suggests a novelistic source, it eclipses the artist’s more likely source of inspiration.14 Discussing the value of narrative Sickert famously stated, ‘All the greater draughtsmen tell a story’;15 however, the inspiration for this story lies on the stage rather than in the novel.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Ennui c.1914

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1524 x 1124 mm; frame: 1741 x 1340 x 110 mm

Tate N03846

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1924

© Tate

Fig.4

Walter Richard Sickert

Ennui c.1914

Tate N03846

© Tate

For a painter the challenge of depicting dialogue was naturally difficult. However, as the New Dramatists strove towards more naturalistic forms they underlined the importance of non-verbal communication. The intensity of a loaded silence or pause was as powerful as any speech, as Sickert’s friend the poet Arthur Symons noted: ‘Two people should be able to sit quietly in a room, without ever leaving their chairs, and to hold our attention breathless for as long as the playwright likes.’16

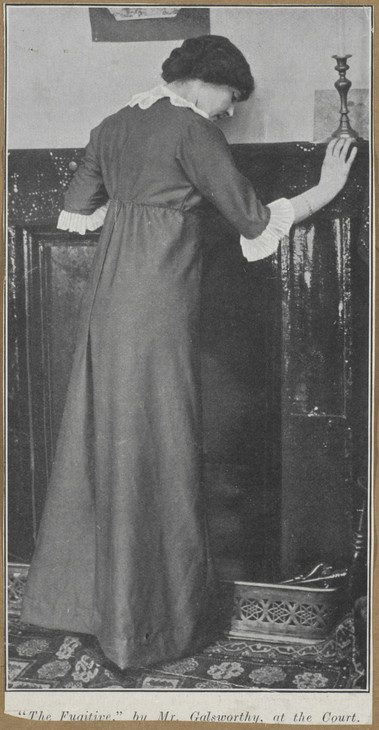

Irene Rooke as Clare Desmond in John Galsworthy's 'The Fugitive' 1913

Theatre and Performance Collections, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Theatre and Performance Collections

Fig.5

Irene Rooke as Clare Desmond in John Galsworthy's 'The Fugitive' 1913

Theatre and Performance Collections, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Theatre and Performance Collections

Malise: Mrs Desmond, there’s a whole world outside yours. Why don’t you spread your wings?

Clare: ... Then, I’ve no money, and I can’t do anything for a living, except serve in a shop. I shouldn’t be free, either; so what’s the good? Besides, I oughtn’t to have married if I wasn’t going to be happy. You see, I’m not a bit misunderstood or ill-treated. It’s only –

Malise: Prison. Break out!18

Clare: ... Then, I’ve no money, and I can’t do anything for a living, except serve in a shop. I shouldn’t be free, either; so what’s the good? Besides, I oughtn’t to have married if I wasn’t going to be happy. You see, I’m not a bit misunderstood or ill-treated. It’s only –

Malise: Prison. Break out!18

Not necessarily unsympathetic, Clare’s husband is nevertheless adamant about his wife’s duty:

George: The facts are that we’re married – for better or worse, and certain things are expected of us. It’s suicide for you, and folly for me, in my position to ignore that. You have all you can reasonably want; and I don’t – don’t wish for any change. If you could bring anything against me – if I drank, or knocked about town, or expected too much of you. I’m not unreasonable in any way, that I can see.19

The scene in which Clare requests a separation from George tellingly concludes with her husband asserting his authority, both physically and emotionally, as the stage directions make clear: ‘In the gleam of light Clare is standing, unhooking a necklet. He goes in, shutting the door behind him with a thud.’20 Clare’s lack of independent wealth is symbolically echoed in the constrained spaces of Ennui’s lower class interior. In the painting, the female figure appears equally trapped – emotionally and literally, as well as financially and psychologically – simply another object owned by the man.

In addition to The Fugitive, George Bernard Shaw’s Getting Married (first produced at the Haymarket Theatre, 12 May 1908) discusses a similarly disintegrating relationship. Collins, a tradesman, notes his sister-in-law’s predilection for short-lived affairs:

She didn’t seem to have any control over herself when she fell in love. She would mope for a couple of days, crying about nothing; and then she would up and say – no matter who was there to hear her – ‘I must go to him, George’; and away she would go from her home and her husband without with-your-leave or by-your-leave.21

The relationship represented in Ennui also bears a subtle similarity to that of the dull marriage of Polina and Shamrayev in Chekhov’s The Seagull (produced by the Adelphi Play Society at Gertrude Kingston’s Little Theatre in 1912). Nina’s self-proclaimed identification with the dead seagull in Chekhov’s play echoes Sickert’s inclusion of the trapped bird in a glass case. Indeed, in describing his plays as ‘the result of observation and the study of life’,22 Chekhov’s description coheres with Sickert’s own ideas on painting: ‘[The painter] has all his work cut out for him, observing and recording. His poetry is the interpretation of everyday life.’23

A ‘slice of actual life’:24 Working class lives on the British stage

In addition to splintered relationships, the other key interest of the New Dramatist was the issue of class. Elizabeth Baker’s Chains (The Court for one performance on 18 April 1909 and the Duke of York’s 15 May–16 June 1910), for example, presents a similarly fractured duet to Ennui while highlighting the hardships faced by a lower class couple. Set in the sitting room of Charley and Lily Wilson, the play explores the drudgery of the life of a low-paid clerk. As Charley laments:

It’s that I’m just sick of the office and the grind every week and no change! – nothing new, nothing happening. Why, I haven’t seen anything of the world. I just settled down to it – why? – just because other chaps do, because it’s the right thing. I only live for Saturday.25

While no photographs of the production exist, Baker’s set description recalls several of Sickert’s interiors:

the principal articles of furniture are the centre table, set for dinner for three and a sideboard on the right ... Family photographs, a wedding group and a cricket group, and a big lithography copy of a Marcus Stone picture, are on the walls. There is a brass alarm clock on the mantelpiece and one or two ornaments ... A small vase of flowers stands in the centre of the dinner table.26

The play’s atmosphere similarly shared an affinity with Sickert’s paintings, especially Ennui, as the Stage noted: ‘there is hardly any action ... [it depicts the] poignant reality [of a] dull, commonplace existence in suburban West London’.27

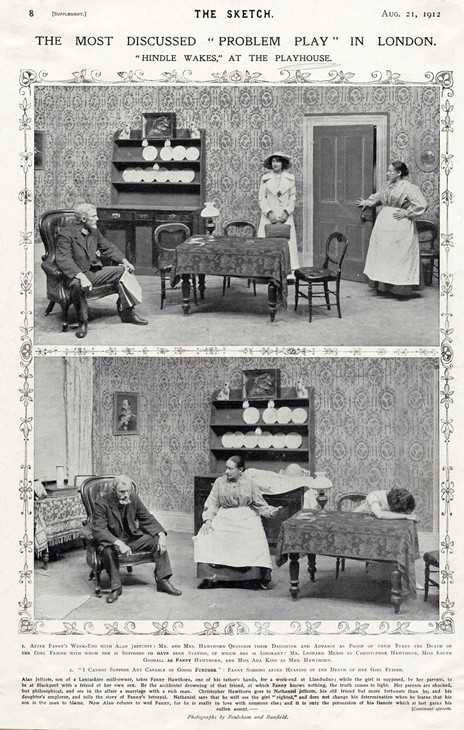

Leonard Mudie, Ada King and Fanny Goodall in Stanley Houghton's 'Hindle Wakes' 1912

Theatre and Performance Collections, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Theatre and Performance Collections

Fig.6

Leonard Mudie, Ada King and Fanny Goodall in Stanley Houghton's 'Hindle Wakes' 1912

Theatre and Performance Collections, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Theatre and Performance Collections

The Dormitory Scene in Cicely Hamilton's 'Diana of Dobson's' c.1908–9

Theatre and Performance Collections, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Theatre and Performance Collections

Fig.7

The Dormitory Scene in Cicely Hamilton's 'Diana of Dobson's' c.1908–9

Theatre and Performance Collections, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Theatre and Performance Collections

In the 1900s Galsworthy was the main advocate of the lower class on stage, but Stanley Houghton’s Hindle Wakes (Aldwych, Playhouse and Court theatres, 16 June–19 October 1912 and again at the Court, 22 September–18 October 1913, fig.6)28 and Cicely Hamilton’s Diana of Dobson’s (Kingsway Theatre, 12 February–20 June 1908 and 11 January–6 February 1909, fig.7) similarly drew upon working class characters and situations. Galsworthy’s The Silver Box (The Court, 25 September–19 October 1906 and 8–27 April 1907) highlights the inequality of justice between the classes, seen in this case through the aristocratic Barthwick and the lower class Jones families. Jack Barthwick, a young man about town, returns home drunk one evening and is helped inside by James Jones (the husband of the family’s maid). Jones takes advantage of Barthwick’s offer of thanks by seizing a silver cigarette box and a lady’s purse.29 The following morning the items are discovered missing and Mrs Jones is wrongly arrested for the crime. However, upon discovering that the lady’s purse was originally stolen by Jack, his father pays off the lady to avoid any scandal and only mildly reprimands his son. By contrast, after admitting his guilt Jones receives a month’s hard labour.

The Jones’s marriage is oppressive and violent: ‘Of course I would leave him, but I’m really afraid of what he’d do to me. He’s such a violent man when he’s not himself’, confesses Mrs Jones.30 The description of their lodging house reveals Galsworthy’s interest in a naturalistic set and recalls Sickert’s own compositions:

The Jones’ lodging, Merthyr Street, at half past two-o’clock. The bare room, with tattered oilcloth and damp, distempered walls, has an air of tidy wretchedness. On the bed lies Jones, half-dressed; his coat is thrown across his feet, and muddy boots are lying on the floor close by. He is asleep. The door is opened and Mrs Jones comes in, dressed in a pinched black jacket and old black sailor hat; she carries a parcel wrapped up in ‘The Times.’ She puts her parcel down, unwraps an apron, half a loaf, two onions, three potatoes, and a tiny piece of bacon. Taking a teapot from the cupboard, she rinses it, shakes into it some powdered tea out of a screw of paper, puts it on the hearth, and sitting in a wooden chair quietly begins to cry.31

The play, thought the Illustrated London News, was ‘full of careful observation and most of its types are wonderfully true to life’.32 It certainly shared some stylistic and thematic affinity with Sickert’s ideas on art, particularly a fascination with the secret and private lives of his domestic subjects:

But now let us strip Tilly Pullen of her lendings and tell her to put her own things on again. Let her leave the studio and climb the first dirty little staircase in her shabby little house. Tilly Pullen becomes interesting at once ... Follow her into the kitchen, or, better still ... into her bedroom, and now ... she has become a Degas or a Renoir.33

This concern with class is clearly manifested in Sickert’s Off to the Pub (fig.8), in which a lower class female figure, dressed in the costume of a coster-girl, sits in a drab and plainly furnished room. Her accomplice, probably her lover (and again Hubby, Sickert’s favoured model for scenes of this type), reaches for the door – suggesting his exit. Once more gestures and poses indicate some unsaid, unidentifiable disaffection in their relationship while simultaneously exploiting the lower class situation for dramatic effect.

In essence, Camden Town provided Sickert with a living stage-set, one filled with realist (in terms of subject matter and treatment) and naturalist (in terms of visuality) characters and sets. Contemporary theatre insisted on new styles and methods of performance and Sickert’s paintings reflect this ambition in their concentration on intimate, psychologically intense domestic duets. Filled as they are with modern figures and suggesting modern dilemmas, his images reveal his interest in the subtext of his ‘characters’; the implied hidden lives behind their situation. The accusations of depravity directed towards Sickert’s Camden Town works are perhaps not surprising. As the character, Paul, states in H.H. Davies’ play Lady Epping’s Lawsuit: ‘No one seems to think a play is serious unless it’s about unpleasant people.’34 Ultimately, the inspiration of the theatre on Sickert’s life and career was a powerful and instructive one, as he stated later in 1934: ‘The influence between brush and mask has at the best periods been reciprocal.’35

William Rough is a Teaching Fellow and School of Art History Evening Degree Coordinator at the University of St Andrews, Fife.

Notes

Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2000, p.241.

Jean Jullien, Le Théâtre vivant, G. Charpentier et E. Fasquelle, Paris 1892, pp.8–22. Originally written as a preface to his play L’Echéance (1890). As quoted in C. Schumacher (ed.), Naturalism and Symbolism in European Theatre 1850–1918, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1996, pp.77–8.

Era, 11 November 1905, p.17. Max Beerbohm thought the action in the second act particularly truthful: ‘In the second act we see the Voyseys in their daily round – in all the decent pettiness and dulness of their ordinary selves.’ Beerbohm, ‘The Voysey Inheritance’, Saturday Review, vol.100, no.2611, 11 November 1905, pp.620–1.

Jacques-Émile Blanche, Portraits of a Lifetime: 1870–1914, trans. and ed. by Walter Clements, introd. by Harley Granville-Barker, J.M. Dent & Sons, London 1938, p.227. Sickert’s friend, the painter William Rothenstein, was also a regular at the Court: ‘Like every other intelligent playgoer, William had been drawn to Granville-Barker’s productions at the Royal Court.’ Robert Speaight, William Rothenstein: The Portrait of an Artist in his Time, Eyre & Spottiswode, London 1962, p.223.

Ghosts starred Mrs Theodore Wright as Mrs Alving. In the 1920s Sickert produced a print entitled Mrs Theodore Wright as Mrs Alving (British Museum) which was certainly based on a sketch from either the 1891 or 1893 production. Reproduced in Ruth Bromberg, Walter Sickert Prints: A Catalogue Raisonné, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 2000, no.216.

Edith Craig, ‘First Annual Report. 1911–12’, The Pioneer Player Reports, 1911–1915, Ellen Terry Memorial Museum, Smallhythe, undated, p.7. Quoted in Susan Carlson and Kerry Powell, ‘Reimagining the Theatre: Women Playwrights of the Victorian and Edwardian Period’, in Kerry Powell (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Victorian and Edwardian Theatre, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2004, p.245.

Paston’s Nobody’s Daughter was performed at Wyndham’s Theatre, London (September 1910–February 1911). Fig.2 is from Playgoer and Society Illustrated, vol.5, no.27, December 1911, p.78 and fig.3 from Play Pictorial, vol.16, no.99, November 1910, p.133.

Reproduced in Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 2006, no.48.

For more on the Camden Town Group, see Wendy Baron, ‘The Domestic Theatre’, in Walter Sickert: ‘drawing is the thing’, exhibition catalogue, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester 2004, pp.6–10; Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, Scolar Press, London 1979; Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Ashgate, Aldershot 2000; Robert Upstone (ed.), Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2008; and Valerie Webb, The Camden Town Group: Representations of Class and Gender in Paintings of London Interiors, Parker Art Press, London 2007. For more on Ennui, see Ruth Bromberg, ‘Ennui: Etching as Drawing’, in Whitworth Art Gallery 2004, pp.15–16; Ruth Bromberg, Walter Sickert Prints: A Catalogue Raisonné, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 2000; Nicola Moorby, ‘“A long chapter from the ugly tale of commonplace living”: The Evolution of Sickert’s Ennui’, in Whitworth Art Gallery 2004, pp.11–14; Anna Gruetzner Robins, Walter Sickert: Drawings, Scolar Press, Aldershot 1996; Susan Sidlauskas, ‘Walter Sickert’s Ennui’, Body, Place, and Self in Nineteenth Century Painting, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2000, pp.124–49; and Stella Tillyard, ‘W.R. Sickert and the Defence of Illustrative Painting’, in Brian Allen (ed.), Studies in British Art 1: Towards a Modern Art World, Yale University Press, London 1995, pp.189–205.

Woolf 1934. For more on a possible literary reading of Sickert’s Camden Town works, see Richard Shone, ‘Text and Image: Camden Town Painting and Contemporary Fiction’, in Tate Britain 2008, pp.44–5, and Samuel Hynes, ‘Camden Town and its Literary Context’, Arts Magazine, vol.55, no.1, September 1980, pp.130–3.

George Bernard Shaw, ‘Getting Married’ (1905), in Dan H. Laurence (ed.), Bernard Shaw: Collected Plays with their Prefaces, vol.3, Bodley Head, London 1971, p.554. Sickert’s mocking nickname for Shaw was ‘George Bernard Cock-sure’. Matthew Sturgis, Walter Sickert: A Life, HarperCollins, London 2005, p.165.

Anton Chekhov, letter to Aleksey Suvorin, 30 December 1888. Quoted in Lillian Hellman (ed.), The Selected Letters of Anton Chekhov, Hamish Hamilton, New York 1955, p.77.

Walter Sickert, ‘The New Life of Whistler’, Fortnightly Review, December 1908, in Robins (ed.) 2000, p.185. The critic John Middleton Murry later stated: ‘Sickert has points of contact with the literary art and attitude of the Russian writer Tchehov. To some extent his Ennui is an English – a very English – counterpart of Tchehov’s Tedious Story.’ John Middleton Murry, ‘The Etchings of Walter Sickert’, Print Collector’s Quarterly, vol.10, 1923, p.54.

Illustrated London News on the 1906 production of John Galsworthy’s The Silver Box, vol.129, 6 October 1906, p.467.

Stage, 22 April 1909, p.9. The Era thought the first act, with the dialogue around the table between Charley, Lily and Fred, ‘the dullest and most unilluminating order [but completely] copied from life’, vol.72, 24 April 1909, p.19.

John Galsworthy, The Silver Box: The Plays of John Galsworthy, Duckworth, London 1929, Act I, Scene 2, p.5.

Ibid., Act II, Scene 1,p.21. Stage went so far as to mention that the action took place in the ‘Jones’s wretched furnished rooms (rent 6s a week)’, 27 September 1906, p.16. The links between Galsworthy and the developments in Paris were not lost on the critics: ‘One of the grimmest, most realistic, and most powerful studies of actual life ... seems to owe something to Scandinavian influence. ... The Court Theatre [is clearly] an equivalent of the Parisian Théâtre Antoine.’ Athenæum, no.4118, 29 September 1906, pp.375–6.

H.H. Davies, Lady Epping’s Lawsuit (1908), in The Plays of Hubert Henry Davies, Heinemann, London 1914, p.17.

How to cite

William Rough, ‘Walter Sickert and Contemporary Drama’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www