From Drawing Room to Scullery: Reading the Domestic Interior in the Paintings of Walter Sickert and the Camden Town Group

Juliet Kinchin

Whether set in a drawing room, bedroom or kitchen, Camden Town interior scenes reflected Edwardian society, its values and tastes. Focusing on the work of Walter Sickert, Juliet Kinchin explores the social meanings of domestic interiors in Camden Town paintings.

The tendency to judge developments in British art of the mid-nineteenth to early twentieth century in relation to a model of the French avant-garde has tended to obscure certain culturally specific qualities of British art and its domestic subject matter. Yet from Walter Sickert’s perspective it was clear that French and British art were building on different traditions:

The pictures at the New English Art Club are often described as impressionist, and their painters called impressionists. This always surprises and amuses French visitors to England. A painter is guided and pushed by his surroundings very much as an actor is, and the atmosphere of English society acting on a gifted group of painters, who had learned what they knew either in Paris or from Paris, has provided a school with aims and qualities altogether different from those of the impressionists.1

While the ‘gifted group of painters’ to whom Sickert refers were clearly indebted to French impressionism in terms of technique and composition, their different ‘aims and qualities’, he suggested, arose from a particular social and cultural context. This essay explores how Sickert and his Camden Town associates were ‘guided and pushed’ by their domestic surroundings to explore the shifting boundaries between psychological and corporeal space. Driving the content or narrative of many of their paintings was a nuanced understanding of symbolic, narrative and expressive conventions associated with the domestic landscape. This knowledge cut across ‘high’ and ‘low’ forms of visual, material and literary culture.

Sickert and his contemporaries were working within, and often against, an established British tradition of interior genre painting. The period was particularly rich in images of the home produced by amateur and professional artists for consumption in a variety of contexts, whether in the home itself, a gallery, department store, or on the pages of a popular magazine, theoretical treatise or government report. The level of interest in domestic interiors reflected the perceived centrality of the British home to wider debates about social and moral values, gender roles, the nation’s economy, as well as questions of taste, the function of art and its relationship with daily life. From the voluminous literature on household taste and interior decoration published in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and the repeated references to domestic design in numerous other sources, it is clear that specific rooms in the middle class home expressed a range of social and cultural meanings beyond any simple day-to-day use. The material culture of the home choreographed the interaction between people, objects and spaces, providing cues to particular forms of behaviour.

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Edwardian Interior c.1907

Oil paint on canvas

support: 533 x 540 mm

Tate T00096

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1956

Fig.1

Harold Gilman

Edwardian Interior c.1907

Tate T00096

In choosing to depict his youngest sister Irene against the backdrop of the drawing room in their parents’ home in Edwardian Interior, Gilman was exploring familiar territory. Since the mid-nineteenth century, the drawing room had been in the ascendant as the showpiece of the middle class home, as indicated by the proliferation of images painted by amateurs as well as professional artists like Atkinson Grimshaw.2 It was never an important space within working class or smaller rural homes, yet of all middle class room types it was the most heavily represented. Irene is firmly located in the interior, communing with her surroundings and subject to the visual control and aesthetic judgement of the onlooker. The tea table next to her, and by extension the interior replete with its ‘feminine’ signifiers – gilt-framed watercolours, oriental objets d’art, lacquer cabinet and profusion of soft furnishings – produce a space of contemplation and suspended animation.3

The processes of looking and being looked at were experienced with particular intensity in the drawing room, one of the most publicly visible and obviously theatrical spaces of the home where so many values and identities were contested.4 Women knew they were being observed here, and that their performances were crucial to social, and ultimately material success. This was particularly the case for unmarried women showcasing their artistry and accomplishments to prospective suitors. An awareness of being visible and endlessly observed was internalised into their self-conception. In this context all middle class women were in a sense actors, performing elaborate social rituals as ‘naturally’ as possible, without showing any signs of registering the analytical gaze of their audience. It was important to appear ‘at home’ and at one with the room in order to stress the consistency between one’s ‘true’ character and projected image.5

The drawing room often provided a setting for amateur dramatics, tableaux vivants, or ‘living pictures’ and musical soirées and, conversely, as Hugh Maguire has argued, the Victorian theatre was in many senses a ‘home from home’ that deployed a shared knowledge of furnishing conventions.6 In particular, creating tableaux vivants, drew attention to the artifice involved in women presenting themselves as art objects, and the impossibility of preserving vital, living beauty as part of an eternal harmony. A sense of boredom and almost deathly stillness comparable to that of a tableau vivant pervades an image like Gilman’s Edwardian Interior. This way of reading such pictures of women in interiors is made explicit in literary sources such as Edith Wharton’s novel The House of Mirth (1905) in which Lily Bart participates in a tableau vivant and consciously presents herself as an ‘art object’ in the drawing room.7

In contemporary literature on household taste, women were encouraged to see themselves as part of the drawing room scheme, and to match their figure, complexion and dress to the domestic environment. They were urged constantly to compose both themselves and their surroundings as a pictorial composition. According to Dr Jakob von Falke in 1879, this was ‘Woman’s Aesthetic Mission’:

As the mistress of the house she must accustom herself to look upon her rooms in all their details as pictures in which all things are so placed and so combined as to contribute to the general artistic effect ... no one object exists for itself alone, but in reference to all other objects.8

Interior settings became a frame delimiting the boundaries of a living artwork, which entailed matching the female figure, dress and complexion to the domestic environment:

Is she blond? Then let there be a modicum of pale blue within her bower ... rose will detract from a fair skin, pale turquoise would be preferable, but it will not suit a fresh complexion ... We prefer simple harmony here making the lady the concentration of the scheme.9

George Du Maurier 1834–1896

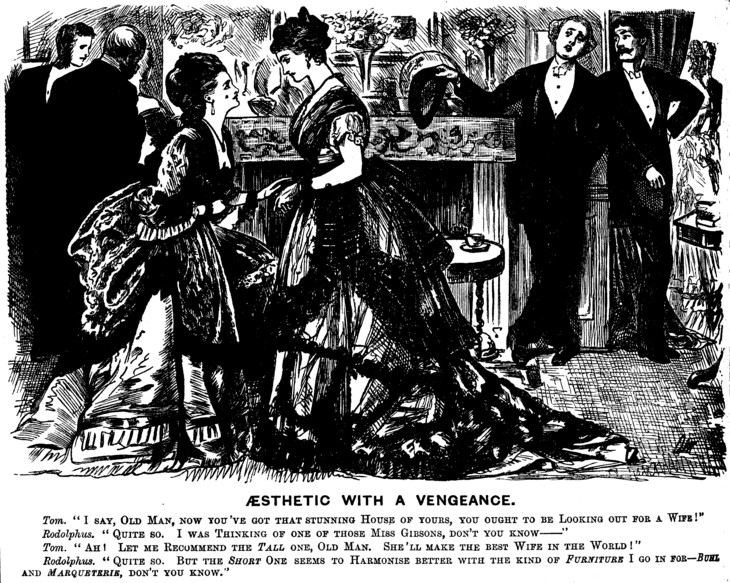

'Aesthetic with a Vengeance', Punch 8 March 1873

Photo © Juliet Kinchin

Fig.2

George Du Maurier

'Aesthetic with a Vengeance', Punch 8 March 1873

Photo © Juliet Kinchin

Ethel Sands 1873–1962

The Chintz Couch c.1910–11

Oil paint on board

support: 465 x 385 mm

Tate N03845

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1924

© The estate of Ethel Sands

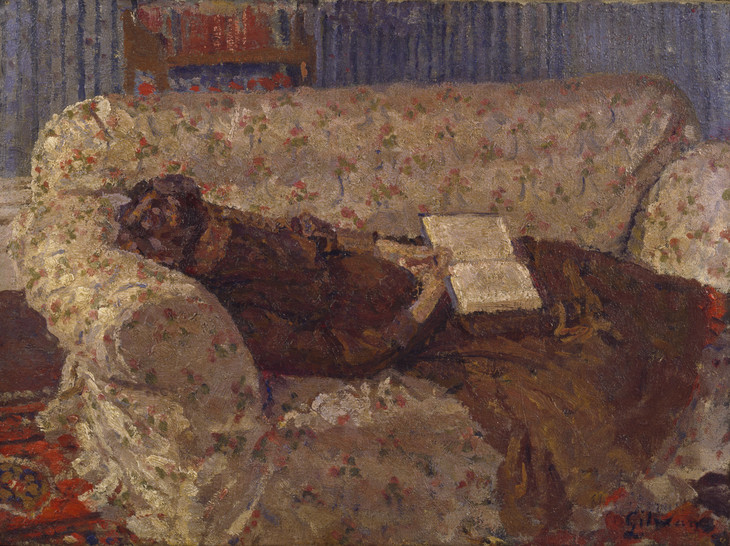

Fig.3

Ethel Sands

The Chintz Couch c.1910–11

Tate N03845

© The estate of Ethel Sands

The cartoons of George du Maurier in Punch magazine, addressed to a knowing audience, parodied feminine beauty as an artistic commodity interchangeable with the furnishings of the drawing room. ‘Aesthetic with a vengeance’, for example, depicts a bachelor who owns a ‘stunning house’ eying up two sisters as potential marriage material at a drawing room soirée (fig.2). On the basis of looks he plumps for the short one on the grounds that she ‘seems to harmonise better with the kind of furniture I go in for – buhl and marqueterie, don’t you know’.10 The conceptual conflation of women with their interiors, in particular soft furnishings and flower arrangements, is similarly marked in The Chintz Couch c.1910–11, by Ethel Sands (Tate N03845, fig.3). Despite her physical absence from this London drawing room in fashionable Belgravia, the interior reads as a self-portrait, saturated with the aesthetic sensibility of the artist as both a woman and an interior decorator.11

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Lady on a Sofa c.1910

Oil paint on canvas

support: 305 x 406 mm; frame: 475 x 578 x 100 mm

Tate N05831

Purchased 1948

Fig.4

Harold Gilman

Lady on a Sofa c.1910

Tate N05831

Philip Wilson Steer 1860–1942

Girl on a Sofa 1891

Oil paint on canvas

563 x 613 mm

Colchester and Ipswich Museum Service

© Estate of Philip Wilson Steer

Photo © Colchester and Ipswich Museum Service

Fig.5

Philip Wilson Steer

Girl on a Sofa 1891

Colchester and Ipswich Museum Service

© Estate of Philip Wilson Steer

Photo © Colchester and Ipswich Museum Service

Harold Gilman’s Lady on a Sofa, c.1910 (Tate N05831, fig.4), deploys another familiar trope, that of the recumbent, novel-reading woman in the drawing room (fig.5).12 Novels and poetry were considered suitably lightweight or ‘imaginative’ reading matter for those interiors in which women might pass their ‘idle’ hours, and most drawing rooms were equipped with reading lamps and appropriately small or mobile bookcases. Not only were the narratives of many bourgeois domestic dramas unfolded in the context of the drawing room, this was also where avid novel readers could consume and internalise the details of such literary descriptions in situ. The book being read by the model in Gilman’s picture becomes an oneiric medium for the displaced fantasies and recollections of the spectator, and this private introverted moment has a voyeuristic appeal.

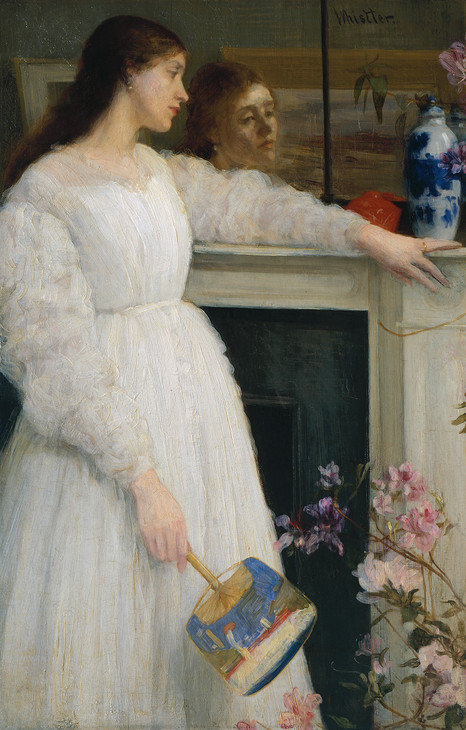

A similar sense of voyeurism and interiority characterises Sickert’s The Mantelpiece c.1906–7 (fig.6). This painting takes its cue from earlier images of women looking into mirrors, in particular paintings by Sickert’s one-time mentor, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, such as Symphony in White, No.2: The Little White Girl 1864 (Tate N03418, fig.7). In the latter, Whistler seamlessly relates the poised female subject-object with the idealised environment of his drawing room in Lindsay Row. In effect, the autonomy of the female figure is dissolved into an image that the title likens to the musical performance of a ‘symphony’.13

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Mantelpiece c.1906–7

Oil paint on canvas

762 x 508 mm

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.6

Walter Richard Sickert

The Mantelpiece c.1906–7

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

James Abbott McNeill Whistler 1834–1903

Symphony in White, No. 2: The Little White Girl 1864

Oil on canvas

support: 765 x 511 mm; frame: 1085 x 830 x 118 mm

Tate N03418

Bequeathed by Arthur Studd 1919

Fig.7

James Abbott McNeill Whistler

Symphony in White, No. 2: The Little White Girl 1864

Tate N03418

Mirrors dominated many late Victorian and Edwardian drawing room schemes, objectifying notions of surveillance and reinforcing the self-regulation of behaviour. The representational trope of the watched woman watching herself before the mirror was elaborated in countless novels, paintings and photographs of the period.14 In painting the model’s reflected image, Whistler freezes for eternity a momentary experience that would otherwise exist only as a fleeting memory or fantasy, an element of the interior that could be seen but not touched. The woman’s psychological interior and her physical self, along with the reflected and actual spaces of the interior, converge onto the same flattened plane of the canvas. She can be read as a composite held together by artifice, like the interior and the painting itself.

Whistler is generally regarded as an innovator in his approach to the domestic interior, not only as an artist, but also as a collector and interior decorator. The artist’s house was a new phenomenon of the late nineteenth century, widely discussed and illustrated in the art press as an emanation of the individual artist’s persona.15 In other words, for Whistler the drawing room was not only a rich vein of subject matter, it provided the whole context within which such paintings were produced, displayed and consumed. The artist’s house was also the context in which Aesthetic paintings were sold to private clients and by dealers like Augustus Howell.

By 1908, however, Sickert had become openly critical of Whistler, penning the first of several damning articles that caricatured the unspoken cultural values and outmoded social and aesthetic conventions for which his one-time mentor now stood:

Suppose we get the loveliest woman procurable, and put her in the finest robe imaginable! Suppose we even design the dress! ... Let us surround her with the most precious china! Let there be sprays of azalea, and so on! Perhaps we shall thus create a very Paradise of art! Who knows? Ought not the product to be a very syrup of the purest taste?16

Not as far as Sickert was concerned; ‘the lilies and languors of the Chelsea amateurs’ had sent Whistler into the cul-de-sac of the drawing room and stifled him there. ‘Taste’ was the death of a painter; it got in the way of observing and recording ‘ready-made life’.17 His own painting of that year, The New Home, features a working class woman seated by the fireplace of her ‘sordid’ lodgings in Camden Town, rather than ‘the loveliest woman procurable’ in a bourgeois drawing room (fig.8).18 Here the old-fashioned bell jar, white fire surround and dingy wallpaper stand in deliberate contrast to Whistler’s ‘syrup of taste’, as do the bearing and dress of the model, one of two coster-girls whom Sickert described to his friends Ethel Sands and Nan Hudson as clad ‘in the sumptuous poverty of their class, sham velvet etc.’19

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The New Home 1908

Oil paint on canvas

495 x 390 mm

Private collection, Ivor Braka Ltd

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Ivor Braka Ltd, London

Fig.8

Walter Richard Sickert

The New Home 1908

Private collection, Ivor Braka Ltd

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Ivor Braka Ltd, London

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table exhibited 1917

Oil paint on canvas

support: 610 x 406 mm; frame: 808 x 605 x 93 mm

Tate N05317

Purchased 1942

Fig.9

Harold Gilman

Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table exhibited 1917

Tate N05317

Sickert deliberately challenges the narcissistic spell of the reflected image, and exposes the paradox of cultivating ‘natural’ behaviour in an inherently artificial environment. There is an apparent disjuncture between the woman’s dress, environment and state of mind. Her uncomfortable body language sends out messages which conflict with the concept of home as restorative or as the ‘outermost garment of a woman’s soul’.20 The fact that she is still wearing her hat suggests she is a visitor rather than ‘at home’ in her private space. Gilman’s portrait of Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table exhibited 1917 (Tate N05317, fig.9), can be read as a critique in a similar vein – in this case the ‘loveliest woman procurable’ was his aging house-keeper, wearing an unfashionable headscarf far from ‘the finest robe imaginable’, and sitting behind a plain earthenware teapot and non-matching cups rather than ‘the most precious china’. Unlike Whistler’s ‘Little White Girl’ or Gilman’s sister Irene, Mrs Mounter returns the onlooker’s gaze directly. She is no objectified, passive cipher for the sphere of poetic and spiritual values, but an individual whose face shows the traces of aging and lived experience.

Sickert continued his critique of Whistler in 1910: ‘The more our art is serious, the more will it tend to avoid the drawing-room and stick to the kitchen ... Stay! I had forgot,’ he continued, ‘We have a use for the drawing-room – to caricature it.’21 Such comments were hardly radical. There was widespread criticism of the drawing room as the setting for superficial socialising and meaningless pretension, the antithesis of ‘serious’ culture. In his penetrating account of The English House published in 1904, for example, the German art critic Hermann Muthesius described the decoration and content of the drawing room as precluding ‘seriousness’. ‘The trend throughout is towards prettiness, casualness and lightness,’ he continued, ‘a feminine characteristic.’

Such comments exemplify a chain of associative thinking that drew drawing rooms into the negative discourse surrounding women, consumerism and fashion. Since John Ruskin’s critique of the veneered drawing room furniture in William Holman Hunt’s Awakening Conscience of 1853 and the publication of Charles Locke Eastlake’s popular Hints on Household Taste in 1868, the reflective surfaces of the drawing room had been vilified constantly in the literature on household taste as vulgar, ostentatious and deceptive, and in terms that communicated an underlying anxiety about a collapse of distinctions between counterfeit and genuine, person and thing.22 Sickert picked up this rhetoric:

The plastic arts are gross arts, dealing joyously with gross material facts. They call, in their servants, for a robust stomach and a great power of endurance, and while they will flourish in the scullery, or on the dunghill, they fade at a breath from the drawing-room.23

Sickert’s ‘gross arts’ make reference to touch (‘plastic’), taste (‘robust stomach’) and smell (‘dunghill’), as compared to the scent of azaleas, the sweet and smooth taste of syrup, and the refined tactility of china and textiles in Whistler’s art. This contrasted register of sensory detail is carried through into Sickert’s depictions of domestic space in the years that followed. The dung-coloured dinginess of his Camden Town interiors resists co-option into Whistler’s hyper-refined aesthetic. Within the home generally, and the drawing room in particular, women were expected to create an oasis of light and calm. Furnishings that were light in colour and form could provide a material analogy for the hygienic and spiritual purity of the household, an analogy undermined by Sickert. The aura of grime and excrement conveyed in his Camden Town works, redolent of bodily needs and mortality, marks the return of the repressed – all those elements that Whistler’s aestheticism had sought to suppress and sublimate. Although the image of the dunghill alluded to decay and putrefaction, however, it also held within it the promise of fertilised, organic growth, and a more vital connection between life and art than the Aesthetes could offer.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Ennui c.1914

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1524 x 1124 mm; frame: 1741 x 1340 x 110 mm

Tate N03846

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1924

© Tate

Fig.10

Walter Richard Sickert

Ennui c.1914

Tate N03846

© Tate

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Little Tea Party: Nina Hamnett and Roald Kristian 1915–16

Oil paint on canvas

support: 254 x 356 mm; frame: 421 x 513 x 88 mm

Tate N05288

Purchased 1941

© Tate

Fig.11

Walter Richard Sickert

The Little Tea Party: Nina Hamnett and Roald Kristian 1915–16

Tate N05288

© Tate

Sickert’s most famous picture, Ennui (Tate N03846, fig.10), was elaborated from preparatory drawings into five versions, the largest of which was exhibited at the 1914 New English Art Club show. It brings the viewer closer to a messy, lived domestic experience than Whistler’s Symphony in White No.2, despite the ambiguity of the apparent ‘realism’ and the equally staged nature of the scene. The setting was a room in Granby Street in London’s Camden Town, which Sickert had used as a studio from around 1908. Unlike Whistler, he kept his home and work life separate. ‘There is a constant snare in painting what is part of your life’, he warned two of his pupils.24 The alcoholic ‘Hubby’ and Marie Hayes, who had joined his unconventional household, served as models. As in The Little Tea Party: Nina Hamnett and Roald Kristian of 1915–16 (Tate N05288, fig.11), the implicit sociability of the bourgeois drawing room is critiqued in the dislocated positioning of the two figures, each locked into a private reverie, their body language acting out the effects of alienation and psychological discomfort. The bored stance of the woman propped against the chest of drawers and the man’s gaze into the middle distance through a haze of smoke and alcohol, is suggestive of claustrophobia and enervation.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

My Awful Dad c.1912

Chalk on paper

248 x 347 mm

The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

Fig.12

Walter Richard Sickert

My Awful Dad c.1912

The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

Containing dried flowers and stuffed birds, the glass bell jar in Ennui is old-fashioned, a symbol of petrified life in which time and space are compressed. (It had already appeared in The Mantelpiece c.1906–7 and The New Home 1908.) It represents a miniaturised world, a mnemonic universe within the already self-contained environment of the interior, its contents guarded from external intrusion by the glass, to be looked at but not touched. The prominence of the bell jar parodies the correlation of ‘taste’ and artistic discrimination with collecting interests focused on exquisite and rare or curious items in the conventional drawing room; such items were designed to stimulate the imagination and refined conversation, providing an informal education through the emanation of moral sentiment, history and cosmopolitan culture.

In Ennui, however, the implied journey of the woman’s imagination does not take us to far-off cultures and places, but into this tiny mortuary of organic life. The glass dome represents an attempt to collect organic and authentic experience of the ‘natural world’ within the confines of the domestic interior, but paradoxically its contents – no longer connected to anything vital – have become emblems of death, boredom and unrepeatable experience. Like the mantel mirror in Symphony in White No. 2, the bell jar acts as a framing device or container of lived experience that can exist only at the level of memory or fantasy. Just as the domed glass encases its specimens, so Whistler’s drawing room (and Gilman’s Edwardian Interior) entrap the woman as a decorative object to be ogled at and visually possessed, as if in a fish bowl. Life outside the bell jar in Sickert’s studio might confront the viewer with signs of mortality and decay, but at least it is vital. The theme of ‘vital’ decay and visual containment behind glass was further developed in the small still life, Roquefort, painted after the First World War at his French home in Envermeu (Tate N03847, fig.13). The image of the cheese evokes a pungent sense of smell combined with a sensual, life-affirming pleasure in plain food and beer that indirectly debunks the stilted British emulation of French ‘taste’.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Roquefort c.1919–20

Oil paint on canvas

support: 409 x 328 mm

Tate N03847

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1924

© Tate

Fig.13

Walter Richard Sickert

Roquefort c.1919–20

Tate N03847

© Tate

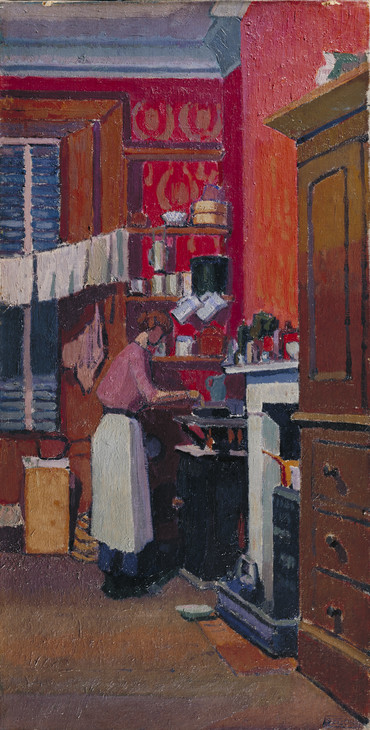

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

The Gas Cooker 1913

Oil paint on canvas

support: 730 x 368 mm; frame: 898 x 556 x 63 mm

Tate T00496

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1962

Fig.14

Spencer Gore

The Gas Cooker 1913

Tate T00496

In The Gas Cooker 1913 (fig.14), Spencer Gore followed Sickert’s injunction to privilege the scullery over the drawing room, while also exploiting the transient coding of interiors and his audience’s ability to read a mismatch between interior environs and the social class of occupants. The painting shows his wife Mollie cooking in the first-floor flat they occupied at 2 Houghton Place NW1. The height of the room and red décor of the walls are a residue of the former grandeur of what must have been one of the main public rooms when the property functioned as a town house spread over five floors. A string of washing hangs across the window rather than muslin curtains; there is no hearth rug, and the floor covering appears plain and durable, as one would expect to find in service quarters. Foodstuffs and an assortment of kitchen equipment crowd along the mantelpiece rather than a tasteful, symmetrically arranged garniture to either side of a mantel clock.

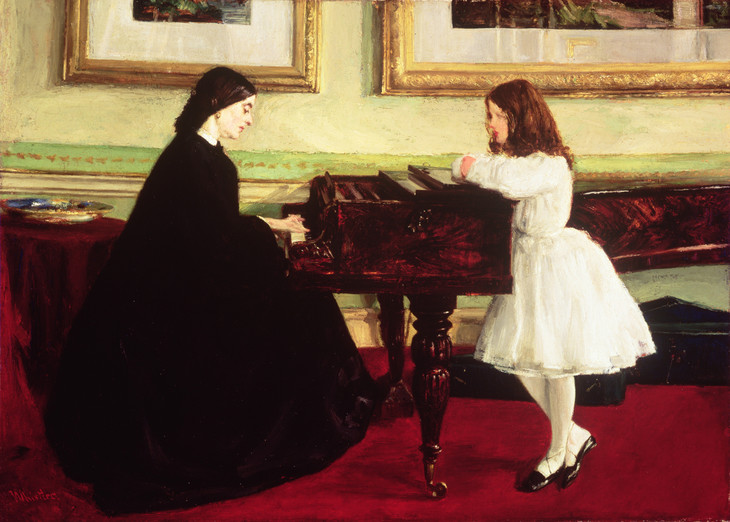

As a professional actor and flamboyant character himself, Sickert understood the nature of theatrical performance. ‘The house, where man is born, and married, and dies, becomes his theatre’, he wrote in 1914.25 In particular he revelled in the transparently artificial and jingoistic art form of the music hall that had no pretensions to being ‘high art’.26 The painting he exhibited at the New English Art Club in 1888, Gatti’s Hungerford Palace of Varieties, caused a storm of controversy. The Artist said that it embodied ‘the aggressive squalor which pervades to a greater or lesser extent the whole of modern existence’.27 By means of a title, Tipperary (referring to the popular music hall song), he later transferred a hint of this ‘squalor’ into the domestic environment with an image of his gawky, toothy model (Emily Powell, known as ‘Chicken’) rattling out the rousing tune on a grand piano (Tate N05092, fig.15).28 The raucous sounds of this domestic concert serve to rupture the ‘naturalised’ performances associated both with the classic theatre and with the bourgeois home, critiquing images of music-making in the drawing room that extended back to Whistler’s At the Piano 1858–9 (fig.16). Equally damning was his view of the supposedly genteel interaction of the tea party, another ritual closely linked to the drawing room, in his painting The Little Tea Party (fig.11).

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Tipperary 1914

Oil paint on canvas

support: 508 x 406 mm; frame: 600 x 500 x 55 mm

Tate N05092

Bequeathed by Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck 1940

© Tate

Fig.15

Walter Richard Sickert

Tipperary 1914

Tate N05092

© Tate

James Abbott McNeill Whistler 1834–1903

At the Piano 1858–9

Oil paint on canvas

665 x 915 mm

Taft Museum of Art. Bequest of Louise Taft Semple

Photo © Taft Museum of Art, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.16

James Abbott McNeill Whistler

At the Piano 1858–9

Taft Museum of Art. Bequest of Louise Taft Semple

Photo © Taft Museum of Art, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA / The Bridgeman Art Library

Of all the Camden Town artists, arguably it was Sickert who provided the most sophisticated and damning critique of the contemporary vogue for depicting domestic spaces, but Gilman and Gore also exhibited a new understanding of the social and psychological dimensions of such subject matter and contributed to the complex discourse surrounding ‘artistic’ taste and domestic interiors in Britain that had been ongoing since the 1860s. In attempting a more ‘authentic’ record of interiors in their own and their families’ houses, they gradually distanced themselves from the idea of artists’ houses as the epitome of fashionable, middle class taste in the Anglo-American world. While the type of domestic interiors might have changed, the resonance of such images continued to draw on a distinctively British and deeply embedded tradition of design and representation that distinguished the Camden Town paintings from comparable works by French avant-garde artists.

Notes

Italics added. Walter Sickert, ‘The New English and After’, New Age, 2 June 1910, pp.109–10, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2000, p.241.

See, for example, Grimshaw’s paintings Dulce Domum 1876–85 (private collection) and The Cradle Song 1878 (private collection).

On the gendering of nineteenth-century interiors, see Juliet Kinchin, ‘Interiors: Nineteenth-Century Essays on the “Masculine” and the “Feminine” Room’, in Pat Kirkham (ed.), The Gendered Object, Manchester University Press, Manchester 1996, pp.12–29.

See Juliet Kinchin, ‘Performance and the Reflected Self: Three Stagings in Domestic Space’, Studies in the Decorative Arts, vol.16, no.1, Fall–Winter 2008–9, pp.64–91; Thad Logan, The Victorian Parlour, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2001; Juliet Kinchin, ‘The Drawing Room’, in Annette Carruthers (ed.), The Scottish Home, National Museums of Scotland, Edinburgh 1996, pp.155–80.

This theme emerges strongly in novels like Margaret Oliphant, Miss Marjoribanks, W. Blackwood & Sons, London 1866, and Catherine Carswell, Open the Door!, Andrew Melrose Ltd, London 1920. See Kinchin 1996, pp.12–29.

Hugh Maguire, ‘The Victorian Theatre as a Home from Home’, Journal of Design History, vol.13, no.2, 2000, pp.107–21.

Jakob von Falke, Art in the House, L. Prang & Co., Boston 1879, p.333. There were also editions in Britain and Austria. The most popular late nineteenth-century texts often had American and English editions, and were readily available both sides of the Atlantic. There is a slight change in emphasis in the 1870s to 1910, but tropes like the one identified here remain remarkably consistent.

Owen Davis, Instruction for the Adornment of Dwelling Houses: Interior Decoration, Winsor and Newton, London 1880, p.25. A copy of this book is held in the Mitchell Library, Glasgow, D270304.

Nicola Moorby, ‘Her Indoors: Women Artists and Depictions of the Domestic Interior’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.),The Camden Town Group in Context, May 2012, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/nicola-moorby-her-indoors-women-artists-and-depictions-of-the-domestic-interior-r1104359 , accessed 27 August 2013.

See, for example, Julie Lawson, Women in White: Photographs by Lady Hawarden, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh 1997, and Margaret Oliphant, Miss Marjoribanks, Virago, London 1988, p.67.

There is an extensive primary and secondary literature on the phenomenon of artists’ houses. See, for example, Giles Walkley, Artists’ Houses in London 1764–1914, Scolar Press, Aldershot 1994.

Walter Sickert, ‘The New Life of Whistler’, Fortnightly Review, December 1908, p.84, in Robins (ed.) 2000, p.184.

The critic of the Pall Mall Gazette wrote, ‘Here is a young woman ill at ease ... taking very unkindly to the second-rate, sordid lodging, to which she is condemned by an unkindly Fate’ (3 June 1908).

Walter Sickert, letter to Ethel Sands and Nan Hudson, 1907; quoted in Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, Yale University Press, New Haven 2006, p.73.

‘The Final Causes of Women’, in J. Butler (ed.), Woman’s Work and Woman’s Culture, London 1869, pp.10–11.

Quoted in Richard Shone, ‘Walter Sickert, the Dispassionate Observer’, in Wendy Baron and Richard Shone (eds.), Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992, p.4.

Anna Gruetzner Robins, ‘Sickert “Painter-in-Ordinary” to the Music-Hall’, in Royal Academy 1992, pp.13–24.

Acknowledgments

The content of this essay was developed in collaboration with Dr Paul Stirton (The Bard Graduate Center for Studies in Design, New York).

The content of this essay was developed in collaboration with Dr Paul Stirton (The Bard Graduate Center for Studies in Design, New York).

Juliet Kinchin is Curator in the Department of Architecture and Design at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, and an Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the University of Glasgow.

How to cite

Juliet Kinchin, ‘From Drawing Room to Scullery: Reading the Domestic Interior in the Paintings of Walter Sickert and the Camden Town Group’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www