Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Joseph Mallord William Turner was born, it is thought, on 23 April 1775 at 21 Maiden Lane, Covent Garden, London, the son of William Turner (1745–1829), a barber and wig-maker, and his wife Mary, née Marshall (1739–1804). His father, born in South Molton, Devon, had moved to London around 1770 to follow his own father’s trade. His mother came from a line of prosperous London butchers and shopkeepers. Joseph Mallord William Turner was baptised at the local church, St Paul’s in Covent Garden, on 14 May. A sister, Mary Anne, was born in 1778 but died in 1783, just before her fifth birthday. In 1796 the family moved to 26 Hand Court, on the other side of Maiden Lane (fig.2). Turner remained a Londoner and kept a Cockney accent all his life, avoiding the veneer of social polish acquired by many artists of the time as they climbed the professional ladder.

John Wykeham Archer

J.M.W. Turner's birthplace in Maiden Lane, Covent Garden 1852

355 x 222 mm

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.2

John Wykeham Archer

J.M.W. Turner's birthplace in Maiden Lane, Covent Garden 1852

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Turner’s varied activities indicate wide interests as well as a need to fund his Academy education. The flourishing market for landscape and antiquarian topography, whether watercolours for exhibition and sale or reproduction in prints and books, provided his first real income. Early trips outside London, including a visit to friends of his father’s at Bristol in 1791, alerted him to the value of sketching on the spot as the basis of studio and commercial work; he seems to have thought of having his views of the Avon Gorge – which won him the nickname ‘Prince of the Rocks’ – published as prints (fig.3). From the mid-1790s he settled on the routine he maintained for much of his life: touring in summer and working in the studio in the winter months, for the following year’s exhibitions, on commissions or for the engraver. The first engravings after his topographical drawings appeared in the Copper-Plate Magazine (1794–8) and the Pocket Magazine (1795–6). Post-revolutionary wars in Europe confined his first tours to home ground; the Midlands in 1794, the North in 1797 and Wales on several occasions up to 1799. In 1801 he visited Scotland.

Turner exhibited at the Royal Academy from 1790, showing watercolours until 1796 when he sent his first oil, Fishermen at Sea (Tate T01585, fig.4), its marine subject signalling wider ambitions as a painter and his refusal to be typecast as a topographer. In the following years his exhibited works diversified into history, literature and myth, challenged the styles of the Old Masters and made rapid advances in technique. While some of his first important commissions were for architectural and topographical watercolours such as views of Salisbury and its cathedral and his country estate, Stourhead, ordered by Richard Colt Hoare in 1795, prominent patrons soon supported his wider endeavours. William Beckford commissioned views of his new Gothic palace, Fonthill, but also bought Turner’s first history painting The Fifth Plague of Egypt (Indianapolis Museum of Art), an essay in the manner of the French painter Nicolas Poussin, in 1800. The same year, the Duke of Bridgewater commissioned Dutch Boats in a Gale (private collection) as a companion for his Rising Gale by Willem van de Velde the younger (Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio). In 1802, during the Peace of Amiens, a consortium of noblemen sponsored a visit to Paris, enabling Turner to study the Old Masters in the Louvre, and a tour of the Swiss Alps. Newbey Lowson, a gentleman from County Durham, travelled with Turner as paymaster, providing a French-speaking guide and a small coach (fig.5).

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Fishermen at Sea exhibited 1796

Oil paint on canvas

support: 914 x 1222 mm; frame: 1120 x 1425 x 105 mm

Tate T01585

Purchased 1972

Fig.4

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Fishermen at Sea exhibited 1796

Tate T01585

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

The Post House, Voreppe with the Grand Aiguille Beyond, with Turner's Cabriolet 1802

Gouache and graphite on paper

support: 219 x 253 mm

Tate D04515

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.5

Joseph Mallord William Turner

The Post House, Voreppe with the Grand Aiguille Beyond, with Turner's Cabriolet 1802

Tate D04515

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Petworth, Sussex, the Seat of the Earl of Egremont: Dewy Morning exhibited 1810

Oil paint on canvas

support: 915 x 1205 mm; frame: 1267 x 1565 x 178 mm

Tate T03880

Accepted by HM Government in lieu of tax and allocated to the Tate Gallery 1984. In situ at Petworth House

Fig.6

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Petworth, Sussex, the Seat of the Earl of Egremont: Dewy Morning exhibited 1810

Tate T03880

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Tabley, Cheshire, the Seat of Sir J.F. Leicester, Bart.: Calm Morning exhibited 1809

Oil paint on canvas

support: 910 x 1215 mm; frame: 1264 x 1573 x 170 mm

Tate T03878

Accepted by HM Government in lieu of tax and allocated to the Tate Gallery 1984. In situ at Petworth House

Fig.7

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Tabley, Cheshire, the Seat of Sir J.F. Leicester, Bart.: Calm Morning exhibited 1809

Tate T03878

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Lecture Diagram 26: Interior of the Great Room at Somerset House, London circa 1810

Graphite and watercolour on paper

support: 669 x 1000 mm

Tate D17040

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.8

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Lecture Diagram 26: Interior of the Great Room at Somerset House, London circa 1810

Tate D17040

The lectures and the Liber showed Turner at his most didactic, and with his gallery and other exhibited works demonstrated his extraordinary energy and determination to command the public sphere. All this excluded much in the way of a private life and such as he had was closely tied to his work, although it revealed a contrary need for seclusion which, in later years, mutated into secrecy or deliberate mystification. From Thames-side lodgings at Sion (Syon) Ferry House, Isleworth, 1805–6 (fig.9) and Upper Mall, Hammersmith, 1806–11, he explored the river and pursued his favourite hobby, fishing – characteristically, a solitary one. Sketches of the Thames in watercolour and oil exemplify the naturalism then emerging in British painting. Others transform it into an antique land, inspired by Claude’s classical seaports and the Greek and Roman literature that Turner’s friend Henry Scott Trimmer, a clergyman and classicist, was trying to teach him to read. Acutely conscious of the cultural history of the Thames riverside, the former home of poets and painters, Turner was disgusted at the demolition by a philistine baroness in 1807 of Alexander Pope’s famous villa at Twickenham – the subject of a picture and anguished outpourings of verse. In 1807 Turner bought his own plot at Twickenham where he designed and built a villa, Sandycombe (sometimes ‘Solus’) Lodge (fig.10). In retreat there he was looked after by his devoted father, who cooked and gardened. His mother had died in 1804, probably at Bethlem, and he had not married, once remarking in a sketchbook that ‘Woman is doubtful love’. For a few years he had been close to Sarah Danby, the widow of a well-known musician but, inevitably, they were often apart. She bore two daughters, Evelina and Georgiana, who have been widely recognised as Turner’s, although a recent theory suggests that they were his father’s, and thus his half-sisters. Hannah Danby, niece of Sarah’s late husband, was Turner’s housekeeper at Queen Anne Street until his death.

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Sion Ferry House, Isleworth: Sunset 1805

Graphite and watercolour on paper

support: 260 x 369 mm

Tate D05952

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.9

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Sion Ferry House, Isleworth: Sunset 1805

Tate D05952

William Havell 1782–1857

Sandycombe Lodge, Twickenham, Villa of J.M.W. Turner, engraved by W.B. Cooke published 1814

Engraving on paper

Tate T06433

Transferred from the British Museum 1988

Fig.10

William Havell

Sandycombe Lodge, Twickenham, Villa of J.M.W. Turner, engraved by W.B. Cooke published 1814

Tate T06433

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Crossing the Brook exhibited 1815

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1930 x 1651 mm; frame: 2060 x 2350 x 180 mm

Tate N00497

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.11

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Crossing the Brook exhibited 1815

Tate N00497

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

The Field of Waterloo exhibited 1818

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1473 x 2388 mm

Tate N00500

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.12

Joseph Mallord William Turner

The Field of Waterloo exhibited 1818

Tate N00500

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

The Decline of the Carthaginian Empire ... exhibited 1817

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1702 x 2388 mm; frame: 2150 x 2840 x 200mm

Tate N00499

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.13

Joseph Mallord William Turner

The Decline of the Carthaginian Empire ... exhibited 1817

Tate N00499

George Jones

Interior of Turner's Gallery: the Artist showing his Works c.1851

Oil on millboard

1400 x 2300 mm

Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Fig.14

George Jones

Interior of Turner's Gallery: the Artist showing his Works c.1851

Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

In 1819 and 1828, Turner visited Italy. The first time he travelled to Venice, Rome and Naples but on his second visit based himself in Rome, where he painted and exhibited new works; his bright colouring and impromptu handling bemused German artists, who expected more finish. In the intervening years Turner continued his routine of touring, painting and working for publishers at home and on the continent. On successive visits to France he explored the Loire in 1826 and Seine from 1821–32. A larger plan to portray the great rivers of Europe was never realised, but three volumes of prints were published by Heath with letterpress by Leitch Ritchie as Wandering by the Loire and Seine (1833–5). Marketed as ‘Turner’s Annual Tour’ and later combined as Rivers of France,they were pitched at new middle class readers who might expect to follow in the artist’s footsteps. Meanwhile, in 1818 Turner had opened a seam of overtly literary topography, visiting Scotland to illustrate Walter Scott’s Picturesque Antiquities. Illustrations to Scott’s poetry, novels and Life of Napoleon, Byron, the banker-poet Samuel Rogers, Thomas Campbell and Thomas Moore as well as John Milton and the Bible, often designed as vignettes – a form Turner made very much his own – followed in the coming years. Among living poets, Turner was fondest of Byron’s writing, borrowing more passages from Childe Harold as themes for pictures, but he knew Rogers and Scott best. With other luminaries of literary and artistic London, he was pictured among the guests who frequented Rogers’s celebrated breakfast-parties in St James’s (fig.15). He visited Scott at Abbotsford, and Scott’s role as stage-manager of George IV’s visit to Edinburgh in 1822 was a factor in his attempt at a set of paintings recording the royal progress. These were left unfinished but in 1823 Turner finally obtained a longed-for royal commission, an immense picture of the Battle of Trafalgar (National Maritime Museum, Greenwich).

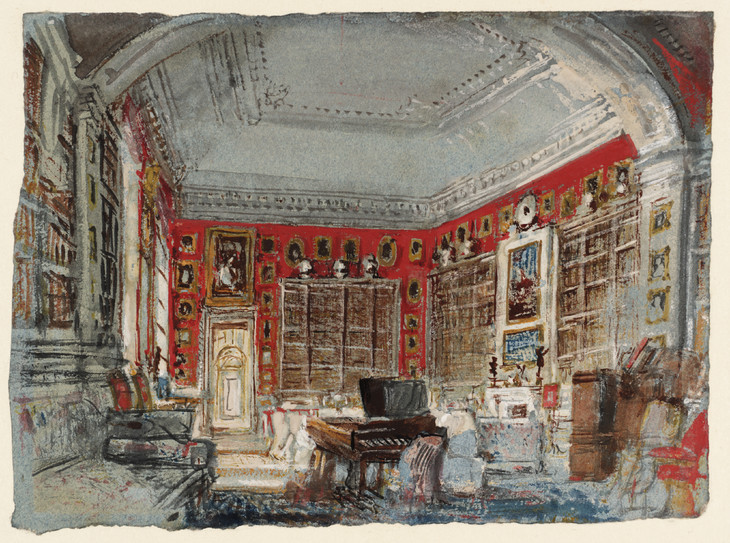

In 1825 Fawkes died. Turner never revisited Farnley but, in the decade until Egremont’s death in 1837, he had the run of Petworth where he used the Old Library as a studio. From contemporary accounts and on the evidence of Turner’s many drawings (figs.16 and 17) it was a special place, its treasures and varied company at his behest. Egremont’s unconventional household of rival mistresses, swarms of children and visiting artists would in due course arouse Victorian censure but gave Turner a grand extended family, the more welcome after his father died in September 1829.

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

The Artist and his Admirers 1827

Watercolour and bodycolour on paper

support: 138 x 190 mm

Tate D22764

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.16

Joseph Mallord William Turner

The Artist and his Admirers 1827

Tate D22764

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Petworth: the White Library, looking down the Enfilade from the Alcove, 1827 1827

Watercolour, bodycolour and pen and ink on paper

support: 143 x 193 mm

Tate D22678

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.17

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Petworth: the White Library, looking down the Enfilade from the Alcove, 1827 1827

Tate D22678

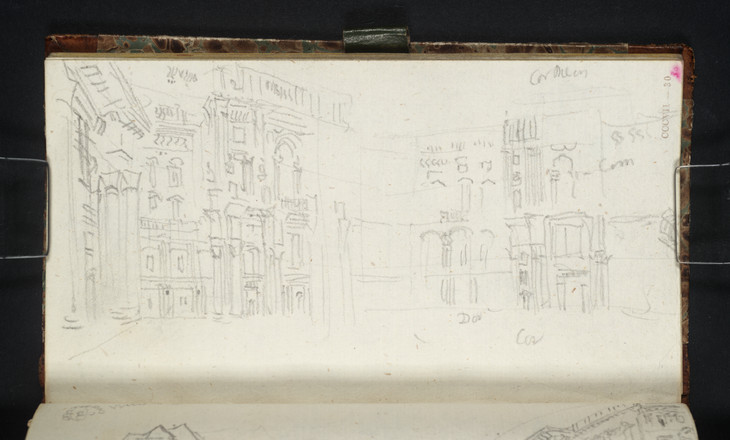

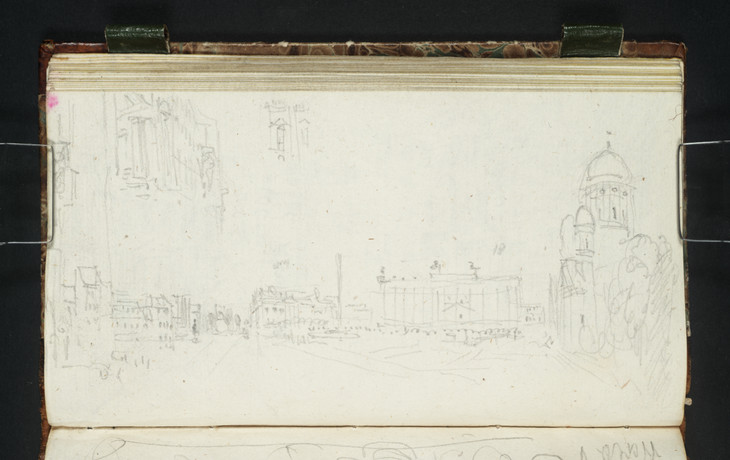

The loss was followed by that of Thomas Lawrence, West’s successor as President of the Royal Academy, in January 1830. Lawrence had judged Turner ‘indisputably the first landscape painter in Europe’7 and not long before the President’s death, in his first will made in 1829, Turner had endowed a chair and gold medal for landscape painting at the Academy. In Lawrence’s memory, Turner exhibited a watercolour of his funeral at St Paul’s Cathedral (Tate D25467). Later, in 1842, he commemorated, from imagination, the burial of Wilkie (to whom he had long been reconciled) at sea off Gibraltar (Tate N00528). By such gestures Turner assumed the mantle of a leader of his profession, acting on behalf of his colleagues. In 1832, he joined a committee to investigate the provision of space for the Academy alongside the National Gallery, and in 1836 proposed a farewell dinner in its old premises in Somerset House. One reason for extensive European tours in 1833 and 1835 may have been to investigate newly-built cultural institutions such as those designed by Karl Friedrich Schinkel in Berlin (figs.18 and 19).

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Berlin: The Internal Courtyard of the Schloss 1835

Graphite on paper

support: 162 x 89 mm

Tate D31078

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.18

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Berlin: The Internal Courtyard of the Schloss 1835

Tate D31078

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Berlin: View down Unter den Linden and across the Lustgarten to the Zeughaus, Lustgarten, Fountain, Museum and Domkirche, from the North-Eastern Corner of the Schloss (Detail of Schloss Façade in Sky) 1835

Graphite on paper

support: 162 x 89 mm

Tate D31079

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.19

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Berlin: View down Unter den Linden and across the Lustgarten to the Zeughaus, Lustgarten, Fountain, Museum and Domkirche, from the North-Eastern Corner of the Schloss (Detail of Schloss Façade in Sky) 1835

Tate D31079

William Parrott

Turner on Varnishing Day 1846

Oil on panel

4500 x 4370 mm

Museums Sheffield

Fig.20

William Parrott

Turner on Varnishing Day 1846

Museums Sheffield

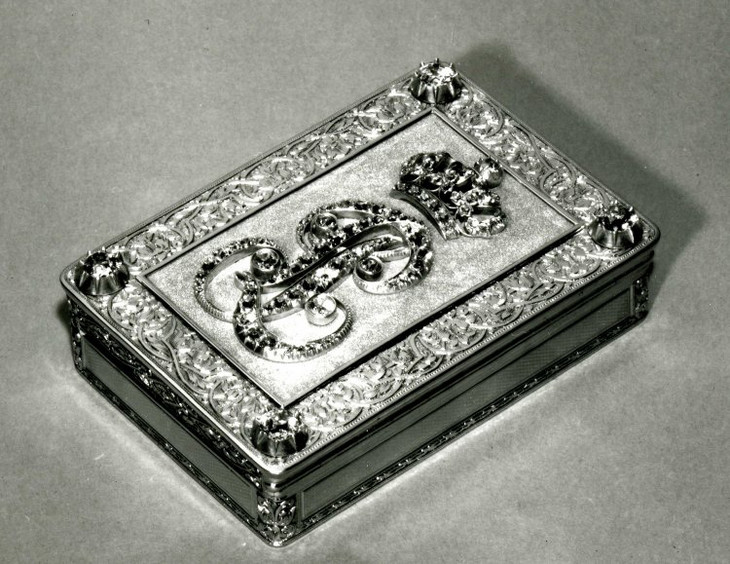

Turner could no more escape controversy in this later period than when he first came to prominence. In 1836 a virulent review in Blackwood’s Magazine by the Revd. John Eagles moved John Ruskin – then only seventeen – tospring to Turner’s defence. At first wary of his enthusiasm, Turner advised Ruskin not to publish it. Following correspondence, they met in 1840 at the house of Turner’s agent Thomas Griffith, and in 1843 Ruskin published the first volume of his book Modern Painters – placing Turner at their head. While critics accused Turner of extravagance and exaggeration, outdoing each other with comparisons of his pictures to lobster salad, soapsuds and whitewash, beetroot or mustard, Ruskin rooted his analysis (at least at first) in Turner’s truth to nature. He became the standard-bearer of a new generation of Turner admirers, now usually professional, middle class or newly rich, who embraced his work for its modernity. Their enthusiasm for watercolours as well as oils brought an upsurge of work in the medium in the last decade of Turner’s working life, increasingly directed towards independent subjects and watercolour ‘pictures’ rather than the demands of engravers and publishers. From 1842 Griffith was tasked to offer sample studies to clients, to attract commissions. Reflecting the cosmopolitan, European character of Turner’s mature art as well as its most advanced techniques, the subjects were mainly Swiss, arising from summer tours since 1841. Turner made his last visit to Switzerland in 1844. His health was failing and in 1845 he could only manage two short trips to France. On the second he dined with King Louis-Philippe, whom he had known when the future king was in exile at Twickenham, and who had since presented him with a gold snuff-box (fig.21). The previous autumn, he had watched the King arrive at Portsmouth for a state visit to Queen Victoria.

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

The Dogano, San Giorgio, Citella, from the Steps of the Europa exhibited 1842

Oil paint on canvas

support: 616 x 927 mm

Tate N00372

Presented by Robert Vernon 1847

Fig.22

Joseph Mallord William Turner

The Dogano, San Giorgio, Citella, from the Steps of the Europa exhibited 1842

Tate N00372

John Wykeham Archer

House of J.M.W.Turner, 6 Davis Place, Chelsea 1852

Watercolour with bodycolour over graphite on paper

375 x 273 mm

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.23

John Wykeham Archer

House of J.M.W.Turner, 6 Davis Place, Chelsea 1852

© The Trustees of the British Museum

47 Queen Anne Street West, photographed in the 1880s

Fig.24

47 Queen Anne Street West, photographed in the 1880s

George Jones

Turner's Body lying in State, 29 December 1851 1851

Oil on millboard

1400 x 2300 mm

Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Fig.25

George Jones

Turner's Body lying in State, 29 December 1851 1851

Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

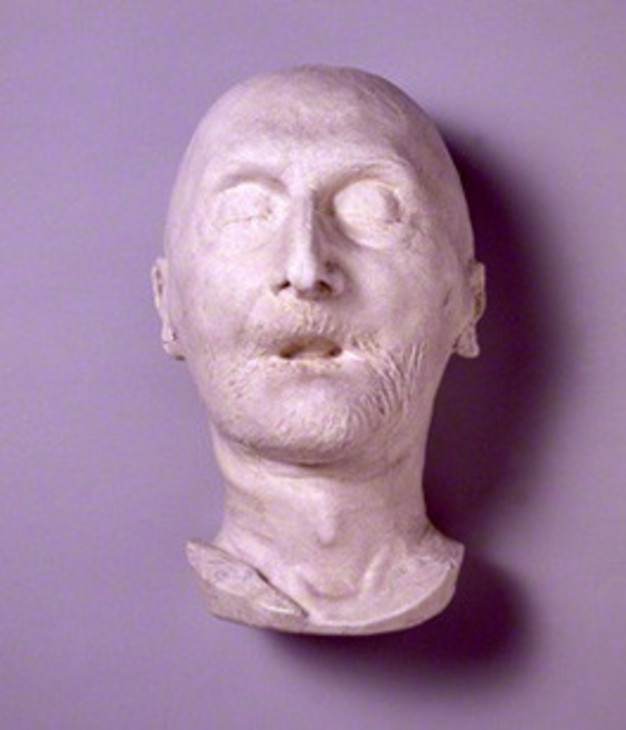

Plaster cast of death-mask of J.M.W. Turner 1851 Attributed to Thomas Woolner

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Fig.26

Plaster cast of death-mask of J.M.W. Turner 1851 Attributed to Thomas Woolner

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Turner quoted by Walter Thornbury, The Life and Correspondence of J.M.W. Turner R.A., revised edn, London 1897, p.27.

Kenneth Garlick and Angus Macintryre eds., The Diary of Joseph Farington [13 May 1803], vol.VI, p.2030.

Evelyn Newby, ‘Joseph Farington (1747–1821)’, in Evelyn Joll, Martin Butlin and Luke Herrmann eds., The Oxford Companion to J.M.W. Turner, Oxford 2001, p..102.

Beaumont, via Farington[5 June 1815], quoted by Martin Butlin and Evelyn Joll, The Paintings of J.M.W. Turner, revised ed., New Haven and London 1984, p.94.

Willard Bissell Pope ed., The Diary of Benjamin Robert Haydon [28 November 1815], Cambridge, Mass., 1960, vol.I, p.484.

Letter from Lawrence to Dawson Turner, 26 April 1809, quoted by W.T. Whitley, Art in England, 1800–1820, Cambridge 1928, vol.1, pp.150-1.

Bartlett quoted by A.J. Finberg, The Life of J.M.W. Turner, R.A., Second Edition, Revised, with a Supplement by Hilda F. Finberg, Oxford 1961, p.438.

How to cite

David Blayney Brown, ‘Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851’, artist biography, December 2012, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www