Turner Bequest XXXVII 1–128a

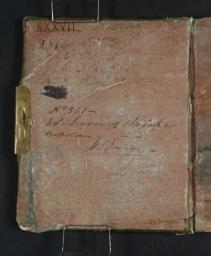

Sketchbook bound in boards covered in green vellum with one brass clasp

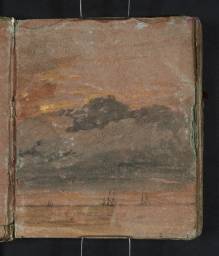

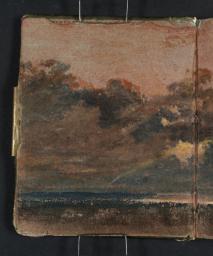

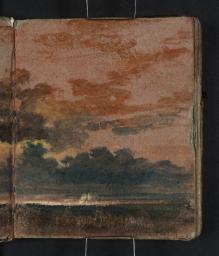

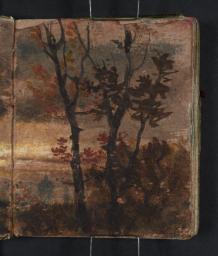

63 leaves and pastedowns of blue laid wrapping paper prepared with a red-brown wash; page size 113 x 93 mm

Maker unknown; watermark ‘6’ or ‘9’

Inscribed by Turner in ink ‘84 Studies for Pictures | [cop]ies of Wilson’ on a paper label on the front cover (D40762)

Numbered 361 as part of the Turner Schedule and endorsed by the Executors of the Turner Bequest inside front cover

63 leaves and pastedowns of blue laid wrapping paper prepared with a red-brown wash; page size 113 x 93 mm

Maker unknown; watermark ‘6’ or ‘9’

Inscribed by Turner in ink ‘84 Studies for Pictures | [cop]ies of Wilson’ on a paper label on the front cover (D40762)

Numbered 361 as part of the Turner Schedule and endorsed by the Executors of the Turner Bequest inside front cover

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Exhibition history

References

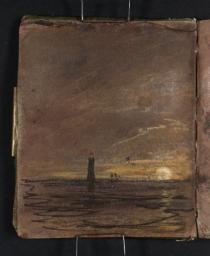

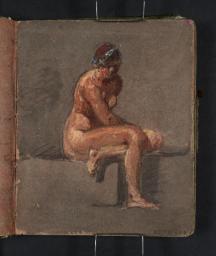

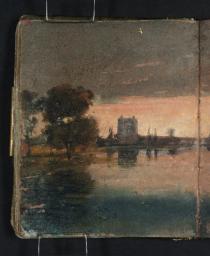

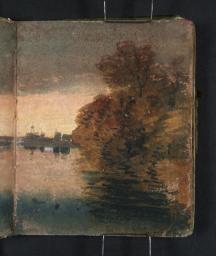

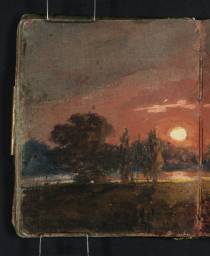

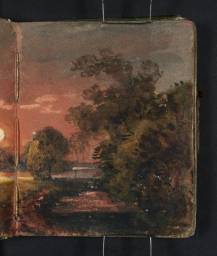

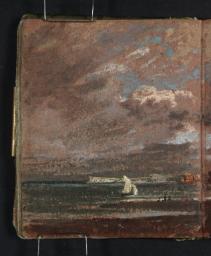

This is one of the most fascinating of Turner’s early sketchbooks, showing the twenty-one or twenty-two year-old artist exploring a wide range of visual experiences and developing his understanding of tonality under the stimulus of working for the first time at an ambitious level in oil.

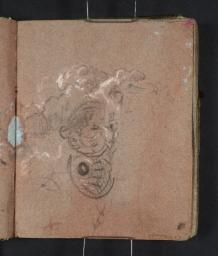

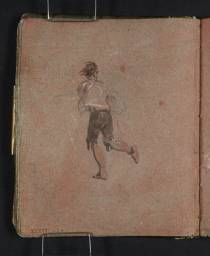

The reference in his label to the Welsh landscape painter Richard Wilson (?1713–1782) is accounted for by the presence in the book of a number of copies after Wilson’s pictures. Turner admired Wilson, and modelled his early painting style on his – though not, interestingly enough, in either the Moonlight, a Study at Millbank of 1797 (Tate N00459)1 or the Fishermen at Sea of 1796 (Tate T01585),2 where the influence is more probably that of Claude-Joseph Vernet (1714–1789), whose work is also apparently copied here on folios 51 verso–52 recto (D01221–D01222; Turner Bequest XXXVII 104–105). The more painterly technique of Wilson seems to have affected Turner’s use of his media in many of these studies: on a prepared reddish ground he works in chalks and gouache, neither of which he had much employed in his sketchbooks hitherto, and handles them with striking breadth and energy. The intense, vividly coloured drawings are often brought to a degree of finish that, despite their small size, gives them the presence of paintings. Even a slight study like the rapid sketch of a figure on the sea shore on folio 37 verso (D01193; Turner Bequest XXXVII 76) adumbrates important themes of Turner’s art, and indeed of Romantic painting generally. This book might most accurately be described as the first in a series that he was later to identify as containing ‘Studies for Pictures’; see the sketchbook of that name, in use around 1799–1802 (Tate; Turner Bequest LXIX).

Although it is difficult to identify many of the views recorded here, it seems clear that the book was used by Turner in places in and near London, including Westminster (folios 23 verso–24 recto; D01163–D01164 (Turner Bequest XXXVII 46–47), Blackheath and Lewisham (where he had pupils; see the ‘Copy-Drawings 1794–8’ section of the present catalogue, especially Tate D00868; Turner Bequest XXXII L), and in East Kent, around Margate; the drawing on folios 14 verso–15 recto (D01145–D01146; Turner Bequest XXXVII 28–29) appears to be a view of that town and on folio 56 verso (D01231; Turner Bequest XXXVII 114) there is an unmistakable view of Reculver, a few miles from Margate along the north Kent coast. Compare the drawing of Reculver in the Studies near Brighton book (Tate D00731; Turner Bequest XXX 2), a sketchbook with which this has much in common; see below. A particularly interesting group of drawings here is the series of church interiors, apparently made in and around London, and usually showing the churches in use during services. They are exceptionally rich in carefully observed detail both of people and of architecture, and in several the medium of gouache is exploited to obtain striking effects of chiaroscuro. It is noteworthy that Turner has seized on the fact that an oblique view of a medieval church, from, say, an aisle looking across the nave or into the chancel, yields dramatic contrasts of light and shade, with architectural spaces opening out of each other to construct intricate compositions in which his pictorial interests are brought to the fore.

It is hard to avoid the conclusion that the experiments in this book were closely connected to his work at this time on his first exhibited oil paintings. These were Fishermen at Sea, which appeared at the Academy’s summer exhibition in 1796, and the small Moonlight: a study at Millbank, shown the following year (both Tate; see above). Both asserted a virtuoso capacity to render effects of light at night; it is likely the more modest Millbank subject was actually painted first as a trial, but not exhibited until the larger and more ‘sensational’ Fishermen at Sea had had its due effect on the critics and public. Turner’s ambitions are manifest in this strategy, and they are reflected in every passionate page of the Wilson sketchbook. A further Academy exhibit is linked with the book, in the form of studies for figures on folios 7 verso, 8 verso and 9 recto (Tate D01131, D01133, D01134; Turner Bequest XXXVII 14, 16, 17) used in Fishermen coming ashore at Sun Set, previous to a Gale (the ‘Mildmay Seapiece’) of 1797, a canvas no longer traced, and known only through the plate of it included in the Liber Studiorum.3 This was evidently the ‘major’ oil painting of that season, the Millbank sent to the same exhibition being, as it was originally conceived, a modest experiment. A study of moonlight over the sea, perhaps connected with these ventures, is in the Studies near Brighton sketchbook (Tate D00828; Turner Bequest XXX 87).

A barely decipherable list of place-names inside the back cover (D01244; Turner Bequest XXXVII 127) of the present book indicates that Turner was using it when he planned his tour of the North of England in 1797 (see North of England sketchbook; Tate; Turner Bequest XXXIV), and indeed it seems that he actually took the book with him, although it was in all probability already almost full, and only one drawing testifies to its employment during that journey: the study of the Lilburn Tower of Dunstanburgh Castle on folios 46 verso–47 recto (D01211–D01212; Turner Bequest XXXVII 94–95). Although this is fairly generalised, it seems altogether too romantic an image to have been copied by Turner from another artist’s work, or from a print.

Technical notes

How to cite

Andrew Wilton, ‘Wilson Sketchbook 1796–7’, sketchbook, September 2012, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, November 2014, https://www