Walter Richard Sickert Claude Phillip Martin 1935

Walter Richard Sickert,

Claude Phillip Martin

1935

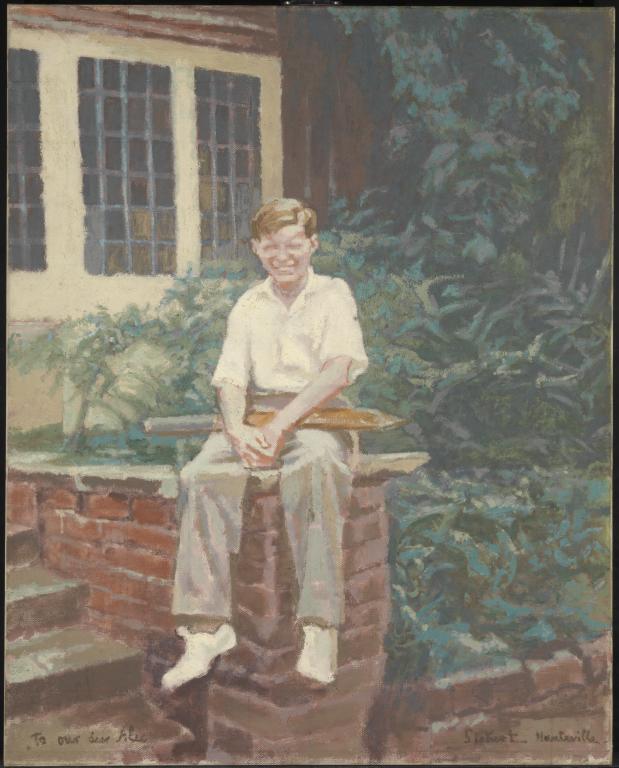

This portrait of the fourteen-year-old Claude Phillip Martin, Alec and Ada Martin’s youngest son, was taken both from life as well as photographs. The only one of the Martins’ six children to sit for Sickert, he is rendered on a smaller canvas and in a higher-key palette than the portraits of his parents (T00221 and T00222). Casually seated on a brick wall in the garden of the Martins’ house at Kingsgate, Claude Phillip rests a cricket bat across his lap, squinting calmly at the viewer through bright sunlight.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Claude Phillip Martin

1935

Oil paint on canvas

1270 x 1016 mm

Inscribed by the artist in brown paint ‘Sickert, Hauteville’ bottom right and ‘To our dear Alec’ bottom left

Presented by Sir Alec Martin, K.B.E., through the National Art Collections Fund 1958

T00223

1935

Oil paint on canvas

1270 x 1016 mm

Inscribed by the artist in brown paint ‘Sickert, Hauteville’ bottom right and ‘To our dear Alec’ bottom left

Presented by Sir Alec Martin, K.B.E., through the National Art Collections Fund 1958

T00223

Ownership history

Commissioned from the artist by Sir Alec Martin 1935, by whom presented through the National Art Collections Fund to Tate Gallery 1958.

Exhibition history

1981–2

Late Sickert: Paintings 1927 to 1942, (Arts Council tour), Hayward Gallery, London, November 1981–January 1982, Sainsbury Centre for the Visual Arts, University of East Anglia, Norwich, March–April 1982, Wolverhampton Art Gallery, April–May 1982 (25, reproduced).

1989–90

W.R. Sickert: Drawings and Paintings 1890–1942, Tate Gallery, Liverpool, March 1989–February 1990, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1990 (40, reproduced).

1990

From Beardsley to Beaverbrook: Portraits by Walter Richard Sickert, Victoria Art Gallery, Bath, May–June 1990 (48, reproduced on front cover).

1992–3

Sickert: Paintings, Royal Academy, London, November 1992–February 1993, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, February–May 1993 (121, reproduced).

1998

James McNeill Whistler, Walter Richard Sickert, Fundación ‘La Caixa’, Madrid, March–May 1998, Museo de Bellas Artes, Bilbao, May–July 1998 (91, reproduced).

References

1960

National Art Collections Fund Fifty-Sixth Annual Report 1959, London 1960, p.21.

1960

Lillian Browse, Sickert, London 1960, p.103.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, p.640.

1973

Wendy Baron, Sickert, London and New York 1973, pp.174, 383.

1975

Richard Morphet, ‘The Modernity of Late Sickert’, Studio International, vol.190, no.976, July–August 1975, p.35, reproduced p.37.

1988

Richard Shone, Sickert, Oxford 1988, reproduced pl.79.

2006

Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.721, pp.119, 538.

Technique and condition

Unlike the portraits of Sir Alec Martin (Tate T00221) and Lady Martin (Tate T00222), this work is painted on a plain-weave linen canvas bought from Winsor and Newton, which was sized and primed with a lean white primer that extends to the cut edges. The portrait is apparently taken both from life and from a photograph. Sickert initially drew directly onto the prepared canvas with a brush in black paint to outline his image working from life. He then appears to have begun painting, as he did the other two portraits, using two tones for each colour mixed with white on his palette; a development from his camaieu preparation but with the bright colours remaining visible as the final image.

When the first painting was dry the artist applied a black grid on top, probably in order to transfer the image from the photograph. The vertical and horizontal black painted lines form crosses and squares, which are partly covered by later campaigns but are also left deliberately visible in places. The use of a photographic image for each of the three portraits is visually integrated into the work, as discussed by the artist in a newspaper article in 1931:

The invention of the camera lucida and, later, the stabilisation of images on paper has been of infinite use to art. The sun has consented to stand still to provide us with documents. The artistic question has remained where it was. The relative interest of the documents collected as material for composition is the measure of the value of the artist.1

The paint is very lean oil applied by brush with little mixing and working on the canvas. Some of the initial black drawing lines are left visible and are used to emphasise the shadows, for example, the sitter’s left shoulder and arm, while others are reinstated or new ones added in the final stage to strengthen the image. Unlike Lady Martin (Tate T00222), the lights for each colour are not left as exposed white ground but are applied in white or near-white paint. It is likely that this work went through the same stages as the other portraits but was then worked on for longer, with a separate regime for the lights rather than a pre-planned third tone for each colour. Sickert may also have worked on areas other than the lights creating a more painterly image than the other portraits and leaving the work unvarnished.

Stephen Hackney

November 2005

Notes

How to cite

Stephen Hackney, 'Technique and Condition', November 2005, in Nicola Moorby, ‘Claude Phillip Martin 1935 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, January 2006, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Alec and Ada Martin had six children: three daughters, Mary, Nora (who died before her tenth birthday) and Joan, and three sons, Hugh Percy, William Alexander and Claude Phillip, the subject of Sickert’s 1935 portrait. Claude Phillip was born in 1921 and was named after his godfather, the art critic and keeper of the Wallace Collection, Sir Claude Phillips (1846–1924). In 1935 he was fourteen years old and a pupil at St Paul’s School, London.1 It is not known why Sickert painted only the Martins’ youngest son instead of the other children. The portrait forms the third of a trio with Sir Alec Martin (Tate T00221, fig.1) and Lady Martin (Tate T00222, fig.2), but is slightly smaller in size and uses a higher-keyed palette.

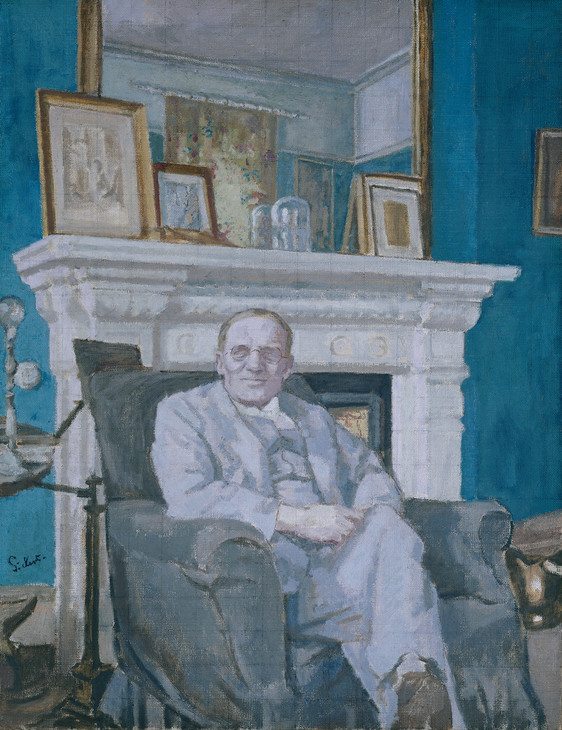

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Sir Alec Martin, KBE 1935

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1397 x 1079 mm

Tate T00221

Presented by Sir Alec Martin KBE through the Art Fund 1958

© Tate

Fig.1

Walter Richard Sickert

Sir Alec Martin, KBE 1935

Tate T00221

© Tate

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Lady Martin 1935

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1397 x 1079 mm

Tate T00222

Presented by Sir Alec Martin KBE through the Art Fund 1958

© Tate

Fig.2

Walter Richard Sickert

Lady Martin 1935

Tate T00222

© Tate

The portrait depicts the young boy dressed in a white open-necked, short-sleeved shirt, cream trousers and white plimsolls. He is sitting on a wall at the bottom of a flight of steps leading from the house in the background to the garden. Sir Alec Martin recalled that, unlike the portraits of himself and his wife, the portrait of his son was started in the garden of the Martins’ house, Marandellas, at Kingsgate.2 Most of the painting, however, was completed in Sickert’s studio, and the work is inscribed with the name of Sickert’s house in St Peter’s-in-Thanet, Hauteville. Lady Martin recalled that photographs were taken of her son for use in undertaking the commission and, indeed, the portrait has the feel of an informal snapshot.3 Richard Morphet has described Claude Phillip Martin as ‘at once banal and archetypal, lifelike and abstract, particular and almost banner-like, casual and timeless’ and has compared Sickert’s use of photographic material with Andy Warhol’s practice of selecting and enhancing photo-based images in his work.4 The sitter is holding a cricket bat across his lap as though he has just been called away from playing in the garden. His gaze is open and relaxed and he grins directly at the viewer, squinting slightly as though looking into the sun. Sickert’s treatment of the figure makes a feature of the harsh shadows in the creases of Claude Phillip’s trousers and the lack of detail in his face as though aestheticising and replicating the effect of halation, the blurring of an object in the glare of bright daylight.

The calm banality portrayed by the portrait is sadly at odds with the sitter’s subsequent life, sketched out in a letter to the Tate Gallery by his father.5 Claude Phillip’s final year at school coincided with the outbreak of the Second World War and on leaving education he joined up and fought with the British army in Austria. He returned from the conflict physically uninjured but his experiences as a soldier caused him to have a breakdown soon after his return and he tragically never fully recovered his health. He died in December 1979, aged fifty-eight.

Nicola Moorby

January 2006

Notes

Related biographies

Related essays

- After Camden Town: Sickert’s Legacy since 1930 Martin Hammer

Related catalogue entries

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Claude Phillip Martin 1935 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, January 2006, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www