Walter Richard Sickert Study for 'Ennui' 1913-14

Walter Richard Sickert,

Study for 'Ennui'

1913-14

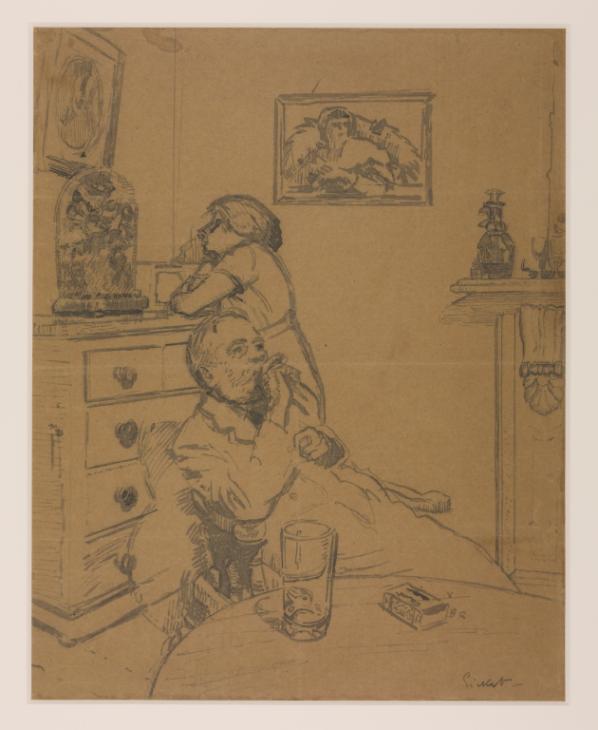

This pen and ink drawing on fawn-coloured paper is one of approximately fourteen preparatory studies Sickert completed for the finished oil painting Ennui (Tate N03846). A full compositional sketch situating Marie and Hubby in relation to the room’s inanimate objects, it contains all the elements that appear in the final painting and presents a slightly wider view, to both left and right, of the narrow interior. Sickert later made small adjustments, most notably to the posture of each figure, in order to maximise the feeling of languor.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Study for ‘Ennui’

1913–14

Ink on paper

422 x 340 mm

Inscribed by the artist in ink ‘Sickert -’ bottom right and colour note ‘Y | B R’ next to matchbox

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1960

T00350

1913–14

Ink on paper

422 x 340 mm

Inscribed by the artist in ink ‘Sickert -’ bottom right and colour note ‘Y | B R’ next to matchbox

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1960

T00350

Ownership history

... ; Alfred Jowett, sold Christie’s, London, 17 July 1959 (119), bought Agnew’s, London, from whom acquired by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1960.

Exhibition history

1941

Sickert, National Gallery, London, August–December 1941 (106).

1953

An Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings by Walter Sickert, Arts Council, Diploma Galleries, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, January 1953 (84, as ‘Ennui’).

1959

Agnew’s, London, March–April 1959 (235).

1965

Decade 1910–20, (Arts Council tour), Leeds City Art Gallery, May 1965, Reading Art Gallery, May–June 1965, Manchester City Art Gallery, July 1965, Glasgow Art Gallery and Museum, July–August 1965, Leicester Museum and Art Gallery, September 1965 (36).

2004–5

Walter Sickert: ‘drawing is the thing’, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, October–December 2004, Southampton City Art Gallery, January–March 2005, Ulster Museum, Belfast, April–June 2005 (5.11, reproduced).

References

1960

Lillian Browse, Sickert, London 1960, p.78.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, p.641.

1989

W.R. Sickert: Drawings and Paintings 1890–1942, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, Liverpool 1989, reproduced p.24.

1996

Anna Gruetzner Robins, Walter Sickert: Drawings, Aldershot and Vermont 1996, pp.16, 35, reproduced pl.50.

2000

Susan Sidlauskas, Body, Place, and Self in Nineteenth-Century Painting, Cambridge and New York 2000, p.137, reproduced fig.52.

2004

Nicola Moorby, ‘“A long chapter in the ugly tale of commonplace living”: The Evolution of Sickert’s “Ennui”’, in Walter Sickert: ‘drawing is the thing’, exhibition catalogue, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester 2004, no.5.11, pp.14, 112, reproduced p.118.

2006

Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.418.6, p.408.

Technique and condition

This is a preparatory study for the painting Ennui (Tate N03846). The drawing is executed in pen and ink on a fawn-coloured, machine-made wove paper. The top edge of the sheet is unevenly cut and the remainder are cut straight, and there are fold marks running vertically down the centre and horizontally across the sheet, suggesting that it was a loose leaf that has been transported. Pinholes in the top corners indicate that the paper was either pinned to a board or had another drawing pinned onto it to transfer the image. The drawing is executed directly onto the paper in black ink with no evidence of any initial sketching in dry graphic media, the design having been resolved in other preparatory studies for the painting. It appears that the artist diluted the black ink to get two variations (black and greyish) in tone. The greyish ink looks like watercolour where it is applied with bold nib and there is some additional application of the darker ink to reinforce points in the composition.

Tomoko Kawamura

November 2005

How to cite

Tomoko Kawamura, 'Technique and Condition', November 2005, in Nicola Moorby, ‘Study for ‘Ennui’ 1913–14 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, May 2004, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Ennui c.1914

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1524 x 1124 mm; frame: 1741 x 1340 x 110 mm

Tate N03846

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1924

© Tate

Fig.1

Walter Richard Sickert

Ennui c.1914

Tate N03846

© Tate

The first group focuses on the corporeal arrangement of the male and female figures so crucial to the expression of the painting’s theme of alienation and degeneration. The pose of the models is the same in each drawing. The man, Hubby, is seated and smoking a cigar with the woman, Marie, standing behind him leaning on her arms slumped against the chest of drawers. However, close analysis of the separate images reveals a progressive fine tuning of the poses through subtle alterations in the positioning of the figures. For example, in Study for ‘Ennui’ (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford),3 a pen and ink drawing over black chalk, Hubby’s position, revealed through his head and shoulders, is upright and his right hand obscures much of the lower part of his face. Behind him, Marie stands as a separate entity with her left arm well clear from the top of his head. Her face is seen in profile with her mouth partially open. This pose is repeated in the early oil sketch, Ennui c.1913 (Rockingham Castle, formerly Cobbledick and Culme Seymour).4 Over the course of several drawings Sickert gradually modified the motif to create a more expressive relationship. In Study for ‘Ennui’ (Leeds City Art Gallery),5 Hubby and Marie seem to have sunk into their poses so they appear more weighed down by lassitude. Hubby has been tilted fractionally back while Marie leans further in towards him and her arm now occupies the same pictorial space as the top of his head. This pose is closer to that represented in the second oil sketch, Ennui c.1913 (The Royal Collection).6

The second group of associated drawings are of details, providing closely observed depictions of the individual components of the design. Sickert made four detailed studies recording the appearance of the oval painting and the glass bell jar (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford);7 the decanter and wine glass on the mantelpiece and the light falling on the edge of the gilt picture frame (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford);8 the glass jar next to the cigar box with the head and arms of Marie and Hubby, and the corner of the picture frame again (Leeds City Art Gallery);9 and, finally, a single sheet containing studies of the decanter and wine glass, the pint glass and the horizontal painting of the woman with bare shoulders (Leeds City Art Gallery).10 These drawings delineate in fine detail the individual appearance of the items and their relationship to each other, for example the way the frame of the picture is visible through the top of the glass dome and the play of light on the cut surfaces of the decanter. The sheet of drawings in the collection of Leeds City Art Gallery showing the glass jar of stuffed birds has a diagram of shapes in the right-hand corner with colour notes. The shapes relate to the individual birds in the bell jar, and show how important drawn studies were to Sickert’s painting process.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Study for ‘Ennui’: Hubby and Marie c.1913

Pen and brown ink over black chalk, with red ink, on pale brown paper

380 x 280 mm

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Fig.2

Walter Richard Sickert

Study for ‘Ennui’: Hubby and Marie c.1913

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Tate’s drawing is a full compositional pen and ink sketch showing all the pictorial elements of the design. The details closely resemble Tate’s painting except that the drawing reveals slightly more of the right and left side of the room while showing less of the table top in the foreground. This means that in the drawing the whole of the vertical painting on the wall is visible instead of just a partial view, and there are two wine glasses sitting on the mantelpiece instead of one. The matchbox on the table in the foreground faces the opposite direction to its final position in the painting and Sickert has inscribed the letters ‘Y’, ‘B’ and ‘R’ beside it, indicating colour notes ‘yellow’, ‘blue’ and ‘red’. The alignment of the figures is marginally different from their position in the painting and is closer to the preliminary oil painting Ennui c.1913 (Rockingham Castle, formerly in the collection of Cobbledick and Culme Seymour). The position of Hubby is almost identical in the oil study whereas in Tate’s painting he is turned slightly more towards his left and leaning further back in the chair. Similarly, the line of Marie’s back is more upright in the drawing and the early oil sketch. In Tate’s painting she is slumped further forward and the line of her skirt extends past Hubby’s left hand to the arm of the chair. It is therefore likely that Sickert completed Tate’s drawing at an early stage of the evolutionary process and it was one of the first times he mapped out the entire composition with all the components that appear in the final painting.

Gabriel White has made the connection between Sickert’s preference for drawing with pen and ink and his interest in etching and his early training under Whistler.14 As a painter, Sickert’s technique was based upon building up thin layers of colour applied in broken patches which usually had the effect of blurring form and destabilising contour. Conversely, as a draughtsman, Sickert conceived the image in terms of outline. Some of the marks made in Tate’s drawing predict the treatment of the subject as an etching, for example the repeated horizontal parallel lines depicting the side of the chest of drawers and the definition of the volume of the glass decanter with thin strokes and cross hatching.

Nicola Moorby

May 2004

Notes

See Nicola Moorby, ‘“A long chapter in the ugly tale of commonplace living”: The Evolution of Sickert’s Ennui’, in Walter Sickert: ‘drawing is the thing’, exhibition catalogue, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester 2004, pp.11–14; Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, nos.418.5–18.

Ruth Bromberg, Walter Sickert Prints: A Catalogue Raisonné, New Haven and London 2000, pp.183–4; Baron 2006, no.418.7.

Ashmolean Museum, WA 1949.219. Reproduced in Whitworth Art Gallery 2004, (5.03, p.115); Baron 2006, no.418.17.

Leeds City Art Gallery, 2.4/47. Baron 2006, no.418.9; reproduced in Whitworth Art Gallery 2004 (5.15, p.110).

Baron 2006, no.418.2; reproduced in Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992 (80).

Ashmolean Museum, WA 1949.220. Baron 2006, no.418.18; reproduced in Whitworth Art Gallery 2004 (5.07).

Ashmolean Museum, WA 1949.221. Baron 2006, no.418.16; reproduced in Whitworth Art Gallery 2004 (5.08).

Leeds City Art Gallery, 23.1/51 (iv). Baron 2006, no.418.14; reproduced in Whitworth Art Gallery 2004 (5.09).

Leeds City Art Gallery, 23.1/51 (v). Baron 2006, no.418.15; reproduced in Whitworth Art Gallery 2004 (5.10, p.117).

Related biographies

Related essays

- After Camden Town: Sickert’s Legacy since 1930 Martin Hammer

- Questions of Artistic Identity, Self-Fashioning and Social Referencing in the Work of the Camden Town Group Andrew Stephenson

- Walter Sickert and Contemporary Drama William Rough

- From Drawing Room to Scullery: Reading the Domestic Interior in the Paintings of Walter Sickert and the Camden Town Group Juliet Kinchin

- The Evolution of Painting Technique among Camden Town Group Artists Stephen Hackney

- The Camden Town Group: Then and Now Ysanne Holt

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Study for ‘Ennui’ 1913–14 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, May 2004, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www