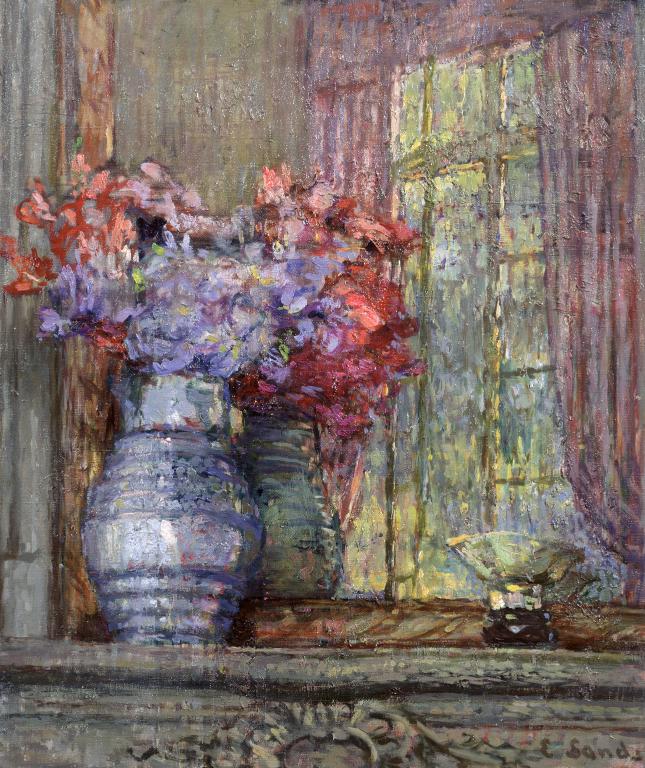

Ethel Sands Flowers in a Jug ?1920s

© The estate of Ethel Sands

Ethel Sands,

Flowers in a Jug

?1920s

© The estate of Ethel Sands

Flowers, still lifes and domestic interiors are the primary subjects of Ethel Sands’s painting; they are here combined in a depiction of an ornate mantelpiece at the Château d’Auppegard, near Dieppe. Blue, purple and red flowers stand in a blue jug near a small bowl, all reflected in a mirror that leans against the wall. A window draped in rose-coloured curtains is visible in the reflection, giving spatial depth to the tight composition.

Ethel Sands 1873–1962

Flowers in a Jug

?1920s

Oil paint on canvas

560 x 457 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘E. Sands’ in black paint bottom right

Bequeathed by Colonel Christopher Sands 2000, accessioned 2001

T07809

?1920s

Oil paint on canvas

560 x 457 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘E. Sands’ in black paint bottom right

Bequeathed by Colonel Christopher Sands 2000, accessioned 2001

T07809

Ownership history

By descent from the artist to her nephew Christopher Sands 1962, by whom bequeathed to Tate 2000.

Technique and condition

Ethel Sands chose a fine plain-weave linen canvas for this painting that appears to have been supplied by a French artists’ colourmen, part of a stamp bearing the inscription ‘toiles et couleurs’ marking the back of the canvas. The canvas appears to have been re-stretched at some point but it is not known when or why. The canvas has probably been sized and had been primed with an off-white primer, which extends to the cut edges of the canvas and is applied in a fine even layer, allowing the texture of the canvas to show through.

It is difficult to discern any initial drawing beneath subsequent layers of paint and there is no evidence of any initial drawing in graphic media. Sands appears to have marked out the outline of the composition directly onto the primed canvas in a diluted brown-coloured oil paint. She blocked in thin, lean areas of colour within these lines, later adding detail and shape with thicker oil paint and square-tipped brushes laid on in vertical, horizontal and diagonal lines to define the shape of the architectural features and curved strokes to form the shape of the vase and its reflection. The painting of the vase is lively with thick impasto, whereas its reflection is flatter, receding slightly. The paint is laid on wet-in-wet, in single touches of bright colour, lying adjacent to one another over a more muted background. In ultraviolet light the bright pink pigment in the flowers fluoresces bright orange suggesting a significant content of madder pigment. The ground is more or less completely covered by subsequent layers and the painting is highly worked and finished. The paint appears so glossy in areas that it might seem to be varnished but it appears that the paint is simply more medium-rich in these areas.

Annette King

November 2004

How to cite

Annette King, 'Technique and Condition', November 2004, in Nicola Moorby, ‘Flowers in a Jug ?1920s by Ethel Sands’, catalogue entry, July 2003, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Ethel Sands specialised in painting domestic interiors, still lifes and flower subjects, all of which are combined in her painting Flowers in a Jug. The work shows a large blue jug containing blue, purple and red flowers standing on a mantelpiece beside a small shallow bowl. Behind the ornaments is a large mirror with a gilt frame in which is reflected a view of an open window surrounded by a lilac pelmet and curtains, creating an illusion of space and depth. The location of the picture is not recorded but the appearance of the interior indicates that it was probably painted at the Château d’Auppegard, Nan Hudson’s seventeenth-century country house near Dieppe, which she had purchased in 1920 (see Tate T07810). Sands joined her friend at Auppegard every summer and together they carefully refurbished and decorated the entire house. The writer Virginia Woolf, visiting in 1927, described it as ‘a very narrow house, all window, laid with pale bright Samarcand rugs, & painted greens and blues, with lovely “pieces”, & great pots of carefully designed flowers arranged by Loomas [the butler]’.1

In an article in Vogue in 1923, Allan Walton wrote that the hall and the drawing room of Auppegard were panelled with ‘old, painted woodwork of pale, warm grey’,2 part of which seems to be visible to the left of the mirror frame in Sands’s painting. The ornate marble mantelpiece is in keeping with a period building on the scale of the château and the partially open, large window festooned with lilac curtains is also suggestive of the carefully chosen fabrics installed by the two women at Auppegard. The house had an unusually large number of windows on both the ground and first floor, making the building extremely light inside. The style of the windows, which were ‘glazed with old Dutch glass of greenish colour’,3 matches the appearance of the window in the painting, with multiple square panes within a wooden framework opening in the middle.4 Sands produced a number of paintings of both the exterior and interior of Auppegard, for example A Spare Room, Château d’Auppegard c.1925 (Government Art Collection),5 Girl Sewing, Auppegard c.1920–5 (private collection),6 and a view of the drawing room entitled The White Clock c.1930 (private collection).7 She also painted a portrait of Hudson at the house during the 1930s (private collection).8 Flowers in a Jug is probably a view of one of the ground-floor rooms, painted during the 1920s.

Described by the essayist and critic Logan Pearsall Smith (1865–1946) as ‘a piece of perfection, a bit of Paradise from the age of Gold’,9 the Château d’Auppegard was a far cry from the dingy backstreets and seedy interiors of Fitzroy Street and Camden Town. Not only did Sands and Hudson work extremely hard on its renovation and decoration, but their very daily existence was something of a work of art in itself. Both ladies were fastidious by nature and maintained the highest standards of tidiness and beauty in their home at all times. The Bloomsbury painter Vanessa Bell stayed at Auppegard during 1927, when she and Duncan Grant painted some murals on the walls of the château’s loggia. She wrote to Roger Fry:

Please send us a glimpse of ordinary rough and tumble, dirty every-day existence. I am beginning to be in danger of collapse from rarefaction here. The strain to keep clean is beginning to tell. Duncan shaves daily – I wash my hands at least five times a day – but in spite of all, I know I’m not up to the mark. The extraordinary thing is that it’s not only the house but also the garden that’s in such spotless order. It’s almost impossible to find a place into which one can throw a cigarette end without its becoming a glaring eyesore.10

Bell did not think a great deal of Sands’s painting, regarding it as an inevitable product of the older woman’s lifestyle. Sands did paint interiors that reflected her environment and surroundings but her paintings should be seen in the context of a number of works that take as their theme private space and everyday environment, particularly those which use the recurring motif of a still life on a mantelpiece.

Despite the wide variety of styles and artistic beliefs encompassed by the term ‘Camden Town’, many of the artists of this circle shared a concern with conveying through their art the experience of ordinary, everyday life. Subjects derived from the domestic arena were therefore popular since they reflected the true nature of real existence, and the casual and lowly nature of everyday items was invested with meaning through their description in modernist terms. Friend and patron Louis Fergusson, for example, talked about Gilman’s love of painting the material objects of day-to-day life that through his art took on the significance of ‘household gods’.11 Images such as the bureau stacked with tea cups and plates in Gilman’s Shopping List 1912 (British Council),12 or the jumble of furniture and ornaments in the middle-class room of Interior c.1914–15 (private collection),13 claim the commonplace as worthy of serious artistic contemplation, almost as though these paintings were a kind of religious icon through which the viewer could access the fundamental essence of modern life.

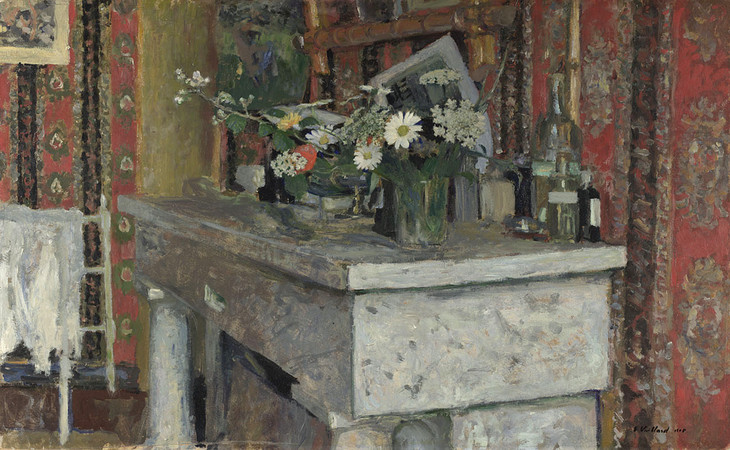

Edouard Vuillard 1868–1940

The Mantelpiece (La Cheminée) 1905

Oil paint on canvas

514 x 775 mm

National Gallery, London

Photo © National Gallery, London

Fig.1

Edouard Vuillard

The Mantelpiece (La Cheminée) 1905

National Gallery, London

Photo © National Gallery, London

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Mantelpiece c.1906–7

Oil paint on canvas

762 x 508 mm

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.2

Walter Richard Sickert

The Mantelpiece c.1906–7

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

The art historian Wendy Baron has identified the theme of the mantelpiece still life as an offshoot of Walter Sickert’s paintings of interiors with figures,14 although Sands may also have been aware of Edouard Vuillard’s painting, The Mantelpiece (La Cheminée) 1905 (fig.1). Large decorative fire surrounds in marble or wood became fashionable during the Victorian period, emphasising the open fire as the focus of a room with its symbolic notions of the domestic hearth and home.15 By the early twentieth century these mantelpieces, usually surmounted by a large overmantel mirror and a shelf broad enough to accommodate an array of ornaments, were a standard feature in most homes,16 as can be seen in the dingy and claustrophobic interior of Sickert’s famous painting, Ennui c.1914 (Tate N03846). They were a feature instantly recognisable as characteristic of their time and appear in a number of paintings of Camden Town interiors by Sickert and his circle such as The Mantelpiece c.1906–7 (fig.2) by Sickert, and Spencer Gore’s Conversation Piece and Self-Portrait c.1910 (private collection).17 Artists developing a more self-consciously abstract style used the mantelpiece and the inevitable shelf of clutter as a subject, even in Duncan Grant’s and Vanessa Bell’s paintings of the same mantelpiece in Bell’s house at 46 Gordon Square, The Mantelpiece 1914 (Tate T01328, fig.3) and Still Life on Corner of a Mantelpiece 1914 (Tate T01133, fig.4), where, however, it holds a piece of hand-made Bloomsbury decoration.

Duncan Grant 1885–1978

The Mantelpiece 1914

Oil and collage of paper laid on board

support: 457 x 394 mm

Tate T01328

Purchased 1971

© The estate of Duncan Grant

Fig.3

Duncan Grant

The Mantelpiece 1914

Tate T01328

© The estate of Duncan Grant

Vanessa Bell 1879–1961

Still Life on Corner of a Mantelpiece 1914

Oil on canvas

support: 559 x 457 mm; frame: 614 x 512 x 49 mm

Tate T01133

Purchased 1969

© The estate of Vanessa Bell

Fig.4

Vanessa Bell

Still Life on Corner of a Mantelpiece 1914

Tate T01133

© The estate of Vanessa Bell

Sickert believed that serious art should ‘avoid the drawing-room and stick to the kitchen’,18 and much Camden Town painting follows this principle, eschewing upper-class refinement in favour of lower-class domesticity. Sands, however, whose own life was lived very much more in the drawing room than the kitchen, reflected her everyday environment within her paintings. Flowers in a Jug, and another Auppegard painting, The Mantelpiece, also known as The White Clock c.1930 (private collection),19 combine Sickert’s motif of the mantelpiece with Sands’s own appreciation and experience of elegant living and beautiful interiors. This was recognised by critics reviewing her solo exhibition at the Goupil Gallery in 1922. The Westminster Gazette described her work as revealing a ‘courage, rare nowadays, in confessing her liking for pretty things’ and talked about ‘the application of Sickert virtues to pleasant subjects’.20

Flowers in a Jug demonstrates an impressionist-like handling of paint and interest in colour. The immediacy and looseness of the brushstrokes and the vibrancy of the colours suggests that Sands probably painted the picture directly in front of the subject. Even Sickert, who was always trying to persuade her to follow his example and paint from canvases squared up from preparatory drawings, conceded that working from nature was effective in the case of flower painting. He bombarded Sands with advice on her artistic development, but wrote to her, ‘There is a great beauty of prima painting. For flowers sketches &c. Don’t drop that.’ 21

Nicola Moorby

July 2003

Notes

Allan Walton, ‘The Château d’Auppegard, a Louis Quatorze Country House’, Vogue, November 1923, p.50.

Reproduced at Government Art Collection, http://www.gac.culture.gov.uk/work.aspx?obj=14788 , accessed July 2003.

Reproduced in The Painters of Camden Town 1905–1920, exhibition catalogue, Christie’s, London 1988 (114).

Reproduced in Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2008 (47).

Reproduced in Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, no.61.

Helen C. Long, The Edwardian House: The Middle Class House in Britain 1880–1914, Manchester and New York 1993, p.102.

Reproduced in From Sickert to Gertler: Modern British Art from Boxted House, exhibition catalogue, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh 2008 (25).

Related biographies

Related essays

Related catalogue entries

Related reviews and articles

- Walter Richard Sickert, ‘Idealism’ The Art News, 12 May 1910, p217..

- Louis F. Fergusson, ‘Harold Gilman’ in Wyndham Lewis and Louis F. Fergusson, Harold Gilman: An Appreciation, London: Chatto & Windus 1919, pp.19–32.

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Flowers in a Jug ?1920s by Ethel Sands’, catalogue entry, July 2003, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www