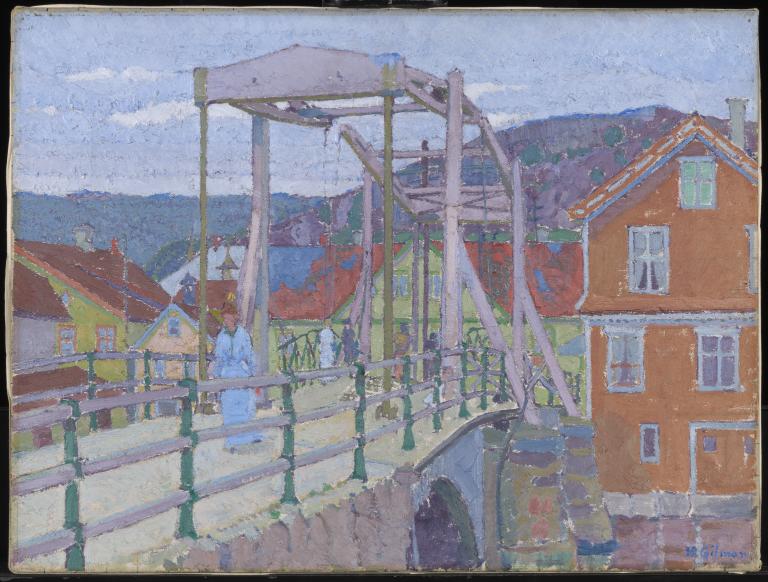

Harold Gilman Canal Bridge, Flekkefjord c.1913

Harold Gilman,

Canal Bridge, Flekkefjord

c.1913

Harold Gilman began this work while travelling in Norway, after recording the bridge in detailed pen drawings. Figures moving across the bridge give a sense of the architectural scale. The pervasive blues of the sky and surrounding landscape are tempered by the red rooftops and the muted tangerine of the house on the right-hand side.

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Canal Bridge, Flekkefjord

c.1913

Oil paint on canvas

464 x 615 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘H. Gilman’ bottom right, numbered along each edge and squared for transfer

Purchased (Grant-in-Aid) 1922

N03684

c.1913

Oil paint on canvas

464 x 615 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘H. Gilman’ bottom right, numbered along each edge and squared for transfer

Purchased (Grant-in-Aid) 1922

N03684

Ownership history

Purchased in 1915 at the London Group exhibition by Walter Taylor (1860–1943), from whom bought by Tate Gallery 1922.

Exhibition history

1913

Post-Impressionist and Futurist Exhibition, Doré Galleries, London, October 1913 (52, as ‘A Bridge in Norway’).

1915

The Second Exhibition of Works by Members of the London Group, Goupil Gallery, London, March 1915 (26, as ‘Flekkefjord’).

1915

Exhibition of Works by Members of the Cumberland Market Group, Goupil Gallery, London, April–May 1915 (6, as ‘A Bridge, Norway’).

1936–7

Empire Exhibition, Johannesburg Art Gallery, September 1936–January 1937 (426, as ‘Canal Bridge’).

1939

An Exhibition of Contemporary British Art, (British Council tour), Instytut Propogandy Sztuki, Warsaw, January–February 1939, Taidehalli-Konsthallen, Helsingfors, March 1939, Liljevalchs Konsthall, Stockholm, April–May 1939 (25, as ‘The Canal Bridge’).

1944–5

The Camden Town Group, (Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts tour), Wakefield Museum and Art Gallery, July 1944, Jordans School, Chalfont St Giles, August 1944, Ferens Art Gallery, Hull, August–September 1944, Shipley Art Gallery, Gateshead, September–October 1944, Atkinson Art Gallery, Southport, October–November 1944, Reading Museum and Art Gallery, December 1944, Hanley Public Museum and Art Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent, January–February 1945 (17, as ‘The Canal Bridge, Norway’).

1946–7

Modern British Pictures from the Tate Gallery, (British Council tour), Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, January–February 1946, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, March 1946, Raadhushallen, Copenhagen, April–May 1946, Musée du Jeu de Paume, Paris, June–July 1946, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Berne, August 1946, Akademie der Bildenden Künste, Vienna, September 1946, Narodni Galerie, Prague, October–November 1946, Muzeum Narodowe, Warsaw, November–December 1946, Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Rome, January–February 1947 (13, but 14 in Paris).

1947

Tate Gallery 1897–1947: Pictures from the Tate Gallery Foundation and Exhibition of Subsequent British Painting, Tate Gallery, London, May–September 1947 (3684, as ‘The Canal Bridge’).

1954–5

Harold Gilman 1876–1919, (Arts Council tour), Arts Council, London, January–December 1954, Manchester Art Gallery, November–December 1954, Tate Gallery, London, May–June 1955 (20a, not listed in catalogue).

1969

Harold Gilman 1876–1919: An English Post-Impressionist, The Minories, Colchester, March 1969, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, April–May 1969, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, May–June 1969 (20, as ‘The Bridge, Flekkefjord’, reproduced).

1981–2

Harold Gilman 1876–1919, (Arts Council tour), City Museum and Art Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent, October–November 1981, York City Art Gallery, November 1981–January 1982, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, January–February 1982, Royal Academy of Arts, London, February–April 1982 (41).

1982

Paint & Painting: An Exhibition and Working Studio Sponsored by Winsor & Newton to Celebrate Their 150th Anniversary, Tate Gallery, London, June–July 1982 (no number, reproduced p.89).

1998–9

Lucien Pissarro et le post-impressionisme anglais, Musée de Pontoise, November 1998–March 1999, Chateau-Musée, Dieppe, March–June 1999 (65, reproduced).

2002

Harold Gilman and William Ratcliffe, Southampton City Art Gallery, April–July 2002 (no number, reproduced).

2008

Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, Tate Britain, London, February–May 2008 (4, reproduced).

2008–9

A Countryman in Town: Robert Bevan and the Cumberland Market Group, Southampton City Art Gallery, September–December 2008, Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, January–March 2009 (no number).

References

1915

Frank Rutter, Sunday Times, 21 March 1915.

1938

Tate Gallery Illustrations, British School, London 1938, reproduced p.102.

1955

Dennis Farr, ‘Harold Gilman 1876–1919’, Burlington Magazine, vol.97, June 1955, p.184.

1962

John Rothenstein, The Tate Gallery, London 1962, reproduced p.253.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.1, London 1964, pp.234–5, reproduced pl.iv.

1979

Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, London 1979, pp.288, 332, 368.

1979

The Tate Gallery: An Illustrated Companion, London 1979, reproduced p.80.

1980

Simon Watney, English Post-Impressionism, London 1980, p.66, reproduced fig.39.

1982

Roy A. Perry, ‘Harold Gilman: Canal Bridge, Flekkefjord’, in Stephen Hackney (ed.), Completing the Picture: The Materials and Techniques of Twenty-Six Paintings in the Tate Gallery, London 1982, pp.77–81, reproduced p.79.

1988

Laura Wortely, British Impressionism: A Garden of Bright Images, London 1988, reproduced p.251.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.169.

Technique and condition

Canal Bridge, Flekkefjord is painted in artists’ oil paints on stretched primed canvas. The cloth is plain close-weave linen, and an illegible stamp on the back enclosing the handwritten digits ‘12741’ is probably a canvas batch number. The canvas is probably sized but no distinct layer is detectable. The priming extends to the tacking edges, retaining the weave texture, and is composed of a single layer of lead white with a trace of kaolin. This type of canvas and the basic preparation is consistent with that found on all of Gilman’s paintings in Tate’s collection (see also Tate T00096).

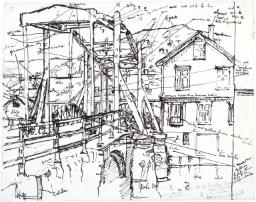

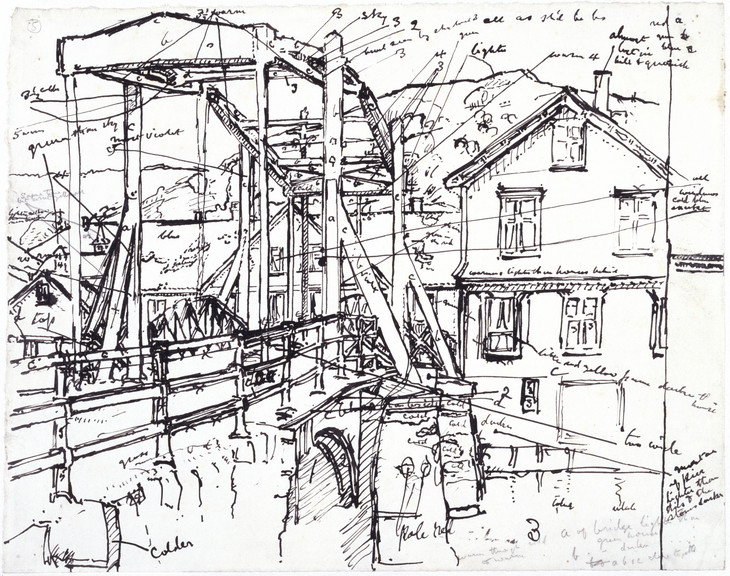

Gilman squared up the prepared canvas with a grid of drawn lines to transfer the design from a preparatory study (Tate T00026). The one-inch square grid was applied with a black graphic medium and runs continuously beneath the painted image. The lines of the grid have been marked off around the edges in a black liquid medium. The design was initially transferred in black pencil or Conté crayon, which was then reinforced with more freely drawn outlines in mauve oil paint. Colour was applied within these drawn shapes with equal certainty of purpose, each stroke of the brush remaining distinct. The paint was thick when applied, with apparently little addition of thinners or painting medium. Aeration created during vigorous mixing of the stiff artists’ oil colours on the palette is clearly visible under magnification as tiny bubbles in the paint. The brush was heavily loaded with paint and peaked impastos formed as it was drawn sharply away from the canvas at right angles. In some areas, particularly at the edges of more complex shapes, small areas of priming and drawing are left exposed, as Gilman strove not to cross his drawn boundaries. Most shapes are filled with several layers of paint as he modified colour values. This can be seen at the edges of the shapes, where the upper layers do not completely cover those underlying. In the area of the sky the paint is heavily re-worked using more fluid paints applied wet-in-wet, in directional strokes, which form horizontal rows of blues and greys with clouds in light tints. Drying cracks have formed where multiple layers of paint have been applied in relatively quick succession, and the paint has contracted at different rates. The painted surface remains unvarnished.

The notations of colour values in the study (Tate T00026) have been faithfully followed in the painting. Gilman retains careful control over the tonal value of the pure colours that he uses through a process of pre-selection, and the juxtaposition of near complementary colours to heighten their vibrancy. The colour mixtures used by Gilman are all opaque and most appear to contain some white, but pure white is never used on its own. Wyndham Lewis recalled that Gilman once said to him: ‘Thank God we are not “dirty” painters! You never use black, do you? Nor raw umber?’1 Indeed, no black is used. Like the impressionists, Gilman had rejected its use in painting. He appears also to have avoided the use of dark earth pigments. These characteristics are associated with developing a pure ‘spectral’ palette and identified with French impressionist technique from the late nineteenth century.

Roy Perry and Sarah Morgan

June 2005

How to cite

Roy Perry and Sarah Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', June 2005, in Robert Upstone, ‘Canal Bridge, Flekkefjord c.1913 by Harold Gilman’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background

Following the success of a trip to Sweden in 1912 which spurred him into a bout of creativity, the following year Gilman visited Norway and again produced a large number of pictures, both landscapes and urban scenes. He made another picture of Flekkefjord showing a street scene, which is now in a private collection.2

By comparison with most of the other Camden Town Group artists, Gilman travelled abroad quite widely. In 1894 he spent twelve months in Odessa as tutor to the children of an English family. After leaving the Slade, he went to Madrid for around a year in 1901–2, where he studied and copied Velázquez at the Prado, and where he also met and married his first wife, Grace Canedy. In 1905 they made a long visit to the United States to visit Grace’s family in Illinois and, in 1918, a few months before he died, Gilman went to Halifax, Nova Scotia, to make studies for Halifax Harbour at Sunset 1918 (National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa),3 a commission from the Canadian War Records Office. Gilman apparently considered an even more adventurous journey to find inspiration for his work. In an anecdote which is revealing both of his idealism and his initial admiration for the post-impressionist painter Paul Gauguin, Gilman reputedly put forward a proposal to his Camden Town Group colleagues that they should all go and live in the South Seas and have Arthur Clifton of the Carfax Gallery act as their agent in London. Reputedly, Spencer Gore quietly dissuaded Gilman.4

Gilman visited France on a number of occasions, and exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants from 1908 to 1910, and again in 1912 and 1913. In 1907 he stayed at Walter Sickert’s house at Neuville outside Dieppe and, most importantly, he visited Paris in late 1910 or early 1911 with his friends Charles Ginner and Frank Rutter in order to see impressionist and post-impressionist pictures. Ginner recalled how they looked at

collections such as Bernheim’s, who possessed a room entirely decorated with the works of Van Gogh, a sight unsurpassed in beauty and intensity; Durand Ruel’s collection of French Impressionists; Pellerin’s Cézannes; also the Vollard and Sagot Galleries with their Rousseaus, Picassos, Vuillards, etc.5

It was a cathartic experience for Gilman. His palette had already begun to brighten in pictures such as The Blue Blouse: Portrait of Elène Zompolides 1910 (Leeds City Art Gallery)6 and The Breakfast Table 1910 (Southampton Art Gallery).7 In part this may have been simply through exposure to the colourist tendencies already finding expression in the paintings of Gore, Ginner and Robert Bevan. But, as the art historian Andrew Causey has emphasised, another factor was the gathering repudiation of James Abbot McNeill Whistler’s belief in tonal painting and smooth surfaces,8 something that very much characterised the low-key harmony of Gilman’s paintings before 1910. Sickert, whom Gilman initially greatly respected, criticised Whistler repeatedly in print, and in 1910 published an outright and systematic rejection of his work in the Art News. This, Sickert wrote, was something he did ‘speaking for myself, and the very solid phalanx of young painters with whom I move ... To shrink from doing it would be misleading to the students I aspire to lead.’9

Influence

By the time Gilman painted Canal Bridge, Flekkefjord, he was an enthusiastic admirer of Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cézanne. Ginner recalled, however, that Gilman

did not immediately accept Van Gogh, and I can remember a long argument we had on the merits of this master. It was interesting to see that he slowly developed an intense admiration for Van Gogh, and came to look upon him as the greatest of the group of painters, Cézanne, Gauguin, etc., with which the Dutchman is associated. Gauguin, whom he at first believed in most, he considered too aesthetic and classic in spirit, though he always admired his amazing variety of design.10

Wyndham Lewis remembered of Gilman that

if you went into his room, you would find Van Gogh’s Letters at his table; you would see post cards of Van Gogh paintings beside favourites of his own hand. When he felt very pleased with a painting he had done latterly, he would hang it up in the neighbourhood of a photograph of a painting by Van Gogh.11

In addition to his admiration for van Gogh on aesthetic and artistic grounds, Rutter speculated that he identified with the Dutch artist on some more personal level, believing that

roughly handled by life, Gilman began to think for himself and take little or nothing on trust. In politics he became a Socialist with a profound dread and mistrust of society ... Van Gogh particularly appealed to him, partly because Gilman had a good deal of the Dutchman’s humanitarianism.12

Canal Bridge, Flekkefjord was clearly influenced by van Gogh, both in its vibrant palette and handling of paint. Most importantly, it appears also to refer to the several paintings van Gogh made of the Langlois Bridge at Arles,13 although Gilman’s composition does not directly copy any of them. Gilman might have known any of these pictures through reproductions, but the inspiration may have come from one in particular. It is likely he saw The Langlois Bridge (Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne)14 during his visit to Paris in 1910–11 when it was in the Bernheim Gallery, which Ginner recorded they visited.

Subject and ownership

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Study for 'Canal Bridge, Flekkefjord' c.1913

Ink on paper

support: 230 x 290 mm

Tate T00026

Purchased 1955

Fig.1

Harold Gilman

Study for 'Canal Bridge, Flekkefjord' c.1913

Tate T00026

Gilman moved to the new town of Letchworth Garden City sometime around 1908. His neighbour was Stanley Parker, the brother of Barry Parker of Parker and Unwin, the architects who developed the town. Stanley’s wife Signe (née Bergström) was Swedish, and it may have been as a result of their conversations that Gilman was inspired in 1912 to visit Sweden. Signe’s brother had bought an estate at Sundsholm in south-eastern Sweden, and when the Parkers visited him in 1913, along with William Ratcliffe, it is possible Gilman came too before moving on to Norway.16 The bridge at Flekkefjord dates from 1838, and had changed little when Gilman painted it. But in 1936 it was rebuilt and now looks very different.17 The brightly painted houses were not an invention by the artist, but an accurate account of how the town looked at this time.18

The picture’s first owner was the painter Walter Taylor (1860–1943), a founder member of the London Group and collector of a number of Gilman’s pictures including Leeds Market (Tate N04273). He accumulated a notable group of early modern French and British paintings, owning works by Henri Matisse, Pierre Bonnard, Edouard Vuillard, Raoul Dufy, Matthew Smith, Stanley Spencer and Mark Gertler. Canal Bridge, Flekkefjord was the first picture by Gilman to enter a public collection when it was bought by the Tate Gallery in 1922.

Robert Upstone

May 2009

Notes

Reproduced in The Painters of Camden Town 1905–1920, exhibition catalogue, Christie’s, London 1988 (128, as ‘Swedish or Norwegian Landscape’).

See Andrew Causey, ‘Harold Gilman: An Englishman and Post-Impressionism’, in Harold Gilman 1876–1919, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, London 1981, pp.12–13.

Charles Ginner, ‘Harold Gilman: An Appreciation’, in Memorial Exhibition of Works by the Late Harold Gilman, exhibition catalogue, Leicester Galleries, London 1919, p.5.

Reproduced in Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.143.

Walter Sickert, ‘Abjuro’, Art News, 3 February 1910, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Richard Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford 2000, p.193.

Frank Rutter, ‘The Work of Harold Gilman and Spencer Gore: A Definitive Study’, Studio, vol.101, March 1931, p.207.

See J.-B. de la Faille, The Works of Vincent Van Gogh: His Paintings and Drawings, Amsterdam 1970, nos.397, 400, 570–1.

See Roy A. Perry, ‘Harold Gilman: Canal Bridge, Flekkefjord’, in Stephen Hackney (ed.), Completing the Picture: The Materials and Techniques of Twenty-Six Paintings in the Tate Gallery, London 1982, p.79.

Carl Hambro, Cultural Attaché, Royal Norwegian Embassy, letter to Tate Gallery, 9 April 1956, Tate Catalogue file.

Related biographies

Related essays

- Walter Sickert’s Drawing Practice and the Camden Town Ethos Alistair Smith

- The Evolution of Painting Technique among Camden Town Group Artists Stephen Hackney

Related catalogue entries

Related reviews and articles

- Charles Ginner, ‘Harold Gilman: An Appreciation’ in Memorial Exhibition of Works by the Late Harold Gilman, exhibition catalogue, Ernest Brown & Phillips, The Leicester Galleries, London, October 1919, pp.3–8.

- Louis F. Fergusson, ‘Harold Gilman’ in Wyndham Lewis and Louis F. Fergusson, Harold Gilman: An Appreciation, London: Chatto & Windus 1919, pp.19–32.

How to cite

Robert Upstone, ‘Canal Bridge, Flekkefjord c.1913 by Harold Gilman’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www