Walter Richard Sickert Sir Alec Martin, KBE 1935

Walter Richard Sickert,

Sir Alec Martin, KBE

1935

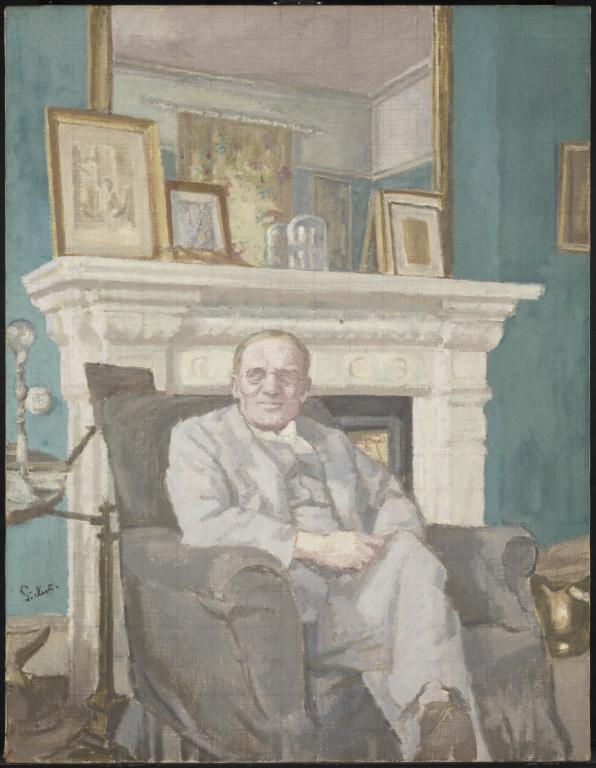

This portrait of Sir Alec Martin in Sickert’s home in St Peter’s-in-Thanet, near Broadstairs in Kent, was developed in a series of sittings. A reference photograph might also have been snapped by Sickert’s wife Thérèse. Martin is seated in a blue armchair, cross-legged, wearing a pale grey waistcoat and suit. Although his head is turned to face the viewer, the fall of light casts the eyes, behind spectacle lenses, in shadow, resulting in an unreadable, dispassionate expression. Life-long friends, Martin commissioned a series of family portraits (Tate T00222 and T00223) from Sickert to provide the artist with additional income in late life, from which this remarkably empirical representation arose.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Sir Alec Martin, KBE

1935

Oil paint on canvas

1397 x 1079 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Sickert’ in black paint bottom left

Presented by Sir Alec Martin, K.B.E., through the National Art Collections Fund 1958

T00221

1935

Oil paint on canvas

1397 x 1079 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Sickert’ in black paint bottom left

Presented by Sir Alec Martin, K.B.E., through the National Art Collections Fund 1958

T00221

Ownership history

Commissioned from the artist by Sir Alec Martin 1935, by whom presented through the National Art Collections Fund to Tate Gallery 1958.

Exhibition history

1981–2

Late Sickert: Paintings 1927–1942, (Arts Council tour), Hayward Gallery, London, November 1981–January 1982, Sainsbury Centre for the Visual Arts, University of East Anglia, Norwich, March–April 1982, Wolverhampton Art Gallery, April–May 1982 (23, reproduced).

1986

Sickert and Thanet: Paintings and Drawings by W.R. Sickert 1860–1942, Ramsgate Library Gallery, Kent, October–November 1986 (14).

1989–90

W.R. Sickert: Drawings and Paintings 1890–1942, Tate Gallery, Liverpool, March 1989–February 1990, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1990 (38, reproduced).

References

1960

National Art Collections Fund Fifty-Sixth Annual Report 1959, London 1960, p.21.

1960

Lillian Browse, Sickert, London 1960, p.103.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, p.639.

1967

David Sylvester, ‘Walter Sickert: More about the Englishness of English Art’, Artforum, vol.5, no.9, May 1967, p.45, reproduced p.44.

1973

Wendy Baron, Sickert, London and New York 1973, pp.171, 174, no.415.

1975

Richard Morphet, ‘The Modernity of Late Sickert’, Studio International, vol.190, no.976, July–August 1975, pp.35–6, reproduced.

1988

Richard Shone, Sickert, Oxford 1988, p.95, reproduced pl.75.

1992

Wendy Baron and Richard Shone (eds.), Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992, p.324, reproduced fig.224.

2006

Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.719, pp.119, 537, reproduced.

Technique and condition

Walter Sickert chose the same supports for the portraits of Sir Alec Martin and Lady Martin (Tate T00222), suggesting that they were prepared at the same time. The canvas is a coarse open-weave cloth, probably jute, supplied pre-primed and stretched by the artists’ colourmen Newman. The cloth is sized and primed with a lean white ground, providing a slightly absorbent preparatory surface with a rough texture.

Sickert has used the same basic painting technique for both portraits. He initially drew with a brush in black paint directly onto the lean white ground to establish the outlines of his composition, perhaps working from life. This was followed by a first painting to lay-in a camaieu-type preparation using selected colours each in a range of two tones, consisting of pure pigment and the same pigment mixed with white on his palette. He applied a black grid on top of this first painting, perhaps using a ‘grille’ (see Tate N04673) and working with a squared-up image, in this case probably a photograph. This enabled him to work freely building up the tonal composition and using the squared-up image as a fixed point of reference that he could refer back to but which did not limit him. He explained in a letter to his friend Ethel Sands:

when you are really painting (as opposed to merely colouring a drawing) you must be absolutely free to find your scale as you go & incessantly to modify it by expansion or contraction without being cramped by a set design ... To paint, as you know & as you practice, is to fling side by side some patches of related tones & eventually trim them by expansion & contraction into shape, & to this a set outline design is hostile & hampering.1

The paint appears lean and is probably all oil-based, squeezed from the tube onto his palette where it was mixed and worked. There is no modification to the composition, perhaps because Sickert was facilitated by the photographic image but also because the portrait was carefully planned so that it could be quickly achieved. The lights are applied using white or near-white paint and not simply exposed ground, as they are in the portrait of Lady Martin, and it is likely that this painting went through the same stages but was then worked on for longer with separate regime for the lights, like that of the portrait of his son (see Tate T00223). All three works are unvarnished reflecting Sickert’s preference for unvarnished surfaces at this time.

Stephen Hackney

November 2005

Notes

How to cite

Stephen Hackney, 'Technique and Condition', November 2005, in Nicola Moorby, ‘Sir Alec Martin, KBE 1935 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, January 2006, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Subject

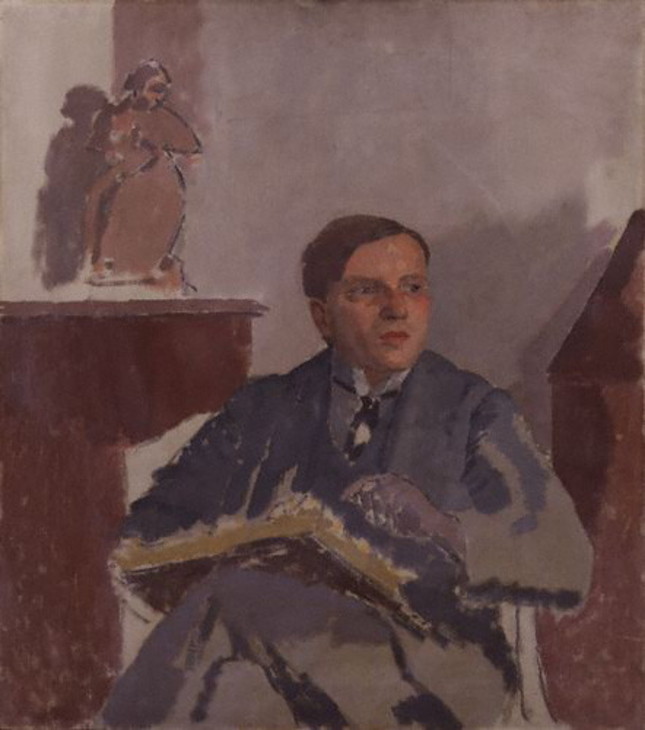

In 1935 Sir Alec Martin (1884–1971) commissioned Walter Sickert to paint portraits of himself, his wife Ada, Lady Martin, and their youngest son, Claude. Martin later admitted: ‘We treated the whole thing as a bit of fun. I wasn’t really expecting a great deal from him.’1 However, the seventy-five-year-old Sickert astounded him by producing three significant portraits, which justified and confirmed his reputation as one of Britain’s greatest living artists (see also Tate T00222 and T00223, figs.1 and 2).

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Lady Martin 1935

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1397 x 1079 mm

Tate T00222

Presented by Sir Alec Martin KBE through the Art Fund 1958

© Tate

Fig.1

Walter Richard Sickert

Lady Martin 1935

Tate T00222

© Tate

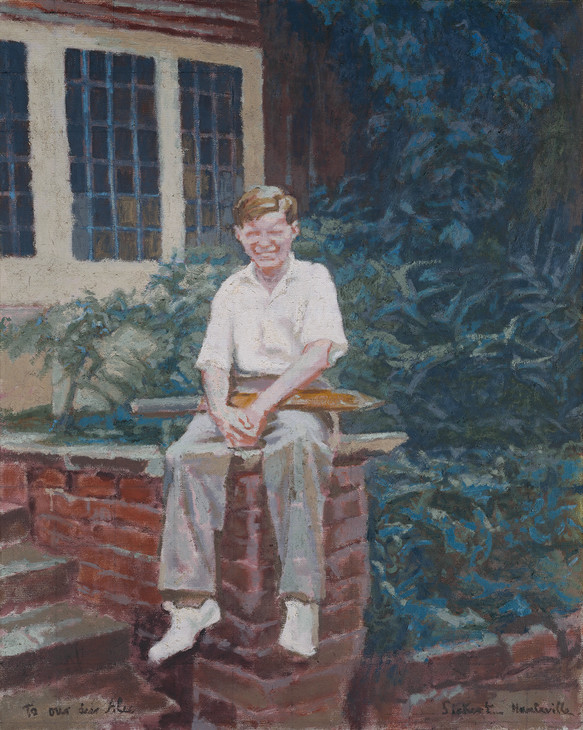

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Claude Phillip Martin 1935

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1270 x 1016 mm

Tate T00223

Presented by Sir Alec Martin KBE through the Art Fund 1958

© Tate

Fig.2

Walter Richard Sickert

Claude Phillip Martin 1935

Tate T00223

© Tate

Sickert’s portrait of the fifty-one-year-old Martin depicts him wearing a light grey suit with a waistcoat and jacket sitting cross-legged in a blue armchair with his head slightly turned to his right in order to face the viewer. The interior shown in the background is one of the rooms at Hauteville, Sickert’s house at St Peter’s-in-Thanet, near Broadstairs in Kent.2 Martin is seated in front of a large fireplace and beside his chair on a side table on the right there is a structure made of wood and metal, possibly a reading stand, and the base and bulb of an electric lamp without a shade. The assortment of items arranged along the mantelpiece, such as the gilt-framed mirror, the paintings and prints, and the domed glass bell-jar, are typical of the type of domestic interior Sickert had become famous for painting. The framed painting partially visible on the wall on the right-hand side appears to be the same long landscape-format picture fully apparent in the portrait of Lady Martin (Tate T00222).

Sir Alec Martin

John Laviers Wheatley 1892–1955

Sir Alec Martin 1920s or 1930s?

Oil paint on canvas

914 x 813 mm

National Portrait Gallery, London

© reserved

Photo © National Portrait Gallery, London

Fig.3

John Laviers Wheatley

Sir Alec Martin 1920s or 1930s?

National Portrait Gallery, London

© reserved

Photo © National Portrait Gallery, London

Martin certainly acted as a ‘good and faithful friend’ to Sickert. The two men were introduced by the collector, Hugh Lane (1875–1915), in around 1899 when Martin was only fifteen years old and Sickert was approaching forty and just divorced from his first wife.5 In his recorded reminiscences for the BBC in 1961, Martin described his lifelong friendship with Sickert as ‘one of the landmarks of one’s life to have known him and be in his inner circle of friendship’.6 They shared many interests in addition to art, including the music hall and swimming in the Serpentine.7 Martin respected Sickert as one of Britain’s greatest living artists, but also recognised his vulnerability in old age and frequently took practical steps to alleviate Sickert’s money worries. He remained a trusted friend and adviser for many years, attending Sickert’s eightieth birthday tea party in 1940.8 He is recorded as present at Sickert’s funeral in St-Martin-in-the-Fields in 1940 and continued to look after the artist’s posthumous interests as sole executor of his will.

Sickert’s lack of financial acumen characterised his dealings as a professional artist throughout his life. He was apt, for example, to waste money unnecessarily and to charge too little for his works. His improvident behaviour particularly worried and frustrated his friends who attempted to instil in him the need for economy and saving, for his wife’s sake as much as his own. In 1934 Sickert’s debts had become awkward enough for him to approach Martin at Christie’s with a view to selling some engravings for ready cash. Martin recognised Sickert’s situation was far more serious and was moved to do something for him. With Sylvia Gosse, Gerald Kelly and John Cooper he formed a committee, and in May petitioned a number of supporters and admirers asking them to contribute to a fund. The list of benefactors to the fund numbered over two hundred names and included celebrities from the art world such as Clive Bell, Philip Wilson Steer and William Rothenstein, old friends such as Walter Taylor, Ethel Sands and Nan Hudson, former students such as Winston Churchill and Lord Methuen, and admirers and patrons like Lord Henry Cavendish-Bentinck, Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies and Peggy Ashcroft. Not everyone they approached was sympathetic, however. Henry Tonks wrote to the critic D.S. MacColl:

I do not know if [Charles] Aitken [former Director of the Tate Gallery] spoke to you about Sickert’s condition if he did he probably told you he wished to have nothing to do with a scheme for keeping him. I do not blame him. On the other hand there are a certain number who recognize how many foolish things he has done yet hate to think of a man of his eminence coming near to starving. I know you must not put your hand in your pocket as you have been good enough to take me in your confidence on these matters but I thought if the opportunity came up you might be able to influence somebody who is interested in Sickert as an artist and might like to help him.9

Charles Aitken seems to have been in the minority, however. Martin’s efforts raised £2,050, a sum which erased Sickert’s debts and left funds to spare. A trust was established to meter out the remaining money in regular instalments, a measure designed to prevent it being frittered away. Sickert wrote to Martin to thank him for:

stretching forth such an efficient & strong hand to pull me out of the water ... I am rather surprised not to feel more shame than I do at being caught guilty of some mismanagement. It is evident however that the friends whose names I have on your list confirm me in my opinion that they must all be convinced of a measure of approbation of my painting and teaching. They have handed me the sort of approbation which lies at the bottom of a civil list. My dearly loved wife who has had to bear the brunt of my difficulties takes the same view. Please express to my friends, our common gratitude – Je ne recommencerai pas.10

Martin continued to try to find ways of supporting Sickert during the 1930s. He persuaded the artist to spend the summer in Margate, close to the Martins’ house at Broadstairs, a move which suited Sickert so well that he decided to stay on and rented a house in the nearby village of St-Peter’s-in-Thanet. The house was called ‘Hopeville’, although Sickert soon changed this to ‘Hauteville’. The commission for portraits of the Martin family was clearly also intended as another way of providing Sickert with some additional income.

Photography

Dennis Farr in the catalogue entry for the 1964 Tate Gallery catalogue noted the existence of a squared-up photograph of Sickert standing against part of the same background of the two portraits.11 Sickert’s preferred method for painting portraits had been to rely solely on photographic sources. As he explained after completing his portrait of Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies in 1932 (Tate N04673), he had no desire to paint directly from the subject since the demanding nature of the experience for the sitter was not conducive to great portraiture.12 Besides, he told Ffrangcon-Davies, ‘I know your face so well I don’t have to have you before me to paint you’.13

However, it appears that in later years Sickert may have combined the use of photographs with an occasional return to direct observation of his model. His last portrait, Mrs Anna Knight (Tate N06142), for example, seems to have been painted directly in front of the subject. In a letter to the Tate Gallery in 1958, Alec Martin recorded that he clearly remembered sitting to the artist in one of the rooms of Hauteville but, unlike his wife and son, he did not recall a photograph having been taken of him.14 The composition of the painting seems to confirm a photographic source since it favours the cropping of the body in favour of the upward view of the fireplace. It seems likely therefore that, in common with the rest of his family, a reference snapshot was taken of Martin by Thérèse Lessore without his being aware of it, but it also seems that Sickert used his time with the sitter to make useful sketches which also informed the painting process. A small pencil sketch of the head of Sir Alec Martin was sold at Christie’s in 1987.15

Reception

In the later decades of the twentieth century, art historians begun to re-evaluate Sickert’s late work. David Sylvester and Richard Morphet both wrote key polemical essays reconsidering Sickert’s late photograph-based work with reference to developments in British figurative painting and pop art. Morphet, for example, compared the size, appearance and composition of Sickert’s portrait of Sir Alec Martin to Francis Bacon’s series of paintings of seated figures.16 Like Sickert, Bacon (1909–1992) complicated interior spaces with mirrored reflections, pictures within pictures and oppressive furnishings. Morphet describes the figure of Martin as being visually enclosed both by the furniture and the visible gridlines of Sickert’s squaring-up: ‘Taken with the box-like enclosed space created by the mirror, these make a not too distant, even if unintentional, parallel with the curtains and boxes by which Bacon’s seated figures are often enclosed. The raw directness of paint application is a further obvious parallel.’17

David Sylvester, who had a long association with Bacon, also drew parallels between the two artists, comparing their liking for ‘strange shapes, queer misshapen shapes’.18 Writing about Sickert’s portraits of Sir Alec and Lady Martin, he argued that:

These figures are no more than presences: they haven’t been built up into characters; there is no more of them there on canvas than they would manifest of themselves if we came into a room and saw them sitting there. No more but also no less: they are very much there – solidly there, and yet they are mere shades of figures, have none of the corporeal substance which we know human figures to have ... Sickert, painting the Martins from photographs, had the boldness to leave unexplained and made no pretence of explaining those forms which did not explain themselves to the camera’s eye, adding nothing not given to the eye. These portraits simply reflect back at us a sensation of the sitters sitting there, a sensation of their there-ness ... The Sickert of the Martin portraits has a Velásquez-like acceptance of what appears to the eye. The figures look as they look in Northern daylight coming through a window. This is life as one would see it if one had no feelings, no thoughts, no moral or esthetic prejudices. And these portraits are like demonstrations that life seen like this is life as it is. They have an empiricism as ruthless, as disenchanted, as raw, as absolute, as the empiricism of Hume.19

Even during his own lifetime, commentators identified an absence of empathy on Sickert’s part with the subjects he chose to paint. Despite identifying scenes with an emotive or dramatic potential, Sickert remains at all times a dispassionate observer. All three Martin portraits display this characteristic detachment. Very little of the personality of the sitters is revealed from the way they have been portrayed. Alec Martin was a highly successful and intelligent man and someone whom Sickert counted as a friend and supporter. Given his recent indebtedness to Martin, the artist might, for example, have chosen to depict him as a discerning connoisseur or a kindly philanthropist, yet almost nothing of the sitter’s personal or professional traits are apparent within his portrait. The fall of light on Martin’s face veils his eyes behind their glasses in shadow and renders his face strangely blank and unreadable. It was not until the late 1960s and 1970s that the existential quality of Sickert’s work was appreciated and interpreted.

Nicola Moorby

January 2006

Notes

Sir Alec Martin, Walter Sickert 1860–1942: Sketch for a Portrait, 10 February 1961, BBC Home Service, LP 26657, side 1.

Photograph of Sickert’s eightieth tea party, reproduced in Sylvia Gosse 1881–1968: Paintings and Prints, exhibition catalogue, Parkin Gallery, London 1989, [p.15].

Henry Tonks, letter to D.S. MacColl, 5 April 1934, MacColl Archive T347, Glasgow University Library.

Walter Sickert, letter to Alec Martin, copied to J.B. Manson, 29 October 1934, Tate Archive TGA 806/1/604–9.

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, p.639.

Christie’s, London, 30 July 1987 (lot 206); Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.719.1.

Richard Morphet, ‘The Modernity of Late Sickert’, Studio International, vol.190, no.976, July–August 1975, p.35, reproduced.

Related biographies

Related essays

- After Camden Town: Sickert’s Legacy since 1930 Martin Hammer

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Sir Alec Martin, KBE 1935 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, January 2006, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www