Walter Richard Sickert The Servant of Abraham 1929

Walter Richard Sickert,

The Servant of Abraham

1929

This small-scale canvas is compositionally dominated by a disembodied head, rendered in broad strokes of dull brown and tilted at a dramatic angle. The picture’s source was a photograph of the sixty-nine-year-old Walter Sickert taken by his third wife, Thérèse Lessore, here translated into an ambiguously grim expression in paint emphasised by the glowing square-cut beard and cryptic title. It is one of three late self-portraits casting the artist as a Biblical character, appropriating the monumentality of the Old Masters as well as provoking public perception of Sickert in the national press at the time. The Manchester Guardian named it a ‘terrific statement of an artist ego’.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Servant of Abraham

1929

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 508 mm

Inscribed by the artist in brown paint ‘Sickert’ top right and ‘The Servant of Abraham’ bottom left

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1959

T00259

1929

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 508 mm

Inscribed by the artist in brown paint ‘Sickert’ top right and ‘The Servant of Abraham’ bottom left

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1959

T00259

Ownership history

Bought from the artist through the Savile Gallery, London, by the artist’s brother-in-law Major Frederick Lessore; by descent to Mrs Helen Lessore; purchased from the Beaux Arts Gallery, London, June 1959, by the Friends of the Tate Gallery out of funds provided by Associated Television Ltd and presented to Tate Gallery.

Exhibition history

1930

Paintings by R. Sickert, A.R.A., Savile Gallery, London, February 1930 (28, reproduced on front cover).

1932

Paintings by Richard Sickert, A.R.A., Beaux Arts Gallery, London, April–May 1932 (22).

1938

Exhibition of Pictures Suitable for Public Galleries and Important Collections, Beaux Arts Gallery, London, June 1938 (18).

1949

Paintings and Drawings by Walter Richard Sickert, Beaux Arts Gallery, London, May–June 1949 (2).

1953

Paintings by Sickert, Beaux Arts Gallery, London, September–October 1953 (15).

1957

A Selection of Important Works Suitable for Galleries, Beaux Arts Gallery, London, 1957 (1, reproduced).

1960

Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, (Arts Council tour), Tate Gallery, London, May–June 1960, Southampton Art Gallery, July 1960, Bradford City Art Gallery, July–August 1960 (173, reproduced).

1968

Helen Lessore and the Beaux Arts Gallery, Marlborough Fine Art, London, February 1968 (49, reproduced).

1973

Sickert, Fine Art Society, London, May–June 1973, Fine Art Society, Edinburgh, June–July 1973 (85, reproduced).

1977–8

Sickert, (Arts Council tour), Ferens Art Gallery, Hull, December 1977–January 1978, Glasgow Art Gallery, February–March 1978, Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery, April–May 1978 (58, reproduced pp.2, 32).

1981–2

Late Sickert: Paintings 1927 to 1942, (Arts Council tour), Hayward Gallery, London, November 1981–January 1982, Sainsbury Centre for the Visual Arts, University of East Anglia, Norwich, March–April 1982, Wolverhampton Art Gallery, April–May 1982 (2, reproduced on front cover).

1989–90

W.R. Sickert: Drawings and Paintings 1890–1942, Tate Gallery, Liverpool, March 1989–February 1990, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1990 (32, reproduced).

1992–3

Sickert: Paintings, Royal Academy, London, November 1992–February 1993, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, February–May 1993 (104, reproduced).

1998

James McNeill Whistler, Walter Richard Sickert, Fundación ‘La Caixa’, Madrid, March–May 1998, Museo de Bellas Artes, Bilbao, May–July 1998 (88, reproduced).

2004

Walter Richard Sickert: The Human Canvas, Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, July–October 2004 (38, reproduced).

2010

The Art of Walter Sickert, The Lightbox, Woking, May–July 2010 (no catalogue).

References

1930

T.W. Earp, ‘The Work of Richard Sickert, A.R.A.’, Apollo, vol.11, May 1930, p.297, reproduced p.227.

1930

Alfred Thornton, ‘Walter Richard Sickert’, Artwork, vol.6, no.21, Spring 1930, p.16, reproduced p.17.

1947

Osbert Sitwell (ed.), A Free House! Or the Artist as Craftsman: Being the Writings of Walter Richard Sickert, London 1947, reproduced on frontispiece.

1959

Michael Nightingale, ‘After Worthing: Industrial Patronage’, Museums Journal, vol.59, no.4, July 1959, p.86, reproduced pl.4.

1960

Lillian Browse, Sickert, London 1960, pp.22, 41, 50, 102, no.96, reproduced pl.96.

1961

John Rothenstein, Sickert, London 1961, pp.5, [32], reproduced p.1.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, p.640.

1972

Anthony Powell, ‘Book Reviews: The Servant of Abraham’, Apollo, vol.95, no.121, March 1972, p.226.

1973

Wendy Baron, Sickert, London and New York 1973, pp.169, 171, no.405, reproduced fig.283.

1976

Denys Sutton, Walter Sickert: A Biography, London 1976, p.233, reproduced fig.40.

1988

Richard Shone, Sickert, Oxford 1988, p.124, reproduced pl.72.

1990

Robert Hughes, Frank Auerbach, London 1990, p.87.

1990

Jean Overton Fuller, Sickert and the Ripper Crimes, Oxford 1990, pp.72–5, reproduced (between pp.96–7).

1995

Stella Tillyard, ‘The End of Victorian Art: W.R. Sickert and the Defence of Illustrative Painting’, in Brian Allen (ed.), Towards a Modern Art World, New Haven and London 1995, p.200.

2001

David Peters Corbett, Walter Sickert, London 2001, pp.66–7, reproduced fig.56.

2001

James Hyman, The Battle for Realism: Figurative Art in Britain During the Cold War 1945–1960, New Haven and London 2001, pp.122, 224 n.138, reproduced fig.125.

2002

Patricia Cornwell, Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper – Case Closed, London 2002, p.298.

2004

Alistair Smith (ed.), Walter Sickert: ‘drawing is the thing’, exhibition catalogue, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester 2004, p.2.

2005

Matthew Sturgis, Walter Sickert: A Life, London 2005, pp.570, 575.

2006

Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.696, pp.117, 141, 526–7, reproduced.

Technique and condition

The Servant of Abraham is painted on a very coarse-weave canvas with a white commercial primer, which is probably oil-based. The cloth has a very open weave that provided a highly textured and quite absorbent preparatory surface, as the fluid primer flowed into the weave interstices and only thinly covered the canvas tops. It is very similar to that used for The Seducer (Tate T05529) and Variation on Peggy (Tate T06601) and may also have been purchased from L. Cornelissen & Son, although there is no stamp on this canvas.

Sickert has applied a camaieu (see Tate N05089) by washing the white ground with a green scumble over the background and a pink scumble under the face. Areas of shadow such as the face against the light are in green; this paint is lean and brushed with crisp impasto. He probably left this paint to dry and then continued with broad brushstrokes using duller browns and greens to apply local colour and details using a richer medium and brushing impasto from a loaded brush, some of which has slumped before drying. Other areas have crisper impasto and were possibly applied at tube consistency, after mixing on a palette. The ground is largely covered, brushing close to the paint boundaries. There are black drawing lines, which are dry and powdery, perhaps made using a charcoal or black chalk, on top of the paint to strengthen the image.

The painting was left unvarnished and put into its frame while still wet, so that the rebate has impressed into the surface and there are small pieces of gilding in the paint. The surface is quite glossy and the varnish very thin; it may have been applied later as a retouching varnishing for display.

Stephen Hackney

November 2004

How to cite

Stephen Hackney, 'Technique and Condition', November 2004, in Nicola Moorby, ‘The Servant of Abraham 1929 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, July 2005, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background and subject

The Servant of Abraham is one of a trio of important late pictures in which Walter Sickert combined self-portraiture with the persona of a Biblical character. Painted at the artist’s studio at 1 Highbury Place, Islington,1 it was first exhibited at the Savile Gallery, London, in 1930 where it was shown in conjunction with another self-portrait, Lazarus Breaks his Fast c.1927 (Estorick Collection, London).2 The culmination of the series was the large painting, The Raising of Lazarus c.1929 (fig.5),3 first exhibited at the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition in 1932.

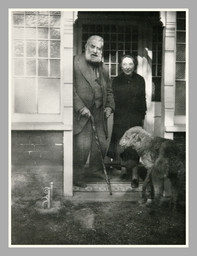

Thérèse Lessore 1884–1945

Squared-up Photograph of Walter Richard Sickert c.1929

Islington Local History Centre, London

© Estate of Thérèse Lessore

Photo © Islington Local History Centre

Fig.1

Thérèse Lessore

Squared-up Photograph of Walter Richard Sickert c.1929

Islington Local History Centre, London

© Estate of Thérèse Lessore

Photo © Islington Local History Centre

According to the Old Testament, the servant of Abraham was sent from Canaan to find a wife for his master’s son, Isaac, among Abraham’s people in Mesopotamia. Guided by God, the servant made his way to the town of Nahor and found Rebekah, a woman from Abraham’s family, drawing water from the well. She returned with him to Canaan and married Isaac and through their union God’s covenant with Abraham was fulfilled.5 Historically, the episode has been a theme for paintings of religious subjects, for example, Rebecca and Eliezar c.1650 (Museo del Prado, Madrid), by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617–1682) and Eliezer et Rebecca 1648 (Louvre, Paris),6 by Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665). The Book of Genesis records the name of the servant of Abraham as Eliezer of Damascus, a Gentile.7 He is portrayed as a man of intelligence and loyalty whom Abraham had made the steward of his household and at one point considered making his heir. Yet in the Bible his name is only used once and at all other times he is known simply as the ‘servant of Abraham’. His independent identity is subsumed within his complete devotion to his master, an example which has become a paradigm for selfless devotion to God. As a metaphor, however, the character can also be seen to represent a sense of identity that is problematic, uncertain or contradictory.

As a young man Sickert had trained as an actor and his love of assuming a role persisted throughout his life. He painted self-portraits intermittently through his career, using them as a vehicle by which to portray various aspects of his character, rather than merely recording the superficial changes of his physical appearance. For example, the struggling artist depicted in The Juvenile Lead 1907 (fig.2),8 is a different figure from that of the defiant eccentric in Self-Portrait: The Bust of Tom Sayers 1913 (fig.3).9 The greatest concentration of self-portraits was executed during the last fifteen years of his life when he adopted a variety of appropriate character roles, deliberately playing up his advancing years. His association with ‘The Servant of Abraham’, however, is harder to interpret. The role is representative of ambiguous self-expression and Sickert is therefore making a comment on the nature of identity itself.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Juvenile Lead (Self-Portrait) 1907

Oil paint on canvas

458 x 510 mm

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.2

Walter Richard Sickert

The Juvenile Lead (Self-Portrait) 1907

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Self-Portrait: The Bust of Tom Sayers 1913

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 503 mm

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Fig.3

Walter Richard Sickert

Self-Portrait: The Bust of Tom Sayers 1913

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Reception

Following its first exhibition at the Savile Gallery in 1930, various interpretations of The Servant of Abraham were offered in the newspapers. The critic of the Manchester Guardian saw the painting as a defiant statement, both technically and metaphorically reinforcing Sickert’s artistic powers:

The arrogant bearded face is painted with tremendous summary force, with something of the fierceness of a bird in its expression. Nowhere has he shown more conclusively his mastery of his material and complete understanding of exactly what he wants to do. It is like sculpture in the elimination of everything that does not finely contribute to a foreseen end ... In this age of synthetic art, where the forcible-feeble so flourishes, this terrific statement of an artist ego must stand as one of the marking pictures of our time. One would like to see it in the Uffizi beside the other self-portraits of famous artists.10

The Morning Post, however, thought that the portrait was a ‘problematic mask’ that posed a direct challenge to the viewer:

Anyone who would solve the enigma known nowadays as Richard Sickert, A.R.A., must see his self-portrait ‘The Servant of Abraham’ as subscribed on the canvas itself, with his customary blague. The left eye, looking as purposely as the point of a fencing foil, arrests you as soon as you enter the Savile Gallery ... and the right eye, half shut in the shade, sardonically directs the attack on the intellectuality or humour of the visitor. The shaggy face cannot be read as easily as a tale with a happy ending. There is in it, as in his art, something that gives you seriously to think.11

The artist Walter Bayes, writing in the Saturday Review, described the work as:

A cruel caricature, following on the previous discovery that by stressing the character of the ‘man who understands the commercial side of Art’ which he frequently affects, he could turn himself into a rather formidable Jew. The portrait is an excellent rendering of one of his favourite impersonations; but it is not, of course, in the least like the real Sickert, the delicacy of whose expression that impersonation never for long concedes.12

Bayes believed that the persona adopted in the painting was a fictional conceit, rather than an insight into the artist’s inner soul. Later commentators have been inclined to view the work as possessing a deeper, subconscious, psychological message. Wendy Baron has interpreted it as an acknowledgement that, like the servant of Abraham, Sickert too was ‘an instrument of divine will, but to aesthetic rather than spiritual ends’.13 David Peters Corbett has described the face as a ‘badge of suffering’, symbolic of a man who has forfeited his pre-eminence and no longer occupies the position he once commanded.14 He sees the painting as an act of self-questioning by Sickert of his career and achievements at a time when he could no longer be considered to be at the centre stage of artistic development.

The ambiguous nature of The Servant of Abraham and the potential for multiple readings is a deliberate strategy, typical both of Sickert’s personality and his art. He had always proved a problematic artist for critics to categorise owing to his apparent refusal to conform within the frameworks of available artistic movements and his tendency towards self-contradiction. From the early 1920s, however, particularly after he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy, Sickert’s own identity became the subject of much discussion in the press. At a late stage in his career the national newspapers began to take affectionate pride in one of the few artists whose work was recognised and admired on the continent, and this recognition was accompanied by an acceptance, even a celebration, of his unconventional nature. He began to be feted not only as a significant artist, but also as something of a local London celebrity, with his movements, witticisms and sartorial peculiarities regularly reported in the papers. Sickert, unlike his more reticent and bashful colleague Philip Wilson Steer, made good copy.15

Particularly alluring to the press was his abandonment of the name ‘Walter Richard Sickert’ in around 1925–7, in favour of the terser ‘Richard Sickert’. ‘Few artists ... are more ready to change their names, their beard, and the titles of their pictures’, noted the Daily Express in 1929.16 Words frequently used to describe him, such as ‘irrepressible’, ‘protean’ and ‘eccentric’, testify to the emerging sense of a Sickertian myth. As an avid reader of the newspapers and a subscriber to a press cuttings service, Sickert would have been well aware of the public’s fascination with him. He relished the attention and played up shamelessly to the part of an ageing eccentric, choosing roles which vindicated certain aspects of his behaviour. The late self-portraits, including The Servant of Abraham, demonstrate a conscious engagement with his own public perception at a time when the mythologising process was underway in the national press. This engagement is simultaneously humorous, perceptive, provocative and serious.

Biblical self-portraits

Richard Shone has discussed the numerous other roles Sickert projected in his late self-portraits.17 These include the dignified gentleman of The Rural Dean c.1932 (private collection), A Domestic Bully c.1935–8 (Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh), the frail, disillusioned figure in Self-Portrait in Grisaille c.1935 (National Portrait Gallery, London),18 the mischievous but harmless rascal sneaking some bottles of wine in Home Life 1937 (private collection),19 and The Invalid c.1939–40 (private collection).20 The three Biblical self-portraits of 1927–9 present a patriarchal image of the artist. This notion may have suggested itself to Sickert because of his current fashion for wearing a full, square-cut beard, a fad that gave him something of the air of a generic Old Testament character. He may even have been inspired by a particular image. Rebecca and Abraham’s Servant at the Well, exhibited 1833 (Tate N00338, fig.4), by William Hilton the Younger (1786–1839), was one of a large number of British paintings bequeathed to the nation by Robert Vernon in 1847 and could have been seen by Sickert at the Tate Gallery. The bearded profile of the figure of the servant resembles the artist’s own appearance at this time.

William Hilton the Younger 1786–1839

Rebecca and Abraham's Servant at the Well exhibited 1833

Oil on canvas

support: 864 x 1105 mm; frame: 1190 x 1420 x 120 mm

Tate N00338

Presented by Robert Vernon 1847

Fig.4

William Hilton the Younger

Rebecca and Abraham's Servant at the Well exhibited 1833

Tate N00338

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Raising of Lazarus c.1929

Oil paint on canvas

2442 x 912 mm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Felton Bequest, 1947

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Fig.5

Walter Richard Sickert

The Raising of Lazarus c.1929

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Felton Bequest, 1947

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

The three Biblical paintings are powerful independent images, but a certain dialogue also exists across them, chronicling the artist’s obsession with his own public image. In Lazarus Breaks his Fast an unkempt and vulnerable-looking Sickert tucks into a plate of food with a napkin tied around his neck. The role of Lazarus, a man raised from the dead by Jesus, may represent a celebration of Sickert’s recovery after a long and serious illness,21 but may also be an oblique reference to his self-reinvention around this period with a new name. While The Servant of Abraham presents a problematic view of an identity in crisis, the culmination of the series, The Raising of Lazarus c.1929 (fig.5), posits the artist in the role of God or Christ, tenderly laying his hands on the shrouded body of the dead Lazarus. This represents a triumphal and confident, although hardly modest, assertion of Sickert’s artistic and creative powers.

The three Biblical self-portraits also made ambitious claims for the ability of modern art to achieve the monumentality and power of the Old Masters. T.W. Earp, the art critic for the New Statesman, praised The Servant of Abraham for exhibiting ‘the timelessness of all great work, the massive planning and the exuberance of the masters’.22 In the preface to an exhibition of Twentieth-Century Art at the Leicester Galleries in January 1932, Sickert marvelled at the ‘artifice of a colossal head with a miniature execution by Picasso’.23 He argued that ‘We cannot well have pictures on a large scale nowadays, but we can have small fragments of pictures on a colossal scale’, a quotation which the art historian Lilian Browse has employed in connection with The Servant of Abraham.24 The artist’s sister-in-law, Helen Lessore, recorded that Sickert deliberately used a broad technique to demonstrate how he would have treated a grand-scale commission for a mural decoration.25 The contours of the face are built up entirely with amorphous patches of layered colour. Despite his assertion that the production of large-scale pictures was not a feasible objective for contemporary art, Sickert regularly experimented with big canvases in the last few years of his career. The first of these was The Raising of Lazarus (2439 x 915 mm). One newspaper reported that The Servant of Abraham was a study for this ‘forthcoming’ work.26 This theory is unsubstantiated anywhere else, but the scale of the head of the Servant is certainly roughly comparable to that of the bearded head of Christ in The Raising of Lazarus. It is possible that the source photograph for the Servant was a by-product taken during the preparations for the later work.

Ownership

The painting was bought from the artist by his brother-in-law, Major Frederick Lessore, and remained in the possession of the family until 1959 when it was purchased for the Tate Gallery. Frederick Lessore, a portrait sculptor and the brother of Sickert’s third wife, Thérèse, founded the Beaux Arts Gallery in 1923. Alongside R.E.A. Wilson of the Savile Gallery and Oliver Brown of the Leicester Galleries, he acted as one of Sickert’s main dealers during the last years of the artist’s life. With typical financial insouciance, Sickert refused to work on a commission basis but continued to sell his paintings to his dealers for a fixed sum, sometimes in excess of, but more often less, than they were worth. The gallery staged some of the most important solo exhibitions of Sickert during the 1930s.

After Lessore’s death in November 1951 the Beaux Arts Gallery was managed by his wife, Helen, also a painter. Under her direction the gallery became renowned for promoting young British artists working in a realist manner. The Servant of Abraham was hung by her in the gallery as a sort of ‘talisman’ by which she tested the quality of contemporary, rising artists.27 She often hung work by new painters next to it to help her make up her mind.28 When it was not on display, however, the painting resided with the family in the small flat where they lived under the gallery.29 Helen and Frederick’s son, the painter John Lessore, remembers it hanging over one of the beds.

Nicola Moorby

July 2005

Notes

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, p.640.

Reproduced in Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.681 and Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992 (103).

Reproduced at Louvre, Paris, http://cartelen.louvre.fr/cartelen/visite?srv=car_not_frame&idNotice=8844&langue=en , accessed March 2011.

All three reproduced ibid., p.338, figs.229–331 respectively; Baron 2006, nos.706, 708.1, 729, 730 and 737.

Walter Richard Sickert, ‘The Twentieth Century’, in Twentieth Century French Art, exhibition catalogue, Leicester Galleries, London 1932, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford 2000, p.614.

Related biographies

Related essays

- After Camden Town: Sickert’s Legacy since 1930 Martin Hammer

Related catalogue entries

Related archive items

-

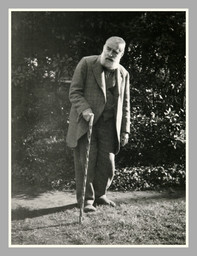

Photograph

-

Portrait of Walter Richard Sickert c.1934–42Photograph

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘The Servant of Abraham 1929 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, July 2005, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www