Turner Bequest CCXXVII a 14, CCLXIII 221, CCLXXX 10, 12, 15–19, 61, 65, 90–91, 93–94, 99–100, 108, 162, 168–192, 194–204, verso of 175, verso of 197

References

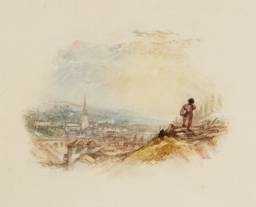

In around 1830 Turner began work on a group of vignette illustrations for a luxury edition of Poems by Samuel Rogers,. Of all the poets whose works Turner illustrated, such as Byron, Scott, Campbell, and Milton, Rogers is probably the least well known today. However, the vignettes that Turner created for Rogers’s Italy (1830) and, shortly thereafter for Poems (1834), are considered to be his finest works of literary illustration.

Samuel Rogers (1763–1855), a wealthy banker turned poet, achieved literary renown with his enormously popular poem The Pleasures of Memory (1792).1 Although he would never surpass this early success, he nonetheless remained deeply engaged in the cultural circles of early nineteenth-century London. His famous breakfast parties at his house in St James Place brought together the artistic and literary luminaries of the day, including Turner and a number of poets whose works Turner would later illustrate. An imaginary version of one such gathering can be seen in Charles Mottram’s engraving of 1823 (Tate T04907). Turner’s first series of literary vignettes for Rogers was the immensely successful illustrations for Italy, published in 1830 (see the Introduction to Rogers’s Italy).

Turner probably began designing vignettes for a second volume of Rogers’s poetry even before Italy was published.2 Poems was published by Thomas Cadell and Edward Moxon in 1834, with the costs again being covered by the poet himself. The volume, which contained thirty-three illustrations by Turner and thirty-four by Stothard, was designed and printed in the same fine style as Italy. The production costs were again enormous, and Rogers later told a friend that he had spent a total of £15,000 publishing the two volumes.3

Poems contains a wide range of Rogers’s writings, beginning with his most acclaimed work, The Pleasures of Memory. Many of the poems in this collection are set in the English countryside, and Turner was again able to draw upon material from his own travels, in this case from his various tours in England and Wales. As with Italy, Turner owned a working copy of Poems, in which he marked potential subjects for illustration (see Tate D36330; Turner Bequest CCCLXVI).4 Although Turner’s painting style is much the same for the two projects, the designs in the later volume tend to be more boldly composed and to be painted in a brighter palette. His mastery of the vignette format is nowhere more visible than in Tornaro and The Alps at Daybreak, which capture enormous disparities of scale and dramatic light effects in their miniature compositions (Tate D27689; D27701; Turner Bequest CCLXXX 172, 184). The ethereal brushwork and shimmering palette of scenes such as Keswick Lake and St Herbert’s Chapel transform well-known English topographical sites into realms of magic and fantasy (Tate D27698, D27697; Turner Bequest CCLXXX 181, 180). A similar sense of enchantment pervades the illustrations to the final poem in Rogers’s collection, The Voyage of Columbus. The poem reflects the popular interest in Columbus’s achievements generated by the publication of Washington Irving’s The Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus in 1828. Rogers’s retelling casts the explorer as a noble and pious hero who brings the light of Christian revelation to the benighted pagan populations of America. Filled with evil spirits, warrior ghosts, and good angels, The Voyage of Columbus inspired some of Turner’s most beautiful and mysterious compositions.

Like its predecessor, Poems met with enormous success. The engravings after Turner’s illustrations were produced by Robert Miller, Robert Wallis, Henry Le Keux and Edward Goodall; their quality was such that Ruskin would describe them as ‘the loveliest engravings ever produced by pure line.’5 The Athenaeum again offered its hearty endorsement of the volume:

We have called this a book: it is something better; it is a gallery of the fairest pictures. The painters were aware of the fastidious taste and nice judgment which would examine and weigh their labours, and they wrought in a manner which transcends all their former exertions. Even ‘Italy’ cannot be compared with ‘The Pleasures of Memory’; ‘Jacqueline,’ and ‘The Voyage of Columbus’. Here we have more variety, and perhaps superior beauty; some of the landscapes of Turner are truly poetic and sublime ... Nor have the engravers been unconscious of the importance of their tasks; Goodall, Finden, and Miller, have surpassed themselves.6

By 1847, a total of 50,000 copies of Poems and Italy had been sold making Turner’s art accessible to an unprecedented number of British viewers.7 Among them was the young John Ruskin, who received a copy of Italy on his thirteenth birthday and would later ‘attribute to the gift the entire direction of my life’s energies.’8 It is Rogers’s biographer, P.W. Clayden, who offers the most eloquent summary of the significance that these vignettes had, both for Turner and for his audience:

There can be little doubt that the illustrations to Italy and the Poems first made Turner known to the vast multitudes of the English people. One of the most vivid recollections of my own boyhood is the wakening up of a new sense of an ideal world of beauty as I lingered over the lovely landscapes on these delightful pages ... there are many whose recollections of these two volumes harmonise with mine, to whom they were an education, and who learned from them to admire Turner before they had actually seen one of his paintings.9

All of Turner’s finished watercolour vignettes related to Rogers’s Poems are in the Turner Bequest. There are also a considerable number of preparatory studies. Catalogue entries are listed below according to their order of appearance in Rogers’s text, with any related preliminary studies. This assigned sequence disrupts the partially consecutive run of Tate accession numbers and Turner Bequest numbers.

| Rogers’s Poems vignette title | Published page reference | Tate number | Turner Bequest (Finberg) number | Rawlinson number and related Tate number | Related studies |

| A Garden | Frontispiece | D27679 | CCLXXX 162 | R373 T04671 | D27534 CCLXXX 17 |

| A Village. Evening | p.7 | D27685 | CCLXXX 168 | R374 T05114 | |

| The Gipsy | p.11 | D27690 | CCLXXX 173 | R375 | |

| Leaving Home | p.15 | D27686 | CCLXXX 169 | R376 T04672 | |

| Greenwich Hospital | p.33 | D27693 | CCLXXX 176 | R377 T04673 | D27611 CCLXXX 94 |

| Keswick Lake | p.36 | D27698 | CCLXXX 181 | R378 | D27608 CCLXXX 91 |

| St. Herbert’s Chapel | p.40 | D27697 | CCLXXX 180 | R379 T04674 and T06162 | |

| An Old Manor-House | p.63 | D27718 | CCLXXX 201 | R380 T05115 and T06163 | D27532 CCLXXX 15 |

| Tornaro | p.80 | D27689 | CCLXXX 172 | R381 T06164 and T06644 | |

| A Village-Fair | p.84 | D27717 | CCLXXX 200 | R382 T04675 and T06165 | |

| Traitor’s Gate, Tower of London | p.88 | D27694 | CCLXXX 177 | R383 T05116 and T06166 | D27610 CCLXXX 93 |

| St. Anne’s Hill, I | p.91 | D27687 | CCLXXX 170 | R384 T06167 | |

| A Hurricane in the Desert (The Simoom) | p.94 | D27712 | CCLXXX 195 | R385 | D27578 CCLXXX 61 D27582 CCLXXX 65 |

| Venice (The Rialto – Moonlight) | p.95 | D27713 | CCLXXX 196 | R386 T06645 | D27625 CCLXXX 108 |

| Valombrè | p.144 | D27702 | CCLXXX 185 | R387 | |

| St Pierre’s Cottage | p.146 | D27700 | CCLXXX 183 | R388 | |

| St Julienne’s Chapel | p.151 | D27703 | CCLXXX 186 | R389 T04676 | |

| Captivity | p.172 | D27704 | CCLXXX 187 | R390 | D20817 CCXXVII a 14 D25343 CCLXIII 221 D27527 CCLXXX 10 |

| An Old Oak | p.176 | D27691 | CCLXXX 174 | R391 T05117 | D27533 CCLXXX 16 |

| Ship-building (An Old Oak Dead) | p.178 | D27692 | CCLXXX 175 | R392 T05118, T05119, and T05797 | D41513 Verso of CCLXXX 175 |

| The Boy of Egremond | p.184 | D27695 | CCLXXX 178 | R393 T05120 | |

| Bolton Abbey | p.186 | D27696 | CCLXXX 179 | R394 T05121 | |

| The Alps (The Alps at Daybreak) | p.191 | D27701 | CCLXXX 184 | R395 T05122 | |

| Loch Lomond | p.203 | D27699 | CCLXXX 182 | R396 T06168 and T06646 | |

| St Anne’s Hill, II (In the Garden) | p.214 | D27688 | CCLXXX 171 | R397 T05123 and T06169 | |

| Columbus and his Son | p.219 | D27705 | CCLXXX 188 | R398 T05124 and T06170 | |

| Columbus Setting Sail | p.227 | D27706 | CCLXXX 189 | R399 T05125 and T06171 | D27535 CCLXXX 18 D27536 CCLXXX 19 |

| The Vision of Columbus | p.233 | D27714 | CCLXXX 197 | R400 T05126 and T06172 | D40175 Verso of CCLXXX 197 D27720 CCLXXX 203 D27721 CCLXXX 204 |

| Land Discovered by Columbus | p.248 | D27707 | CCLXXX 190 | R401 T05127 and T06173 | |

| The Landing of Columbus | p.251 | D27708 | CCLXXX 191 | R402 T05128, T05129, and T06174 | D27711 CCLXXX 194 D27529 CCLXXX 12 D27616 CCLXXX 99 |

| A Tempest – Voyage of Columbus | p.264 | D27719 | CCLXXX 202 | R403 T04677 and T05130 | D27617 CCLXXX 100 |

| Cortes and Pizarro | p.265 | D27709 | CCLXXX 192 | R404 T05131 | |

| Evening (Datur Hora Quieti) | p.296 | D27716 | CCLXXX 199 | R405 T05132 and T05133 | D27607 CCLXXX 90 |

| Going to School | Unpublished | D27715 | CCLXXX 198 |

The titles given follow those listed by Jan Piggott in his catalogue of Turner’s vignettes, which in turn are those given by Samuel Rogers or the publisher Edward Moxon on the finished portfolio engravings and in the 1838 quarto editions.10

How to cite

Meredith Gamer, ‘Watercolours Related to Samuel Rogers’s Poems c.1830–2’, subset, August 2006, revised by Matthew Imms, September 2016, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www