Joseph Mallord William Turner Temples of Paestum, for Rogers's 'Italy' c.1826-7

Joseph Mallord William Turner,

Temples of Paestum, for Rogers's 'Italy'

c.1826-7

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Temples of Paestum, for Rogers’s ‘Italy’ circa 1826–7

D27665

Turner Bequest CCLXXX 148

Turner Bequest CCLXXX 148

Watercolour, gouache, and pen and ink, approximately 95 x 180 mm on white wove paper, 240 x 305 mm

Stamped in black ‘CCLXXX 148’ bottom right

Stamped in black ‘CCLXXX 148’ bottom right

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Exhibition history

1904

National Gallery, London, various dates to at least 1904 (206).

1934

[Loan Series A], Art Gallery and Museum, Burton-on-Trent, September–December 1934 and Public Museum, Luton, January–February 1935, Manx Museum, Douglas, Isle of Man, August–November 1936, Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne, January–March 1937, Historic Rooms, Todmorden, January–March 1938 (no catalogue but numbered 17).

1935

Drawings and Sketches by J.M.W. Turner, National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, December 1935–April 1936 (51a).

1946

Loan of Turner Watercolours from the Turner Bequest, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, September 1946–February 1947 (no catalogue but numbered 17).

1953

J.M.W. Turner R.A. 1775–1851: Pictures from Public and Private Collections in Great Britain, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, February–March 1953 (174).

1959

Loan of Turner Watercolours from the British Museum, Cannon Hall, Cawthorne, December 1959–April 1960 (no catalogue but numbered 17).

1960

Loan Exhibition of Turner Watercolours from the British Museum, Wakefield Art Gallery, February–April 1960 (no catalogue but numbered 17).

1974

Turner 1775–1851, Royal Academy, London, November 1974–March 1975 (274).

1976

J.M.W. Turner, Akvareller og tegninger fra British Museum, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, February–May 1976 (36).

1976

William Turner und die Landschaft seiner Zeit, Hamburger Kunsthalle, May–July 1976 (53, reproduced).

1989

Colour into Line: Turner and the Art of Engraving, Tate Gallery, London, October 1989–January 1990 (63, reproduced).

1993

Turner’s Vignettes, Tate Gallery, London 1993 (7, reproduced).

1995

Sketching the Sky: Watercolours from the Turner Bequest, Tate Gallery, London, September 1995–February 1996 (no number).

2008

Turner e l’Italia/Turner and Italy, Palazzo dei Diamanti, Ferrara, November 2008–February 2009, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh, March–June 2009, Szépmûvészeti Múzeum, Budapest, July–October 2009 (58, reproduced in colour).

References

1903

E.T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn (eds.), Library Edition: The Works of John Ruskin: Volume I: Early Prose Writings 1834–1843, London 1903, pp.233, 244.

1904

E.T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn (eds.), Library Edition: The Works of John Ruskin: Volume XIII: Turner: The Harbours of England; Catalogues and Notes, London 1904, pp.380–1.

1906

E.T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn (eds.), Library Edition: The Works of John Ruskin: Volume XXI: The Ruskin Art Collection at Oxford, London 1906, p.214.

1909

A.J. Finberg, A Complete Inventory of the Drawings in the Turner Bequest, London 1909, vol.II, p.900, as ‘Paestum’.

1966

Adele Holcomb, ‘J.M.W. Turner’s Illustrations to the Poets’, unpublished Ph.D thesis, University of California, Los Angeles 1966, pp.37, 49.

1974

Martin Butlin, Andrew Wilton and John Gage, Turner 1775–1851, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1974, no.274.

1976

David Loshak and Andrew Wilton, J.M.W. Turner, Akvareller og tegninger fra British Museum, exhibition catalogue, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen 1976, no.36.

1976

Werner Hofmann, Andrew Wilton, Siegmar Hosten and others, William Turner und die Landschaft seiner Zeit, exhibition catalogue, Hamburger Kunsthalle 1976, no.53 reproduced.

1979

Andrew Wilton, The Life and Work of J.M.W. Turner, Fribourg 1979, p.439 no.1173, reproduced.

1983

Cecilia Powell, ‘Turner’s vignettes and the making of Rogers’s “Italy” ’, Turner Studies, vol.3, no.1, Summer 1983, pp.4, 8, 10, reproduced fig.9.

1984

Cecilia Powell, ‘Turner on Classic Ground: His Visits to Central and Southern Italy and Related Paintings and Drawings’, unpublished Ph.D thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London 1984, pp.191 note 93, 280 note 47, 287 note 73, 290 note 90, 535 note 26, reproduced pl.182.

1987

Cecilia Powell, Turner in the South: Rome, Naples, Florence, New Haven and London 1987, pp.83–5, reproduced fig.85.

1989

Anne Lyles and Diane Perkins, Colour into Line: Turner and the Art of Engraving, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1989, no.63, p.67 reproduced, as ‘Paestum’.

1990

Luke Herrmann, Turner Prints: The Engraved Work of J.M.W. Turner, Oxford 1990, p.187, reproduced fig.150.

1993

Jan Piggott, Turner’s Vignettes, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1993, no.7, pp.38–9, 82 reproduced, 97.

1995

Sketching the Sky: Watercolours from the Turner Bequest, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1995, p.5.

2008

James Hamilton, Nicola Moorby, Christopher Baker and others, Turner e l’Italia, exhibition catalogue, Palazzo dei Diamanti, Ferrara 2008, no.58, pp.57, [195], 202, reproduced in colour, as ‘I templi di Paestum’.

2009

James Hamilton, Nicola Moorby, Christopher Baker and others, Turner & Italy, exhibition catalogue, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh 2009, p.60, reproduced in colour, p.[61], pl.64.

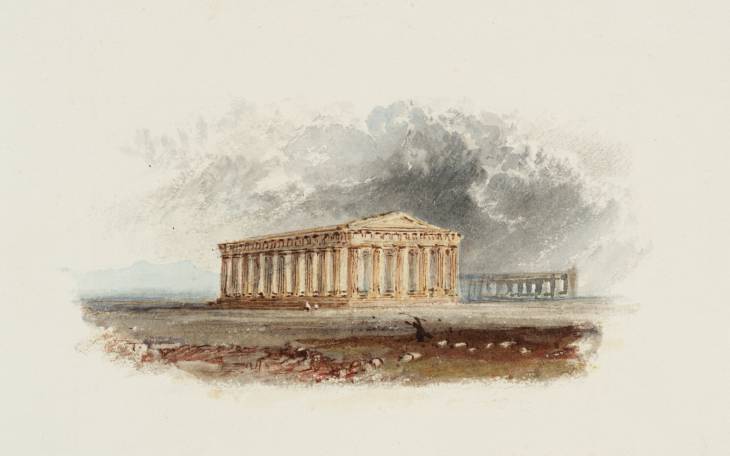

This vignette was engraved by John Pye and appears as the head-piece for the forty-third section of Rogers’s Italy, entitled ‘Pæstum’.1 Pye was paid £35 for each of his engravings of Paestum and Tivoli (see Tate D27683; Turner Bequest CCLXXX 166) and the high price reflects his rank as one of the most important engravers of his day.2 Most of the other engravers of Italy vignettes were only paid 20 guineas.

The three fifth-century Doric Greek temples at Paestum were rediscovered in the mid eighteenth century and soon became the southernmost destination for many English travellers on the Grand Tour, including Turner himself during his 1819–20 journey through Italy.3 Turner here depicts two buildings; in the centre the so-called Temple of Neptune and in the distance on the right-hand side, a basilica (now both identified as part of a Sanctuary of Hera). A preparatory study for this subject shows that the artist considered presenting a distant view of all three temples (see Tate, D72609; Turner Bequest CCLXXX 92). However, in the end he decided to provide a close-up, three-quarter view of the central, and best preserved temple.

Turner had produced numerous sketches of the temples of Paestum during his 1819 tour of Italy (see Tate, D15945–6, D15967–73, D15980, D15995–7; Turner Bequest CLXXXVI 19a–19b, 28a–31a, 35, 42a–43a). However, although Turner may have referred to these drawings to refresh his memory, he certainly did not copy from them directly. Cecilia Powell has pointed out that Turner inaccurately represents the central temple with only eleven lateral columns, even though he noted the correct number in his earlier on-site sketches (see Tate D13953, Turner Bequest CLXXII 20 and D15971, D15972; Turner Bequest CLXXXVI 29–29b).4 She also observes that Turner has depicted the temple in a restored, complete state, rather than as the group of ruins which he actually saw and sketched.5 Nor was Turner overly concerned with correctly illustrating Rogers’s text down to every last detail. As Cecilia Powell has noted, Rogers’s describes a buffalo driver, who, in passing by the temples, ‘points to the work of magic and moves on,’ but Turner’s image shows a shepherd, who appears to be guiding his flock away from the impending storm.6

Rogers’s visit to Paestum made a deep impression upon him and his description of this experience was to become one of the most popular chapters in Italy.7 His lines would have already been familiar to many readers, for they had appeared along with his poem A Human Life (1819) and again in a new edition of his Poems in 1822. The verses offer a characteristic expression of Rogers’s response to the ancient architecture and history of Italy. For the poet, the ruins of Italy are at one with their natural surroundings but nonetheless subject to the ruinous effects of time:

They stand between the mountains and the sea;

Awful memorials, but of whom we know not!

...

Nothing stirs

Save the shrill-voiced cicala flitting round

On the rough pediment to sit and sing;

Or the green lizard rustling through the grass,

And up the fluted shaft with short quick spring,

To vanish in the chinks that Time has made.

(Italy, pp.207–9)

Awful memorials, but of whom we know not!

...

Nothing stirs

Save the shrill-voiced cicala flitting round

On the rough pediment to sit and sing;

Or the green lizard rustling through the grass,

And up the fluted shaft with short quick spring,

To vanish in the chinks that Time has made.

(Italy, pp.207–9)

Although Rogers’s text describes calm weather and the air ‘sweet with violets’, Turner presents the temples amidst gathering storm clouds. The reason for this can be found in the final and crucial lines of the passage on Paestum. Referring again to the temples, Rogers writes:

But what are These still standing in the midst?

The Earth has rocked beneath; the Thunder-stone

Passed thro’ and thro’, and left its traces there;

Yet still they stand as by some Unknown Charter!

Oh, they are Nature’s own! and, as allied

To the vast Mountains and the eternal Sea,

They want no written history; theirs a voice

For ever speaking to the heart of Man!

(Italy, p.211)

The Earth has rocked beneath; the Thunder-stone

Passed thro’ and thro’, and left its traces there;

Yet still they stand as by some Unknown Charter!

Oh, they are Nature’s own! and, as allied

To the vast Mountains and the eternal Sea,

They want no written history; theirs a voice

For ever speaking to the heart of Man!

(Italy, p.211)

Turner here represents the temples withstanding the blows of the ‘Thunder-stones’ (an archaic term for thunderbolt) to which Rogers refers. Able to hold their own against the forces of nature, these man-made monuments have become ‘Nature’s own’, and thus a permanent part of the natural landscape. Although the storm and lightning are considerably more subdued in Turner’s watercolour than in Pye’s engraving, Turner frequently neglected to paint the skies in his Italy vignettes and seems instead to have provided specific instructions to the engravers about how to depict them. He carefully oversaw the engraving of his designs and it is likely that he intended these effects to be rendered with greater intensity in the final illustration. Even so, Ruskin would later chide Pye for having rendered the storm too feebly.8

Turner combined ancient structures and sublime landscape effects in a number of his other works. This vignette is closely linked to a colour study (see Tate, D36070; Turner Bequest CCCLXIV 224) and related mezzotint from the ‘Little Liber’ series, also entitled ‘Paestum’, which shows one of the ancient temples with lightning and an animal skeleton in the foreground. The ‘Little Liber’ designs date to 1824–26, around the same time that Turner produced his illustrations for Italy, and this image may well have been inspired by Rogers’s lines.9 Turner again combines these motifs in later works, including Stone Henge, circa 1827 (Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum),10 engraved in 1829 for Picturesque Views in England and Wales,11 and Temple of Poseidon at Sunium (Cape Colonna), circa 1834 (Tate, T07561).12

Cecilia Powell has noted that the faint pencil lines drawn around this vignette were made by the engravers during the process of squaring-up the designs for reduction.13

Verso:

Inscribed by unknown hands in pencil ‘4 | a’ centre right and ‘CCLXXX 148’ bottom centre

Stamped in black ‘CCLXXX 148’ centre

Stamped in black ‘CCLXXX 148’ centre

Meredith Gamer

August 2006

How to cite

Meredith Gamer, ‘Temples of Paestum, for Rogers’s ‘Italy’ c.1826–7 by Joseph Mallord William Turner’, catalogue entry, August 2006, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www