Sublime History: Louis Chéron’s Vulcan Catching Mars and Venus in his Net, Henry Gibbs’s Aeneas and his Family Fleeing Burning Troy and Godfrey Kneller’s Elijah and the Angel

Lydia Hamlett

History painting as a genre – including historical, classical and biblical scenes – came to be associated with the notion of the sublime as a response to the rediscovery in the late sixteenth century of the ancient treatise Peri Hypsous by the author known as the Pseudo-Longinus, which dealt with the subject.1 It continued to be closely tied to sublime discourse through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. At the beginning of the seventeenth century the painter and theorist Jonathan Richardson called history painting and portraiture the only genres capable of having a sublime effect.2 The painter Sir Joshua Reynolds in his Discourses on Art at the very end of the eighteenth century associated history painting with the ‘grand style’ and once again linked it explicitly with the sublime.3

In the seventeenth century, the category of history painting included depictions of episodes from ancient and biblical history, and also allegorical scenes that reflected the lives of patrons: celebrating their contributions, and those of their political allies, to more recent histories. This included what we now call ‘decorative history paintings’, which worked as an ensemble with architecture. For example, Richardson thought it quite appropriate to describe James Thornhill – who decorated the walls and ceilings of many a country house as well as the ceiling of the Painted Hall at Greenwich Hospital – as ‘an Excellent History-Painter’. History painters such as Thornhill, Antonio Verrio and Louis Laguerre before him were accordingly paid sizeable sums because of the prestige attached to the genre.

Boughton House in Northamptonshire is dubbed the ‘English Versailles’, after the palace of Louis XIV of France, because of its architectural style and opulent interior, which includes a series of rooms painted with mythological scenes. These were executed by the French Protestant painter Louis Chéron, who had previously lived in Paris and studied at the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. Although it was common for scenes to be chosen from classical literature and specifically from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, in the rooms at Boughton the spectator has an especially intimate relationship with them, as the fictive space is integral to the real domestic sphere. We confront the same gods again and again in each room, and the stories are frequently suited to the function of the room they decorate. The visitor dined and slept alongside the gods, who are shown as human-sized figures. While breathtaking views into the heavens were often intended to have a sublime effect and inspire the viewer below with great ideas, at Boughton the effect is often its opposite – bathos – especially when drunken or lecherous gods are displayed which remind us of the more mundane and undignified aspects of human behaviour.

Louis Chéron 1660–1725

Vulcan Catching Mars and Venus in his Net circa 1695

Oil on paper laid on canvas

support: 495 x 391 mm; frame: 677 x 585 x 110 mm

Tate T00578

Purchased 1963

Fig.1

Louis Chéron

Vulcan Catching Mars and Venus in his Net circa 1695

Tate T00578

Louis Chéron 1660–1725

Boughton House Main Hall Ceiling c. 1705–7

Oil on plaster

7.53 x 15.44 m

Collection of The Trustees of the 9th Duke of Buccleuch's Chattels Fund

© Photo Lydia Hamlett

Fig.2

Louis Chéron

Boughton House Main Hall Ceiling c. 1705–7

Collection of The Trustees of the 9th Duke of Buccleuch's Chattels Fund

© Photo Lydia Hamlett

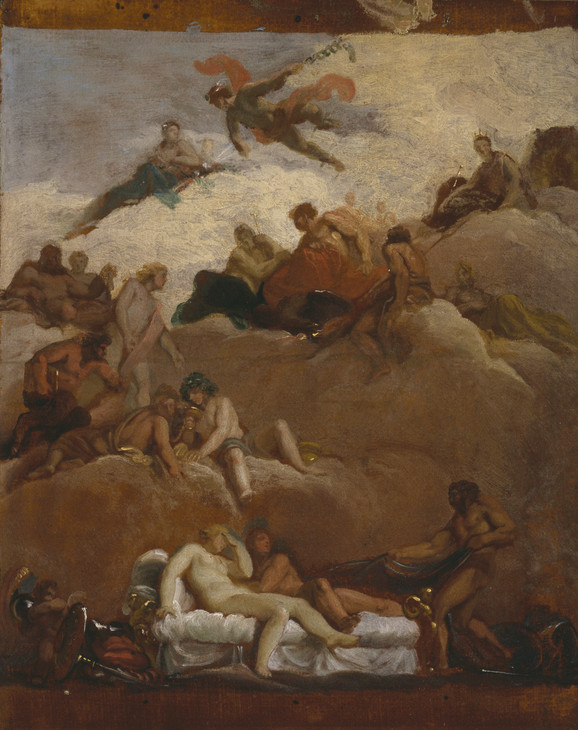

The sketch by Chéron in Tate’s collection (T00578, fig.1) for the ceiling of the third State Room – the bedchamber to be used by the visiting monarch – shows a story told by Homer and Ovid of Vulcan retracting an invisible net which he had used to catch his wife Venus in an adulterous liaison with Mars. Above the bed scene is an assembly of the gods including Apollo, or the sun god Helios, who revealed the betrayal and who gestures down towards it. The sketch, which must have been done before 1695, and the ceiling as it is today are very similar (fig.2). The only major change is that on the ceiling Venus looks down instead of up. She looks over her right shoulder, shielding her flushed face with her hand in embarrassment. The net depicted in the ceiling is also less substantial than in the sketch, in accordance with the narrative.

The term decorative was retrospectively applied to history paintings that were located within an architectural framework. Increasingly, from the so-called ‘taste debates’ of the early eighteenth century, decorative was used pejoratively to emphasise such works’ adorning function and to deny them any depth of meaning, function or effect. After the publication of The Tablature of Hercules (1713) by Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury, the term history painting was generally applied only to large-scale easel paintings. Shaftesbury dismissed wall and ceiling paintings as ‘those wilder sorts of painting’ as his aim was to define a new kind of history painting, one that had a clear intelligible message transmitted with visual simplicity. He linked history painting inextricably with ‘tablature’, which comes from the Latin word ‘tabula’, implying the dimensions of a cloth or board. According to Shaftesbury, as the idea expressed in history painting was a singular whole, by its very nature it needed to be expressed on a single plane. Sprawling painted interiors with various interlocking planes, experienced from limitless different angles, were no longer suitable.

Henry Gibbs 1631–1713

Aeneas and his Family Fleeing Burning Troy 1654

Oil on canvas

support: 1550 x 1598 mm;

Tate T06782

Purchased 1994

Fig.3

Henry Gibbs

Aeneas and his Family Fleeing Burning Troy 1654

Tate T06782

Sir Godfrey Kneller 1646–1723

Elijah and the Angel 1672

Oil on canvas

support: 1765 x 1486 mm;

Tate N06222

Purchased 1954

Fig.4

Sir Godfrey Kneller

Elijah and the Angel 1672

Tate N06222

Decorative history paintings were no longer seen to guarantee success in conveying a clear and simple message to the spectator, as multiple lines of sight offered different ways to experience these paintings For Shaftesbury, the key to history painting was to present a plausible account of a historical event, and to eliminate confusion in both subject matter and composition.4 This entailed the presentation of an obvious moment in time, in which the main character was clearly identified, and where the utmost care was taken not to detract from authenticity, for example through anachronistic detail or uneasy perspective. Human activity – rather than landscape or animals – was supposed to be the sole focus.5 These ideas were very different from the decorative schemes that he was railing against, such as at Boughton House where the ceilings include an overwhelming mêlée of figures who all jostle for position. Of course, examples of such paintings did exist in England before Shaftesbury wrote his treatise, and not just by Old Masters. In Tate’s collection there is a large painting showing Aeneas Fleeing Troy by the English painter Henry Gibbs (T06782, fig.3) and a painting by the Dutch artist Godfrey Kneller, Elijah and the Angel (N06222, fig.4), which the artist brought over to England to display in Whitton House. Both are easel paintings that focus on a single classical or biblical event, and which are composed on a single plane, presenting one great episode in the most effective way.

Notes

For more on Pseudo-Longinus’s Peri Hypsous, see Lydia Hamlett, Longinus and the Baroque Sublime in Britain in Nigel Llewellyn and Christine Riding (eds.), The Art of the Sublime, January 2013.

Jonathan Richardson, Two Discourses. I. An Essay on the Whole Art of Criticism as it Relates to Painting. II. An Argument in Behalf of the Science of a Connoisseur; Wherein Is Shewn the Dignity, Certainty, Pleasure, and Advantage of It, London 1719, p.75; Jonathan Richardson, An Essay on the Theory of Painting, London 1725, p.249; Carol Gibson-Wood, Jonathan Richardson: Art Theorist of the English Enlightenment, New Haven and London 2000, p.178.

Edmond Malone (ed.), The Works of Sir Joshua Reynolds, London 1797, Discourse XV. The second volume of the third edition from 1801 is available at http://www.archive.org/stream/worksofsirjoshua02reyniala#page/178/mode/2up , accessed 9 June 2011.

Lydia Hamlett was Research Assistant (The Sublime Object: Nature, Art and Language), Tate.

How to cite

Lydia Hamlett, ‘Sublime History: Louis Chéron’s Vulcan Catching Mars and Venus in his Net, Henry Gibbs’s Aeneas and his Family Fleeing Burning Troy and Godfrey Kneller’s Elijah and the Angel’, in Nigel Llewellyn and Christine Riding (eds.), The Art of the Sublime, Tate Research Publication, January 2013, https://www