Tour of Scotland, 1818 for Scott’s Provincial Antiquities; sketchbooks 1818–20

From the entry

Turner’s visit to Scotland in 1818 was made at the prompting of Walter Scott and his publisher Robert Cadell, who had proposed to publish a topographical part-work publication of views with accompanying descriptions of the Provincial Antiquities and Picturesque Scenery of Scotland. The project began an association with the author that lasted until his death in 1832, and with his publisher for several more years. Turner’s subsequent tours of Scotland in 1822, 1831 and 1834 all had a Scott connection. The Provincial Antiquities was conceived as a twelve-part publication, with a two-volume bound edition to follow. It was dedicated to subjects of historical and picturesque interest around East Lothian and Midlothian, with the prospect of further series covering other parts of the country to follow; although, in the event, the series was cut short after ten numbers. Turner contributed ten watercolours to be engraved which he based on sketches made in three sketchbooks used on his tour of Scotland in the ...

References

Turner’s visit to Scotland in 1818 was made at the prompting of Walter Scott and his publisher Robert Cadell, who had proposed to publish a topographical part-work publication of views with accompanying descriptions of the Provincial Antiquities and Picturesque Scenery of Scotland.1 The project began an association with the author that lasted until his death in 1832, and with his publisher for several more years. Turner’s subsequent tours of Scotland in 1822, 1831 and 1834 all had a Scott connection.

The Provincial Antiquities was conceived as a twelve-part publication, with a two-volume bound edition to follow. It was dedicated to subjects of historical and picturesque interest around East Lothian and Midlothian, with the prospect of further series covering other parts of the country to follow; although, in the event, the series was cut short after ten numbers.

Turner contributed ten watercolours to be engraved which he based on sketches made in three sketchbooks used on his tour of Scotland in the autumn of 1818. He also made two title-page vignettes for the 1826 bound edition. With just a few weeks to collect all his material, the artist’s movements, and those of his pencil, were determined almost exclusively by the proposed content of the publication.

Turner set off on his trip towards the end of October;2 a journey from London of about 60 hours by coach.3 As notes in the Edinburgh, 1818 and Scotch Antiquities sketchbooks show, he passed through ‘Grantham’, ‘Newark’, ‘York’, ‘Newcastle’, ‘Morpeth’, and ‘Dunbar’ (Tate D40916, D13586; Turner Bequest CLXVII Inside back cover, CLXVI 70a). No sketches were executed until he reached Newcastle, where he made a light, but very careful drawing of the city from a bridge over the Tyne (Tate D13588; Turner Bequest CLXVII 2), which became the basis of a Rivers of England watercolour design: Newcastle-on-Tyne, circa 1823 (Tate D18144; Turner Bequest CCVIII K).4 From there he travelled east along the Tyne to North Shields were he made a number of sketches in the Edinburgh, 1818 sketchbook, perhaps also connected to that project (see Tate D13473; Turner Bequest CLXVI 13).

As he approached the border, Turner made a single quick sketch of Berwick-upon-Tweed (Tate D13490–D13491; Turner Bequest CLXVI 21a–22). From here he began a route up the east coast of Scotland, making a detour from the old Great North Road to follow the coast between St Abbs (Tate D13324; Turner Bequest CLXV 2) and Cockburnspath, where he drew the Pease Bridge (Tate D13378 and D13379; Turner Bequest CLXV 32a and 33). On the way he drew his first Provincial Antiquities subject, Fast Castle (Tate D13444; Turner Bequest CLXV 66a), although, as he probably anticipated, he was not commissioned to illustrate it.

Sketching began in earnest around North Berwick and Dunbar. Following the sequence of sketches, Katrina Thomson suggests that Turner arrived by coach in North Berwick, and then walked back south along the coast to Dunbar, a distance of about twelve miles, before returning to North Berwick by coach. His object was to collect sketches for three of his commissioned subjects, Dunbar Castle, Tantallon Castle and the Bass Rock, and there are dozens of sketches of all three. Sketches of the Bass Rock informed his final design, although the watercolour was more closely based on a sketch made in 1822 (see below). There are also sketches that record the rest of the craggy coastline between Dunbar and North Berwick.

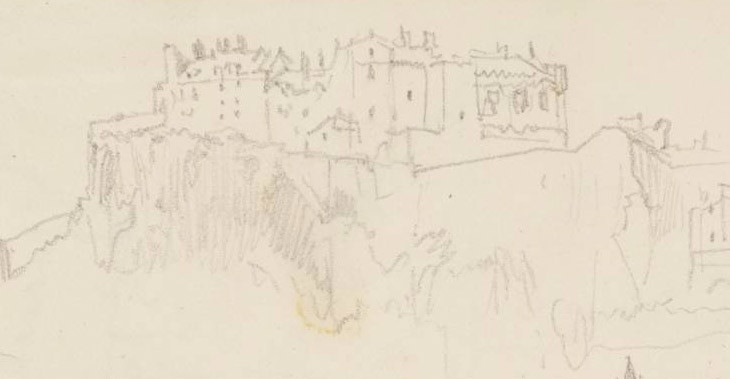

From North Berwick Turner coached to Edinburgh, which he made his base for the rest of the tour, sketching in the city and visiting sites within a fifteen-mile radius. Here he made sketches that became the basis for Edinburgh from Calton Hill, circa 1819, Edinburgh High Street, circa 1818, and Heriot’s Hospital, circa 1819, as well as taking views of and in the city. Most notable is a sequence of views of Edinburgh from near the Water of Leith which Turner may have made in preparation for Provincial Antiquities view that he never executed,5 as well as a sustained interest in Edinburgh Castle and Calton Hill.

Turner’s exact movements for the two weeks he spent in and around Edinburgh are not recorded, and the rather jumbled arrangement of sketches does not provide much information about the order in which subjects were visited. A number of possible day trips, however, can be suggested.

A trip from Edinburgh to Dalkeith, Crichton and Borthwick to take sketches for Borthwick Castle, 1818, and Crichton Castle, circa 1818, forms a logical route, though Katrina Thomson suggests that Roslin Castle was probably reserved for a separate excursion.6

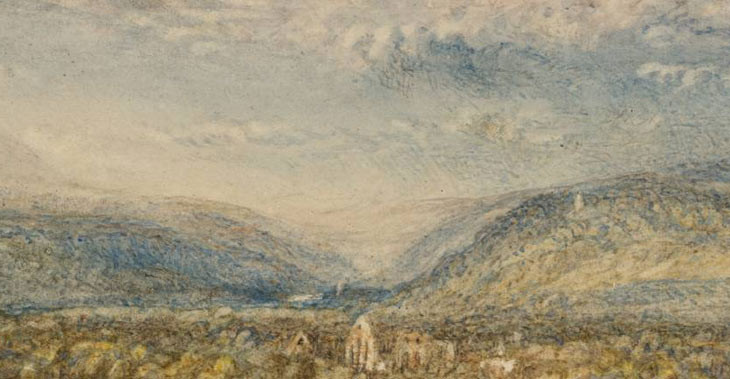

Linlithgow Palace was a subject that seems to have offered Turner endless variety and possibility, as he made dozens of sketches of it and the adjacent St Michael’s Church while circling Linlithgow and the Loch. He must have spent several hours there, and Eric Shanes has suggested that some of the sketches were made as daylight was fading,7 as in the finished watercolour, Linlithgow Palace, 1821 (see below). Katrina Thomson suggests that Turner’s day trip to Linlithgow, presumably made in a hired gig, took in Blackness Castle, and it was on his return to Edinburgh that he made a series of sketches of ‘the distant panorama of the city, as he approached from its northern outskirts (see Tate D13685; Turner Bequest CLXVII 59 verso).8 However, if a sketch of the view along the Firth of Forth, inscribed, ‘The Effect of Twylight near Edinburgh’ (Tate D13562–D13563; Turner Bequest CLXVI 58a–59), was really made in the final moments of the day, then it seems unlikely that he would have had time to make so many detailed drawings of the city while there was still light to see by, suggesting either that the Linlithgow studies were made earlier in the day, or that the other sketches may have been made on a separate excursion, perhaps taking in Blackness, Hopetoun House, and several views along the Firth of Forth.

One day trip that was recorded – although not the date – was to Craigmillar Castle with fellow Provincial Antiquities artists Hugh William Williams and the Revd John Thomson of Duddingston. Turner either knew that Thomson would be illustrating Craigmillar, or was restricted by his colleagues’ company and schedules, as he made only three sketches of the building (see Tate D13743; Turner Bequest CLXVII 85a), far fewer than he habitually made of subjects that he was to illustrate.9 As it happens, however, one of these sketches (Tate D13707; Turner Bequest CLXVII 67a) provided the basis for a later illustration to Scott’s Prose Works, chosen in preference to any of those he made in 1834: Craigmillar Castle, circa 1833 (whereabouts unknown).10 He remained secretive about his sketches, refusing to show them to his fellow artists, and giving chase when Mrs Thomson playfully ‘seized the [sketch]book’ that Turner had left on the hall table in Thomson’s home, The Manse, ‘and ran off with it’.11

This is the only known excursion that Turner made with fellow artists, although he spent time with various artists in Edinburgh, including John Christian Schetky, and may have met the Provincial Antiquities engraver, William Home Lizars, who was present in the city at the time of his visit. Crichton and Roslin were both also illustrated by Thomson, and Borthwick by Williams, so Turner may have had their company when he visited these sites. Furthermore, several sketches of Linlithgow (see Tate D13671; Turner Bequest CLXVII 49) shows two figures inspecting the palace, church and grounds, and may represent members of Turner’s party, or just tourists whom he did not know. There are reports, however, of him shunning company: missing a dinner party given in his honour by the portrait painter William Nicolson, and behaving like ‘such a stick’ that Jane and John Christian Schetky concluded that they ‘did not think the pleasure of showing him to [their] friends would be adequate to the trouble and expense’.12

Turner sketched several Provincial Antiquities subjects that he was not commissioned to paint such as Fast Castle and Craigmillar. He also made sketches of Dalkeith, Hawthornden Castle, Leith, Holyrood House, and various views of Edinburgh, as well as sketching subjects that were at one time proposed, but in the event not included in the publication: South Queensferry, Hopetoun House, and Blackness Castle.13

Other, non-Provincial Antiquities, subjects were all visited on the way to or from commissioned sites. These include views along the Firth of Forth from Blackness in the west to Portobello in the east, including Port Edgar, South Queensferry, Crammond, Lauriston Castle and Leith. On a brief trip across to the Fife shore of the Forth he drew Rosyth Castle and North Queensferry.

Turner returned home by a similar route, stopping off at Farnley Hall in North Yorkshire on the way to visit his friend and patron Sir Walter Fawkes. He was back in London by 1 December when he attended the General Meeting at the Royal Academy.14

Turner took three sketchbooks with him to Scotland in 1818; these were: Bass Rock and Edinburgh (Tate D13322–D13448; D40682–D40684 complete sketchbook; Turner Bequest CLXV); Edinburgh, 1818 (Tate D13449–D13586; D40934–D40937; Turner Bequest CLXVI complete group); and Scotch Antiquities (Tate D13587–D13654; D13656–D13747; D40913–D40916; Turner Bequest CLXVII complete group). All three were used concurrently, although Bass Rock and Edinburgh, the smallest of the three, tended to be used for the most rapid visual notes, especially on the coast, while Scotch Antiquities, the largest book, contains the most developed drawings, many of which became the basis for illustration designs. Edinburgh, 1818, the widest sketchbook proved particularly useful for panoramic double-page sketches. A further sketchbook – Scotland and London (Tate D13814– D13858; D40885–D40886; complete sketchbook; Turner Bequest CLXX) – is associated with the tour because is contains three studies for Provincial Antiquities illustrations, based on sketches collected during the tour.

Turner’s watercolour designs, based on his Scottish sketches, were delivered to a number of engravers in time to be published in issues of the Provincial Antiquities between 1818 and 1826. He used a standard format of about 165 x 241 mm a note of which he made in the back of the Scotch Antiquities sketchbook (‘6½ by 9½’ [inches]) (Tate D40916; Turner Bequest CLXVII Inside Back Cover) and on an unfinished watercolour sketch (Tate D25325; Turner Bequest CCLXIII 203). The format corresponds to the average dimensions of the subsequent engravings after the watercolours.

Turner maintained his artistic involvement even after submitting the watercolours for engraving by correcting proofs with notes and additions in pencil or scratching out. Two known ‘touched’ proofs are extant: one of Edinburgh from Calton Hill (George Cook after J.M.W. Turner, circa 1820, engraving with additions in pencil by Turner, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), which has annotations and sketches by Turner in the margins,15 and one of Bass Rock with notes to the engraver, Miller, to darken the sky, and scraping out to extend the length of the lightning bolt (William Millar after J.M.W. Turner, circa 1826, engraving with additions in pencil and scratching out by Turner, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston).16

A full list of the illustrations for the ten numbers (issues) of the Provincial Antiquities, and the 1826 two-volume edition, are provided by Katrina Thomson with their artist and engraver, date of publication, accompanying essay and description by Walter Scott and placement within the two-volume edition.17 Below is a list of the watercolour designs that Turner contributed, with reference to the sketches that they were based upon. They are listed in the order of the issue or volume number in which the engraved versions were first published.

IV (November 1820): Edinburgh from Calton Hill, circa 1819 (watercolour, National Gallery of Scotland);21 see Tate D13651–D13652–D13654; Turner Bequest CLXVII 39a–40–41

VI (June 1822): Tantallon Castle, 1821 (Manchester City Art Galleries);22 see Tate D13598–D13599; Turner Bequest CLXVII 8a–8b

VI: Linlithgow Palace, 1821 (Manchester City Galleries);23 see Tate D13678–D13679, D13680; Turner Bequest CLXVII 52a–53, 53a; and Linlithgow Palace a sheet from the ‘Smaller Fonthill sketchbook’, 1801, (Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts)

VII (November 1822): Heriot’s Hospital, circa 1819 (watercolour, National Gallery of Scotland);24 see Tate D13744–D13745; Turner Bequest CLXVII 86–86a

IX (December 1824): Dunbar, circa 1823 (private collection);26 see Tate D13496–D13597, D13633–D13634, D13639–D13640; Turner Bequest CLXVI 24a–25, CLXVII 29a–30, 31c–32

Vol.I (1826): Title Page, Edinburgh Castle, 1822–5; see George IV Visit to Edinburgh 1822 Tour Introduction

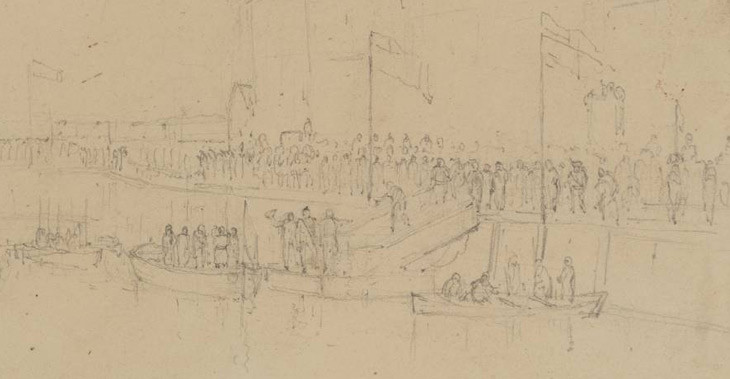

Vol.II (1826): Title Page, Edinburgh from Leith Harbour, circa 1825; see George IV Visit to Edinburgh 1822 Tour Introduction

In addition to these finished watercolours designs, Turner also made a number of related studies in watercolour. As has been mentioned, the Scotland and London sketchbook contains studies for the illustrations, and a related watercolour known as Crichton Castle, with Rainbow, circa 1818 (Yale Center for British Art, USA),28 may once have belonged to this sketchbook. On loose sheets, Turner made two colour beginnings of the Bass Rock before his final design (Tate D25327 and D35973; Turner Bequest CCLXIII 205 and CCCLXIV a 130), and in addition to a watercolour study for the Linlithgow Palace design (Tate D25316; Turner Bequest CCCLXIII 194), Katrina Thomson has identified a study for an alternative view of Linlithgow (Tate D25325; Turner Bequest CCLXIII 203).29

As mentioned above, two further watercolours that were engraved for other projects also resulted from sketches made on this tour: Newcastle-on-Tyne, circa 1823 – along with an associated study (Tate D25290; Turner Bequest CCLXIII) – for the Rivers of England, and Craigmillar Castle, circa 1833, for Scott’s Prose Works.

For all the ambition of the project, and the good will and enthusiasm of the shareholders and contributors, the Provincial Antiquities was not a success. Lizars expressed his concern in November 1820 in a letter to Blore, his fears summing up the flaws that would doom it to failure: ‘I fear the work is too great and too expensive to meet the purse of the public’.30 In June 1823, Blore reported the decision made at a shareholders’ meeting ‘to confine the work to ten Numbers; to prevent further expense and loss’.31 By this time he was finding it difficult to organise the distribution of plates and text, as artists and engravers were falling behind schedule, and he was forced to ask Scott to write general descriptions without seeing proofs of artists’ designs, a move that went against the integrity of the project.

In an attempt, perhaps, to reinvigorate the project and boost sales by adding contemporary interest, Scott commissioned Turner to make two vignette designs as frontispieces to the two volumes of 1826 bound edition of the Provincial Antiquities. Turner had returned to Edinburgh in 1822, perhaps at Scott’s suggestion, to see King George IV’s visit, and to make sketches for future paintings.32 Sketches collected on that tour informed two vignette illustrations. The Frontispiece for Volume One (watercolour, Tate D13748; Turner Bequest CLXVIII A) is a view of Edinburgh Castle showing the procession with the Regalia of Scotland,33 and the Frontispiece for Volume Two (watercolour, Tate D13749; Turner Bequest CLXVIII B) shows Sir Walter Scott welcoming the King to Scotland.34 During his journey to and from Edinburgh by sea Turner also got another chance to see the Bass Rock, making sketches that informed his watercolour design (see list above). This additional material, however, did not generate enough public interest to make further numbers of the Provincial Antiquities covering other areas of Scotland, and the project ended here.

As agreed in the contract, Walter Scott, in lieu of payment for his services, received some of the original designs for the publication, including eight of Turner’s ten watercolours (Bass Rock and Dunbar seem not to have gone to Scott).35 These eight were framed together in heavy oak from a tree felled on Scott’s estate, and remained during the author’s life in the breakfast room of Abbotsford. When A. J. Finberg saw them in the collection of Thomas Brocklebank, he criticised the ‘atrocious’ frame which he felt was ‘guaranteed to kill the effect of any water-colour drawings but the radiantly immortal ones for which it was made’, but noted that its protective curtain had ‘kept Turner’s beautiful work as fresh as when it was first executed’;36 they retain their colour and luminosity still.

The history of the publication is well documented in Gerald Finley, Landscapes of Memory: Turner as Illustrator to Scott, London 1980, pp.49–68; and Katrina Thomson, Turner and Sir Walter Scott: The Provincial Antiquities and Picturesque Scenery of Scotland, exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh 1999.

The approximate date is known because of a letter he wrote to the sculptor Francis Legatt Chantrey on 22 October, saying he hoped ‘to be in Edinburgh by this day week’ (Finley 1980, pp.51, 248 note 8), and by a letter from Edward Blore to Walter Scott of 20 October in which he wrote: ‘Turner... is about starting for Scotland for [the] purpose of preparing his Drawings’ (Blore to Scott, 20 October 1818, National Library of Scotland, MS 3889, folio 217, in Ibid.).

Francina Irwin points out that the Palmer Mail Coach reached Scotland from London in 60 hours with four passengers, (Francina Irwin, Andrew Wilton, Gerald Finley and others, Turner in Scotland, exhibition catalogue, Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museum 1982, p.7).

Eric Shanes, Turner’s Watercolour Explorations 1810–1842, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1997, p.63.

As Katrina Thomson has pointed out: ‘By the time Turner left for Scotland, the allocation of subjects between the various artists must have been virtually settled, for his sketchbooks contain little that is not pertinent to his final illustrations’ (Thomson 1999, pp.25–6).

Wilton 1979, p.433 no.1123. Wilton suggests that a sketch in the Abbotsford sketchbook (Tate D25971; CCLXVII 24a) is the basis of the design, but it has subsequently been identified as another location.

John Schetky informed his sister Jane that Turner had taken ‘sketches of Roslin, Borthwick and Dunbar Castles, but no one saw them except Walter Scott.’ (A. Fraser 1872, quoted in Finley 1980, p.54).

A ‘list of the Lothian subjects’ is included the letter from Edward Blore to Walter Scott (cited above), including all of the published sites and some that were never published. (Blore to Scott, 20 October 1818, in Finley 1980, pp.51, 248 note 8). Katrina Thomson also includes in her catalogue, a map of published and unpublished Provincial Antiquities sites (Thomson 1999, p.[14]).

Alexander J. Finberg, The Life of J.M.W. Turner, R.A. Second Edition, Revised, with a Supplement, by Hilda F. Finberg, revised ed., Oxford 1961, p.254.

W[illiam] G[eorge] Rawlinson, The Engraved Work of J.M.W. Turner, R.A., London 1908 and 1913, I, p.109no.193 (touched proof).

William Home Lizars letter to Edward Blore, 15 November 1820, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, MS 3029, folios 9v–10.

Edward Blore letter to Walter Scott, 13 June 1823, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, MS 3896, folios 195–195 verso.

See George IV Visit to Edinburgh 1822 Tour Introduction, and Gerald Finley, Turner and George the Fourth in Edinburgh 1822, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1981.

When the project was found to be floundering Scott offered to forego his part of the contract as a contribution towards the costs of maintaining the project: ‘I cannot possibly think of retaining the original drawings without making some compensation’, (Walter Scott to Edward Blore, 16 June 1823, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, MS 3029, folio 34, in Finley 1980, p.65).

How to cite

Thomas Ardill, ‘Tour of Scotland, 1818 for Scott’s Provincial Antiquities; sketchbooks 1818–20’, May 2008, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www