The First Meuse-Moselle Tour 1824

Sketch Map of the Meuse between Verdun and Mouzon; Other Notes and Sketches 1824

(from the Rivers Meuse and Moselle sketchbook)

From the entry

In early August of 1824 Turner embarked on his first major tour of the Rivers Meuse, Moselle (or Mosel, as it is known in Germany), and the Middle Rhine. He had explored the last of these rivers in some detail in 1817, just two years after the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the subsequent lifting of the embargo on European travel and trade. By 1824 Europe was enjoying a period of relative peace and ever expanding numbers of English tourists journeyed to the Continent for pleasure and curiosity. Travellers like Turner were afforded freer movement between countries and better access to sites of historical and literary interest, as well as (somewhat) improved transport links via waterways and stagecoach. Turner set off for the French coast on the morning of 10 August, returning to England just over a month later on 15 September. Upon his return, the artist’s formerly blank set of sketchbooks brimmed with fresh source material, his mind furnished with memories of newly discovered, war and time-altered landscapes from which ...

Rivers Meuse and Moselle Sketchbook

D18471–D18476; D19552–D19775; D19778–D19946; D19948–D20083; D40727–D40728

CCX 90–92a; CCXVI 1–270

D18471–D18476; D19552–D19775; D19778–D19946; D19948–D20083; D40727–D40728

CCX 90–92a; CCXVI 1–270

In early August of 1824 Turner embarked on his first major tour of the Rivers Meuse, Moselle (or Mosel, as it is known in Germany), and the Middle Rhine. He had explored the last of these rivers in some detail in 1817, just two years after the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the subsequent lifting of the embargo on European travel and trade. By 1824 Europe was enjoying a period of relative peace and ever expanding numbers of English tourists journeyed to the Continent for pleasure and curiosity. Travellers like Turner were afforded freer movement between countries and better access to sites of historical and literary interest, as well as (somewhat) improved transport links via waterways and stagecoach.

Turner set off for the French coast on the morning of 10 August, returning to England just over a month later on 15 September. Upon his return, the artist’s formerly blank set of sketchbooks brimmed with fresh source material, his mind furnished with memories of newly discovered, war and time-altered landscapes from which original paintings and drawings could develop. He recorded the 1824 tour in four sketchbooks: the Rivers Meuse and Moselle, the Huy and Dinant, the Trèves and Rhine, and finally the Moselle (or Rhine). Each offers the viewer a rich and varied pictorial record of the history, natural and human topography of the parts of Belgium, north-eastern France, western Germany and Luxembourg through which these three rivers flow.

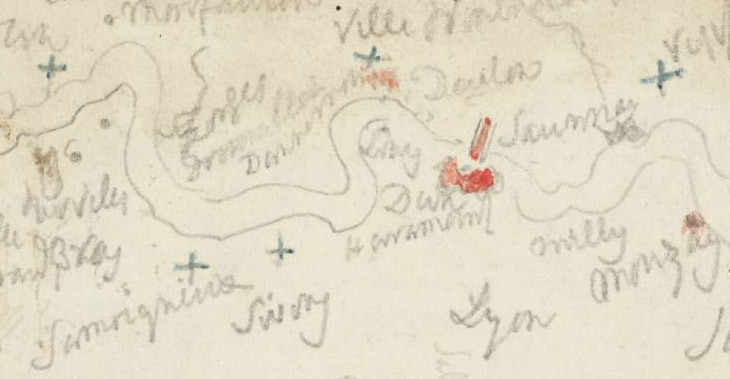

The first of the sketchbooks, the Rivers Meuse and Moselle, is the most detailed and descriptive of them all. It is the smallest of the four, scarcely bigger than a pocket book, but its two hundred and seventy pages are crammed with a wealth of visual and written information. The scope of its contents is owed to the fact that Turner used this sketchbook the most, employing it more or less throughout the duration of the tour. The other three sketchbooks were utilised individually at various places, but often in tandem with the Rivers Meuse and Moselle. A stout little book, Turner used the first nine of its leaves to write down preparatory notes and draw out sketch maps of the places he intended to visit between Germany’s Trier and Koblenz (Tate D19552–D19569; Turner Bequest CCXVI 1–9a). His information was sourced from the 1818 English translation of Alois Wilhelm Schreiber’s The Traveller’s Guide down the Rhine, a book which Turner himself owned. From it, the artist transcribed Schreiber’s potted histories of towns and cities on the Rhine, his recommendations of inns and taverns, his endorsements of natural, historical, and artistic sights, and advice on mileage. On folio 7 recto (Tate D19564; Turner Bequest CCXVI 7), for example, Turner makes note of:

Cardin Mt Town

Church Castle Monr Sontag Pictures

This is a shorthand transcription of Schreiber’s passage on the pretty market town of Carden, where, in addition to the Church of St Castor and the medieval Castle Treis, the visitor was able to see a collection of ‘very interesting pictures of the old German school’, belonging to the ‘ci-devant mayor, M. Sonntag’.1

Schreiber’s was a popular guide among polite members of British society. Despite European travel being a time consuming, often uncomfortable and rather expensive pursuit, Schreiber understood and profited from that fact that ‘the Continent is now become the fashionable resort of Englishmen’.2 His guidebook offered the genteel and curious a plethora of ‘information respecting the Manners, Customs, Soil, Produce, and Population of the Countries they may visit’, and also incorporated direction ‘to every object of Nature and Art which is worthy of particular notice’.3 Indeed, a puff in Rudolph Ackermann’s Repository advertises the Traveller’s Guide as:

minutely describing the modes of conveyance, the picturesque scenery, and every other object that can interest a stranger or facilitate his journey; illustrated by a large and correct map of the Rhine, by A. Schreiber, historiographer to his Royal Highness the Grand Duke of Baden.4

Turner’s transcribed notes must have surely come in handy, equipping him with useful local knowledge which enabled the artist to avoid some places (dull scenery, a lower class of romantic ruin, dodgy inns) and to save time for the best of what the rivers had to offer.

In addition to these written notes, Turner also inscribed a full timetable of his tour in the back of the Rivers Meuse and Moselle sketchbook (Tate D20080; Turner Bequest CCXVI 270). He had done the same in the Itinerary Rhine Tour sketchbook of 1817 (see Tate D12696; Turner Bequest CLIX 100). This is a rare and valuable document, recording the main towns and cities which the artist visited and the days on which he visited them. The itinerary informs us that Turner left England for Calais on Tuesday 10 August 1824. It tells us that he reached the Meuse at Liège on the 13th; that he headed east and joined the Moselle at Metz on 21 August; and that he arrived in Koblenz, Germany on 1 September to begin his navigation of the Rhine. We also know that Turner’s final day of travel was Tuesday 15 September, when he sailed from the French port of Calais back to England. It is difficult to be certain if Turner wrote the timetable all in one go or at intervals, after his tour was complete or during it. What is certain, however, is that the timetable enables us to be accurate about when sketches showing identifiable towns and cities were executed in each sketchbook: prized information for any Turner scholar and art historian.

The itinerary described:

On Wednesday 11 August Turner docked at Calais. Over the course of the following two days he travelled by diligence across northern France, making for the Belgian cities of Brussels and Liège. This early stage of the tour is documented in a series of swiftly executed and cursory jottings in the Rivers Meuse and Moselle sketchbook (see Tate D19570–D19591; Turner Bequest CCXVI 10–20a). These pages bare fluidly rendered depictions of sailing vessels, distant coastlines, cliffs, cloud studies, harbour scenes, and even a jotting of three rather mean-looking seagulls (Tate D19570; Turner Bequest CCXVI 10).

Arriving at Liège on 13 August, Turner met the first of the three major rivers he was to study: the Meuse. He took sketches which show it from various vantage points, such as the ancient Pont des Arches: a position which enabled him to draw the city’s historical and ecclesiastical monuments from the perspective of the waterway (Tate D19592, D19598–D19599, D19636–D19638; Turner Bequest CCXVI 21, 24–24a, 43a–44a). The seventeenth-century Maison Curtius appears in some of his sketches, as does Liège’s formidable citadel, the dome of St Andrew’s Church, and St Paul’s Cathedral. Turner also took quick records of life and labour at the bustling quayside, and of the elaborate Mosan Renaissance buildings lining the riverbank. At Liège Turner began to make use of another larger, horizontal format sketchbook, the Huy and Dinant, in order to draw more detailed studies and wide-angle views (Tate D20084, D20095–D20103; Turner Bequest CCXVII 1, 8–12). He employed this sketchbook and the Rivers Meuse and Moselle simultaneously, continuing to do so as he navigated the Meuse from Liège to the fortified Walloon city of Huy (see Tate D19622–D19635, D20087–D20093; Turner Bequest CCXVI 36–43, CCXVII 2a–6a). Of particular note among the drawings of Huy is Turner’s rendering of the apse and Bethlehem Portal of the city’s Church of Notre Dame (Tate D19630–D19631; Turner Bequest CCXVI 40–41). The artist studies these fourteenth-century reliefs from close proximity and in considerable detail, showing that he did indeed disembark his vessel from time to time to sketch on foot.

As he navigated the Meuse between Liège and Huy, Turner took a few moments to sketch some of the towns and landmarks on the banks of the river, including the village of Tilleur, the grandiose eighteenth-century Château at Chokier and the former Augustinian abbey at Flône, founded in 1075 (Tate D19611–D19621, D20085–D20086; Turner Bequest CCXVI 30a–35a, CCXVII 1a–2).5 From Huy, Turner travelled back downstream, in order to spend an extra day in Liège, before journeying upstream, in a southerly direction, toward Namur and Dinant.

This Wallonian stretch of the Meuse is lined with walls of mighty limestone cliffs which loom at soaring heights over the water. Turner recorded these lofty mineral structures in a series of sketches, drawing from his boat at mid-river (see, for example, Tate D19641–D19642, D19645–D19646; Turner Bequest CCXVI 46–46a, 48–48a). The same geology is described by the travel writer Bartholomew Stritch, who, in 1845, wrote that the cliffs left him feeling somewhat claustrophobically ‘walled in on both banks by towering and almost perpendicular piles of rock’.6 Despite the dizzying scale of the rocks, this fluvial landscape activated Stritch’s imagination. He writes that the ‘broken and crenelated summits’ of the cliffs:

assume to the eye, the forms of gigantic fortresses and vast feudal castles in ruins. As these rocks contain a large proportion of iron ore, the deep dark rusty hues brought out upon them by the action of the air and the rain, give them a peculiarly sombre and time-worn character, which is admirably contrasted by the soft verdure of the trees and the bright green of the meadows, hop grounds, and gardens in the vicinity. It is this striking contrast that forms the great charm of the scenery of the Meuse.7

Travelling by boat or barge, Turner would have experienced these great rusted ‘fortresses’ of rock from the very best of vantage points.

The fortified Belgian towns of Namur and Dinant were next on Turner’s itinerary; he spent three days exploring them from 16 to 18 August. Given their locations along the Meuse, each town held considerable strategic value during the Napoleonic Wars. Both were home to monumental citadels. Dinant’s was constructed by the Dutch between 1819 and 1821 whilst the French King Louis XIV engaged Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, his celebrated military engineer, to construct a fortress at Namur during the invasion of 1692.8 Turner studied the citadel at Namur from a number of vantage points, many of which incorporate the Sambre, a river which meets the Meuse directly below the fortress (see Tate D19643, D19647–D19650, D20104–D20108, D41508; Turner Bequest CCXVI 47, 49–50a, 12a–15).

Turner’s drawings of Dinant equally display its fortress to full effect, positioned as it is atop a ‘high chain of rocks, which rise almost perpendicularly’ from the riverbed.9 These are the words of Dudley Costello, a travel writer recounting experiences of Dinant in the 1840s. He noticed how the fortress dominated all the available ‘approaches to the town’, its scale appearing ‘to laugh a siege to scorn’.10 The fort was completed by the Dutch in 1821, although, as Cecilia Powell has pointed out, ‘it still retained the hoist used in its building, which brought the stone from the barges of the Meuse up to their final destination over 100 yards above’.11 The hoist can be seen in a detailed study in the Huy and Dinant sketchbook (Tate D20113; Turner Bequest CCXVII 19).

Notre Dame Cathedral stands directly at the foot of Dinant citadel, and in striking architectural contrast to it. A Gothic building, its tower is topped with a sixteenth-century belfry resembling a teardrop. The fortress and Cathedral form the central motif for the majority of Turner’s Dinant sketches. Drawing from the west bank of the Meuse, he was able to incorporate the medieval bridge, quayside, and boats moored at the banks as well as the two celebrated monuments. A further Dinantais landmark recorded by Turner is the Roche à Bayard, a gigantic monolith which stands a few moments south of the town (see Tate D19656–D19662, D20109–D20113; Turner Bequest CCXVI 53a–56a, CCXVII 16–19).

On 19 August Turner entered northern France and the Ardennes region, following the trajectory of the Meuse over the course of five days all the way to Verdun. His first stop was Givet, a township dominated by the extensive fourteenth-century Fort Charlemont. Established by Charles V in 1555, the Holy Roman Emperor employed the citadel as a defence against the French until Givet was formerly ceded to Louis XVI in 1699.12 It is recorded in the following drawings: Tate D19664–D19671, D20114; Turner Bequest CCXVI 57a–61, CCXVII 20, a number of which show that Turner explored the heights around Givet from the route to Anseremme on foot.13

Turner’s journey upstream took him next to Fumay and then to the communities of Mézières and Charleville (merged in 1966 to create Charleville-Mézières), see Tate D19639, D19681, D19683–D19685, D41009; Turner Bequest CCXVI 45, 66, 67–68. From there the artist travelled to Sedan and Verdun, both fortified with citadels by Vauban, before journeying cross-country in an easterly direction to meet the second major river he intended to study, the Moselle at Metz (Tate D19682, D19691–D19698, D19700–D19709, D19786; Turner Bequest CCXVI 66a, 71a–75, 76, 80, 80a, 118). Turner stayed at Metz for two days from 24 to 25 August. Rather than sketch the city itself, he appears to have spent much of his time at Ancy and Ars-sur-Moselle and Jouy-aux-Arches, which lie to the south of Metz. There he recorded the crumbling remains of ancient aqueducts built from the early second century AD for the purpose of channelling water to the city when Metz was known by its Roman name of Divodurum Mediomatricum, later Mettis.14

The next stop on Turner’s itinerary was Luxembourg, a city north of Metz carved into a network of plateaux and perpendicular gorges by the narrowly winding Alzette and Pétrusse Rivers (see Tate D19712–D19716; Turner Bequest CCXVI 82–84). The fact that the artist made a very small number of swift and cursory sketches of this city, and, for that matter, that he paid relatively little attention to the Meuse in the French Ardennes, could be owed to the fact that he was nearing the halfway point of the tour. Turner was perhaps preoccupied with continuing his study of the Moselle, which he soon was to re-join at the ancient German city of Trier.

Before attending to that leg of the tour, a series of rather chaotic ‘carriage sketches’, which Turner executed as he made his way towards Germany from Luxembourg by diligence (Tate D19712–D19716; Turner Bequest CCXVI 82–84), are worthy of note. More an assemblage of abbreviated, irregular marks, drifting, jagged, and curtailed lines, they are evidence of the artist’s attempts to record what he saw through the window or on the top deck of the diligence despite the bumpy ride.

Turner arrived at Trier on 27 August. There he largely surveyed and sketched the city from across the Moselle at Pallien, a location which afforded him the greatest number of vantage points from which to record Trier’s topography and sites of antiquarian and ecclesiastical interest. These include: the Porta Nigra, the ruins of the Imperial Baths, the Basilica, the Roman Bridge, the Cathedral of St Peter and the neighbouring Liebfrauenkirche and finally St Gangolf’s Church (see Tate D19725–D19744, D20115, D41509, D20141–D20142, D20145–D20146, D20148–D20154; Turner Bequest CCXVI 88a–98, CCXVII 21, CCXVIII 3–4, 7–8, 10–16). Turner employed the Rivers Meuse and Moselle sketchbook in tandem with two other books at Trier: the Huy and Dinant for one study of the city and the newly initiated Treves and Rhine roll sketchbook. In the Treves and Rhine we find the only colour drawings of the 1824 tour: views executed in watercolour, and in pencil and gouache on grey hand-tinted paper. That Turner produced two finished colour studies of Trier, and that he took time to record the city in such detail, implies that he took pleasure in his surroundings there. As Cecilia Powell writes, in the artist’s sketches and drawings of Trier ‘there is a sense not only of arrival and fulfilment but also of great enjoyment’.15

From Trier, Turner journeyed on by boat down the Moselle to Neumagen (29 August), then Trarbach (30th), Cochem (31st), finally disembarking at Koblenz on 1 September. He documented this stretch of the river in the Rivers Meuse and Moselle sketchbook and the Moselle (or Rhine), a roll sketchbook which was to be the fourth and final book of this tour. His records in the Rivers Meuse and Moselle are meticulous: characterised by their diminutive scale, detail, and sheer number (Tate D19744–D19756; Turner Bequest CCXVI 98–104). Each leaf is subdivided to accommodate up to twelve river scenes. Each view is rendered with precision in crisp line, and often labelled with the names of villages or with notes on colour or light. These sketches show that the artist must have ‘turned his head constantly’, Powell writes, ‘in order to catch the views both upstream and downstream before they changed and disappeared’.16 The majority of the sketches are individually numbered and some also display compass bearings, such as ‘WN’ for ‘West’ and ‘North’. By contrast, each view in the Moselle (or Rhine) sketchbook is a whole page study, rendered with less precision (Tate D20163–D20192, D41010; Turner Bequest CCXIX 2–31). They are executed on sheets prepared in the same manner as the Treves and Rhine sketchbook, where Turner first hand tinted the paper with grey wash. The views were then drawn on the grey pages only, with pencil and chalk as well as scratching out and blotting techniques to achieve highlights.

Powell writes that ‘sailing, drifting or being rowed down’ the river by boat was inevitably a slow process, though travelling by road was much slower. Turner, then, would have had plenty of time to study the river with care, travelling, as most tourists did, either by public passenger barge or privately chartered boat. A rapid steamer service from Trier to Koblenz was still over seventeen years away.

The scenery was spectacular, and ample compensation for the slow pace of transport. Bartholomew Stritch writes that the Moselle ‘assumes a bolder, more imposing, romantic, and feudal character’, once one passed the satellite villages around Trier.17 ‘The mountains’, he continues, ‘not only rise to a much greater height, but are more varied and wild in their outlines’ and the river, with its ‘abrupt and capricious sinuosities’, takes the ‘most bizarre and unexpected turnings and windings’.18 Stritch also describes the fertility of the mountains, their lower reaches used by locals to cultivate vines and to lay out a ‘rich succession of corn fields, orchards, and luxuriant meadows’.19

Each meander of the Moselle brought into view fruitful material for sketching, typically: ‘gay or romantic looking towns, or villages, each with its gothic church and graceful spire, and generally overlooked from some towering crag by the ruins of a feudal castle or knight-robber-hold’.20 One such community was Traben-Trarbach, dominated by the ruined Castle Grevenburg (Tate D19764–D19771, D20186, D20191; Turner Bequest CCXVI 108–111a, CCXIX 25, 30), or Bernkastel, a town ‘at the foot of a lofty hill’ presided over by the vestiges of Burg Landshut (Tate D19757–D19760, D20176–D20182, D20192; Turner Bequest CCXVI 104a–106, CCXIX 15–21, 31).21 Beilstein, another village ‘nestled at the foot of a rock’, was home to medieval stronghold Burg Metternich. It was comprised of ‘the ruins of a round tower, and a set of fortifications, surmounted by a square donjon keep’.22 Burg Metternich, for the traveller and novelist Michael Joseph Quin, constituted ‘one of the most picturesque memorials of chivalry to be seen on the Moselle’.23 Cochem, where Turner stayed a night on 31 August, was another old town picturesquely situated and overlooked by ‘the extensive ruins of two ancient castles’ upon surrounding heights (see Tate D19793–D19796; Turner Bequest CCXVI 121–123).24 Stritch writes that ‘the more distant of these’, the Reichsburg, was an imperial citadel, whose lofty towers and massive walls, still standing today, sufficiently denote its former strength and importance’.25

In addition to these fortifications, Turner drew various other landmarks celebrated for their beauty and history. These include: the ruins of the monastery at Wolf and the precipitous Gockelsburg (Tate D20185, D41010; Turner Bequest CCXIX 24), the Hermitage on the Michaelslei at Ürzig (D19761 – D19763, D20184; Turner Bequest CCXVI 106a – 107a, CCXIX 23), and the vestiges of the abbeys of Marienburg and Stuben (Tate D19773–D19782, D20163–D20165, D20172, D20187; Turner Bequest CCXVI 112a–116, CCXIX 2–4, 11, 26).

Between Cochem and Koblenz Turner drew exclusively in the Rivers Meuse and Moselle sketchbook, recording tiny but detailed views of ruined castles and handsome riverside hamlets (see Tate D19797–D19818; Turner Bequest CCXVI 123a–134). When the artist reached Koblenz on 1 September he began to use the Treves and Rhine sketchbook again, in addition to the Rivers Meuse and Moselle (see Tate D19819–D19828, D19830, D19837, D20139–D20140; Turner Bequest CCXVI 134a–139, 140, 143a, CCXIX 1–2, 23). A large and vibrant city, Koblenz, according to Bartholomew Stritch, was known for ‘the advantageous and beautiful position it occupies’ at the confluence of the Moselle and Rhine Rivers, for the ‘animation and bustle that pervade its quays’, and for the ‘immense extent of its multiplied fortifications’.26 The most famous of these was the citadel of Ehrenbreitstein, ‘cloud capt’ and ‘gigantic’, overlooking the exact point at which the two rivers meet on the Deutsches Eck headland.27 Built by the Prussians from 1817, by the time of Turner’s visit in 1824 Ehrenbreitstein was still in construction, though his sketches communicate its already intimidating scale and the ‘innumerable tiers of batteries’ fortifying the headland.28 A decade and more after it was finished, Stritch called the citadel ‘an impregnable bulwark against any attempts of the French upon that part of the Prussian dominions’, and indeed Ehrenbreitstein was only ever expanded and never attacked.29

During his stay at Koblenz Turner made a short detour south of the city, ‘probably on foot’, as Cecilia Powell writes, to Lahnstein where the Burg Lahneck and Schloss Stolzenfels guard the Rhine and Lahn Rivers (see Tate D19829–D19831, D19833–D19834, D20155–D20159; Turner Bequest CCXVI 139a–140a, 141a–142, CCXIX 17–22). Turner then travelled down the Rhine in a north-westerly direction towards Cologne. Employing the Rivers Meuse and Moselle sketchbook alone, he recorded the towns of Andernach and Hammerstein, the Rolandseck with its vine-clad hills and ruined medieval castle, the Seven Hills, and the quayside at Bonn, before making one cursory sketch of Cologne when he arrived there on Sunday 3 September (Tate D19838–D19844; Turner Bequest CCXVI 144–147).

This was in fact the sum of Turner’s investigations of the Rhine, and the commencement of the artist’s homeward journey. From Cologne, he travelled westward by diligence to the Belgian city of Liège, arriving there on 4 September (Tate D20060–D20064; Turner Bequest CCXVI 260a–262). Turner then made for Brussels, drawing aspects of the city in six sketches which include a study of its Parliament building: the Palais de la Nation (Tate D20067–D20072; Turner Bequest CCXVI 263a–270). Turner travelled to Ghent in the province of East Flanders on the 6th, before taking a canal boat via Bruges to Ostend, reaching the port on 7 September. As Powell notes, Turner’s swift progression through Belgium ‘led only to pages of disjointed scribbles and illegible notes dashed off at top speed’ (see Tate D19851–D19892, D20065–D20066; Turner Bequest CCXVI 149a–170a, 262a–263).30 The exception to this run of rather rough and nondescript sketches, however, is found on folio 154 verso: a drawing which records Turner’s own diligence jammed and teetering at an oblique angle in a ditch on the side of the road (Tate D19863; Turner Bequest CCXVI 154a). The overturned stagecoach, writes Turner, had to be ‘dug out’ with a single shovel by its drivers while passengers watched and waited: the vicissitudes of chartered travel.

From Ostend Turner journeyed west to the port of Dunkirk situated on the Channel, a few kilometres from the Belgian border. His sketches depict the sand dunes and the expansive beaches which characterise the coastal topography of this area. The artist also examined the town on foot, recording the medieval Tour du Leughenaer (or Liar’s Tower) converted into Dunkirk’s lighthouse in 1814, the Church of Saint-Eloi and the freestanding belfry (Tate D19910–D19920, D19941–D19942; Turner Bequest CCXVI 179–185, 195a–196). The major port city of Calais was next on Turner’s itinerary, a destination at the front lines of France’s conflict with the United Kingdom during the Napoleonic Wars. A relic from previous wars, the Fort Rouge (a seventeenth-century battery built out to sea) is present in a few of Turner’s Calais sketches; as is the Town Hall, the Church of Notre Dame, and the Tour de Guet (Tate D19922–D19927, D20083; Turner Bequest CCXVI 186–188a, 272).

On 10 September Turner made for Abbeville in the Picardie region of Northern France. A picturesque town located on the banks of the Somme, the artist drew street views there, scenes at the corn market and Grand Place, and studies of the Flamboyant Gothic Church of Saint-Vulfran (Tate D19929–D19940, D19943–D19950, D20116–D20117; Turner Bequest CCXVI 189a–195, 196a–200, CCXVII 22–23). Some of these drawings were developed into a design to illustrate Scott’s Prose Works, published over ten years later in 1836 (Tate impression T04763).

Travelling back towards the coast on 11 September, Turner passed through the towns of Le Tréport and Eu, taking a few hours there to draw the Château d’Eu and the Church of Notre Dame and St Lambert (Tate D19953–D19958; Turner Bequest CCXVI 201a–204). He arrived at Dieppe on the same day, beginning a period of intensive study of the city’s harbour, quays, jetties, and beaches (Tate D19959–D20033; Turner Bequest CCXVI 205–245a). When Turner left Dieppe on 12 September, he had amassed just under forty pages of sketches, many of which are exquisitely detailed. There are studies of the buildings which surround the harbour including the majestic sixteenth-century Hotel d’Anvers and medieval Church of Saint-Jacques, sketches of docked vessels and boats aground, records of fishermen and fishwives selling their daily catch, jottings of street scenes and signage, and even sketches of soldiers patrolling the ‘Douane’ (Customs House) and the ‘British Consulate’ (see Tate D19963–D20033; Turner Bequest CCXVI 207a–245a).

Before embarking on his return journey, Turner spent one final day at Abbeville and Calais. The artist left France for London on 15 September. Turner’s next full tour of the Meuse, Moselle and Middle Rhine was to take place fifteen years later in 1839, and he was to follow an almost identical itinerary to the one he had established in the summer of 1824.

Publishing and printmaking:

Having described the itinerary of Turner’s first Meuse-Moselle tour, it is important to address the question of why it took place. Whilst there is no doubt that travel brought the artist a great deal of pleasure and satisfaction, a tour of this scale represented a considerable investment of time and money. Owing to his now well-documented financial acumen, Turner most likely envisioned the 1824 tour as a professional venture to gather material for future projects and commissions. Cecilia Powell suggests that Turner may have responded to trends in contemporary publishing and printmaking, which looked favourably on Mosan and Rhenish subject matter, as motivation to undertake the journey. Wordsworth’s Memorials of a Tour on the Continent, 1820 (published 1822), for example, recounts the poet’s experience of the Meuse between Liège and Namur, as well as Bruges and Cologne. Powell also astutely notes that 1823 saw the death of Ann Radcliffe, author and pioneer of the Gothic novel. Radcliffe’s obituaries were filled with excerpts from her writings on the ‘Western Frontier of Germany’ and the Rhine which she navigated in the 1794.31 In addition, Sir Walter Scott’s Quentin Durward, a tale of a Scottish cadet in the service of the French King Louis XI, was published in 1823. Much of the story is set in Liège and the Ardennes as the plot unfolds around the longstanding rivalry between Louis and Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. The territories and castles of both the Burgundian court and of the French King’s ally, William de la Marck, are included in Turner’s sketch maps in the Rivers Meuse and Moselle sketchbook (see Tate D19558, D19560; Turner Bequest CCXVI 4, 5). Turner and Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832) kept a close professional association following their first meeting in 1818 when the artist was engaged to illustrate Scott’s Provincial Antiquities of Scotland.

Most significant of all of these publications is perhaps Samuel Prout’s lithographs Illustrations of the Rhine, published by Rudolph Ackerman between 1822 and 1824, and the commercially successful Scenery of the Rhine, Belgium and Holland by Captain Robert Batty, the first part of which was released in May 1824 two months before Turner set off for the Continent. As Cecilia Powell writes:

Turner could hardly fail to have taken note of [Batty’s] publication since it was only a very short time since its companion volume, Batty’s Italian Scenery... and his own very similar work for James Hakewill’s Picturesque Tour of Italy (1818–20) had run a neck-and-neck race in competition for the public’s attention.32

These rival publications notwithstanding, the year 1824 represented an equally busy period in Turner’s output. Among his other projects, the artist was in the middle of producing a series of designs for W.B. Cooke’s large-scale engraving project The Rivers of England, published in seven instalments between 1823 and 1827. Though the project was never finished and came to an abrupt and rather acrimonious end, by August 1824, it ‘still seemed set fair to succeed’.33 Cooke may have considered the possibility and profitability of a complimentary engraving project, this time depicting selected Continental rivers, to follow the publication of the English. A market for images of northern European river landscapes was clearly in place, should Turner have wished to contribute to it.

In the end, no printmaking project was to emerge from the first Meuse-Moselle tour. While Turner’s journey was highly productive in terms of pencil sketches, it lead to only one, though significant, finished work. This was the oil painting Harbour of Dieppe (Changement de Domicile), exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1825.34 Turner had been commissioned to produce this picture by John Broadhurst, before he had departed for Europe. The commission explains why Turner studied Dieppe with such intensity over 11 and 12 September, and accounts for why this last section of the tour took place at all. Harbour of Dieppe was to be followed by Cologne, The Arrival of a Packet Boat, Evening, a second Broadhurst commission, the two displayed as companion pieces.35 The product of sketches taken by Turner on an 1825 tour to Holland and the Rhine, Cologne was exhibited at the Royal Academy a year later in 1826.

The Matter of Dating:

In 1909 A.J. Finberg proposed that this tour be dated to 1826, noting that the date was indeed ‘liable to alteration should fresh facts come to light’. Though new facts failed to emerge, existing knowledge of the tour and Turner’s oeuvre was reassessed. Dr Cecilia Powell was the first scholar to undertake this task. Powell’s findings are laid out in her catalogue to the 1991 Tate exhibition Turner’s Rivers of Europe: The Rhine, Meuse and Mosel. Her research led to the re-dating of not only this but also of the second Meuse-Moselle tour of 1839.

In her review of Turner’s inscribed itinerary at the back of the Rivers Meuse and Moselle sketchbook she was able to demonstrate that the dated destinations listed by the artist could only correspond to 1824 and not to the dates supplied by Finberg which range wildly from 1818 to 1829 (see Tate D20080; Turner Bequest CCXVI 270 for a full explanation).36 This discovery notwithstanding, Powell writes that the ‘strongest proof’ of Turner’s tour taking place in 1824 is the presence, in the same sketchbook (CCXVI), of a large number of preparatory sketches which clearly form the basis of the important oil painting Harbour of Dieppe (Changement de Domicile). It had previously been stated that Turner used drawings taken at Dieppe in 1821 to produce this painting, but those are comparatively few in number and lack the range and meticulous detail of the 1824 drawings. Such a large and complex painting could only be the product of these extensive preparatory sketches, and, indeed aspects of those sketches can be identified clearly in the finished piece.

With a new date of 1824 established, then, other matters become clarified. The financial calculations inscribed at the rear of the Rivers Meuse and Moselle sketchbook dated from September 1823 to July 1824 no longer appear as anomalous as they once had when the tour was assigned to 1826 (see Tate D20080; Turner Bequest CCXVI 270). In addition, clarifications were made regarding the 1826 tour of the Loire, undertaken as part of Turner’s study for the Rivers of France project (1833–35).37 As Powell writes:

it used to be postulated that this visit was squeezed into the later part of September and early October 1826, after the Meuse-Mosel tour was over, though it has never been satisfactorily explained precisely how Turner reached the Loire from Calais, nor why such an important and disparate French tour should have been tacked on to the other one with almost indecent haste.38

With the Meuse-Moselle tour re-dated to 1824, Turner’s journey down the Loire could take place at an ‘ordinary’ and ‘leisurely pace’, and not, as has been stated as late as 2006, at the tail end of the Meuse-Moselle tour.39

Alois Wilhelm Schreiber, The travellers’ guide down the Rhine: exhibiting the course of that river from Schaffhausen to Holland, and describing the Moselle from Coblentz to Treves with an account of the cities, towns, villages, prospects, etc, London 1825, p.177.

Rudolph Ackermann’s Repository of arts, literature, commerce, manufactures, fashions, and politics, vol.V, 1818, p.251

‘Abbey of Flône’, Belgian Tourist Office, http://www.opt.be/informations/tourist_attractions_flone__abbey_of_flone/en/V/48809.html , accessed 27 August 2014.

Bartholomew Stritch, The Meuse, the Moselle, and the Rhine; or, A six weeks’ tour through the finest river scenery in Europe, by B.S, London 1845, p.17.

Dudley Costello, A tour through the valley of the Meuse: with the legends of the Walloon country and the Ardennes, 2nd edition, London 1846, p.190.

Metz (France), Roman Aqueducts, accessed 28 August 2014, http://www.romanaqueducts.info/aquasite/metz

Bartholomew Stritch, The Meuse, the Moselle, and the Rhine; or, A six weeks’ tour through the finest river scenery in Europe, by B.S, London 1845, p.47.

Michael Joseph Quin, Steam voyages on the Seine, the Moselle, & the Rhine: with railroad visits to the principal cities of Belgium, London 1843, p.60.

Bartholomew Stritch, The Meuse, the Moselle, and the Rhine; or, A six weeks’ tour through the finest river scenery in Europe, by B.S, London 1845, p.57.

See Ann Radcliffe, A journey made in the summer of 1794, through Holland and the western frontier of Germany: with a return down the Rhine: to which are added Observations during a tour to the lakes of Lancashire, Westmoreland, and Cumberland, London 1795.

Powell 1991, pp.38–9 and Finberg 1909, vol.II, p.681 (see asterisked note at the bottom of the page in Finberg).

How to cite

Alice Rylance-Watson, ‘The First Meuse-Moselle Tour 1824’, June 2014, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, April 2015, https://www