Sketchbooks from the Tour to Switzerland 1802

From the entry

These sketchbooks were used in 1802, during Turner’s first tour beyond British shores, through France to Switzerland. Other drawings and watercolours made during or after the tour are treated separately. The war with revolutionary France that broke out in 1793 had deprived Turner’s generation of travel to continental Europe but the Treaty of Amiens of 28 March 1802 opened a window of opportunity. Turner was among the swarm of artists, travellers and adventurers who crossed the Channel in the summer of 1802. Most went no further than Paris and for artists, the main attraction was the ‘Musée Central des Arts’ in the Louvre. Turner’s tour to the Alps was exceptional, arguably the formative experience of his life – even more than his first visit to Italy in 1819, itself delayed by the resumption of the Napoleonic War – and provided him with material for years to come. For his trip to Paris, Turner was funded by a consortium of aristocratic patrons who thought he ...

References

These sketchbooks were used in 1802, during Turner’s first tour beyond British shores, through France to Switzerland. Other drawings and watercolours made during or after the tour are treated separately.

The war with revolutionary France that broke out in 1793 had deprived Turner’s generation of travel to continental Europe but the Treaty of Amiens of 28 March 1802 opened a window of opportunity. Turner was among the swarm of artists, travellers and adventurers who crossed the Channel in the summer of 1802. Most went no further than Paris and for artists, the main attraction was the ‘Musée Central des Arts’ in the Louvre. Turner’s tour to the Alps was exceptional, arguably the formative experience of his life – even more than his first visit to Italy in 1819, itself delayed by the resumption of the Napoleonic War – and provided him with material for years to come.

For his trip to Paris, Turner was funded by a consortium of aristocratic patrons who thought he would benefit from seeing the pictures in the Louvre. In 1857, it was said that Lord Yarborough financed the trip with ‘two other noblemen’1 so that Turner could ‘study on the Continent the works of the great masters’. Lord Yarborough had known Turner since at least 1798, stood as a referee for the artist’s passport in 1802 and bought an impressive outcome of his tour, the large painting Festival of the Opening of the Vintage of Macon (Sheffield Galleries & Musuems Trust)2 exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1803. Turner’s other benefactors probably included the Earl of Darlington, and perhaps the Duke of Bridgewater who had commissioned Turner’s Dutch Boats in a Gale (private collection; on loan to the National Gallery, London)3 as a companion for a picture by Willem van de Velde in 1801, or (though not a nobleman) Walter Fawkes who had visited Switzerland as a young man and would in due course acquire the largest single collection of Turner’s watercolours and other works based on the 1802 tour.

On 14 July 1802, the artist Joseph Farington reported in his diary: ‘Turner sets off for Paris tomorrow on his way to Swisserland’.4 If Fawkes was among his sponsors, his brief might never have been restricted to the study of Old Masters in Paris as some sources claimed. But another possibility is that the main part of the tour, to Switzerland, was financed separately by the young gentleman from Co. Durham, Newbey Lowson, whose identity and role as its ‘paymaster’ have been uncovered by Cecilia Powell.5 Lowson and Turner travelled to the mountains together and Turner gave his companion drawing lessons en route. As Lord Darlington stood as referee for Lowson’s passport and the two men were friends who visited the Continent together in 1816, the Earl might have contributed to the costs of the entire trip with Lowson dispensing his funds as well as his own. But it was also normal for such a man as Lowson to employ an artist and drawing master on his foreign travels.

It is not known whether Turner and Lowson travelled together from London or met in Paris but from that point their interests coincided, to Turner’s advantage. In Paris, a small carriage, a cabriolet, was bought for 32 guineas (it was returned and sold on the way back) and a Swiss servant and guide was hired; he was paid five livres a day and covered his own expenses. The cabriolet enabled Turner to carry larger and bulkier sketchbooks than would have been practical on foot. He brought the Fonthill sketchbook that had already seen use in England but still had spare pages (see below), and another large new one that would become the St Gothard and Mont Blanc as well as smaller books, soon to be Small Calais Pier and Studies in the Louvre. In Paris he bought the future France, Savoy, Piedmont book from Coiffier’s shop and the Grenoble from the Papeterie du Marais. Later, in Berne, he would top up his supply.

Turner had a stormy landing in Calais and had to wade ashore through the breakers. His approach and first sights of the port and its surroundings were jotted down in his Small Calais Pier sketchbook; when Turner got back to England, he drew more elaborate versions of the landing, worked up with pictures in mind, in a larger book, Calais Pier (Tate D04902–D05072; Turner Bequest LXXXI). Once in Paris, he probably made a quick reconnoitre of the Louvre but his first stay was short and mainly given over to preparations for the journey ahead. Even so it is striking that he made no drawings at all – even thumbnail sketches – of the city and ignored it again during his longer stay on the way back. Moving south across France he made only quick outlines, from the coach or during roadside stops, in his France, Savoy, Piedmont book and later described the country as far as Lyon as ‘very bad’.6 Nevertheless, his sketches around Mâcon would be transformed in the Opening of the Vintage the following year.

Turner’s itinerary in 1802 has been covered in detail elsewhere, notably by David Hill,7 and can be followed in published maps. Here it is summarised mainly in relation to his choice of sketchbooks, with a few examples of their contents cited. From these it is clear that the route only really began to interest Turner as he approached Grenoble from Lyon along the Isère valley and he began using the larger leaves of his Grenoble book (for example Tate D04513; Turner Bequest LXXIV 20) and made his first drawing in the larger St Gothard and Mont Blanc book (D04618; Turner Bequest LXXV 26) which he had been reserving for mountain scenery. He drew the city and fort, the Rivers Drac and Isère and nearby mountains and made an excursion into the Grande Chartreuse, which he found ‘abounding with romantic matter’8 and made the subject of a number of leaves in the Grenoble book. After this picturesque detour he turned north along the Isère valley to Geneva, with few stops for drawing – an exception being at Rumilly near Annecy where he drew a tower and mill beside the River Néphaz on another Grenoble leaf (D04532; Turner Bequest LXXIV 39).

After a pause at Geneva, Turner and Lowson continued south-east along the Arve valley on the way to Chamonix and Mont Blanc. At Bonneville, then regarded as a gateway to the Alps, Turner made drawings in the St Gothard and Mont Blanc book (for example Tate D04599; Turner Bequest LXXV 7) that proved to be among the most productive of paintings and watercolours of any he made during his tour. In the same book, he drew St Martin (Tate D04601; Turner Bequest LXXV 9) and Sallanches (Tate D04603; Turner Bequest LXXV 11), the Chamonix glaciers (Tate D04613; Turner Bequest LXXV 21) and the Mont Blanc massif (Tate D04610; Turner Bequest LXXV 18) before beginning the hard slog on foot over the Col de Voza down to Bionnassay and Les Contamines. A view of Les Contamines with dawn breaking over Mont Blanc (Tate D04616; LXXV 24) marks a rare pause during this arduous stretch of the journey, before continuing over the Col du Bonhomme and Col de la Seigne down the Val Veni to Courmayeur and the Val d’Aosta. During this long trek Turner kept his most of his sketchbooks packed except for the compact France, Savoy, Piedmont which was small enough to keep in his pocket and convenient for quick sketches. He used it on the way to Mont Blanc and as far as Courmayeur by which point the Grenoble book was in use again. The latter contains fine views of Aosta (for example Tate D04502, D04503; Turner Bequest LXXIV 10, 11).

From Aosta there was more hard climbing, over the Great Saint Bernard Pass where the ‘Road & accommodations’ were ‘very bad’9 and Turner confined his drawing, again in the Grenoble book, mainly to the summit and the famous Augustinian hospice that ministered to travellers. His view of the hospice across the tiny lake, with Mont Vélan in the distance (D04584; Turner Bequest LXXIV 55) probably includes a rare glimpse of himself, Lowson and their guide. The comforts of the cabriolet had been lacking since Geneva, as it had been sent on to meet them at Martigny. Various drawings in the Grenoble book suggest an extended pause in the ancient town beside the River Drance; as well as the castle of La Bâtiaz and the river (Tate D04494; Turner Bequest LXXIV 2) he drew a procession on a saint’s feast day (Tate D04580; Turner Bequest LXXIV 87). Thence the route was north to Lake Geneva past the castle of Chillon (Tate D04535; Turner Bequest LXXIV 42) and Vevay to Lausanne, on to Avenches and then east to Berne.

At Berne, Turner bought three new sketchbooks. One, Swiss Figures, was used for studies of figures and Swiss costume, probably mainly in the city of which he seems otherwise to have only made only one drawing. Another, Lake Thun, came into use as he reached Thun while Rhine, Strassburg and Oxford saw service from the same area and during the later stages of the tour as well as in England on his return. At Thun, which he reached along the Aare valley from Berne, he drew the castle and church in St Gothard and Mont Blanc book (Tate D04622; Turner Bequest LXXV 30). Once again, the cabriolet had to be sent on ahead, this time to Unterseen at the eastern end of Lake Thun while the travellers made the journey by boat, rowed by ferrymen from Thun.

At the landing-place at Neuhaus, Turner watched ferries arriving and departing and the approach of a thunderstorm. Then, Turner and Lowson set off via Lauterbrunnen to Grindelwald where Turner drew the glaciers and forests and the looming Eiger in his Grenoble book (Tate D04537; Turner Bequest LXXIV 44). Here too the cabriolet was sent ahead to Brienz while the travellers took to mule and foot to cross the Great Scheidegg to Meiringen and to explore the scenery around the Reichenbach Falls. A day’s trip by boat along Lake Brienz to see the ruined castle of Ringgenberg is recorded in a number of drawings; those in the Rhine, Strassburg and Oxford book were presumably made in the boat while others in Grenoble and St Gothard and Mont Blanc (for example Tate D04539; Turner Bequest LXXIV 46 and Tate D04648; Turner Bequest LXXV 56) were made or elaborated afterwards.

From Brienz the party set off through the Brünig Pass to Lucerne and east around the lake to Fluelen. On a boat tour of the lake, Turner had his first sight of the classic scenery around Brunnen, the Bay of Uri and the Rigi mountain that would be favourite subjects in the 1840s. The climax of his mountain tour was a trip along the Reuss valley past Altdorf, Amsteg and Wassen into the St Gotthard Pass. The spectacular scenery, the epitome of the mountain Sublime and the site of recent fighting in 1799 when a Russian army under General Suvorov had briefly put the occupying French to rout, made this fruitful terrain for pictures. The large St Gothard and Mont Blanc book, generally kept for the grandest mountain scenery, now came into its own. The drawings, if begun on the spot, were also worked up with watercolour and gouache and subjects like the Devil’s Bridge (for example Tate D04625; Turner Bequest LXXV 33) were to translate directly into finished works.

Now unable to continue further, the group retraced its steps and set off homewards, north to Zug and Zurich, along the River Limmat past Baden to the junction with the Rhine. There was a diversion eastwards to Schaffhausen and the Rhine Falls, and then it was back again, continuing east to Laufenburg and Basle. Turner now added some final drawings to his old Fonthill book. The rest of the journey is documented in the Lake Thun and Rhine, Strassburg and Oxford books, the last of which was also used during a visit to Oxford, perhaps at the end of 1802 or the following year. But there was still important work to be done. Pausing for longer in Paris on the return journey, Turner was able to fulfil his obligations in the Louvre. He had kept a sketchbook aside, its leaves pre-washed with a grey tone as a ground for the richly-coloured copies he expected to make. As well as copies, Studies in the Louvre contains lengthy notes, commentaries and diagrams of the colouring of the pictures he saw. All but one were by Old Masters. Turner shared the contemporary British dislike of the current French school epitomised by Jacques-Louis David. In this, accumulated wartime prejudice doubtless played a part; it may also have accounted for his continuing indifference to the enemy capital itself, for in drawings made on later visits he seems enraptured of its beauty and vitality.

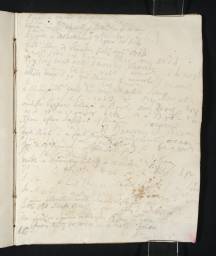

In the Louvre, Turner met his London colleague Farington, who recorded the traveller’s impressions in his diary. On 30 September, Turner told him that the ‘lines of the Landscape features in Switzerland [are] rather broken, but there are very fine parts’. On 1 October he spoke at greater length: ‘The Grand Chartreuse is fine; – so is Grindelwald... The trees in Switzerland are bad for a painter, – fragments and precipices very romantic, and strikingly grand. The Country on the whole surpasses Wales, and Scotland too...The weather was very fine: He saw very fine Thunder Storms among the Mountains’. Switzerland was in ‘a very troubled state’ but the people were ‘well inclined’ towards the British. He experienced ‘much fatigue from walking, and ...bad living and lodgings’.10 Back in London on 22 November, Turner showed Farington drawings made on his tour, with a running commentary and further remarks on the scenery: ‘Walnut trees in Switzerland &c very fine. N[icolas]. Poussin studied from them.– Houses in Switzerland bad forms, – tiles abominable red colour... Most of sketches slight on the spot, but touched up since many of them with liquid white, and black chalk’.11

From Farington’s description, these drawings were mainly from the Grenoble and St Gothard and Mont Blanc sketchbooks. As well as working them up with gouache and chalk, Turner may already have begun to separate the best sheets and mount them in the album in which they were found at his death. Composed of French paper, and leather-bound, this had presumably been acquired by Turner to display his best drawings in the order of the tour. Perhaps it was a cast-off from the library of one of the sponsors of his tour. Farington’s list of the subjects it contained – ‘Lyons, Grenoble, Defile of the Grand & Petit Chartreuse... Chamonix, of Mont Blanc etc, – of Aost, – St Bernard etc’ – follows Turner’s route and suggests they were placed in topographical order. We can also infer that Turner’s selection began mainly with drawings from Grenoble and went on to combine them with leaves from St Gothard and Mont Blanc. Labelled with their titles, they could be shown to prospective clients who might order finished versions in oil or watercolour.

When Ruskin came to sort through the Turner Bequest, he found the album as the artist had left it, ‘mounted in a more orderly fashion than, as far as I know, he ever achieved in business of this kind... the title was, however, written beneath each subject in Turner’s hand, and in Turner’s French’.12 Ruskin claimed that Turner had sold the album and bought it back, but it seems highly unlikely that he would part with such a resource at all. While Turner had broken into his sketchbooks to create a prime selection, ordered and described, Ruskin now undid it. He cut the drawings from the album, intending to exhibit many of them, but also removed Turner’s labels which he set aside in parcels. These survive today, in a condition more perplexing than helpful. In the case of some 109 inscribed labels relating to Grenoble drawings, Ruskin kept no record of which applied to which. He took more pains with another set, evidently originally attached to some of Turner’s St Gothard and Mont Blanc selections; these he labelled ‘Titles of the Great Chamonix Series’ and numbered. About half of numbers correspond to those on the drawings, but the relationship is frustratingly incomplete. Overall, the damage done can hardly be exaggerated. At a stroke, many subjects lost their identity and the taxonomy that Turner – uniquely, as Ruskin himself acknowledged – had created for his drawings was destroyed. In this catalogue, some attempt is made to reunite drawings with Turner’s labels, but it remains a work in progress.

Ruskin did not stop here. He broke up the Lake Thun and Rhine, Strassburg and Oxford sketchbooks, keeping no complete record of their order of contents. Noting that the former ‘merely’ showed ‘on how little he [Turner] depended for reminiscence of scenery’, he destroyed the integrity of books that received Turner’s first impressions of the later stages of his tour, recorded as they occurred day to day. From Swiss Figures he seems to have removed or disposed of some leaves, perhaps because they went further than a remaining subject in depicting the artist’s sexual life (or imagination). Today, France, Savoy, Piedmont is the only scenic sketchbook from the 1802 tour to remain intact, probably because Ruskin found little interest in its depictions of scenery across France and on the way to the mountains but nothing to object to either. The dismembered books were rebound in 1934, but in random order. Today, some leaves remain or have been bound back in the Fonthill and St Gothard and Mont Blanc books while others are mounted separately.

The drawings from Grenoble present the most complicated case. This series is referred to here, as elsewhere, as a sketchbook for want of a better name, but it is unclear whether it was ever a single book or rather a series of loose leaves kept together in paper wrappers. About sixty of them seem to have been mounted in Turner’s album; another thirty-five were found loose by Ruskin and described by him as ‘rubbish’, reflecting (albeit in characteristically extreme terms) the problems presented by the series as a whole. The drawings are distinct technically from others made on the tour but also fall into two groups. The majority (presumably those destined for Turner’s album) are worked up with chalk and white gouache over pencil, and show evidence of work in the studio as well as on the spot. They develop the monochrome graphic style of Turner’s ‘Scottish Pencils’ of 1801 which can ultimately be traced back to Richard Wilson. But there are also slighter outlines. In some cases the same composition exists in both types, and one wonders if these duplicate subjects were not somehow connected with the tuition Turner was giving to Lowson, or intended to furnish his ‘paymaster’ with his own record of the tour. It certainly seems unlikely that, as Turner’s early biographer Walter Thornbury claimed, Turner could have ‘imposed’ the condition that Lowson ‘never sketched any view of his own selection’, or that Turner ‘did not show his companion a single sketch’.13

Much as the break-up of Turner’s 1802 sketchbooks and album is to be regretted, it has it least ensured that drawings from them have been widely exhibited, from the earliest displays of the Bequest till today. As a result, the transforming impact of Continental and alpine scenery on Turner’s art and imagination in 1802 has long been recognised, from primary sources as much as from the paintings and exhibition watercolours that resulted from them.

Additional material:

Further views, mainly of Laufenburg and Schaffhausen, are in the Fonthill sketchbook (Tate D02203–D02208, D02229–D02233; Turner Bequest XLVII 26–31, 52–6) which Turner must have carried with him but had already used prior to his tour.

Acknowledgements:

Thanks are due to David Hill, whose published research on the 1802 tour, identifications of subject matter, site photographs and personal comments and advice have been invaluable. Peter Bower conducted ground-breaking research on the papers used for the 1802 sketchbooks. Andrew Wilton has given wise advice while Léonard Gianadda provided a welcome opportunity for some of the drawings made in 1802 to return to Switzerland for a showing at the Fondation Pierre Gianadda, Martigny, and generous hospitality. Thanks also go to Lombard Odier & Cie, Geneva.

Martin Butlin and Evelyn Joll, The Paintings of J.M.W. Turner, revised ed., New Haven and London 1984, pp.36–7 no.47 (pl.55).

Kenneth Garlick and Angus Macintyre eds., The Diary of Joseph Farington, vol.V, New Haven and London 1979, p.1797.

John Ruskin, Catalogue of the Sketches and Drawings by J.M.W. Turner R.A. Exhibited at Marlborough House in the Year 1857–8, London 1858, pp.25–6.

How to cite

David Blayney Brown, ‘Sketchbooks from the Tour to Switzerland 1802’, January 2010, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www