Turner Bequest CVIII 1–91a

Sketchbook bound in boards, covered in reddish-brown leather with blind-stamped decorative borders and a brass clasp; leather pencil loop along full length of bottom edge of back cover; bellows-type pocket inside front cover

91 leaves and pastedowns of white wove Whatman paper; various sheets watermarked ‘J Whatman | 1808’; page size 88 x 115 mm

Inscribed by Turner ‘56–’ on label (now lost, but presumably once glued to the spine)

Numbered 375 as part of the Turner Schedule in 1854 and endorsed by the Executors of the Turner Bequest inside front cover (D07353)

91 leaves and pastedowns of white wove Whatman paper; various sheets watermarked ‘J Whatman | 1808’; page size 88 x 115 mm

Inscribed by Turner ‘56–’ on label (now lost, but presumably once glued to the spine)

Numbered 375 as part of the Turner Schedule in 1854 and endorsed by the Executors of the Turner Bequest inside front cover (D07353)

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Exhibition history

References

Turner was elected the Royal Academy’s Professor of Perspective late in 1807, delivering his first course of lectures in 1811.1 The Perspective sketchbook was dated to about 1809 by Finberg in his Turner Bequest Inventory, presumably on the basis of its 1808 watermarks and accounts dated 1809 inside the back cover (D07354).2 Maurice Davies has relayed Jerrold Ziff’s research from the latter’s unpublished article, ‘The Writing and Dating of Turner’s First Perspective Lecture’: that the first draft of Turner’s perspective lectures was written after February 1809 may be deduced from a reference to a fire in London that month, and notes from the present sketchbook were subsequently added to the draft.3

A concordance given below divides the complex contents of the sketchbook into various categories: not only extensive notes on perspective and related optical issues, but also a few sketches, and Turner’s own original poetry and notes, making it among the richest repositories of Turner’s writings in the Bequest – as James Hamilton puts it, ‘buzzing with Turner’s own and other people’s ideas’.4 Ziff has suggested that Turner’s ‘poetical efforts and his research’ were ‘partially related’ activities.5 Davies has explored Turner’s response to each of his sources from the sixteenth century onwards, many of which were noted in the Perspective sketchbook.6 Related notes from other sources are to be found in the Greenwich, Frittlewell and Windmill and Lock sketchbooks of about the same period (Tate; Turner Bequest CII, CXII, CXIV).7

Turner’s research informed the extensive, complex manuscripts for the lectures themselves8 and the large diagrams with which he illustrated them (Tate; Turner Bequest CXCV). What Davies calls the ‘Preliminary Version’ of Turner’s notes on the historical sources on perspective (about 1809) is taken from the Perspective sketchbook and notes from Kirby in the Windmill and Lock sketchbook, in the form of an ‘unfinished series of small sketch diagrams, after various earlier writers, and list of treatises’, although Turner did not incorporate several of the methods for showing a cube in perspective which he had copied into the present sketchbook.9

Davies has described Turner as ‘[m]ore ambitious than anyone before him’ in his research on previous publications and methods.10 However, he conducted parts of his survey ‘superficially’, sometimes only copying one diagram from a book if it attracted him visually (particularly if the text was not in English), quoting from secondary sources to imply wider reading, and misinterpreting some sources.11

As the sketchbook remains in the order described and numbered by Finberg, no overall concordance is necessary. The various strands of material are intermingled, so for clarity they are grouped below as drawings, texts and diagrams; the numbering of the sections here is only for cross-reference and is not refererred to in catalogue entries for individual pages.

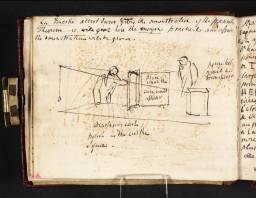

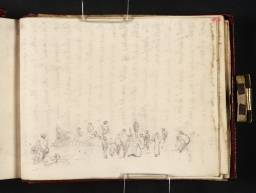

1. Drawings

For the fullest general account see Maurice Davies, Turner as Professor: The Artist and Linear Perspective, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1992, pp.15, 31 and throughout (Davies’s occasional references in his 1992 publication to pages of the Perspective sketchbook will be found in the relevant individual entries of the present catalogue).

See chapter 3, ‘Turner’s History of Sixteenth- and Seventeenth Century Methods of Perspective’, in Davies 1994, pp.73–106; and pp.287–9 for identifications of perspective-related notes and diagrams in folio sequence, some previously identified in Ziff 1984 (both sources cited here in relevant entries).

Turner, ‘Royal Academy Lectures’, circa 1807–38, Department of Western Manuscripts, British Library, London, ADD MS 46151.

Conventional riverside landscape drawings, mostly with figures:

More diagrammatic landscape drawings, several involving boats, demonstrating perspective in relation to light, shadows and reflections in water:

folios 7 recto (D07366); and four interspersed in the sequence of notes towards the end of the sketchbook, set out in section 4 below

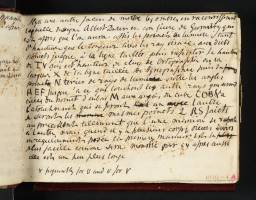

2. Notes from Lomazzo 1598

Ziff has established and Davies has confirmed that the most extensive passages of notes in the sketchbook derive from Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo’s Tracte Containing the Artes of Curious Paintinge Carvinge & Buildinge,12 published at Oxford in 1598 in a translation from the Italian by Richard Haydocke (1569/70–circa 1642),13 then studying medicine at Oxford University.14 Lomazzo (1538–1600), a painter and writer from Milan, published his Trattato dell’arte de la pittura there in 1584, divided into seven books on topics including theoretical and practical perspective (the fifth and sixth books),15 although Haydocke only translated the first five.16

As with his other sources (listed in section 3 below), Turner probably consulted the copy at the British Museum, since transferred to the British Library, London. Many of his notes from Lomazzo concern the art histories of ancient Greece and Rome and the Renaissance, which Ziff describes as ‘distractions’ and ‘a most remarkable irrelevancy’17 in terms of Turner’s research for his lectures as Professor of Perspective. However, these anecdotes no doubt enhanced Turner’s sense of belonging to a living academic and artistic tradition (including the learned Discourses of the Royal Academy’s founding President, Sir Joshua Reynolds), and there are also many passages concerning perspective, light, colour and proportion.

‘The First Booke: Of the Naturall and Artificiall Proportions of Things’, pp.1–[120]: folios 32 verso–34 verso (D07406–D07410); 38 recto (D07417); and probably part of 47 verso (D07436)

‘The Seconde Booke: Of the Actions, Gestures, Situation, Decorum, Motion, Spirit, and Grace of Pictures’, pp.1–92 of new page sequence: folios 38 verso–39 verso (D07418–D07420) – see also immediately below for the latter

‘The Fourth Booke: Of Light’, pp.135–77: folio 41 recto (D07423)

‘The Fifth Booke: Of the Perspectives’, pp.179–218: folios 41 verso–42 verso (D07424–D07426); 60 verso, including a diagram (D07457); 61 verso (D07459); 62 recto (D07460)

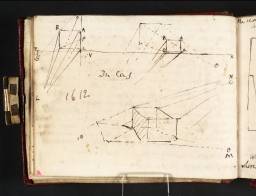

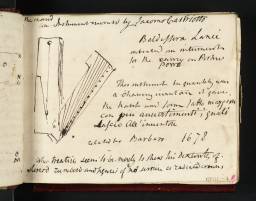

3. Notes and diagrams from other books and unidentified sources

Turner’s notes are taken from a wide range of works on perspective, geometry and art history; full bibliographical details are given in the individual catalogue entries. As Davies observes, he probably made use of copies at the British Museum, now held at the British Library, London, including two unique volumes of various treatises bound together.18 This appears to be confirmed by his having to refer to Viator’s treatise by its date and imprint rather than its title and author, as the British Museum’s copy lacked a title page (see entry for folio 27 recto; D07396).

Turner’s pages marked * comprise or include diagrams. Copies of perspective treatises by Androuet de Cerceau, Highmore, Kirby, Lamy, Lowry, Moxon, Priestley and Taylor were in the artist’s library at his death;19 that he did not make notes from these texts in the present sketchbook may suggest that he had acquired some if not all of them in preparation for his lectures, consulting them at leisure. Some notes from Priestley and Kirby are to be found in the Greenwich and Windmill and Lock sketchbooks respectively (Tate; Turner Bequest CII, CXIV).20

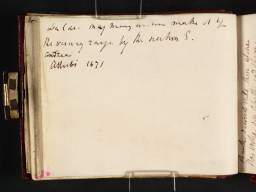

Aleaume and Migon 1643: folio 66 recto* (D07465)

Cousin 1560: folio 51 recto* (D07443)

after Dürer: folio 55 recto* (D07451)

Sirigatti 1625: folio 46 recto* (D07433)

Vitellio 1535: folio 1 verso (D07356)

Unidentified sources or Turner’s own comments: folios 12 verso (D07377); 28 verso (D07399); 35 recto–37 verso (D07411–D07416); 47 verso (D07436), probably in part from Lomazzo – see section 2 above; 50 recto (D07441); 62 verso (D07461); 63 recto (D07462); 71 recto* (D07471); 80 recto (D07488); 81 recto* (D07490)

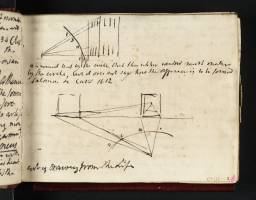

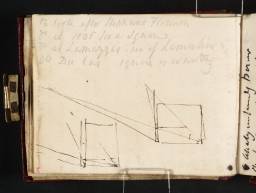

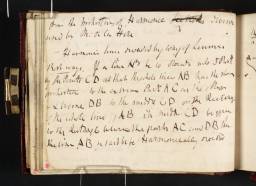

4. Draft lecture notes on light, shadow and reflections

John Gage has discussed the extensive sequence of notes towards the end of the sketchbook as an example of Turner’s close observation of natural phenomena,21 engaging with the question of sunlight travelling in parallel lines or otherwise in response to a chapter of The Art of Painting by Gérard de Lairesse (1640–1711),22 in the English translation by John Frederick Frisch (London 1738 and later editions). The phrasing suggests a spoken address, but as Gage notes, the arguments are rambling, and do not appear to have been incorporated into Turner’s perspective lecture texts. The pages marked * include ad hoc diagrams, visually augmenting the arguments. The text begins on folio 91 verso, running back to folio 82 verso:23

Further notes and diagrams relating to reflections and the casting of light and shadows from polished objects and water run back from folio 81 verso to folio 72 verso, again phrased in terms of a lecture (Turner’s fifth perspective lecture concerned reflection and refraction):

folios 72 verso (D07473); 73 verso (D07475); 74 verso (D07477); 75 verso (D07479); 76 verso (D07481); 77 verso (D07483); 78 verso (D07485); 79 verso (D07487); interspersed with four full-page diagrammatic drawings relating to these notes: 76 recto (D07480); 78 recto (D07484); 79 recto (D07486); 81 verso (D07491)

5. Poetry

Seventeen pages are devoted wholly or principally to Turner’s original verse:24

‘Must toiling Man for ever meet disgrace’: folios 20 recto–folio 26 recto (D07388–D07394)

‘The sweets of the Bee and the bloom of the Rose’: folio 28 recto (D07398)

6. Notes on the relationship between poetry and painting

Andrew Wilton has described Turner’s arguments as ‘tortuously expressed’ but with ‘interesting reflections on the essential differences between the tasks of painter and poet’ and ‘dynamism in the depiction of nature’.25 The sequence begins on folio 53 verso and should be read in reverse order of the folios:

Ziff 1984, pp.45, 46, 47, 48, 49 notes 6, 7 and 11, p.50; Davies 1994; see also selected references in Gage 1969.

Sarah Bakewell, ‘Haydock, Richard (1569/70–c.1642)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, accessed 5 March 2008, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/12746 .

Martin Kemp, ‘Lomazzo, Giovanni Paolo [Gianpaolo]’, Grove Art Online, accessed 5 March 2008, http://www.oxfordartonline.com .

See also Mansfield Kirby Talley, Portrait Painting in England: Studies in the Technical Literature before 1700, [London] 1981, pp.22–9; and Caroline van Eck (ed.), British Architectural Theory 1540–1750: An Anthology of Texts, Aldershot 2003, pp.21–2.

Davies 1994, p.75; for the two volumes mentioned see also John Gage in Martin Butlin, Andrew Wilton and Gage, Turner 1775–1851, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1974 , p.181 under no.B58.

Andrew Wilton, Turner in his Time, London 1987, pp.246–7; compare list in D[ugald] S. MacColl, ‘Notes on English Art II – Turner’s Lectures at the Academy’, Burlington Magazine, vol.12, March 1908, p.345 note 7.

Alain Roy, ‘Lairesse, Gérard de’, Grove Art Online, accessed 1 May 2008, http://www.oxfordartonline.com .

Technical notes

How to cite

Matthew Imms, ‘Perspective sketchbook c.1809’, sketchbook, June 2008, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www