Joseph Mallord William Turner Notes on Anatomy, Geometry and the Structure of the Eye, for Perspective Lectures (Inscriptions by Turner) c.1808-9

Joseph Mallord William Turner,

Notes on Anatomy, Geometry and the Structure of the Eye, for Perspective Lectures (Inscriptions by Turner)

c.1808-9

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Folio 29 Recto:

Notes on Anatomy, Geometry and the Structure of the Eye, for Perspective Lectures (Inscriptions by Turner) circa 1808–9

D06776

Turner Bequest CII 29

Turner Bequest CII 29

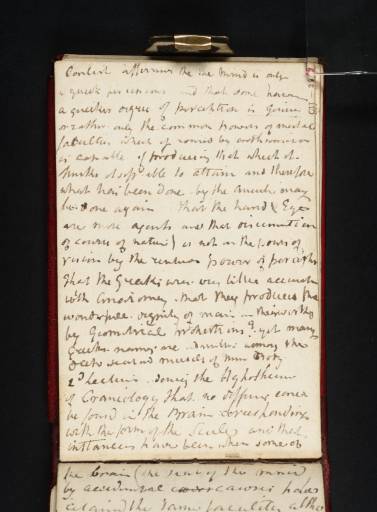

Inscribed by Turner in ink (see main catalogue entry) on white wove paper, 115 x 76 mm

Inscribed by John Ruskin in red ink ‘29’ top right, running vertically

Stamped in black ‘CII 29’ top right, running vertically

Inscribed by John Ruskin in red ink ‘29’ top right, running vertically

Stamped in black ‘CII 29’ top right, running vertically

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

References

1909

A.J. Finberg, A Complete Inventory of the Drawings of the Turner Bequest, London 1909, vol.I, p.268, CII 28a as ‘Notes on perspective’.

1969

John Gage, Colour in Turner: Poetry and Truth, London 1969, pp.110, 250 note 181.

1982

Barry Venning, ‘Turner’s Annotated Books: Opie’s ‘Lectures on Painting’ and Shee’s ‘Elements of Art’, Turner Studies, vol.2, no.1, Summer 1982, p.37.

1994

Maurice William Davies, ‘J.M.W. Turner’s Approach to Perspective in his Royal Academy Lectures of 1811’, unpublished Ph.D thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art, London 1994, p.287.

These notes (not transcribed by Finberg) continue on folio 28 verso (D06775); for convenience they are given in full here:

Carlisle affirms the mind is only | a quick perception and that some having | a quicker degree of perception is Genius | or rather only the common powers of mental | faculties which if carried by enthusiasm | is capable of producing that which it | thinks itself able to obtain and therefore | what has been done by the ancients may | be done again. That the hand & Eye | are mere agents and that discrimination | if cause of nature is not in the power of | vision by the ... power of perception | That the Greeks were very little acquainted | with Anatomy. That they produced the | wonderful dignity of man in their marbles | by Geometrical proportions. Yet many | greek names are admitted among the | ... muscles of the Body | 2nd lecture. denying the Hypotheses | of Craniology that no differences | be found in the Brain corresponding | with the form of the Skull and that | instances have been when some of [continued on folio 28 verso] the brain (the seat of the mind) | by accidental causes have | retained the same faculties although | some parts of the seat (supposed to belong to filial affection) ... I shall in future show the | eye is placed rather divergent | to the side of the Head and looking | thus [here Turner has added a sketch] therefore the transparent part of the [eye] appears to move yet | globe of the eye or is centrically | placed and by being rather out | of the parallel enables the trans | parent part to reflect objects from the side view

For Turner’s notes for his lectures as Professor of Perspective at the Royal Academy see Introduction to this sketchbook and under folio 15 (D06749). This additional text is probably connected with his plans for Lecture 1, on perspective and geometry, in which he sought to establish the relationship between his subject and the others taught by the Academy’s Professors, including anatomy and sculpture.1 It also seems to anticipate his discussion of the subject of vision, developed in his later courses of lectures from 1814 to 1818.

Rather than perspective alone, as Finberg surmised, these notes are concerned with broader issues which were being debated around 1808–9. As John Gage recognised, the observations on the structure of the eye, and on the mind as the seat of perception, are based on Anthony Carlisle’s lectures on anatomy;2 comments on the Greeks come from the same source. Carlisle, Surgeon to the Westminster Hospital since 1793, was appointed Professor of Anatomy at the Academy in 1808, despite his belief that too close a knowledge of the subject hindered artistic judgement.3 His appointment dismayed young artists like Benjamin Robert Haydon and David Wilkie who favoured Charles Bell, the Scottish anatomist who had given anatomical demonstrations and dissections for them in London in 1805–6. Turner and Carlisle became close friends, but Turner’s notes here imply some disagreement with his colleague, notably over the source of truth to nature in Greek sculpture and how this might be revived. Also in 1808, the Elgin Marbles were on display in London’s Park Lane, having recently been shipped from Athens. To Haydon in particular, it was apparent that the Greek sculptors must have achieved their anatomical knowledge by dissection. He went on to formulate his own teaching programme, offered to students in his own ‘school’ from 1815, giving primacy to dissection and life study as well as study from the Marbles and works of art like Raphael’s Tapestry Cartoons. This ran counter to the tuition at the Academy and it is significant that despite the reservations evident here, Turner’s first lecture, in the form in which he delivered it, emphasised geometrical proportion over anatomical study in picturing the human body.

Turner’s notes, as Venning observed, also refute the new fashion for Craniology. This dubious branch of psychology was developed by a Viennese doctor, Franz Joseph Gall, promoted by him on a lecture tour around Europe in 1805 and further described in a learned London journal the following year.4 According to Gall, particular faculties and personality traits were located in specific parts of the brain and, as he also believed that the shape of the skull corresponded to that of the brain, could be recognised by the contours of the cranium. Thus it was possible to identify genius, madness or other propensities from external appearance. Distinctly unconvinced, as these notes show, Turner also gave Craniology short shrift in a marginal note to his copy of John Opie’s Lectures on Painting (1809), alongside the author’s claim that the ancients ‘observed how the situation and shape of the head varied with the increase or decrease of intellectual vigour and comprehension’.5 Turner was a subscriber to this posthumous edition of Opie’s lectures as the Academy’s Professor of Painting, and read them in preparation for his own course on perspective.

David Blayney Brown

March 2007

For a discussion of this lecture see Maurice Davies, Turner as Professor: The Artist and Linear Perspective, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1992, pp.31–-6

Gage 1969, pp.110, 250 note 181. Turner’s notes refer to Carlisle’s first two lectures. For notes on a third lecture see Windmill and Lock sketchbook, folio 6 verso (Tate D07968; Turner Bequest CXIV 6a)

Carlisle’s views had been set out in an article in The Artist, 4 July 1807; for Carlisle and further discussion of these issues, see Martin Postle in Ilaria Bignamini and Martin Postle, The Artist’s Model: Its Role in British Art from Lely to Etty, exhibition catalogue, University Art Gallery, Nottingham 1991, p.23

How to cite

David Blayney Brown, ‘Notes on Anatomy, Geometry and the Structure of the Eye, for Perspective Lectures (Inscriptions by Turner) c.1808–9 by Joseph Mallord William Turner’, catalogue entry, March 2007, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www