Joseph Mallord William Turner Leeds from Beeston Hill 1816

Image 1 of 1

Sorry, no image is available of this artwork

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Folio 48 Verso:

Leeds from Beeston Hill 1816

D09883

Turner Bequest CXXXIV 79

Turner Bequest CXXXIV 79

Pencil on white wove paper with gilt edges, 179 x 254 mm

Inscribed by Turner in pencil ‘x’ several times along the horizon, and again near the centre, ‘[?T... G.]’ centre left, and ‘Pond’ bottom centre

Blind-stamped with Turner Bequest monogram bottom left

Stamped in black ‘CXXXIV – 79 – 80’ bottom right

Inscribed by Turner in pencil ‘x’ several times along the horizon, and again near the centre, ‘[?T... G.]’ centre left, and ‘Pond’ bottom centre

Blind-stamped with Turner Bequest monogram bottom left

Stamped in black ‘CXXXIV – 79 – 80’ bottom right

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Exhibition history

1904

National Gallery, London, various dates to at least 1904 (525 (a)).

References

1904

E.T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn eds., Library Edition: The Works of John Ruskin: Volume XIII: Turner: The Harbours of England; Catalogues and Notes, London 1904, pp.254 no.11, 633 no.525 (a), as ‘Sketch of the Town of Leeds’.

1909

A.J. Finberg, A Complete Inventory of the Drawings of the Turner Bequest, London 1909, vol.I, p.383, CXXXIV 79, as ‘Sketch of the town of Leeds’.

1974

Martin Butlin, Andrew Wilton and John Gage, Turner 1775–1851, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1974, p.82 under no.186, as CXXXIV ‘79v’.

1974

Gerald Wilkinson, The Sketches of Turner, R.A. 1802–20: Genius of the Romantic, London 1974, reproduced p.144.

1977

Christopher White, English Landscape 1630–1850: Drawings, Prints & Books from the Paul Mellon Collection, exhibition catalogue, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven 1977, p.77 and note 2 under no.136, as CXXXIV ‘79v’.

1977

Gerald Wilkinson, Turner Sketches 1789–1820, London 1977, reproduced p.134.

1979

Andrew Wilton, J.M.W. Turner: His Life and Work, Fribourg 1979, p.362 under no.544.

1982

Louis Hawes, Presences of Nature: British Landscape 1780–1830, exhibition catalogue, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven 1982, p.200 under no.VI.26.

1983

Francis W. Hawcroft, ‘The Most Beautiful Art of England’: An Exhibition of Fifty British Watercolours, c.1750–1850, to Celebrate the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Friends of the Whitworth, exhibition catalogue, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester 1983, p.[72] under no.31.

1984

David Hill, In Turner’s Footsteps: Through the Hills and Dales of Northern England, London 1984, p.104, as 1816.

1986

Stephen Daniels, ‘The Implications of Industry: Turner and Leeds’, Turner Studies, vol.6, no.1, Summer 1986, p.10, as probably 1816, p.11 ill.2.

1989

Ann Chumbley and Ian Warrell, Turner and the Human Figure: Studies of Contemporary Life, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1989, p.46 under no.43.

1991

Horst Koch, William Turner, Kirchdorf/Inn 1988, trans. Stephen Gorman, London 1991, reproduced p.78.

1997

William S. Rodner, J.M.W. Turner: Romantic Painter of the Industrial Revolution, Berkeley and London 1997, p.87, fig.36, as probably 1816.

1998

James Hamilton, Turner and the Scientists, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1998, pp.92, 140 no.79, fig.94.

2008

David Hill, Turner and Leeds: Image of Industry, Leeds 2008, pp.109, 114–36, ill.96 (colour), as 1816.

Turner’s earliest experience of the Leeds area came on his tour of the North of England in 1797; on that occasion he focused on the conventional subjects of Kirkstall Abbey, then in a rural setting three miles west of the town, and the Harewood House estate, about seven miles north.1 He visited Kirkstall again in 1808 and 1809 (see the Kirkstall and Kirkstall Lock sketchbooks; Tate; Turner Bequest CVII, CLV), but despite several extended visits to Walter Fawkes at Farnley Hall about ten miles to the north-west (see the sketchbook’s Introduction), he only turned his attention to the town itself in the present book.

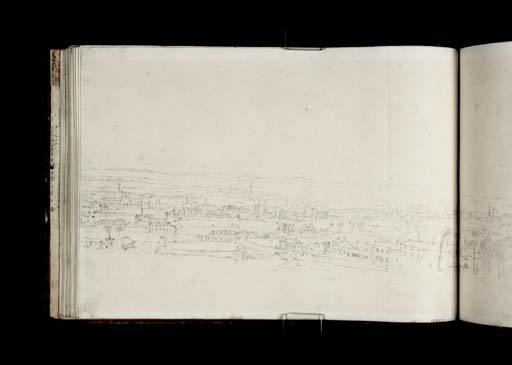

The viewpoint for this panoramic view north over the industrial town centre of Leeds (now a largely post-industrial West Yorkshire city) is ‘the shoulder of Beeston Hill’, and can be approximated today from the open ground on the west side of Beeston Road between Lodge Lane and Coupland Street.2 David Hill has described this as ‘one of the few viewpoints from which the whole extent of the city can be comprehended, stretching west along the river [Aire] towards Armley and Kirkstall and east towards Swillington and Castleford’;3 the 1806 Leeds Guide described this scene: ‘Perhaps the most pleasing view of Leeds’.4 It mentions the ‘elegant buildings’ and churches, but not the mills; businesses had doubled in twenty years, and the population had increased by 50 per cent to 75,000, driven by the demand for textiles during the Napoleonic Wars.5 The view, drawn with great concentration to the very left-hand edge of the present page, is then continued to the left on folio 47 verso (D09832; Turner Bequest CXXXIV 38), and immediately to the right on folio 49 recto opposite (D09884; Turner Bequest CXXXIV 80).

As has long been recognised,6 the drawing was faithfully followed in Turner’s 1816 watercolour Leeds (Yale Center for British Art, New Haven),7 as discussed below. Its intricate cityscape can be matched building for building with the sketch, although the road and figures are not indicated here, and were only roughly suggested in a separate, summary sketch on folio 47 recto (D09833; Turner Bequest CXXXIV 38a), and the range of buildings in the foreground becomes slightly truncated. The left-hand edge of the present drawing corresponds precisely with the limit of the view transcribed in the watercolour, in which the prospect extends further to the right, following about half of the limited continuation of the drawing on folio 49 recto. John Ruskin described the view as ‘one of the most minutely finished pencil outlines in the collection.’8 Compare also the rapid sketches from similar viewpoints on folios 81 verso and 82 recto (D09831, D09841; Turner Bequest CXXXIV 37a, 45a), including indications of figures which may have prompted ideas for some of those shown in the watercolour.

David Hill has dated the Leeds sketches in this book to ‘probably ... the beginning of September 1816’9 (see the Introduction). He has carefully identified most of the individual landmarks in the present ‘tour de force of placement and observation’10 and discussed their historical, architectural and social significance. They are briefly noted here from left to right, from west to east along the valley of the River Aire. The multi-storey buildings on the left are John Marshall’s flax manufactory,11 with the houses of Park Place on the far side of the River Aire behind it12 and beyond them the staged tower of St Paul’s Church, Park Square (demolished in 1905).13 Just to the right, from top to bottom, are the low, pedimented Leeds Infirmary,14 Fenton and Murray’s foundry,15 and Holbeck Moor Mill with its dark chimney.16 The nearer, two-storey building below and to the right of the mill is Holbeck Moor workhouse.17 Above it, in the distance to the right of Leeds Infirmary, is the long, level roof of the large Coloured Cloth Hall.18 Of the three chimneys to its right, the one on the left marks Armistead’s Oil and Mustard Factory, and that on the right Water Hall (flax) Mills.19

In the distance above the open land and trees by the river towards the centre of the page are the tower of St John’s Church and the prominent spire of Holy Trinity Church, Boar Lane.20 Just to the right of the spire on the far hillside is Gledhow Hall,21 marked with one of the ‘x’s above the skyline, and the subject of a number of closer studies in this sketchbook and an 1816 watercolour; see under folio 3 recto (D09805; Turner Bequest CXXXIV 15). The large block below and to the right of the spire is Benyon’s Flax Mill in Hunslet.22 To the right in turn, beyond some further chimneys, is the Wesleyan Chapel in Meadow Lane, a compact block with a shallow roof built between 1815 and 1816.23 In recording this tiny detail, Turner unwittingly gives an important clue to the date of his drawing. In shade below the chapel are the kilns of Hunslet Hall Pottery, and below them again the ‘pond’ noted by Turner, perhaps evidence of the extraction of clay.24

Of the remaining buildings in the distance, the tower of St Peter’s Parish Church25 stands to the left of the extensive Leeds Pottery, which is continued onto folio 49 recto opposite.26 Hill describes the houses ascending Beeston Hill in the foreground as ‘good’ and in a ‘desirable spot’, clear of the town’s smoke, carried north-east by the prevailing wind; the nearest has windows immediately under the eaves indicating weaving lofts from the pre-industrial period when weavers worked at home.27 In the foreground of the watercolour, Turner introduced various figures of cloth workers, children gathering mushrooms, masons, factory workers, a butcher and milk carriers, and Hill has observed that there was ‘now so much going on in the industrial foreground that the view of the town had become something of a background event’,28 describing the watercolour as ‘the first of its kind. The character of this landscape was a creation of very recent years’ and ‘only in Leeds had the industrial buildings proliferated in such great quantity in the immediate precincts of the town. In those terms Leeds was the first industrial city and Turner’s watercolour the first industrial cityscape.’29 While sometimes incorporating aspects of industrialisation in his work, Turner would next study such scenes in their own right at Birmingham, Coventry and Dudley on his Midlands tour of 1830 (see elsewhere in this catalogue).30

Despite its novel subject and the elaborate care Turner took over it, the watercolour’s immediate purpose and ownership are uncertain.31 Unusual in being fully signed and dated ‘JMW Turner RA 1816’, it has been proposed as a subject for Dr Thomas Dunham Whitaker’s Loidis and Elmete; or, an Attempt to Illustrate the Districts Described in those Words by Bede; and Supposed to Embrace the Lower Portions of Aredale and Wharfedale, Together with the Entire Vale of the Calder, in the County of York (Leeds and Wakefield 1816), which included four illustrations from Turner’s works, while a fifth, showing Gledhow Hall (which Turner drew elsewhere in this sketchbook as noted above) was announced in the text but only issued in 1820. David Hill has suggested that the Gledhow and general Leeds views were intended as a thematic pair.32 (For more on Whitaker, the Loidis subjects, and Turner’s extensive work for his other publications, not least elsewhere in Yorkshire in 1816, see the overall Introduction to the present grouping.)

A lithograph by the landscape painter James Duffield Harding (1798–1863) after Turner’s Leeds watercolour was published in 1823 (no Tate impression; British Museum, London, holds an impression), lettered as ‘from a Drawing in the possession of J. Allnut, Esq. London, Pub’d by Rodwell & Martin’,33 a firm known for ‘fine illustrated books’.34 In his two-volume catalogue of Turner’s prints, in 1908 W.G. Rawlinson initially described the lithograph as intended for ‘“Loidis and Elmete,” 2nd Edition, 1823’35 and stated that ‘a later edition of 1823 has in addition a large lithograph of the town of Leeds, also after [Turner].’36 However, when he came to catalogue the print in detail in 1913 he noted that it was said ‘to have been intended for an illustration to Whitaker’s “Leodis and Elmete.” I have, however, never seen it in a copy of that work’.37 Later writers have suggested that Turner intended the design for Whitaker’s book, but also that it was not included on the grounds of being unsuitable in an antiquarian context and Whitaker’s antipathy to industrial developments.38 Most recently, Jan Piggott has noted that the format of the lithograph would have been too large to go with Whitaker’s book.39 John Allnutt, a London wine merchant and patron of Turner’s since about 1804,40 was evidently the watercolour’s owner by in 1823, and Piggott has suggested that Allnutt took it upon himself to have the design lithographed and published independently, noting the case of his publishing an engraving after another of his Turners in 1827; the artist reportedly demanded an additional copyright payment, although he had no legal grounds as the law then stood, and the two fell out.41 Leeds was the only lithograph from one of Turner’s works to be published in his lifetime, and the apparent lack of ‘touched’ proofs with his annotations suggests a lack of direct involvement.42

For an overview, see David Hill, Turner in the North: A Tour through Derbyshire, Yorkshire, Durham, Northumberland, the Scottish Borders, the Lake District, Lancashire and Lincolnshire in the Year 1797, New Haven and London 1996, pp.22–9, 152–61.

See Hill 2008, p.103; for Hill’s photographs of the ever-changing view see p.3 (1992) and pl.95 (2006).

See Cook and Wedderburn 1904, pp.254, 633; see also Finberg 1909, I, p.383, Butlin, Wilton and Gage 1974, p.82, White 1977, p.77, Wilton 1979, p.362, Hawes 1982, p.200, Hawcroft 1983, p.[72], Daniels 1986, pp.10, 11, Chumbley and Warrell 1989, p.46.

Catalogue of the Sketches and Drawings by J.M.W. Turner, R.A. Exhibited in Marlborough House in the Year 1857–8 in Cook and Wedderburn 1904, p.254.

Ibid., p.109; discussions of the socio-economic aspects of the watercolour include Hill 1984, p.104, Daniels 1986, pp.10–17, Eric Shanes, Turner’s England 1810–38, London 1990, p.78, Rodner 1997, pp.87–94, Hamilton 1998, p.92, Gillian Forrester in John Baskett and others, Paul Mellon’s Legacy: A Passion for British Art, exhibition catalogue, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven 2007, pp.283–4 no.88, and Hill 2008, pp.135–52.

W[illiam] G[eorge] Rawlinson, The Engraved Work of J.M.W. Turner, R.A., vol.I, London 1908, p.cxiv, and vol.II, London 1913, pp.214, 407 no.833.

J.R. Piggott, ‘Turner among the Landscape Engravers: I: Chiaroscuro, Copper, Stone and Wood’, Turner Society News, No.121, Spring 2014, p.13.

Rawlinson I 1908, p.cxiv; see also Luke Herrmann, Turner Prints: The Engraved Work of J.M.W. Turner, Oxford 1990, p.76, but also p.274.

See White 1977, p.77, Hawes 1982, p.200, Daniels 1986, pp.10, 12, 17, Shanes 1990, p.78, Rodner 1997, p.94, Gillian Forrester in John Baskett and others, Paul Mellon’s Legacy: A Passion for British Art, exhibition catalogue, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven 2007, p.284 no.88, Hill 2008, pp.136–8.

Technical notes:

The recto of the leaf is blank, and unnumbered in Finberg’s 1909 Inventory; by his usual convention the present page should be ‘79a’, but the sketchbook’s leaves have since been bound in a different sequence (see the Introduction).

Except for strips round the edges, the page has darkened through prolonged exhibition, when it was mounted with the continuation on folio 49 recto opposite (D09884; Turner Bequest CXXXIV 80).

Matthew Imms

July 2014

How to cite

Matthew Imms, ‘Leeds from Beeston Hill 1816 by Joseph Mallord William Turner’, catalogue entry, July 2014, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, September 2014, https://www