Joseph Mallord William Turner Critical Notes by Turner on Works of Art in the Palazzo Corsini, Rome; and Notes by James Hakewill on Travelling in Italy 1819

Joseph Mallord William Turner,

Critical Notes by Turner on Works of Art in the Palazzo Corsini, Rome; and Notes by James Hakewill on Travelling in Italy

1819

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Folio 13 Recto:

Critical Notes by Turner on Works of Art in the Palazzo Corsini, Rome; and Notes by James Hakewill on Travelling in Italy 1819

D13881

Turner Bequest CLXXI 13

Turner Bequest CLXXI 13

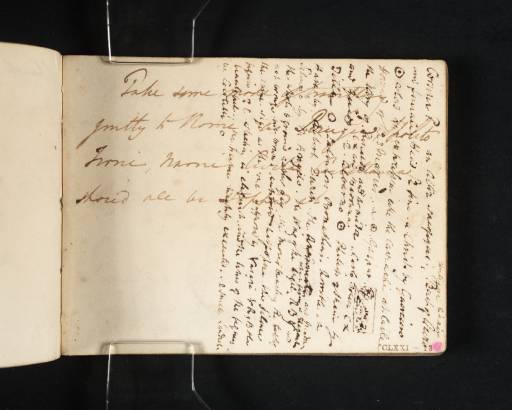

Black ink on white wove paper, 88 x 114 mm

Inscribed by the artist in black ink (see main catalogue entry)

Inscribed by James Hakewill in black ink (see main catalogue entry)

Inscribed by John Ruskin in red ink ‘13’ bottom right

Stamped in black ‘CLXXI 13’ bottom right

Inscribed by James Hakewill in black ink (see main catalogue entry)

Inscribed by John Ruskin in red ink ‘13’ bottom right

Stamped in black ‘CLXXI 13’ bottom right

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

References

1909

A.J. Finberg, A Complete Inventory of the Drawings of the Turner Bequest, London 1909, vol.I, p.496.

1925

Thomas Ashby, Turner’s Visions of Rome, London and New York 1925, p.9.

1968

Giovanni Carandente, ‘Un Viaggio di Turner in Umbria’, Spoletium: Rivista di arte, storia e cultura, 13, April 1968, p.16 note 7.

1969

John Gage, Colour in Turner: Poetry and Truth, London 1969, p.238 note 35.

1984

Cecilia Powell, ‘Turner on Classic Ground: His Visits to Central and Southern Italy and Related Paintings and Drawings’, unpublished Ph.D thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London 1984, pp.101, 151 note 1, 152 note 8, 153 notes 9–12, 404–5, 463 note 78, 469 note 138, 477 note 11, 479 note 36.

1987

Cecilia Powell, Turner in the South: Rome, Naples, Florence, New Haven and London 1987, pp.51, 65, 202 note 66, 203 notes 9 (under Chapter 4) and 4 (under Chapter 5).

1995

Cecilia Powell, Turner in Germany, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1995, p.11.

1997

James Hamilton, Turner: A Life, London 1997, p.199 note 17.

2008

James Hamilton, Nicola Moorby, Christopher Baker and others, Turner e l’Italia, exhibition catalogue, Palazzo dei Diamanti, Ferrara 2008, pp.38–9 and 89 note 35.

2009

James Hamilton, Nicola Moorby, Christopher Baker and others, Turner & Italy, exhibition catalogue, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh 2009, pp.34, 150 note 35.

Turner has used this page to make extensive critical notes on works of art in the Palazzo Corsini, Rome. This fifteenth-century palace, rebuilt in the eighteenth century, stands in the Trastevere district near the Villa Farnesina, at the foot of the Janiculum Hill. Today it houses the National Gallery of Ancient Art, a collection largely comprised of works amassed by the Corsini family. The artist’s comments were first fully transcribed by Cecilia Powell,1 and the inscription is repeated here with only minor variations from her text:

Corsini P. an Altar sarcofagus., ^Antique Chair^ Bust of Cicero | and female Head & fine. a Christ by Guercino | [dot encircled] colord [?His] expression like the Carrachi at Castle | Howard of the 3 Maries a .[+ encircled] Gaspar [sketch] | the story of Rinaldo and Armida. Carlo Dolci C X and | Guido, ^C X and Madonna^ 2. Albarno [dot encircled]. Philip of Spain by | Titian [circle] Salvators Prometheus horrible . a | Hare by Albert Durer the Annunciation and Madona | Silenzio by M. Angelo . the Wing of the Angel ^ which figure is Elegant^ R B Y and | the whole bground rather gry. the Moses breaking the tables | not bronze but brown. cup gold [...] the Silence | the same size as the one supposed by Vasari YR, B the | figure of C sleeping is elegant and the lines of the figures | beautiful. the [?figures] lightly executed. 2 small landscps | by Locotelli [circle]

Identifiable works which Turner respectively refers to are as follows:

a.

The Sedia Corsini, an antique chair or throne decorated with marble reliefs, a thumbnail sketch of which can be found in the Vatican Fragments sketchbook (Tate D15105; Turner Bequest CLXXX 1). The chair was the most important antiquity in the palazzo.2

b.

Ecce Homo by Guercino (1591–1666), the expression of which Turner compares to a painting by Annibale Carracci (1560–1609), The Dead Christ Mourned (‘The Three Maries’) circa 1604 (National Gallery), formerly in the collection of Lord Carlisle of Castle Howard.3 A small (crossed-out) study of the head of Christ can be seen in the Vatican Fragments sketchbook (Tate D15106; CLXXX 1a). Charlotte Eaton described it as ‘a painting which, notwithstanding the painful nature of the subject, and all its hackneyed representations, is full of such deep and powerful expression, is so elevated in its conception, and so faultless in its execution, that it awakens our highest admiration, and leaves an indelible impression on the mind.’4

c.

Rinaldo and Armida by Gaspard Dughet (known as Gaspar Poussin, 1615–75), which Eaton described as having ‘something of the witchery of the enchantress about it, for it charmed me so much, that I returned to the palace again and again to look at it.’5

d.

Carlo Dolci (1616–86) Christ

e.

Guido Reni (1575–1642) Christ and Madonna Albarno

f.

Philip of Spain by Titian (circa 1473/90–1576)

g.

Prometheus by Salvator Rosa (1615–73), the gruesome details of which Turner describes as ‘horrible’.

h.

A Hare by Hans Hoffman (circa 1530–91/2) formerly believed to be by Albrecht Dürer6

i.

The Annunciation and The Holy Family (or Madonna del Silenzio) which were then thought to be the work of Michelangelo, but were later attributed to Marcello Venusti (1512/15–79) working from the Renaissance master’s drawings.7

The Sedia Corsini, an antique chair or throne decorated with marble reliefs, a thumbnail sketch of which can be found in the Vatican Fragments sketchbook (Tate D15105; Turner Bequest CLXXX 1). The chair was the most important antiquity in the palazzo.2

b.

Ecce Homo by Guercino (1591–1666), the expression of which Turner compares to a painting by Annibale Carracci (1560–1609), The Dead Christ Mourned (‘The Three Maries’) circa 1604 (National Gallery), formerly in the collection of Lord Carlisle of Castle Howard.3 A small (crossed-out) study of the head of Christ can be seen in the Vatican Fragments sketchbook (Tate D15106; CLXXX 1a). Charlotte Eaton described it as ‘a painting which, notwithstanding the painful nature of the subject, and all its hackneyed representations, is full of such deep and powerful expression, is so elevated in its conception, and so faultless in its execution, that it awakens our highest admiration, and leaves an indelible impression on the mind.’4

c.

Rinaldo and Armida by Gaspard Dughet (known as Gaspar Poussin, 1615–75), which Eaton described as having ‘something of the witchery of the enchantress about it, for it charmed me so much, that I returned to the palace again and again to look at it.’5

d.

Carlo Dolci (1616–86) Christ

e.

Guido Reni (1575–1642) Christ and Madonna Albarno

f.

Philip of Spain by Titian (circa 1473/90–1576)

g.

Prometheus by Salvator Rosa (1615–73), the gruesome details of which Turner describes as ‘horrible’.

h.

A Hare by Hans Hoffman (circa 1530–91/2) formerly believed to be by Albrecht Dürer6

i.

The Annunciation and The Holy Family (or Madonna del Silenzio) which were then thought to be the work of Michelangelo, but were later attributed to Marcello Venusti (1512/15–79) working from the Renaissance master’s drawings.7

As Powell has discussed, Turner categorised some of these works using a three-tiered shorthand system: a blank circle; a dot in a circle; and a cross in a circle, the respective values of which are still unknown.8 Further notes and sketches relating to the Palazzo Corsini can be found in the Vatican Fragments sketchbook (Tate D15105–D15106; Turner Bequest CLXXX 1–1a). John Gage has described Turner’s colour analysis as indicative of his interest in the prismatic principle of colour harmony in Old Master paintings.9

The page also contains an inscription by James Hakewill (1778–1843), part of his advice to Turner on travelling in Italy in preparation for the artist’s first tour of the country in 1819 (see the introduction to the sketchbook). The text, first transcribed by Finberg,10 reads ‘Take some mode of travelling | gently to Rome, as Perugia, Spoleto | Terni, Narni, Civita Castellana | should all be stopped at.’ Turner visited all of these places during his 1819 tour, although Perugia formed part of his return journey from Rome, rather than the outward route via Florence recommended by Hakewill. Related sketches can be found in the Ancona to Rome sketchbook (Tate; Turner Bequest CLXXVII) and the Rome and Florence sketchbook (Tate; Turner Bequest CXCI). Hakewill’s notes continue on folio 13 verso (D13882).

Nicola Moorby

March 2010

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Critical Notes by Turner on Works of Art in the Palazzo Corsini, Rome; and Notes by James Hakewill on Travelling in Italy 1819 by Joseph Mallord William Turner’, catalogue entry, March 2010, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www