From the entry

Turner’s fourth visit to Scotland took place in August 1822, and coincided with the royal visit of King George IV. Subjects recorded in the two sketchbooks and associated sheets listed above, as well as resulting watercolours, engravings, oils and pencil composition studies, indicate that he made the journey in connection to two projects: the creation of vignette illustrations of the event for the ongoing Provincial Antiquities and Picturesque Scenery of Scotland publishing project, and for a proposed cycle of paintings commemorating the event. Travelling by sea, Turner also had the opportunity to sketch some of the subjects that he would later be commissioned to paint for the Ports of England engraving project, and to collect new views for unforeseen ventures. The King’s visit was strongly encouraged by Sir Walter Scott who was charged with devising a series of ceremonial events in which the King could take part. Guests and spectators were advised what to wear and how to behave by Scott’s ...

D34940–D34946

Turner Bequest CCCXLIV d 440–446

Turner Bequest CCCXLIV d 440–446

D13748

Turner Bequest CLXVIII A

Turner Bequest CLXVIII A

D13749

Turner Bequest CLXVIII B

Turner Bequest CLXVIII B

D17767

Turner Bequest CCIII J

Turner Bequest CCIII J

Turner’s fourth visit to Scotland took place in August 1822, and coincided with the royal visit of King George IV. Subjects recorded in the two sketchbooks and associated sheets listed above, as well as resulting watercolours, engravings, oils and pencil composition studies, indicate that he made the journey in connection to two projects: the creation of vignette illustrations of the event for the ongoing Provincial Antiquities and Picturesque Scenery of Scotland publishing project, and for a proposed cycle of paintings commemorating the event. Travelling by sea, Turner also had the opportunity to sketch some of the subjects that he would later be commissioned to paint for the Ports of England engraving project, and to collect new views for unforeseen ventures.1

The King’s visit was strongly encouraged by Sir Walter Scott who was charged with devising a series of ceremonial events in which the King could take part. Guests and spectators were advised what to wear and how to behave by Scott’s anonymously published booklet HINTS addressed to the inhabitants of Edinburgh and others in prospect of HIS MAJESTY’S VISIT by an old citizen. It is likely to have been Scott who encouraged Turner to come to Edinburgh, and to design two vignettes as frontispiece engravings to the 1826 two-volume edition of the Provincial Antiquities.

As early as 1819 Scott had proposed to Edward Blore, the project’s supervisor, that ‘either wood tail pieces or vignettes’ be added to the publication, suggesting that it ‘would add real value to the work’.2 The royal visit was a good subject for these additional illustrations, promoting not only the work by giving it contemporary relevance, but also Scott’s vision of Scottish national identity. Central to this vision were the Regalia of Scotland (the crown, sword and sceptre of state), of which Scott had initiated the rediscovery, and written about in the Provincial Antiquities. The Regalia formed the focal point of several ceremonies during the visit, and Turner’s vignette to volume one of the 1826 edition shows the procession with the Regalia on 22 August (Tate D13748; Turner Bequest CLXVIII A). His vignette to volume two also promoted Scott’s role in the royal visit, showing the poet greeting the King as he arrived in Leith Roads (Tate D13749; Turner Bequest CLXVIII B).

Turner may also have had his own project in mind. Two pages at the back of the King at Edinburgh sketchbook contain a series of nineteen composition studies, identified by Gerald Finley as depicting events from the royal visit in roughly chronological order (Tate D40979, D40980; Turner Bequest CCI 43a, inside back cover); (these will be referred to as compositions 1–[19]). These, Finley argues, form a proposal for a ‘Royal Progress’ series of paintings commemorating the tour.3 Highly flattering to the new King, it was probably envisaged as an attempt by Turner to gain his first royal commission, and as an impressive bid for royal favour. However, the series remained incomplete; only four paintings in various stages of finish have been identified as belonging to it.4

The dates of Turner’s tour coincided with George IV’s visit. He was certainly in Scotland by 14 August as he drew the arrival of the royal squadron that day, though the earliest reported sighting of the artist was on 7 August, when he was apparently spotted in the company of Sir Walter Scott, John Gilbert Lockhart, David Wilkie, William Collins and others outside Oman’s Hotel in Waterloo Place.5 This is spurious, however, as Gerald Finley has pointed out that Collins apparently had no notion of Turner being in Scotland until he saw him on the 15 August, and he and Wilkie did not arrive in the country themselves until the 9th or 10th.6 It is likely that Turner did arrive a day or so before the 14th as he was out on the water by about two o’clock that day, and may have attended a meeting of the shareholders of the Provincial Antiquities project in Edinburgh before then.7 The fact that he did not sketch the removal of the Regalia from Edinburgh Castle on 12 August suggests that he may not have been in Scotland on that day. A sketch of Hopetoun House suggests that Turner attended the knighting of Henry Raeburn on 29 August (Tate D17582; Turner Bequest CC 45a), the last day of the royal visit, and he probably left Scotland shortly after this.

The announcement of George IV’s historic visit to Scotland caught the attention of many artists besides Turner. Many were Scottish – James Skene, John Christian Schetky, William Home Lizars, Revd John Thompson of Duddingston, Alexander Nasmyth, Andrew Geddes, Hugh William Williams, G.P. Reinagle, Alexander Carse and William Allen – but others came from London and elsewhere: David Wilkie, William Collins, William Turner of Oxford, Denis Dighton, and Thomas Allom. The visit was regarded as a perfect subject for modern history painting (an increasingly popular genre) that would be popular to buyers, including, perhaps, the King himself.

The little that is recorded about Turner’s time in Edinburgh demonstrates that he spent some of it with his artist colleagues. In fact it may have been in discussion with his peers that he first developed his idea for a ‘Royal Progress’. The King’s Visit to Scotland sketchbook, used in Edinburgh, shows no indication of such a plan, which was first developed in the King at Edinburgh sketchbook, evidently used on his return to London (see the King at Edinburgh sketchbook Introduction).

Turner is reported to have been with William Collins and David Wilkie on several occasions: a dinner following the Provost’s Banquet,8 St Giles’s Cathedral on the 25th, and Hopetoun House on 29 August. Collins also saw Turner at Leith on the 15th, and the artists no doubt had many other opportunities to meet during the ceremonies. Discussions between the three artists probably influence Turner’s ideas. For example, in a letter to his mother, Collins wrote that he ‘could paint a series of pictures – but not one will I do (further than making sketches when I return) without commissions’.9 Although he was apparently ‘vastly secret and mysterious upon what I mean to paint’,10 so perhaps never made his plan explicit to Turner, the letter demonstrates that ideas of the sort were in the air; it is possible that Collins was as influenced by Turner’s ideas as Turner was by his.

Wilkie was perhaps the direct inspiration for one of Turner’s paintings. He was with Turner at the service at St Giles’s and is known to have been planning a work based on the event, though he was apparently disappointed when the moment he hoped to depict, George IV placing a donation in the Poors Plate, did not take place.11 Turner’s George IV at St Giles, Edinburgh; circa 1822 (Tate N02858),12 emulates Wilkie’s style, and, considering his contact with him at the event, he was presumably at the forefront of Turner’s mind when he made the work which could be seen as a direct challenge to the Scottish artist on his home turf.13

James Skene was a useful contact. As a member of Scott’s organising committee he had an insider’s knowledge of the arrangements of the royal visit, and Finley suggests that he may have helped Turner with his arrangements during the visit, perhaps also relaying Scott’s ideas and advice regarding the illustration of the ceremonies for the Provincial Antiquities. As a close associate of David Brewster, he may also have told Turner about the scientist’s recent work on optics. The desire to make contact with Brewster was apparently one motivation for Turner’s visit to Scotland, though he did not succeed in meeting him this time.14

Equally, the English architect, Charles Robert Cockerell seems to have been a useful contact for Turner. As a guest at the foundation stone ceremony, it may have been him that secured Turner access to the top of Nelson’s Monument from which he drew the event.15 He also, through Lord Elgin, secured Turner’s invitation to the Provost’s Banquet, and the two dined together twice in the company of various artists.16

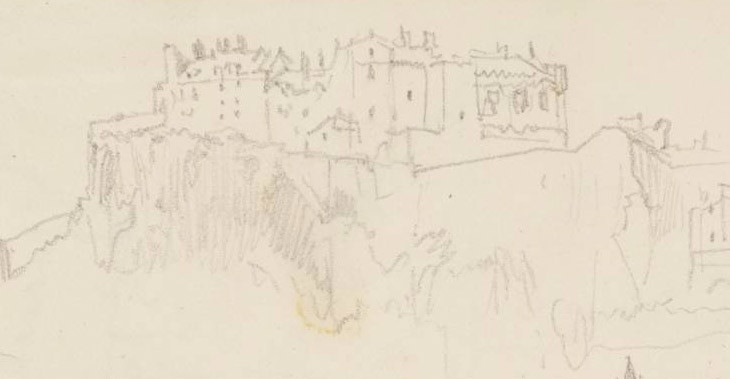

Henry Raeburn invited Turner to the dinner he hosted on 22 August, 17 and it was because of him that Turner may have been present at his knighting at Hoptoune House on the 29th. Turner’s contacts may also have helped him to gain entry to the Peers’ Ball, secure a ticket from the City Cess Office to attend the service at St Giles’s,18 gain permission from the Bailes of Leith to be allowed to stand on the Custom House Quay during the King’s landing,19 and to enter the Royal Palace and Half Moon Battery of Edinburgh Castle for an advantageous view of the Procession with the Regalia.

Turner’s journey to Edinburgh brought him from Greenwich to Leith along the east coast of Britain preceding King George who also travelled by sea. On his journey to and from Scotland Turner sketched Orford, Aldeburgh, Southwold, Lowestoft, Great Yarmouth, Spurn Head, Flamborough, Scarborough, Robin Hood’s Bay, Whitby, Redcar, Dunstanburgh Castle, Bamburgh Castle, the Farne Islands, Holy Island, Fast Castle, St Abb’s Head, Dunbar, Tantallon Castle, Bass Rock, North Berwick, Dirleton Castle and Leith.

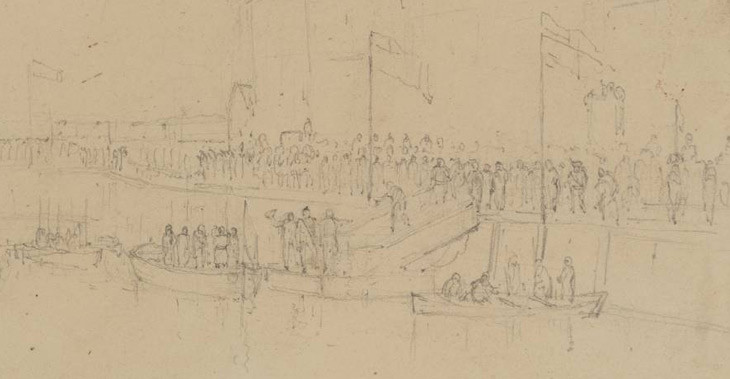

The rest of Turner’s sketches in the King’s Visit to Edinburgh sketchbook, and the studies in the King at Edinburgh sketchbook, are of, or closely related to, the events of the royal visit. The artist was out on the water shortly after the arrival of the royal squadron in Leith Roads on 14 August as there are sketches showing one of the boats still in the process of lowering its sails (Tate D17642; Turner Bequest CC 77). On this outing Turner witnessed from a distance the visit of Sir Walter Scott to the King’s yacht (Tate D17590; Turner Bequest CC 49a). This is reproduced in composition ‘1’ which formed the basis for Turner’s unfinished painting, The Mission of Sir Walter Scott, circa 1823 (Tate N02879).20 Turner returned to the water the following day to see the King’s departure by barge from the Royal George. This is represented in composition ‘2’ which was realised as the unfinished, The King’s Departure from the ‘Royal George’ in the Royal Barge, circa 1823 (Tate N02880).21 He also managed to get back to the shore in time to sketch the king’s landing at Leith (Tate D17608; Turner Bequest CC 58a).

Although he did not record the procession into Edinburgh, Turner did draw the empty route with the triumphal arch where the king received the keys to the city (Tate D17571–D17572; Turner Bequest CC 39a–40), and included the subject in his royal progress plan (composition ‘4’). Instead he may have rushed to stand on Arthur’s Seat to see the cavalcade arrive at Holyrood Palace (Tate D17573–D17574; Turner Bequest CC 40a–41; and composition ‘5’). Finley has suggested that Turner may have sketched the Reception of the Keys at Holyrood Palace (composition ‘6’) and the Regalia ceremony that day at Holyrood (Tate D17564; Turner Bequest CC 36; and Tate D40980; composition ‘7’),22 but subsequent research suggests that the setting does not resemble the throne room of the palace, although it is possible that he drew it from his imagination.

Turner did not sketch the Levee at Holyrood Palace on 17 August, although Finley suggests that composition ‘8’ may depict it. The setting does not match Holyrood, however, suggesting it has either been misidentified, or was drawn from the artist’s imagination. There are no sketches of the Court and Closet Audiences at Holyrood on 19 August, or the Drawing-room (reception for the ladies of Edinburgh) there on the 20th.

The procession from Holyrood to Edinburgh Castle with the Regalia on 22 August was the grandest public ceremony of the visit and seems to have held a particular interest to Turner. He drew the arrival of the procession (Tate D17565; Turner Bequest CC 36a), and sketched the king’s carriage (Tate D17563; Turner Bequest CC 35a). He chose another viewpoint, however, for composition ‘11’ and as the frontispiece to volume one of the Provincial Antiquities; this may have been based on a watercolour by James Skene, King George IV at Edinburgh Castle, circa 1822 (Edinburgh City Libraries).

The military review at Portobello Sands on 23 August is represented in the cycle (‘9’) by the word ‘Review’, but there are no sketches of the occasion. Turner was either not present, or found the challenge of depicting the event impossible to represent on paper as was the case in his composition plan. Finley has regarded a view of Edinburgh from Arthur’s Seat as representing the procession to or from the Review (Tate D17573–D17574; Turner Bequest CC 40a–41); but alternative subjects have since been proposed.

On the evening of the 22nd, George IV attended the Peers’ Ball (or Highland Ball) at the Assembly Rooms in George Street. Turner seems to have attended the event where he took particular interest in the highland costume (Tate D17580–D17581; Turner Bequest CC 44a–45), although he only drew the supper room, and not the ballrooms (Tate D17585; Turner Bequest CC 47).

There are apparently no sketches of the return of the Regalia to the crown room of the castle on the 24 August, although Finley has regarded three of the composition studies (‘12’, ‘13’, ‘14’) as relating to it. The king was not involved in this event, though he did that day attend the banquet at Parliament House given by the Lord Provost. Turner was also present and made sketches of the King’s table and various figures in attendance on seven small cards, presumably finding this method more convenient and discreet than using his sketchbook: Tate D34940–D34946 (Turner Bequest CCCXLIV d 440–446). The banquet was added, out of sequence, at the end of the royal progress plan ([19]) and was the subject of the unfinished oil painting, George IV at the Provost’s Banquet, circa 1822 (Tate N02858).23

As mentioned above, Turner was at the service at St Giles’s on 25 August, and although he could not sketch the service, he did draw the interior of the Cathedral on which he based composition ‘15’ and his painting, George IV at St Giles’s, Edinburgh: Tate D17559 (Turner Bequest CC 33a).

Turner seems not to have attended the Caledonian Hunt Ball on 26 August, but on the 27th he made sketches during the ceremony of the laying of the foundation stone of the National Monument on Calton Hill (see Tate D17540; Turner Bequest CC 22a). The ceremony is represented in the cycle as composition ‘17’, with ‘16’ showing the procession to Calton Hill that preceded it. This became the basis of Turner’s watercolour The March of the Highlanders, circa 1836 (Tate N04953), prepared for Fisher’s Illustrations to the Waverely Novels of Sir Walter Scott. That evening George IV attended a royal command performance of Rob Roy at the Theatre Royal.

The final numbered composition in the cycle (‘18’), a view of Holyrood, may represent the King’s departure from the palace on the 29 August. Turner did not draw the departure of the King at Port Edgar that afternoon, but probably attended his final official duty, the knighting of the artist Henry Raeburn and Captain Adam Ferguson at Hopetoun House (Tate D17582; Turner Bequest CC 45a).

The ‘Royal Progress’ proposal, as it exists in the King at Edinburgh sketchbook, is unformulated, uneven, and unfinished. There were mistakes in Turner’s chronology: the Review should appear after the Regalia Procession and the Banquet was apparently forgotten and placed unnumbered at the end of the sequence. There is an unequal distribution of subjects, with the return of the Regalia apparently taking three compositions; and there are likely to be either missing subjects, or too many, as 19 is an odd number for a cycle of paintings. Despite this, four of the compositions yielded oil paintings (albeit unfinished), and two formed the basis of engraved designs.

Gerald Finley and John Gage have also suggested that Turner pursued the possibility of having the Royal Progress series engraved; the prospect of publishing, however, had fallen through by the end of 1823.24 By this time Turner was engaged in his first royal commission to paint a large canvas of The Battle of Trafalgar, 21 October 1805, 1823–4 (National Maritime Museum, London),25 a project that would supplant his interest in the ‘Royal Progress’ project.

Ultimately, despite making a start on his ‘Royal Progress’ series, Turner discarded the project with only one oil near completion and his plans for a series of engravings abandoned. The composition studies, however, indicate that the two-week visit to Scotland in 1822 made a big impression on the artist. The visit resulted in four paintings, two vignettes and the illustration for Fisher; three of these were connected to Sir Walter Scott. While the trip did not result in the royal commission that Turner had perhaps hoped for, it strengthened his association with Sir Walter Scott: an association that led to further commissions for illustrations to books by or about Scott and to two further trips to Scotland in 1831 and 1834.

One of these ventures was the abandoned Picturesque Views on the East Coast of England, which included subjects that Turner had sketched during this sea journey. Turner’s sketches of Scarborough and Whitby came in useful when he was commissioned to make designs for the Ports of England project: Scarborough, circa 1825 (watercolour, Tate D18142; Turner Bequest CCVIII I); and Whitby, circa 1824 (watercolour, Tate D18143; Turner Bequest CCVIII J); Andrew Wilton, J.M.W. Turner: His Life and Work, Fribourg 1979, p.387 nos.751 and 752.

Gerald Finley, Turner and George the Fourth in Edinburgh 1822, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1981.

Gerald Finley originally regarded these as modelli, but modified his opinion in a later work to treat where he regarded them as unfinished oils: Finley 1980, p.249 note 29.

William Collins to his mother; William Collins, Memoirs of the Life of Williams Collins, Esq., RA With Selections from his Journals and Correspondence, 2 volumes, London 1848, Vol.I, pp.205–6, quoted in Finley 1975, p.31 note 13.

John Prebble 1988, p.323. See also Tate D17559 (Turner Bequest CC 33a) for more information about the event.

Martin Butlin and Evelyn Joll, The Paintings of J.M.W. Turner, revised ed., New Haven and London 1984, p.153 no.247.

Turner had made a similar challenge in 1807 when he exhibited A Country Blacksmith Disputing Upon the Price of Iron, and the Price Charged to the Butcher for Shoeing his Poney (Tate N00478; see Butlin and Joll 1984, pp.52–3 no.68) at the Royal Academy alongside Wilkie’s The Blind Fiddler, 1806 (Tate N00099). At the Academy exhibition of 1822 – just a few weeks before they both set out for Scotland – Wilkie’s Chelsea Pensions Reading the Waterloo Dispatch (oil, Apsley House, London) had received accolades, while Turner’s What You Will (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstone, Massachusetts) was regarded by critics as ‘something of an aberration’; (Butlin and Joll 1984, pp. 138–9 no.229). Although usually regarded as mimicking the style of Watteau, this painting also somewhat recalls Wilkie’s The Nursey Family in a Park’, circa 1816 (Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery Collection, Glasgow) and a similar work called, A Picnic, circa 1822 (oil, Tate N02131).

Turner’s relationship to Brewster is discussed in Gerald Finley, ‘Turner’s Colour and Optics: “A New Route” in 1822’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, vol.306 1973, pp.385–90.

Finley 1981, pp.21–22. It is interesting to note that David Wilkie and William Collins, who travelled to Scotland together in August 1822, also had a contact to help them gain entry to the ceremonies. This was Lord Liverpool, who provided them with a letter of recommendation as a form of accreditation, giving them semi-official status during the royal visit. See Prebble 1988, p.196.

Robert Mudie, An Historical Account of His Majesty’s Visit to Scotland, Edinburgh 1822, pp.209–213; John Prebble, The King’s Jaunt: George IV in Scotland, August 1822 ‘One and twenty daft days’, Edinburgh 1988, p.187

How to cite

Thomas Ardill, ‘George IV’s Visit to Edinburgh 1822’, November 2008, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www