Henry Moore OM, CH Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown

Image 1 of 13

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer

1964, cast date unknown

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

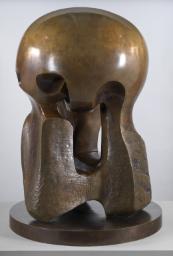

Comprising irregular abstract shapes with smooth, polished surfaces, Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer is exemplary of Moore’s work of the later 1960s. It was designed as the working model for a much larger public sculpture, installed in Toronto in 1966, and demonstrates Moore’s interest in creating compositions that convey a sense of balance with dynamic tension.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer

1964, cast date unknown

Bronze

776 x 788 x 652 mm

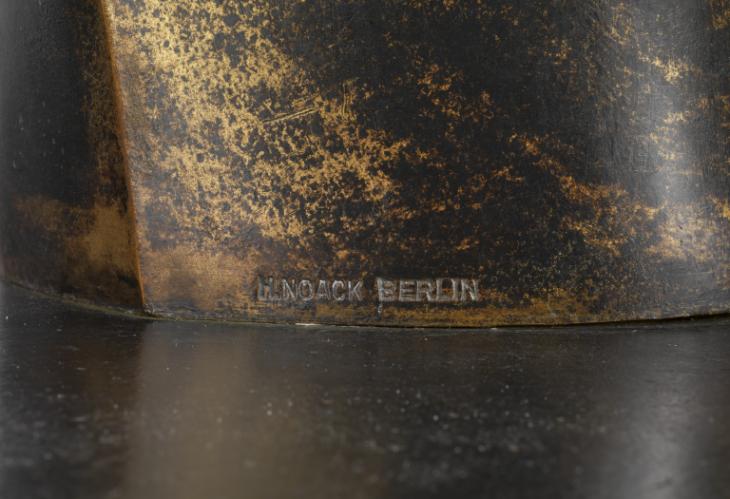

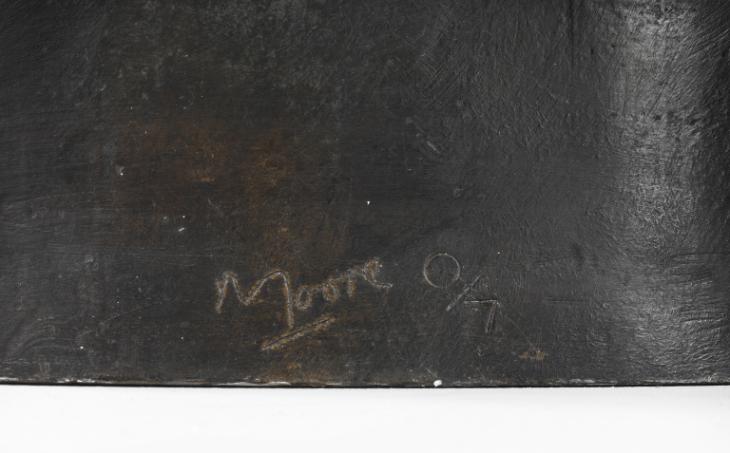

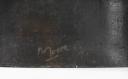

Inscribed ‘Moore 0/7’ on side of base and stamped ‘H.NOACK BERLIN’ on foot of sculpture

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s cast aside from edition of 7

T02299

Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer

1964, cast date unknown

Bronze

776 x 788 x 652 mm

Inscribed ‘Moore 0/7’ on side of base and stamped ‘H.NOACK BERLIN’ on foot of sculpture

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s cast aside from edition of 7

T02299

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1966

Henry Moore, British Council touring exhibition: Salla Dalles, Bucharest, February–March 1966; Slovak National Gallery, Bratislava, April–May 1966; National Gallery, Prague, June 1966; Israel Museum, Jerusalem, September–October 1966; Tel-Aviv Museum, Tel-Aviv, November–December 1966, no.32.

1969

Henry Moore Exhibition in Japan, 1969, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, August–October 1969, no.59.

1972

Mostra di Henry Moore, Forte di Belvedere, Florence, May–September 1972, no.133.

1975

Henry Moore: Fem Decennier, Skulptur, Teckning, Grafik 1923–1975, British Council touring exhibition: Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter, Oslo, June–July 1975; Kulturhuset, Stockholm, August–October 1975; Nordjyllands Kunstmuseum, Aalborg, October–November 1975, no.72.

1976

The Work of the British Sculptor Henry Moore, Zürcher Forum, Zürich, June–August 1976, no.80.

1978

Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, Cartwright Hall, Bradford, April–June 1978, no.39.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

2006–7

The Challenge of Architecture, The Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green, April–September 2006; Kunsthal, Rotterdam, October 2006–January 2007, no.109.

References

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, p.235 (plaster reproduced pls.223–6; ?another cast reproduced pl.227).

1967

Albert Elsen, ‘The New Freedom of Henry Moore’, Art International, vol.11, no.7, September 1967, pp.42–5 (Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1965–6 reproduced p.43).

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.204–9.

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968 (Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1965–6 reproduced pp.488–91).

1977

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 4: Complete Sculpture 1964–73, London 1977, no.534 (?another cast reproduced p.42).

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.57.

1979

Alan G. Wilkinson, The Moore Collection in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

1979

1979, pp.190–3 (plaster reproduced pl.170).

1981

The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, p.139, reproduced p.139.

2006

The Challenge of Architecture, exhibition catalogue, The Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green 2006, reproduced p.30.

2007

Jeremy Lewison, Henry Moore 1898–1986, Cologne 2007 (Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1965–6 reproduced p.76).

Technique and condition

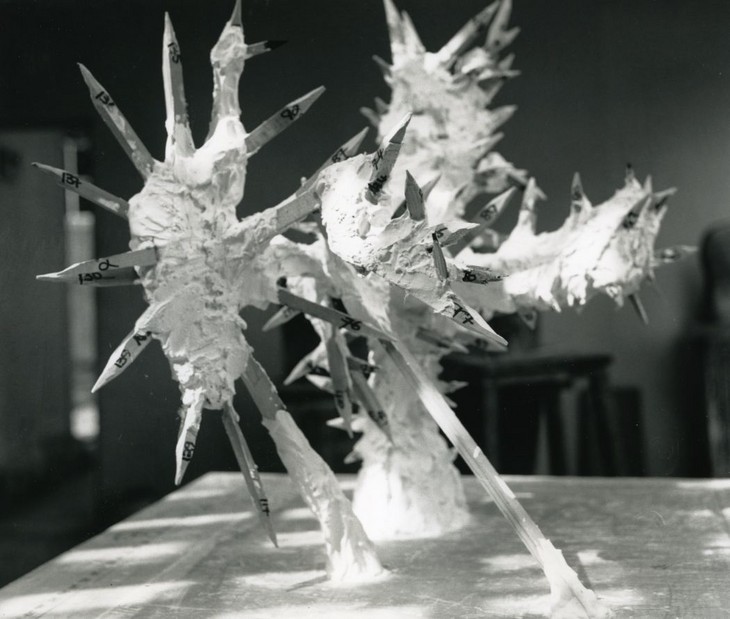

This sculpture was cast in bronze from an original model made of plaster. Moore would have made this model by building successive layers of wet plaster over a supportive armature constructed from lengths of wood wrapped in scrim, a bandage-like fabric (fig.1). After the plaster had been built up to the required depth and left to harden Moore used various files and abrasive papers to smooth the surface. The finished plaster model was then sent to a foundry where a mould was made from which the sculpture was cast in bronze.

After it was cast the surface of the bronze was finished with fine abrasives to give it a smooth, reflective surface that left little evidence as to how it was made. In contrast, the bronze base has a granular surface, which suggests that it was created using the sand casting technique. A large square patch of bronze can be seen around halfway up the curved edge of the D-shaped vertical form, and was probably inserted to repair a flaw in the cast (fig.2).

Armature for Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer with scrim and plaster 1964

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Armature for Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer with scrim and plaster 1964

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of square welding seam Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of square welding seam Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Following the completion of the casting and finishing process the sculpture was artificially patinated by applying chemical solutions to its surface, which reacted with the bronze to produce coloured compounds. The sculpture has a variegated brown patina that was probably achieved by using at least two different chemical recipes in varying concentrations. In certain areas the patina is transparent, which allows the lighter original colour of the raw bronze to shine through (fig.3). After patination the surface of the sculpture was lacquered to prevent the bronze from oxidising and changing colour. However, the lacquer has broken down in certain areas, which has speckled the patina and allowed the colour of the bronze to become duller over time (fig.4). A slight green haze can also be seen on one part of the sculpture. This may not have been induced artificially but may have been caused by chemicals in the air when the sculpture was displayed outdoors. In contrast to the sculpture’s variegated patina, the bronze base is a uniform dark brown.

Detail of patina on Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.2

Detail of patina on Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Detail of speckled patina on Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of speckled patina on Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

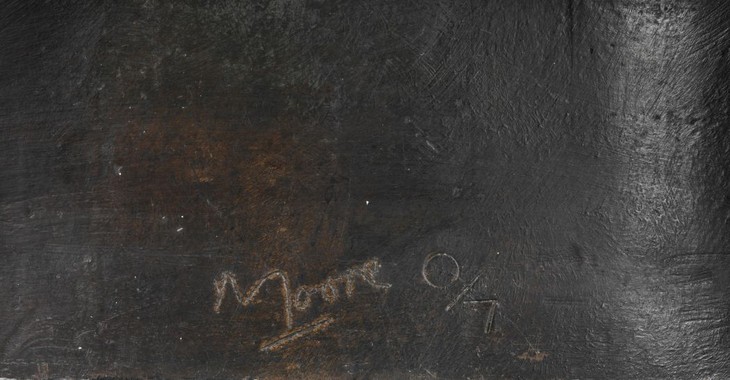

The stamped foundry mark ‘H.NOACK BERLIN’ can be seen on the vertical column near where it meets the base (fig.5), while the artist’s signature and edition number, ‘Moore 0/7’, are inscribed on the side of the base (fig.6).

Detail of foundry stamp on Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Detail of foundry stamp on Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2013

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2013, in Alice Correia, ‘Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, September 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964 is a bronze sculpture with smooth reflective surfaces comprising irregular rounded forms, sharp edges and points arranged into a seemingly organic, albeit abstract composition.

The sculpture is made up of two upright elements of roughly the same height – an elliptical, crooked column and a D-shaped wedge – connected in the middle by a curvaceous horizontal bridge that creates an arched space beneath (fig.1). The top of the column-like form is flat and smooth and appears truncated, while the bottom of the wedge-shaped form, which terminates in a sharp point, does not quite meet the base (fig.2).

Henry Moore

Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of gap between base and point of Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of gap between base and point of Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Two cantilevered protrusions project from one side of the horizontal bridge at right angles to the other elements of the sculpture. One has a rounded elliptical face and emerges smoothly from the joint between the wedge and the bridge, while the other, which has a flat, circular face, extends out from a swelling close to the midway point of the crocked column (fig.3).

From the side it is clear that the wedge is tilted at a slight angle so that it is not entirely vertical (fig.4). Indeed, the asymmetrical composition of the sculpture, whereby different elements project and twist in different directions, imbues it with a sense of dynamic tension, counterbalanced by the structure and solidity provided by the combination of equally weighted vertical and horizontal forms.

Henry Moore

Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown (side view)

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown (side view)

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

From plaster to bronze

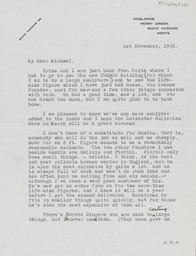

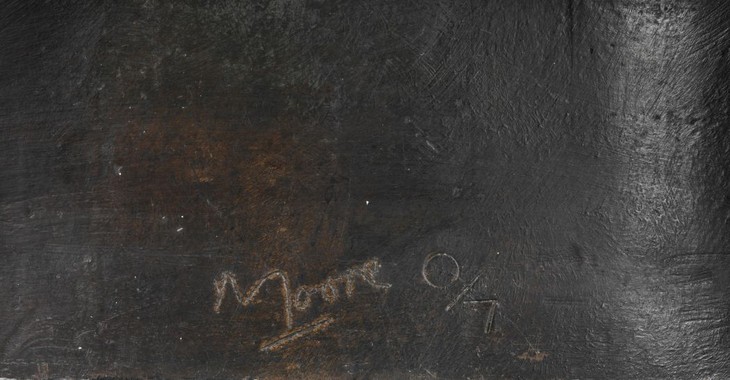

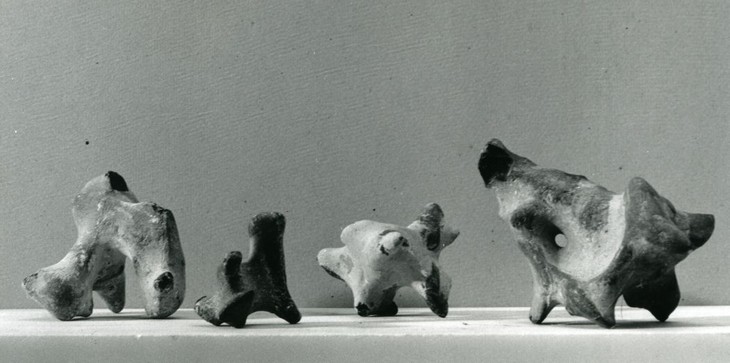

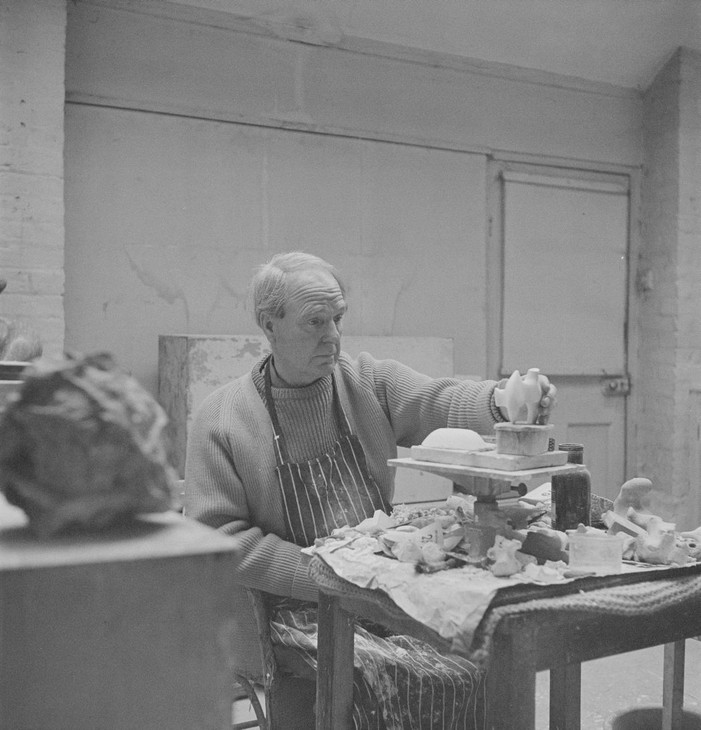

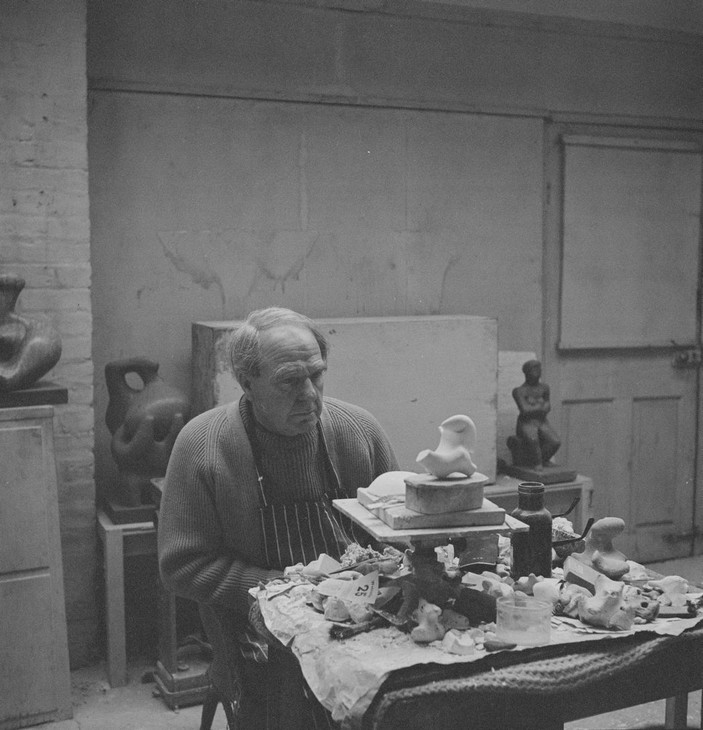

Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer originated from a small hand-held maquette, made in the small sculpture studio on the grounds of Moore’s home, Hoglands, in Perry Green, Hertfordshire (fig.5). By the time Moore made this maquette in 1964 it was common practice for him to begin work on a new sculptural idea with a small plaster model. In 1978 he explained:

I have gradually changed from using preliminary drawings for my sculptures to working from the beginning in three-dimensions. That is, I first make a maquette for any idea I have for a sculpture. The maquette is only three or four inches in size, and I can hold it in my hand, turning it over to look at it from above, underneath, and in fact from any angle.1

Instead of formulating his ideas on paper and then translating them into sculptures, Moore found that by making small models in plaster he could test and develop his designs in three dimensions from the outset. When working on his ideas for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer Moore was particularly focused on the work’s three dimensionality, later stating that ‘the ideas behind a piece like The Archer simply cannot be drawn; its spatial existence is altogether complex. So there are no preliminary drawings for The Archer: the work exists from start to finish in three dimensions’.2 Moore thus sought to create a work that existed in the round, without a definite front or back.

Flint stones in Henry Moore's studio

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.6

Flint stones in Henry Moore's studio

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

I look at them, handle them, see them from all round, and I may press them into clay and pour plaster into that clay and get a start as a bit of plaster, which is a reproduction of the object. And then add to it, change it. In that sort of way something turns out in the end that you could never have thought of the day before.5

It is likely that Moore developed the maquette for this sculpture in just this way, pressing stones into clay and taking plaster casts from the impressions left behind. Once it was dry, he could then modify the plaster by adding and subtracting forms and smoothening or sharpening edges. In 1978 Moore explained why he preferred working in plaster: ‘I use plaster for my maquettes in preference to clay because I can both build it up and cut it down. It is easily worked, while clay hardens and dries, so that it cannot be added to.’6 Unlike many of Moore’s maquettes Archer was never cast in bronze, although Wilkinson recalled that in the early 1970s he ‘found in Moore’s studio a fragment of this maquette for The Archer. Only the top half could be located. The maquette had been broken across the centre, the lower section was missing’.7

Discussing the cast of Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer held in the Cleveland Museum of Art, the curator Edward B. Henning suggested in 1971 that ‘the three ways of the title clearly refer to the three main elements of the work’: the irregular vertical form, the horizontal beam with twin projections and the large, curved wedge.8 However, Wilkinson refuted this explanation, suggesting that the ‘three ways’ in fact indicated the number of different positions in which the sculpture could be placed. Wilkinson supported this proposition with reference to Errol Jackson’s photographs of Moore experimenting with the maquette in his studio. In one photograph Moore holds the maquette in its final position (fig.7), while in another it is resting on its side, with the tip of the wedge tilting upwards to form the sculpture’s tallest point (fig.8).

Errol Jackson

Henry Moore in his studio with Maquette for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.7

Errol Jackson

Henry Moore in his studio with Maquette for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Errol Jackson

Henry Moore in his studio with Maquette for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Errol Jackson

Henry Moore in his studio with Maquette for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Armature for Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer in Moore's studio 1964

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Armature for Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer in Moore's studio 1964

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

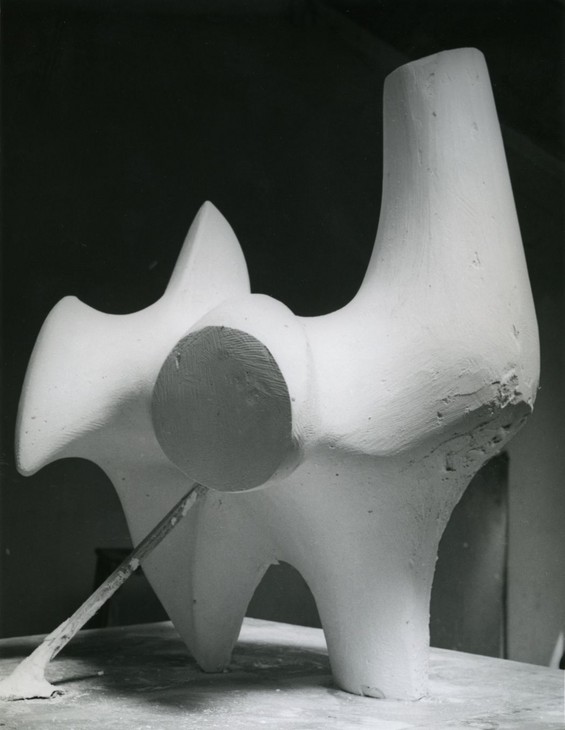

The wooden armature was then draped in scrim, a bandage-like fabric (fig.10). Layers of plaster were then applied on top to achieve the final form. It was at this point that Moore began to work into the plaster surface, using an array of tools including chisels, files and sandpaper. These tools could be used to produce a variety of textures depending on the consistency of the plaster as it dried (fig.11), which were in turn reproduced in the cast bronze. In 1977 the curator Alan Bowness noted that ‘most of the post-war bronzes had rough, variegated textures, but from 1963 or so Moore began to introduce smooth and polished bronze surfaces’, as seen in this work.11 Once Moore was satisfied with the overall shape and surface finish of the plaster it was deemed ready for casting. At this point it is likely that the supporting length of wood was removed and the hole left behind in the plaster was filled in.

Armature for Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer with scrim and plaster 1964

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Armature for Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer with scrim and plaster 1964

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Plaster version of Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer in progress 1964

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Plaster version of Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer in progress 1964

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer was cast in bronze at the Noack Foundry in West Berlin in 1965, and the foundry mark ‘H.NOACK BERLIN’ is stamped on the supporting leg (fig.12). In 1967 Moore stated, ‘I use the Noack foundry for casting most of my work because in my opinion, Noack is the best bronze founder I know ... Also, the Noack foundry is reliable in all ways – in keeping to dates of delivery – and in sustaining the quality of their work’.12 The sculpture was probably made using the sand casting technique, but the finely polished surfaces obscure definitive evidence as to which casting method was used.

A rectangular welding seam on the curved wedge of Tate’s Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer indicates that a patch of bronze was inserted into the sculpture, probably to repair a flaw in the bronze (fig.13). The repair may have originally been imperceptible but welds often become more prominent over time when the metal used to secure the patch has a different chemical composition to the surrounding bronze.

Detail of foundry stamp on Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.12

Detail of foundry stamp on Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of square welding seam Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.13

Detail of square welding seam Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

After it was cast and finished the bronze sculpture was probably then returned to Moore so that he could inspect the quality of the casting and decide how it should be patinated. A patina is the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the pre-heated bronze surface. In 1963 Moore asserted, ‘I always patinate bronze myself’, explaining that since he had conceived the sculpture it would be unlikely that anyone else would be able to replicate the exact colour he wanted.13 However, it is known that over time, as Moore increased his rate of production, technicians at Noack would sometimes patinate his sculptures at the foundry. In these instances Moore was nonetheless able to make later adjustments to the patina in his studio if necessary.

The patina of Tate’s version of Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer is made up of a range of black-brown, reddish-brown and golden shades (fig.14). These colours were probably achieved by using at least two different chemical patina recipes in varying concentrations. At the ‘high points’ or prominent areas of the sculpture, such as the flat faces of the protrusions and curved edges, the patina has been rubbed back to reveal golden tones. The bronze was also lacquered to preserve its range of colours, although the lacquer has broken down over time, causing the patina to appear speckled in certain areas.

Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer was cast in an edition of seven plus one artist’s copy. The artist’s signature and the edition number ‘0/7’ are inscribed on the base, the zero indicating that this work was the artist’s copy (fig.15). A bronze cast of the sculpture was first exhibited in Moore’s solo exhibition at Marlborough Galleria d’Arte in Rome in May 1965. The original plaster is housed in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Other examples of the working model are held in the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C.; the University of Florida Libraries, Gainesville; the Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland; and the Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Other casts are believed to be held in private collections. In 1965 Moore produced a slightly larger version of the sculpture in white marble, which is held in the Didrichsen Art Museum in Helsinki.

Henry Moore

Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.14

Henry Moore

Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.15

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer1964, cast date unknown

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The Toronto commission

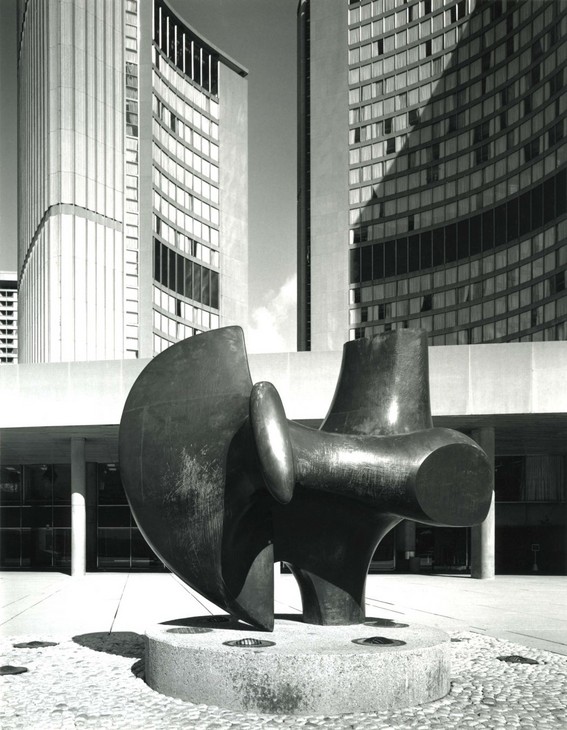

Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1965–6 installed in Nathan Phillips Square, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.16

Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1965–6 installed in Nathan Phillips Square, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Sources and interpretations

As with Working Model for Three Way Piece No.1: Points (Tate T02298), this work was only given its subtitle, ‘Archer’, after its completion. According to the editor of Moore’s catalogue raisonné Alan Bowness, ‘the sub-titles bestowed on these sculptures by the artist ... [are] names of convenience, applied after the work is made, to help distinguish one piece from another’.17 However, Moore later recalled that:

How I came to call it ‘The Archer’ is that the two forms in the middle of the sculpture, not at the top and not at the bottom, in the middle, to me have a kind of stretch in them, and one end is the shape of a bow and this to me at one stage just reminded me of pulling and stretching a bow, and that’s why we call it ‘The Archer’.18

Moore’s identification of a ‘stretching’ and ‘pulling’ motion inferred by the sculpture’s composition not only accounts for its subtitle, but concurs with the ‘modern preference’, noted by art historian Herbert Read in 1964, for ‘forms in dynamic rather than static relationship’.19 For Read, such forms possessed an ‘order’ or inherent logic ‘that proceeds from the balance or significant arrangement of irregular elements’ and enabled the sculptor to convey power and dynamism in static materials.20

In 1964, the same year Moore made his working model, Read identified him as a sculptor principally concerned with the creation of a ‘vital image’,21 and supported this claim with reference to Moore’s 1934 statement for the publication Unit One:

For me a work must first have a vitality of its own. I do not mean a reflection of the vitality of life; of movement, physical action, frisking, dancing figures, and so on, but that a work can have in it a pent-up energy, an intense life of its own, independent of the object it may represent. When a work has this powerful vitality we do not connect the word Beauty with it.22

Read similarly defined vitality as ‘the quality the Chinese call ch’i, the universal force that flows through all things, and which the artist must transmit to his creations if they are to affect other people’.23 For both Moore and Read the term denoted a localised energy, the sculptural expression of which was bound by a set of criteria unrelated to qualities usually associated with conventional aesthetic ‘beauty’ such as harmony, regularity and symmetry. Moore’s concern for the expression of vitality is perhaps reflected by the ‘perplexing’ shapes and impression of ‘something coming to life’ identified by members of the Toronto public when they came to view Three Way Piece No.2: Archer for the first time.

In 1968 the critic and curator David Sylvester concurred with this assessment, noting in Moore’s work of the later 1960s a persistent vitality and ‘pent-up energy’.24 However, he also argued that the dynamism displayed by these works differed from the ‘pent-up energy’ of Moore’s pre-war sculptures, which Sylvester claimed was always ‘firmly contained’.25 What Read identified as a ‘modern preference’ for dynamic forms was in fact, in Sylvester’s view, a development of the 1960s and not directly synonymous with ‘vitality’ as it was defined by Moore in 1937. As such, a work like Recumbent Figure 1938 (Tate N05387) could convey a latent, evenly-distributed force in its large and gently undulating masses, whereas Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer utilises forms that appear to be in constant, active tension. For Sylvester, this ‘emphasis on dynamic rather than static qualities’ in Moore’s work of the later 1960s ‘represented a radically new way of thinking’.26 Sylvester cited Moore at length to support these claims:

It’s the bone that pushes out from the inside; as you bend your leg the knee gets taughtness over it, and it’s there that the movement and energy come from. If you clench a knuckle, you clench a fist, you get in that sense the bones, the knuckles, pushing through, giving a force that, if you open your hand and just have it relaxed, you don’t feel. And so the knee, the shoulder, the skull, the forehead, the part where from inside you get a sense of pressure of the bone outwards – these for me are the key points.27

Sylvester identified the phrases ‘key points’ and ‘pushing through’ as illuminating Moore’s newly articulated interests. He identified ‘passages where the surface is straining to contain something “pressing from the inside trying to burst” suddenly alternate with passages where the pressure is relaxed’.28 Sylvester attributed this shift to ‘a new extreme concentration on tactile and motor rather than visual sensations – on what is experienced in running one’s hands over the body, responding more sharply to its hardness and softness, its hollows and bumps, than when looking at them’.29 For Sylvester, the dynamic variations in the surfaces of the ‘hard and soft’ sculptures demand to be experienced in tactile rather than optical terms, resulting in a sequential, fragmentary experience. He concluded that ‘in no other works has Moore taken such risks. And this reflects a further change of attitude – a growing acceptance, indeed, a positive courting, of imperfection, incompleteness’.30

Stone panel from the North-West Palace of Ashurnasirpal II, Nimrud (ancient Kalhu), northern Iraq 883–859 BC

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.17

Stone panel from the North-West Palace of Ashurnasirpal II, Nimrud (ancient Kalhu), northern Iraq 883–859 BC

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Like the unknown artist of the Assyrian relief, Ashurnasirpal II Killing Lions [fig.17], Henry Moore has translated the subjective ‘feeling’ of vigorous physical action coupled with enduring, monumental form into a particular material. Indeed, it would be easy to believe that he was inspired by the figure of the archer in this ancient Assyrian relief to create Three Way Piece No.2: Archer.31

This relief is held in the British Museum, and as a student in the 1920s Moore drew significant inspiration from its collections. In 1947 he recalled that ‘one room after another in the British Museum took my enthusiasm’, and he went on to record this experience in a publication titled Henry Moore at the British Museum in 1981. 32 In this book, which contained images of fifty objects from the museum’s collection that had had some influence on his work, Moore explained that he associated relief sculptures with painting, since they were not sculpted in the round, and noted, ‘my personal choice in this book does not include relief sculpture, such as the wonderful Assyrian friezes or the Parthenon Frieze’.33 That Moore nonetheless appeared to admire the frieze suggests that it could have served as a source for Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer in the manner Henning described.

In the same text Henning argued that Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer ‘is more complex and varied formally than most works by the artists to whom Moore seems most closely related: Brancusi and Arp’.34 In 1937 Moore had acknowledged that Brancusi’s work had ‘been of historical importance in the development of contemporary sculpture’ but suggested that the way in which Brancusi reduced forms to singular shapes had become too limiting, writing that ‘it may now be no longer necessary to close down and restrict sculpture to the single (static) form unit. We can now begin to open out. To relate and combine together several forms of varied sizes, sections and directions into one organic whole’.35 Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer might be viewed as an example of Moore’s attempt to ‘open out’ the sculptural form in varying configurations and directions that nonetheless formed an integrated whole.

However, Henning concluded that Moore’s project to advance the practice of sculpture was itself limited in comparison to the innovations of other artists, and that he produced work that was ultimately ‘less experimental than the work of artists such as Calder, Gabo, or Anthony Caro – all of whom involve space as an important element in their sculpture’.36 For Henning, Moore’s commitment to working in bronze and the physical density of his sculptures curtailed the experimental scope of his work in comparison to sculptors who had been able to integrate space into their compositions by using lighter, modern materials; plastics in the case of Naum Gabo, and iron and steel in the case of Alexander Calder and Anthony Caro.

Anthony Caro

Wending Back 1969–70

Painted steel

Cleveland Museum of Art

© The estate of Anthony Caro/Barford Sculptures Ltd

Fig.18

Anthony Caro

Wending Back 1969–70

Cleveland Museum of Art

© The estate of Anthony Caro/Barford Sculptures Ltd

The Henry Moore Gift

Installation view of The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, 1978

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.19

Installation view of The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, 1978

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Alice Correia

September 2013

Notes

John Read in Henry Moore: One Yorkshireman Looks at His World, dir. by John Read, television programme, broadcast BBC2, 11 November 1967, http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/henrymoore/8807.shtml , accessed 3 November 2013.

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.217.

Henry Moore in ‘Henry Moore talking to David Sylvester’, 7 June 1963, transcript of Third Programme, BBC Radio, broadcast 14 July 1963, p.18, Tate Archive TGA 200816. (An edited version of this interview was published in the Listener, 29 August 1963, pp.305–7.)

Edward B. Henning, ‘Henry Moore: Three Way Piece No.2: Archer’, Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art, vol.58, no.8, October 1971, p.238.

Julie Summers, ‘Fragment of Maquette for King and Queen’, in Claude Allemand-Cosneau, Manfred Fath and David Mitchinson (eds.), Henry Moore From the Inside Out: Plasters, Carvings and Drawings, Munich 1996, p.126.

See Richard Wentworth, ‘The Going Concern: Working for Moore’, Burlington Magazine, vol.130, no.1029, December 1988, p.928. For a discussion of Moore’s enlargement methods see Anne Wagner, ‘Scale in Sculpture: The Sixties and Henry Moore’, Tate Papers, no.15, spring 2011, http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/scale-sculpture-sixties-and-henry-moore , accessed 13 August 2013.

Anon., ‘What the People Say About “The Archer”’, Toronto Star, 28 October 1966. See http://torontoist.com/2010/07/historicist_henry_moores_big_bronze_whatchamacallit/ , accessed 20 September 2013.

John Warkentin, Creating Memory: A Guide to Outdoor Public Sculpture in Toronto, Toronto 2010, p.160.

Henry Moore, ‘In conversation with Alan Wilkinson, c.1980’, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.295.

Henry Moore, ‘Statement for Unit One’, in Herbert Read (ed.), Unit One, London 1934, pp.29–30, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.192.

Henry Moore cited in James Johnson Sweeney, ‘Henry Moore’, Partisan Review, March–April 1947, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, pp.44–5. In his introduction to the book Henry Moore at the British Museum Moore wrote that ‘It has been a wonderful experience for me to recapture the delight, the excitement, the inspiration I got in these pieces as a young and developing sculptor’. Henry Moore, Henry Moore at the British Museum, London 1981, p.16.

Henry Moore, ‘The Sculptor Speaks’, Listener, 18 August 1937, pp.338–40, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.145.

Anon., ‘Acquisitions of Modern Art by Museums’, Burlington Magazine, vol.114, no.829, April 1972, p.269.

Related essays

- Henry Moore’s American Patrons and Public Commissions Pauline Rose

- Henry Moore and the Values of Business Alex J. Taylor

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

Photograph

-

Photograph

-

Photograph

Related reviews and articles

- Henry Moore, ‘The Sculptor Speaks’ Listener, 18 August 1937, pp.338–40.

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964, cast date unknown by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, September 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www