Henry Moore OM, CH Three Points 1939-40, cast before 1949

Image 1 of 7

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Points 1939-40, cast before 1949© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Points 1939-40, cast before 1949© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Points 1939-40, cast before 1949© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Points 1939-40, cast before 1949© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Points 1939-40, cast before 1949© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Points 1939-40, cast before 1949© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Points 1939-40, cast before 1949© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Points 1939-40, cast before 1949© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Points 1939-40, cast before 1949© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Points 1939-40, cast before 1949© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Points 1939-40, cast before 1949© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Points 1939-40, cast before 1949© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Points 1939-40, cast before 1949© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Points 1939-40, cast before 1949© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Three Points

1939-40, cast before 1949

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

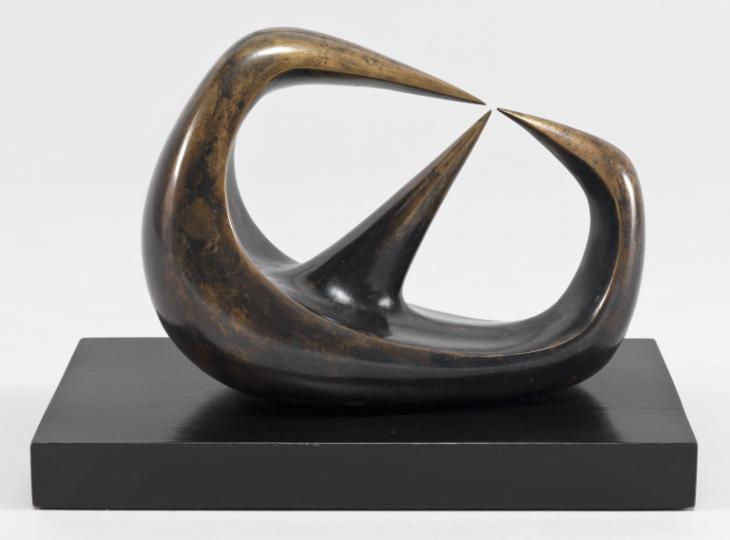

Comprised of three thorn-like forms that converge but do not touch, Three Points has been interpreted by critics as expressing a sense of menace or threat, while Moore himself considered it to animate something akin to an electrical charge. Numerous art historical precedents for the sculpture have been identified, including works by Michelangelo, Picasso and Giacometti, revealing it to be one of Moore’s most widely discussed abstract artworks.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Three Points

1939–40, cast before 1949

Bronze

140 x 190 x 95 mm

Presented by the artist 1978

In an edition of 2 prior to an edition of 8 plus 1 artist’s copy

T02269

Three Points

1939–40, cast before 1949

Bronze

140 x 190 x 95 mm

Presented by the artist 1978

In an edition of 2 prior to an edition of 8 plus 1 artist’s copy

T02269

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1953

Henry Moore, Museum Boymans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, May–July 1953, no.16.

1959

Henry Moore, British Council touring exhibition: Palacio Foz, Lisbon, January–February 1959; School of Fine Arts, Oporto, February–March 1959; Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid, April 1959; Hospital de la Santa Cruz, Barcelona, May 1959, no.8.

1966

Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, New Metropole Arts Centre, Folkestone, April–May 1966 (?another bronze cast exhibited no.17).

1968

Henry Moore, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, May–July 1968; Museum Boymans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, September–November 1968 (?another bronze cast exhibited no.51).

1969

Henry Moore Exhibition in Japan, 1969, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, August–October 1969 (?another bronze cast exhibited no.21).

1975

Henry Moore: Fem Decennier, Skulptur, Teckning, Grafik 1923–1975, British Council touring exhibition: Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter, Oslo, June–July 1975; Kulturhuset, Stockholm, August–October 1975; Nordjyllands Kunstmuseum, Aalborg, October–November 1975 (?another bronze exhibited no.23).

1976

The Work of the British Sculptor Henry Moore, Zürcher Forum, Zürich, June–August 1976 (?another bronze cast exhibited no.22).

1977

Henry Moore: Sculptures et dessins, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris, May–August 1977 (?another bronze cast exhibited no.41).

1978

Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, Cartwright Hall, Bradford, April–June 1978, no.56.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1983

Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, May–September 1983.

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, March–August 1998, no.61.

1998

Henry Moore: Friendship and Influence, Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, Norwich, October–December 1998, no.95.

1999

Surrealism: The Untamed Eye, Works from the Tate Gallery Collection, Norwich Castle Museum, Norwich, July–November 1999, no.25.

2010–11

Henry Moore, Tate Britain, London, February–August 2010; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, October 2010–February 2011; Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds, March–June 2011 no.94.

2012

Picasso and Modern British Art, Tate Britain, London, February–July 2012; Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, August–November 2012, no.88.

References

1940

New Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Leicester Galleries, London 1940 (lead cast reproduced no.64).

1944

Herbert Read (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, London 1944 (lead cast reproduced pl.103b).

1957

David Sylvester (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 1: Complete Sculpture 1921–48, London 1957, no.211.

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960 (lead cast reproduced pl.75 as Three Peaks).

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of His Life and Work, London 1965, p.125 (lead cast reproduced pl.108).

1966

Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, exhibition catalogue, New Metropole Arts Centre, Folkestone 1966.

1968

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo 1968 (?another bronze cast reproduced no.51).

1968

David Sylvester, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1968, pp.36–7 (iron cast reproduced on front cover and p.45, no.37).

1970

Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–1969, London 1970, pp.20–1 (?another bronze cast reproduced no.210).

1972

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Forte di Belvedere, Florence 1972 (iron cast reproduced no.47).

1976

The Work of the British Sculptor Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Zürcher Forum, Zürich 1976 (?another bronze cast reproduced p.135).

1977

Henry Moore: Sculptures et dessins, exhibition catalogue, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris 1977 (?another bronze cast reproduced p.53, no.41).

1977

Alan Wilkinson, The Drawings of Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1977, p.99, reproduced no.12.

1978

Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Cartwright Hall, Bradford 1978, reproduced no.56.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.22.

1979

Alan G. Wilkinson, The Moore Collection in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto 1979, p.204 (another bronze cast reproduced fig.167).

1981

Richard Calvocoressi, ‘T.2269 Three Points’, The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, pp.116–7, reproduced.

1981

Christa Lichtenstern, ‘Henry Moore and Surrealism’, Burlington Magazine, vol.123, no.944, November 1981, pp.644–58.

1981

Anna Gruetzner Robins, ‘The Surrealist Object and Surrealist Sculpture’, in Sandy Nairne and Nicholas Serota (eds.), British Sculpture in the Twentieth Century, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1981, pp.112–23.

1981

Henry Moore: Sculpture, Drawings, Graphics, exhibition catalogue, Palacio de Velázquez, Madrid 1981 (iron cast reproduced nos.155–6). .

1981

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon 1981 (iron cast reproduced no.46).

1981

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona 1981 (iron cast reproduced p.51, no.35).

1983

William S. Lieberman, Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1983, reproduced p.48.

1984

Alan Wilkinson, ‘Henry Moore’, in William Rubin (ed.), Primitivism in Twentieth Century Art, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1984, vol.2, pp.595–614 (another bronze cast reproduced p.607).

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986, exhibition catalogue, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna 1998, pp.304–5, reproduced p.209.

1999

Jennifer Mundy, Surrealism: The Untamed Eye, Works from the Tate Gallery Collection, exhibition catalogue, Norwich Castle Museum, Norwich 1999.

2001

Dorothy Kosinski (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpting the Twentieth Century, exhibition catalogue, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas 2001 (iron cast reproduced pp.39, 50).

2006

Alan Wilkinson, ‘Three Points 1939–40’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, pp.178–9 (iron cast reproduced p.179).

2007

Eric Gibson, ‘Moore and Giacometti’, New Criterion, vol.26, no.4, December 2007, pp.19–22.

2007

Jeremy Lewison, Henry Moore 1898–1986, Cologne 2007 (iron cast reproduced p.49).

2010

Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, reproduced p.163.

2012

Christopher Green, ‘Henry Moore and Picasso’, in James Beechy and Chris Stephens (eds.), Picasso and Modern British Art, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2012, pp.130–49, reproduced p.149.

2013

Richard Calvocoressi, Martin Harrison and Francis Warner, Bacon / Moore: Flesh and Bone, exhibition catalogue, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 2013 (iron cast reproduced p.55).

Technique and condition

Henry Moore

Three Points 1939–40, cast before 1949

Tate T02269

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Three Points 1939–40, cast before 1949

Tate T02269

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Three Points is a small bronze sculpture in which three elongated thorn-shaped points extend from a curved form (fig.1). The bronze is fixed to a rectangular wooden base finished with a thin back lacquer paint that has now developed a finely crackled surface.

Moore would have made a model of the sculpture in clay or plaster from which a mould was taken that was used to cast the sculpture in metal. Other versions of this sculpture exist in lead and iron, and it is possible that the later bronze edition was cast from a mould taken from one of these.

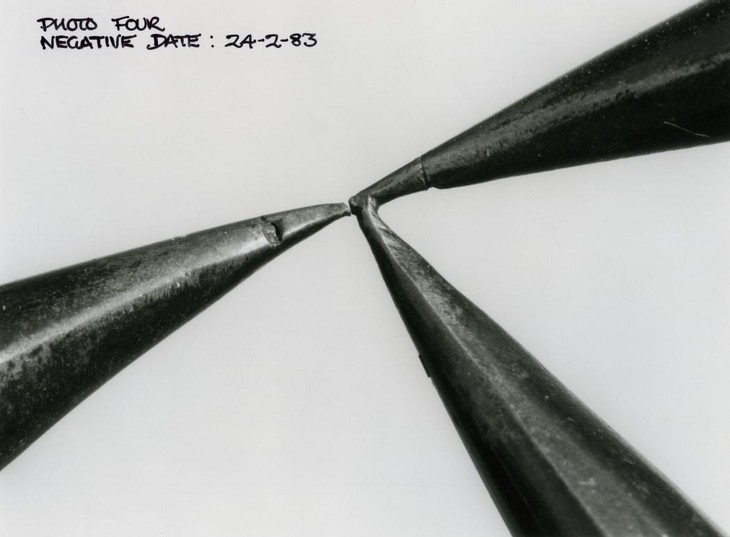

After it was cast the bronze sculpture was filed and sanded until its surface was smooth and polished. There are a number of pinpoint holes in the bronze that are especially visible on the inside of the concave surface (fig.2). These remain from the casting process when gas bubbles escaped from the molten metal. When this sculpture entered the Tate collection in 1978 the three points were actually fused together. This fault was caused during the casting process, so the sculpture was subsequently sent back to Moore so that he could fix it.

The bronze was artificially patinated using a chemical solution called potassium polysulphide (or ‘liver of sulphur’) to achieve its dark, opaque colour. This was stippled onto the metal using a brush, probably while the bronze was heated with a blowtorch. The patina is slightly flakey, which can sometimes result from heating the bronze too strongly. It has been rubbed back with a fine abrasive at the points to produce a gradated effect from gold to dark brown (fig.3).

The bronze is fixed to its base using two flat-headed screws inserted from underneath. No signature is visible, although the sculpture has not been removed from its base for full examination.

Lyndsey Morgan

October 2011

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', October 2011, in Alice Correia, ‘Three Points 1939–40, cast before 1949 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, December 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Three Points is a highly polished, single-piece bronze sculpture mounted on a wooden base (fig.1). It takes the form of a C-shaped wedge positioned on its curved back. The two arms of this shape curve up and arch over the thicker middle from which they grow, converging into two sharpened points that turn towards each other and come within a few millimetres of touching. Running up through the centre of this almost oval composition is another sharp spike, which rises up rigidly towards the two other points and almost meets them.

One arm of the sculpture rises higher than the opposite arm, so that the point extending from the taller side points downwards on a diagonal, while the tip from the shorter side points upwards at the same angle (fig.2). The central conical point also extends on a diagonal from the concave inner surface of the bronze.

Detail of patina on Three Points 1939–40, cast before 1949

Tate T02269

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of patina on Three Points 1939–40, cast before 1949

Tate T02269

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of pinpoint holes on Three Points 1939–40, cast before 1949

Tate T02269

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of pinpoint holes on Three Points 1939–40, cast before 1949

Tate T02269

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The outer surface of the sculpture is smooth and rounded, and does not show any tooling marks, although a number of pinpoint holes can be seen in the inner concave bronze surface (fig.3).

Casting Three Points

Versions of Three Points exist in three different materials: lead, iron and bronze. The first version of Three Points was cast in lead in 1939–40, and it is likely that that this version was one of a number of small metal sculptures cast by Moore and his assistant, Bernard Meadows, in a kiln constructed in the garden at Burcroft, Moore’s cottage in Kent. This practice of ‘backyard casting’ was relatively common among artists making small scale metal sculptures in the 1930s, and lead was a particularly favoured material due to its low melting point. On 9 December 1987 Tate curator Judith Collins interviewed Meadows with particular reference to his role in the creation of Moore’s lead sculptures. She recorded that Meadows ‘remembers casting lead pieces during the summer months of 1938 and 1939’, and that he ‘then stayed on alone at Burcroft in the winter holidays of 1938 and 1939 working on the lead casts’.1

In order to create the lead Three Points it is likely that Moore first made a model of the sculpture in wax. Meadows recalled in 1987 that the wax used for the lead sculptures made between 1938 and 1940 was ‘beeswax, bought from Boots the Chemist’ in Canterbury.2 Having modelled the original wax sculpture it was then encased in a hard material, usually plaster mixed with an aggregate of ground-up pottery. Moore then used the lost wax technique to cast the lead version. This involved heating the sculpture in a kiln until the wax had melted out of the casing before molten lead was poured into the sculpture-shaped void. After the lead had cooled and hardened the outer casing was removed to reveal the sculpture inside. One of the disadvantages of this method was that since the original wax sculpture was lost in the process, there was only one opportunity to cast the sculpture, which meant that if something went wrong, the sculpture would be lost.

It is known that Moore cast at least sixteen lead sculptures at Burcroft between 1938 and 1940. Fourteen of these, including Three Points, were exhibited at his exhibition New Sculpture and Drawings at the Leicester Galleries, London, in February 1940. Although the Second World War put a halt to Moore’s sculptural production, according to records held at the Henry Moore Foundation two bronze versions of Three Points were cast before 1949, one of which became Tate’s copy.3 It is not known which foundry Moore used to cast these two bronze versions, but it is believed that they were cast from a plaster copy taken from the original lead sculpture. In addition to Three Points Moore also cast Reclining Figure 1939 (Tate T03761) in bronze from the original lead version around the same time.

Sometime before 1957 Moore also cast Three Points in iron, and in 1958 Moore cast a further eight examples of the sculpture in bronze, plus an artist’s copy.4 Although Moore later stated that his decision to re-cast earlier lead sculptures was due to the vulnerability of the material and to ‘save the idea’, the decision to re-cast works in multiples may also have been driven by financial reasons.5 By the mid-1950s Moore’s work was in much greater demand from collectors and patrons and re-casting smaller works in editions of eight or nine would have been a practical way of satisfying this increasing demand. At this time Moore worked with a number of different London-based commercial galleries including Roland Browse and Delbanco, Gimpel Fils and the Leicester Galleries, all of which sold small scale sculptures by Moore that could be placed on table tops within the home. In July 1958 Marlborough Fine Art, which had premises in London and New York, became Moore’s principle dealers, and it is believed that this gallery either commissioned or bought out the edition of Three Points cast that year.6

Photograph of fused points dated 24 February 1983

Tate T02269

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Photograph of fused points dated 24 February 1983

Tate T02269

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

It is likely that when the points were separated the patina on the sculpture was also adjusted to reflect the formal changes. A patina is the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the pre-heated bronze. Tate’s version of Three Points has been patinated a dark brown colour, but this was rubbed back at the points to reveal a golden tone that accentuates the sharpened forms. Other areas of the sculpture have a speckled appearance where this lighter underlying colour shows through.

Sources and interpretation

In 1978 Moore explained the ideas behind the composition of Three Points:

In 1940 I made a sculpture with three points [the lead version of Three Points], because this pointing has an emotional or physical action in it where things are just about to touch but don’t. There is some anticipation of this action. Michelangelo used the same theme in his fresco on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, of God creating Adam, in which the forefinger of God’s hand is just about to touch and give life to Adam. It’s also like the points in the sparking plug of a car, where the spark has to jump across the gap between the points. There is a very beautiful early French painting (Gabrielle d’Estrées with her sister in the bath), where one sister is just about to touch the nipple of the other. I used this sense of anticipation first in the Three Points of 1940, but there are other, later works where one form is nearly making contact with the other. It is very important that the points do not actually touch. There has to be a gap.9

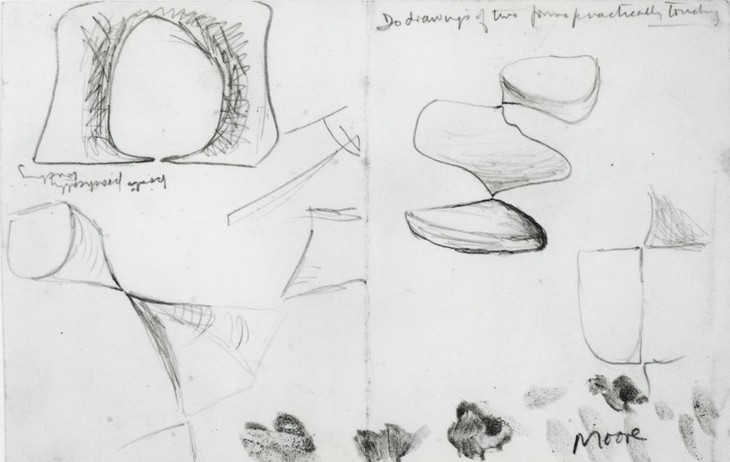

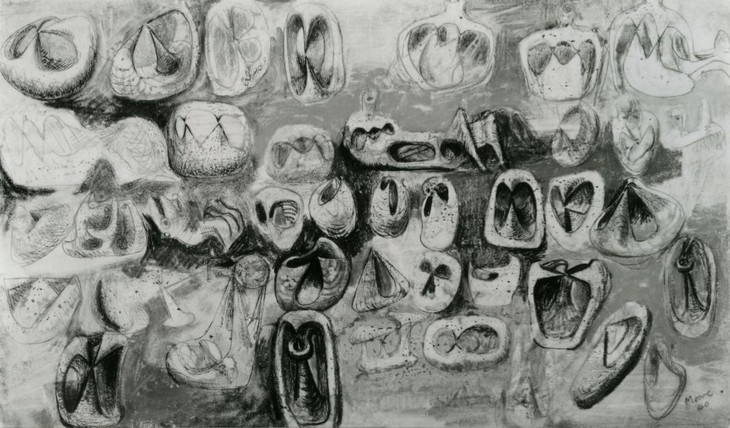

Moore first conceived the idea of a ‘gap’ between which forms are ‘almost touching’ in the late 1930s. The curator Alan Wilkinson has dated Moore’s interest in pointed forms to a sketch from c.1938 titled Drawing for Sculpture with Points, which shows a variety of conical forms pointing towards each other, separated by a gap of a few millimetres (fig.5). Moore annotated the page with the note, ‘do drawings of two forms practically touching’ and the phrase ‘points practically touching’.

Henry Moore

Pointed Forms 1940

Graphite, chalk, crayon, watercolour, pen and ink on paper

Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna

Photo © The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Pointed Forms 1940

Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna

Photo © The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Discussing the sketches contained within Pointed Forms in 1970, the critic Robert Melville agreed with Read’s assessment that ‘all the studies are based on the female breast’.12 He concurred that the breasts of female torsos are transformed into touching points, and went on to suggest that ‘shape-consciousness and idea are inextricably involved in the creation of an image of a “cruel” breast’.13 On looking at Three Points, Melville concluded, ‘we are in the presence of a biomorphic femme fatale’.14 With reference to a Venus flytrap, Melville suggested that ‘the needle-sharp spikes look as if they can retract after making contact. They even convey the impression that their function is to impale, and that they can take likely prey by surprise by withdrawing entirely into the body from which they project’.15 Despite these sexualised readings of the sculpture, Calvocoressi reported that during his conversation with Moore in 1980 the artist ‘used the analogy of the sparking plug’ to convey ‘a sense of anticipation and anxiety’.16

Michelangelo

The Creation of Adam c.1511–12

Sistine Chapel, Vatican

Fig.7

Michelangelo

The Creation of Adam c.1511–12

Sistine Chapel, Vatican

School of Fontainebleau

Presumed Portrait of Gabrielle d'Estrées and Her Sister, the Duchess of Villars c.1594

Oil paint on canvas

960 x 1250 mm

Musée du Louvre, Paris

© 2007 Musée du Louvre / Angèle Dequier

Fig.8

School of Fontainebleau

Presumed Portrait of Gabrielle d'Estrées and Her Sister, the Duchess of Villars c.1594

Musée du Louvre, Paris

© 2007 Musée du Louvre / Angèle Dequier

Pablo Picasso

Horse's Head, Study for Guernica 1937

Oil paint on canvas

650 x 920 mm

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© Succession Picasso/DACS 2015

Fig.9

Pablo Picasso

Horse's Head, Study for Guernica 1937

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© Succession Picasso/DACS 2015

Given that Three Points was made upon the outbreak of the Second World War and has formal connections to Guernica, the associations made by the sculpture, according to art historian Christopher Green, ‘are all of war, death and terror’.27 Green observed that ‘this sculpture’s Guernica resonances are strong enough to ensure that death is kept well in view’.28 Moore’s reluctance to analyse what his friend the art historian Kenneth Clark described as ‘the deep disturbing well from which emerged his finest drawings and sculpture’, may account for the artist’s identification of spark plugs and other non-violent, art historical subjects as sources for Three Points.29 Yet for many critics the sculpture was irredeemably charged with a sense of menace. In 1964 Herbert Read described it as a ‘spicular object’ that illustrated ‘the possibility of endowing an abstract form with an almost vicious animation’.30 And in 2001 the art historian Steven A. Nash concurred that violence was embedded within the sculpture, proposing that it highlights ‘the turbulent side of his [Moore’s] imagination, generally suppressed in later years’.31

Alberto Giacometti

Man and Woman 1928–9

Bronze

400 x 400 x 165 mm

Centre George Pompidou, Paris

© D.R., Adagp, Paris, 2007

Fig.10

Alberto Giacometti

Man and Woman 1928–9

Centre George Pompidou, Paris

© D.R., Adagp, Paris, 2007

Yipwon, Korewori River, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea

National Gallery of Australia

Fig.11

Yipwon, Korewori River, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea

National Gallery of Australia

The Henry Moore Gift

Three Points was presented by Henry Moore to the Tate Gallery in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift. The Gift comprised thirty-six sculptures in bronze, marble and plaster and was exhibited in its entirety alongside Tate’s existing collection of Moore’s work in an exhibition celebrating the artist’s eightieth birthday, which opened in June 1978. A press release was duly prepared announcing that ‘The group [of sculptures] is the most substantial gift of works ever given to the Tate by an artist during his lifetime’.41 Three Points was exhibited in the Duveen Galleries in a wall mounted case alongside Reclining Figure 1939 (Tate T02269). The exhibition was attended by over 20,500 people and nearly 11,000 copies of the catalogue were sold.42 At its close in late August the Director of Tate, Norman Reid, reflected in a letter to Moore’s daughter Mary Danowski that although he was sad to see the exhibition come to an end ‘we have the consolation of the splendid group of sculptures which Henry has presented to the nation’.43

Alice Correia

December 2013

Notes

[Judith Collins], ‘Henry Moore: Reclining Figure 1939’, in The Tate Gallery 1984–86: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions Including Supplement to Catalogue of Acquisitions 1982–84, London 1988, p.539.

211. Henry Moore cited in Donald Carroll, The Donald Carroll Interviews, London 1973, p.42, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.235.

See Richard Calvocoressi, letter to Mrs Tinsley, 31 December 1980, Tate Artist Catalogue File, Henry Moore, A23946. In a letter to Calvocoressi held in the Tate Archive, Moore’s secretary, Mrs Tinsley, referred to the 1958 casts as ‘the Marlborough edition’. See Mrs Tinsley, letter to Richard Calvocoressi, 2 February 1981, Tate Artist Catalogue File, Henry Moore, A23946.

Richard Calvocoressi, ‘T.2269 Three Points’, in The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, p.117.

Richard Calvocoressi, letter to Mrs Tinsley, 4 February 1981, Tate Conservation Records, Henry Moore T02269.

Henry Moore and David Sylvester, ‘The Michelangelo Vision’, Sunday Times Magazine, 16 February 1964, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.157.

Alan Wilkinson, ‘Henry Moore’ in William Rubin (ed.), Primitivism in Twentieth Century Art, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1984, vol.2, p.607.

Henry Moore, ‘Interview with Elizabeth Blunt’, Kaleidoscope, radio programme, broadcast BBC Radio 4, 9 April 1973, transcript printed in Wilkinson 2002, p.167.

Christopher Green, ‘Henry Moore and Picasso’ in James Beechy and Chris Stephens (eds.), Picasso and Modern British Art, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2012, p.149.

Steven A. Nash, ‘Moore and Surrealism Reconsidered’, in Dorothy Kosinski (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century, exhibition catalogue, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas 2001, p.50.

Calvocoressi, ‘T.2269 Three Points’, 1981, p.117. See also Michel Remy, Surrealism in Britain, Aldershot 1999, p.180.

See Anna Gruetzner Robins, ‘The Surrealist Object and Surrealist Sculpture’, in Sandy Nairne and Nicholas Serota (eds.), British Sculpture in the Twentieth Century, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1981, p.120.

Related essays

- Ambivalence and Ambiguity: David Sylvester on Henry Moore Martin Hammer

- Erich Neumann on Henry Moore: Public Sculpture and the Collective Unconscious Tim Martin

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related catalogue entries

Related material

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Three Points 1939–40, cast before 1949 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, December 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www