Henry Moore OM, CH Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954

Image 1 of 6

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Mother and Child

1953, cast c.1954

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Unlike his earlier sculptures representing the loving union between a mother and a child, for this work Moore chose to depict the same two figures as alien, animalistic creatures locked in violent struggle.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Mother and Child

1953, cast c.1954

Bronze on a wood base

510 x 230 x 235 mm

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1960

Second artist’s copy aside from edition of 7 plus 1 artist’s copy

T00389

Mother and Child

1953, cast c.1954

Bronze on a wood base

510 x 230 x 235 mm

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1960

Second artist’s copy aside from edition of 7 plus 1 artist’s copy

T00389

Ownership history

Acquired directly from the artist by the Friends of the Tate Gallery, by whom presented to Tate in 1960.

Exhibition history

1962

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings, Arts Council Gallery, Cambridge, February–March 1962 (?another cast exhibited no.21).

1973

Henry Moore to Gilbert & George: Modern British Art from the Tate Gallery, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, September–November 1973, no.41.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, March–August 1998, no.27.

2005

Henry Moore y México, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City, June–October 2005, no.40.

2010

Henry Moore, Tate Britain, London, February–August 2010, no number.

2011–12

Relative Values: The Family in British Art, Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, Norwich, October 2011–January 2012; Millennium Gallery, Sheffield, February–April 2012; Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne, May–September 2012.

References

1954

New Bronzes by Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Leicester Galleries, London 1954 (another cast reproduced no.5).

1954

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Curt Valentin Gallery, New York 1954 (another cast reproduced no.25).

1959

Erich Neumann, The Archetypal World of Henry Moore, London 1959, p.117 (?another cast reproduced pl.91).

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960, p.143.

1965

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 2: Sculpture and Drawings 1949–1955, 1955, 2nd edn, London 1965, no.315, pl.41.

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965 (?another cast reproduced pl.156, p.176).

1970

Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–69, London 1970 (?another cast reproduced no.469).

1974

Henry Moore, ‘Henry Moore Talks About his Life as a Sculptor’, Listener, 24 January 1974, p.105.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.31.

1979

Alan G. Wilkinson, The Moore Collection in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto 1979 (plaster maquette reproduced p.119).

1987

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, pp.141–2 (plaster maquette reproduced p.141).

1992

Julian Stallabrass, ‘Henry Moore: Mother and Child’, in Henry Moore: Mutter und Kind / Mother and Child, exhibition catalogue, Käthe Kollwitz Museum, Cologne 1992, http://www.courtauld.ac.uk/people/stallabrass_julian/PDF/Moore.pdf, accessed 13 December 2013.

1999

Anne Wagner, ‘Henry Moore’s Mother’, Representations, no.65, winter 1999, pp.93–120.

2000

Barbara Braun, Pre-Columbian Art and the Post-Columbian World: Ancient American Sources of Modern Art, New York 2000 (plaster original reproduced p.129).

2006

David Cohen, ‘Maquette for Mother and Child 1952’ in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, pp.233–5.

2010

Gregor Muir (ed.), Henry Moore: Ideas for Sculpture, exhibition catalogue, Hauser & Wirth, London 2010, p.150 (another cast reproduced p.151).

2010

Lyndsey Stonebridge, ‘A Love of Beginnings: Henry Moore and Psychoanalysis’ in Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, pp.40–9 (reproduced p.45).

Technique and condition

Henry Moore

Mother and Child 1953

Plaster

Art Gallery of Ontario

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Mother and Child 1953

Art Gallery of Ontario

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore cast this small sculpture in bronze from an original model made of plaster (fig.1). This model was created by applying successive layers of wet plaster over an armature, probably made of metal, which provided support for the thinner, more delicate parts of the sculpture, such as the legs of the bench and the child’s long neck. The surface of the bronze reveals the techniques Moore used to shape the forms. Tool marks in the mother’s lap were made while the plaster was still wet, while parallel marks on the legs of the bench, the woman’s left arm, and the child’s right shoulder were made using a saw blade or file while the plaster was drying. Vertical striations can also be seen between the legs of the woman and on one side of the child’s head.

When it was finished the plaster model was sent to the Art Bronze Foundry in London where a mould was taken into which molten bronze was poured. The small size and detailed nature of the surface suggest that it was most likely cast using the lost wax technique, probably in one piece. After casting the bronze would have been cleaned and any defects would have been repaired. There is no evidence of any other post-cast finishing, which indicates that the original marks made in the surface of the plaster were reproduced in the finished bronze. The bronze was patinated artificially by applying chemical solutions onto the surface in layers with a brush. These reacted with the metal to produce coloured compounds. The brown colours of this sculpture were probably made using potassium polysulphide. The high points have been rubbed back to expose lighter shades underneath, which contrast with the darker recesses. A wax has been applied to the surface to protect the bronze.

The wooden base is covered with a copper sheet, which is fixed underneath with copper nails. There are a number of holes in the underside of the base, which suggest it may previously have been used for another purpose. The sculpture has been fixed to the base using brass screw threads that run through the feet of the woman and through one of the legs of the bench. These are secured with nuts. There are no inscriptions on the sculpture.

Lyndsey Morgan

January 2014

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', January 2014, in Alice Correia, ‘Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, November 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

This small bronze sculpture depicts a thin, angular woman seated on a bench with a smaller serpentine figure who rises up from her left hip. This figure, which the title indicates is a child, lunges forward with a gasping mouth towards the woman’s almost spherical breast, but appears to be held back by the woman’s left hand, which is clasped tightly around the child’s long neck. This sense of struggle, coupled with the sharp, pointed features of both figures, transforms the traditional subject of the mother and child from one of nurture and protection to one characterised by violence and attack.

The mother sits on the two-legged bench with her legs pressed closely together and her feet planted firmly on the base (fig.1). Her right thigh connects to her thin, upright torso, which appears twisted to face the child. A circular depression on the right side of her chest is suggestive of an inverted or depleted breast, in contrast to her left breast, which is round and plump. The woman only has one short, tubular arm, which extends from the left side of her body towards the child. Her shoulders are wider than her torso and connect to a thin, elongated head marked by a line of four pyramidal points directed at the child. The sense of menace evoked by these sharp, teeth-like forms is heightened by four more raised ridges on the right side of her face.

Henry Moore

Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954

Tate T00389

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954

Tate T00389

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954

Tate T00389

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954

Tate T00389

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The child, which has no recognisably human features, is conjoined to the mother’s left hip, from which its thin body rises to a hollow, wheel-like form, which may represent an empty stomach. From here the child’s long, tubular neck extends up to a schematic bird-like head with a pointed crest and an open beak-like mouth, which thrusts towards the mother’s breast as though to feed (fig.2). Only the mother’s tight grip around the child’s neck appears to stop the child from biting her. The child’s large circular eyes, positioned on either side of its head, intensify the impression that it is straining, either from its compulsion to feed, or from the pain exerted by the mother’s stranglehold.

Origins and facture

Mother and Child originated from a drawing made by Moore in 1950–1, by which time he had already developed a keen interest in the subject of the mother and child, which preoccupied his work of the later 1940s. His page of sketches titled Studies for Mother and Child (fig.3) depicts four seated mothers, each holding a child, rendered to varying degrees of completeness. The sketch in the lower left of the page depicts a bird-like child lunging at the mother’s rounded breast while she attempts to hold the child away from her body. It is remarkable how closely Moore followed this initial depiction in his final sculpture; the jagged face of the mother, the conjoined bodies, and the two-legged bench have all been reproduced in the final bronze. The only significant difference between the drawing and the sculpture appears to be the orientation of the mother’s legs in relation to her body. In the sketch the legs face towards her right rather than to the front.

Henry Moore

Maquette for Mother and Child 1952

Bronze

216 x 134 x 101 mm

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Maquette for Mother and Child 1952

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Mother and Child 1953

Plaster

Art Gallery of Ontario

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Mother and Child 1953

Art Gallery of Ontario

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore’s first three-dimensional development of this idea took the form of a small maquette, probably made of clay or wax. According to the artist’s daughter Mary Moore this maquette was cast in bronze in the furnace built in 1950 at the bottom of the garden of Moore’s home, Hoglands, at Perry Green in Hertfordshire (fig.4). In the late 1930s Moore had cast a series of small lead sculptures, including Reclining Figure 1939 (Tate T03761), in the garden of his then home in Kent, and so had some metalwork experience when he decided to return to backyard casting in 1950. Moore had used professional foundries to cast his bronze sculptures during the 1940s, but the expense of this process, coupled with his stated ambition ‘to know how bronze casting was done’, may have prompted him to try it himself.1 However, according to his friend and former assistant Bernard Meadows, Moore’s garden foundry at Hoglands ‘never really worked because the furnace didn’t get hot enough to melt the bronze!’2 According to Mary Moore, when Moore removed the bronze Maquette for Mother and Child from its mould, ‘there were ragged edges of bronze on the mother’s head of the type you’d ordinarily file off. He enjoyed them so much he not only left most of them on, by accentuated them when he created the larger form. So it was happenstance that led him to those really pointed edges’.3 While the first bronze version of Maquette for Mother and Child was cast at Hoglands, it was also later cast in bronze in an edition of nine at the Art Bronze Foundry in London.

Moore would have used this maquette as a guide when it came to enlarging the sculpture into the full-size plaster version from which the bronze edition could be cast (fig.5). The enlargement process was probably carried out in the White Studio at Hoglands by one of Moore’s assistants, who in 1953 were Pete Atkins, Anthony Caro, Alan Ingham, Peter King and Philip McCracken. First, an internal armature was constructed to the required size and shape, most likely using lengths of wire.4 Layers of plaster were then layered over the armature struts until the sculpture began to gain mass and form. Moore would have taken over at the final stage of fabrication to make any necessary adjustments and produce the surface texture. Various markings on the surface of the bronze suggest that Moore used a variety of tools to create different forms and textures. Parallel vertical lines on the inside surface of the triangular bench leg are suggestive of a claw tool, while the sharper angled shapes of the two heads were probably filed when the plaster was dry.

Once the plaster was complete it was sent to the Art Bronze Foundry in London to be cast in bronze. The foundry technicians would use the plaster sculpture to create a hollow mould into which molten bronze could be poured and from which multiple bronze casts could be made. Mother and Child was originally cast in an edition of seven, plus one artist’s copy. At some point in 1954 Moore allowed an extra example of the sculpture to be cast specially for Tate.

After it had been cast the bronze sculpture was returned to Moore so that he could check the quality of casting and make decisions about the patination. A patina is the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the pre-heated bronze surface. Tate’s Mother and Child has a fairly even chocolate-brown patina, probably made using potassium polysulphide.

Intention and interpretation

In 1974 Moore explained his intentions behind making Mother and Child:

I’ve done many mother and child sculptures, and most of them have this idea of the larger form in a protective relationship with the smaller form – the sense of gentleness and of tenderness. But this isn’t always so with youth and age. It isn’t always so with very young children or animals. They’re ravenous. It’s as though they want to devour their parent: their need for food, for growing, is such that they have no tender feelings towards the parent. Sometimes the parent has almost to protect itself – and this is the opposite side to what I usually did in my mother and child ideas. I wanted this to seem as though the child was trying to devour its parent – as though the parent, the mother had to hold the child at arm’s length.5

Henry Moore

Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944–5

Tate N05603

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944–5

Tate N05603

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In 1965 the critic Herbert Read recognised that Mother and Child ‘assumes a more sinister aspect [than Moore’s earlier examples of the subject] ... in which the child is seen aggressively attacking the mother’s breast with its gaping, bird-like beak while the mother’s terror is expressed in a sharply serrated head’.7 Five years earlier the critic Will Grohmann had discussed what he regarded as the disturbing aspect of Moore’s sculpture:

two concavely modelled beings sit facing one another on a Delphic tripod like birds of prey, forced into a semicircular unity ... The child is seeking with its bird’s beak for its mother’s breast, although it cannot drink but only wound; the jagged comb of the mother’s face is deadly, not even human, let alone motherly; the theme turns into its opposite, the human or divine into the diabolical.8

Perhaps because of its violent subject matter Mother and Child was one of the few sculptures that scholars attempted to read in psychoanalytical terms during Moore’s lifetime. Read suggested that:

the group is so close an illustration of the psycho-analytical theories of Melanie Klein that it might seem the sculptor has some first-hand acquaintance with them; but the artist assures me that this is not so. It may be that, in Neumann’s words, ‘it is a picture of the Terrible Mother, of the primal relationship fixed forever in its negative aspect’, but if so, it is a picture that comes from the artist’s unconscious: it has no direct connections with any psycho-analytical theory.9

Melanie Klein (1882–1960) had become a leading figure in British psychoanalysis after moving to London from Berlin in 1926. Following the work of Sigmund Freud, Klein pioneered psychoanalytic techniques for children and explored aggressive tendencies related to envy, hate and greed. According to the scholar Lyndsey Stonebridge, ‘Moore’s mothers and their children were not so much the visual correlates of the theory [of Klein], as reminders of what psychoanalysis itself was trying to describe’.10 Art critic David Cohen has noted that Klein introduced the idea that a child can split the notion of its mother into ‘a good breast and a bad breast, depending on when and whether the mother is there to satisfy his needs’.11 With regard to Mother and Child, Cohen has observed that ‘the way in this work one breast projects and the other caves in provides food for Kleinean thought’.12

Despite and perhaps because Moore insisted that the work of Klein had not directly informed the ideas behind Mother and Child, Read cited the work of German psychologist Erich Neumann to endorse a psychoanalytical account of the sculpture. In his 1959 publication The Archetypal World of Henry Moore, Neumann regarded Mother and Child:

as perhaps the most negative expression of the mother-and-child idea in the whole of Moore’s work. The birdlike child snapping at the breast is a motif whose significance lies in the fact that the gaping beak never gets what it wants ... The spiky head of the woman reinforces the negativism of her attitude. It is a picture of the Terrible Mother, of the primal relationship fixed forever in its negative aspect. Once again the artist’s intuition has given shape to an archetypal situation: the eternal and insatiable longing of those who are bound to a negative mother. Just as in the positive relationship the child is shown firmly rooted in the mother and the in world, so in the negative relationship it is shown thrust away from the mother and suspended almost rootlessly in the air.13

Although Moore was sent a copy of Neumann’s book, he famously refused to read it, not wanting to know how his mind worked.14 In addition to the violence contained within the sculpture, what distinguishes the 1953 Mother and Child from most of Moore’s other examples of the subject is the depiction of breastfeeding.15 However, unlike historical artworks that depicted this act, such as Titian’s The Virgin Suckling the Infant Christ c.1565–75 (National Gallery, London) and Aimé-Jules Dalou’s Peasant Woman Nursing a Baby 1873 (Victoria and Albert Museum, London) – with which Moore would have been familiar – in his own work he transforms the subject from one of nurture and nourishment to one of aggression and brutality.16

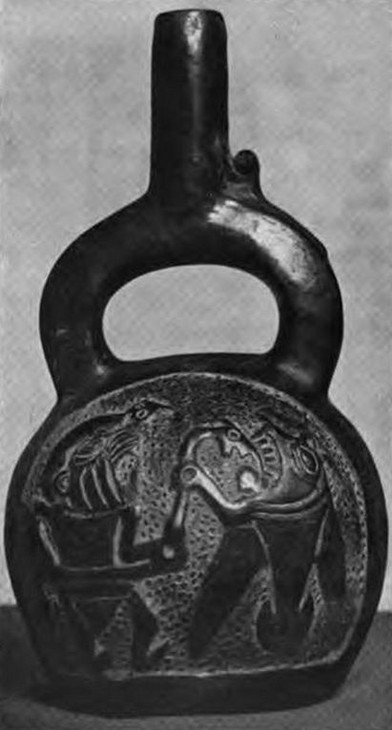

Chimú blackware pot c.800–1300 AD, Peru

Museum fur Volkerkunde, Vienna

Fig.7

Chimú blackware pot c.800–1300 AD, Peru

Museum fur Volkerkunde, Vienna

Cohen has also suggested that the sculpture ‘relates keenly to the Zeitgeist and to contemporary developments in sculpture’.20 In 1952 a group of young British sculptors, including Kenneth Armitage, Reg Bulter, Lyn Chadwick, Bernard Meadows and Eduardo Paolozzi, were selected to represent Britain at the Venice Biennale. Works such as Butler’s Woman 1949 (Tate N05942) and Meadows’s Black Crab 1951–2 (Tate T03409) presented angular, threatening figures and in the exhibition catalogue Herbert Read described such works as manifestations a collective post-war anxiety.21 Read went on to identify Moore as the ‘father of them all’, and outside the British pavilion his large-scale angular Standing Figure 1950 (see Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, Tate T06827) stood guard. 22 Discussing Mother and Child in 1963 the critic John Russell echoed these sentiments stating,

Even the hallowed theme of Mother & Child takes on, in one large piece, a new dimension of psychic reality when we realise that the child is in fact threatening to tear its mother to pieces. Moore has abandoned, in short, the pacific view of family-relationships which won him such popularity in the late 1940s and has been aiming to get an ever more powerful dramatic tension into his large pieces. The full hostility of our environment is coming through: the fact, that is to say, that everything around us tends sooner or later towards our destruction: Nature, other people, and ourselves.23

Henry Moore and the Tate collection

Tate held thirteen sculptures by Henry Moore in its collection prior to the acquisition of Mother and Child in 1960. Since a large number of these were small maquettes, by the late 1950s the Trustees of the Tate were keen to expand the gallery’s holdings of Moore’s work. Acquisitions of Moore’s work had been hindered since the 1930s, first by J.B. Manson, Tate’s director between 1930 and 1938, who disliked modern art and who told Tate trustee Robert Sainsbury ‘Over my dead body will Henry Moore ever enter the Tate’,24 and then by Moore’s subsequent post as a trustee of the gallery from 1941–8 and then 1949–56.25

After stepping down from his role as a trustee, Moore discussed a number of sculptures that could be made available to Tate with the gallery’s then director, Sir John Rothenstein. Moore proposed a list of eight works, which was presented to the trustees at their meeting on 16 May 1957.26 Although this proposed purchase did not occur immediately, the list, which included an example of each of Moore’s different subjects and materials to date, became the blueprint used by the Friends of the Tate for their acquisition of six sculptures by Moore in 1960. A letter to Moore dated 1961 from Jane Lascelles, Organising Secretary for the Friends, notes that there was no correspondence about the acquisition of these sculptures in the Friends’ files, suggesting that the particulars of the sale, including prices, were agreed verbally with Moore.27 In addition to Mother and Child, the other sculptures presented to the gallery in December 1960 were Composition 1932 (Tate T00385), Stringed Figure 1938, cast 1960 (Tate T00386), Reclining Figure 1939, cast 1959 (Tate T00387), Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960 (Tate T00388) and Working Model for Unesco Reclining Figure 1957, cast 1959–60 (Tate T00390).

In 1978 Mother and Child was included in an exhibition of Moore’s work at the Tate Gallery, held to celebrate the artist’s eightieth birthday (fig.8). On the occasion of this show the writer Roger Berthoud described the sculpture as ‘chilling ... A claw-headed baby menaces the breast, the mother’s grip on it is rigid with fear, or perhaps hate’.28 Perhaps to temper these feelings of anxiety, the sculpture was exhibited alongside the benign large-scale plaster sculpture Seated Woman 1957 (Tate T02279), which has been interpreted as a pregnant woman. Held between June and August, the exhibition was attended by over 20,500 people and nearly 11,000 copies of the catalogue were sold.29

Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954 on display in the exhibition The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery in 1978

Tate Archives

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954 on display in the exhibition The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery in 1978

Tate Archives

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Other bronze casts of the sculpture are held in the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C., and the Henry Moore Family Collection. The original plaster is held in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. The remaining casts are believed to be held in private collections.

Alice Correia

November 2013

Notes

In 1960 Moore explained why he built the furnace in his garden: ‘at one period of my career I thought I ought to know how bronze casting was done, and I did it myself at the bottom of the garden, along with my two assistants. We built a foundry in miniature of our own, and throughout one year I cast some eight or ten things into bronze’. See Donald Hall, ‘Henry Moore: An Interview by Donald Hall’, Horizon, November 1960, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.232.

Mary Moore, ‘Mother and Child’, in Gregor Muir (ed.), Henry Moore: Ideas for Sculpture, exhibition catalogue, Hauser & Wirth, London 2010, p.150.

Wire was used to make the armatures of other small sculptures at this time, such as Maquette for Standing Figure 1950 (Tate T06827).

Lyndsey Stonebridge, ‘A Love of Beginnings: Henry Moore and Psychoanalysis’, in Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, p.41.

David Cohen, ‘Maquette for Mother and Child 1952’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, p.233.

Moore had represented the subject before with Suckling Child 1930 (Pallant House Gallery, Chichester).

For Titian’s The Virgin Suckling the Infant Christ c.1565–75 see http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/titian-the-virgin-suckling-the-infant-christ , accessed 9 December 2013. For Aimé-Jules Dalou’s Peasant Woman Nursing a Baby 1873 see http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O34921/peasant-woman-nursing-a-baby-figure-group-aime-jules-dalou/ , accessed 9 December 2013.

Barbara Braun, Pre-Columbian Art and the Post-Columbian World: Ancient American Sources of Modern Art, New York 2000, p.95.

Herbert Read, ‘New Aspects of British Sculpture’, in Exhibition of Works by Sutherland, Wadsworth, Adams, Armitage, Butler, Chadwick, Clarke, Meadows, Moore, Paolozzi, Turnbull. Organised by the British Council for the XXVI Biennale, Venice, exhibition catalogue, British Pavilion, Venice Biennale, Venice 1952.

See Jennifer Powell, ‘A Coherent, National “School” of Sculpture? Constructing Post-War New British Sculpture through Exhibition Practices’, Sculpture Journal, vol.21, no.2, 2012, pp.37–50.

John Russell, ‘Introduction’, in Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Art Center in La Jolla, La Jolla 1963, unpaginated.

Minutes of Meeting of the Trustees of the Tate Gallery, 16 May 1957, Tate Public Records TG 4/2/742/2.

Related essays

- 'I tried to push him down the stairs': John Berger and Henry Moore in Parallel Tom Overton

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related catalogue entries

Related material

Related bibliography

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Mother and Child 1953, cast c.1954 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, November 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www