Henry Moore OM, CH Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6

Image 1 of 15

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964-6© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Moon Head

1964, cast c.1964-6

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

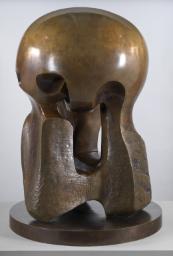

Moon Head 1964 is a bronze sculpture that explores notions of thinness and relates closely to Moore’s Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece, completed two years earlier. Another cast of the sculpture was patinated a golden colour and reminded Moore of the light and shape of the moon.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Moon Head

1964, cast c.1964–6

Bronze

578 x 442 x 255 mm

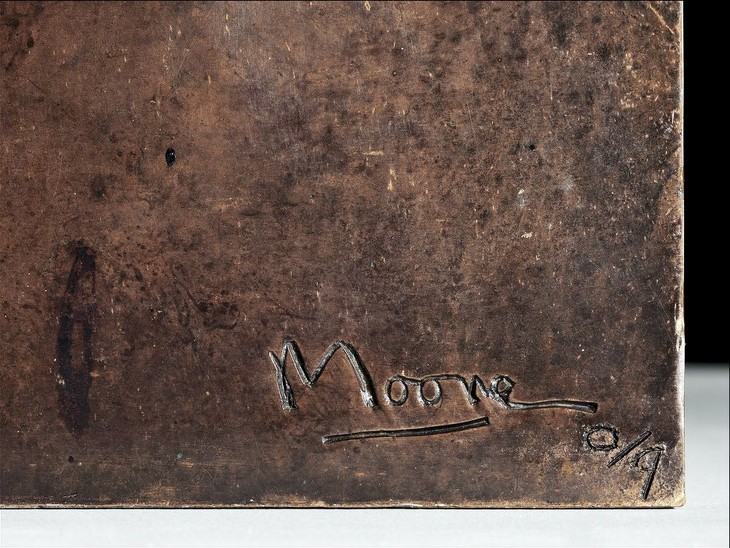

Inscribed ‘Moore 0/9’ on base and stamped ‘H. NOACK BERLIN’ on lower edge of sculpture

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s copy aside from an edition of 9

T02297

Moon Head

1964, cast c.1964–6

Bronze

578 x 442 x 255 mm

Inscribed ‘Moore 0/9’ on base and stamped ‘H. NOACK BERLIN’ on lower edge of sculpture

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s copy aside from an edition of 9

T02297

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1965

British Sculpture in the Sixties: An Exhibition Organised by the Contemporary Art Society in Association with the Peter Stuyvesant Foundation, Tate Gallery, London, February–April 1965 (?another cast exhibited no.78).

1966

Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, New Metropole Arts Centre, Folkestone, April–May 1966, no.10.

1968

Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1968, no.132.

1969

Henry Moore, Heslington Hall, York, March 1969, no.35.

1971

Henry Moore 1961–1971, Staatsgalerie Moderner Kunst, Munich, October–November 1971, no.7.

1972

Mostra di Henry Moore, Forte di Belvedere, Florence, May–September 1972, no.130.

1975

Henry Moore: Fem Decennier, Skulptur, Teckning, Grafik 1923–1975, British Council touring exhibition: Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter, Oslo, June–July 1975; Kulturhuset, Stockholm, August–October 1975; Nordjyllands Kunstmuseum, Aalborg, October–November 1975, no.69.

1976

The Work of the British Sculptor Henry Moore, Zürcher Forum, Zürich, June–August 1976, no.76.

1978

Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, Cartwright Hall, Bradford, April–June 1978, no.37.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1981

Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings, Graphics 1921–1981, Palacio de Velázquez, Palacio de Cristal and Parque de El Retiro, Madrid, May–August 1981, no.42.

1981

Henry Moore, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, September–November 1981, no.104.

1982

Henry Moore: Head-Helmet, DLI Museum and Arts Centre, Durham, June–July 1982, no.35.

1983

Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, May–September 1983, no number.

1984–5

Primitivism in Twentieth Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern, Museum of Modern Art, New York, September 1984–January 1985; Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, February–May 1985; Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, June–September 1985, no number.

1987

Henry Moore in India: Exhibition of Sculptures, Drawings and Graphics, National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi, October–November 1987, no.82.

1991

Henry Moore: The Human Dimension, Benois Museum, Petrodvorets, St Petersburg, June–August 1991; Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, September–October 1991, no.91.

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, March–August 1998, no.75.

2005

Henry Moore y México, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City, June–October 2005, no.49.

References

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, p.244 (another cast reproduced pl.234).

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, p.209 (another cast reproduced nos.218–19).

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.466–7 (another cast reproduced p.443).

1968

David Sylvester, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1968, p.119 (?another cast reproduced p.121, pls.108–9).

1977

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 4: Complete Sculpture 1964–73, London 1977 (?another cast reproduced pls.14–15).

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.56.

1979

Alan G. Wilkinson, The Moore Collection in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto 1979, p.186 (original plaster reproduced pl.166).

1981

The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, pp.137–8, reproduced p.137.

1981

Henry Moore at the British Museum, London 1981 (porcelain cast reproduced p.47).

1981

Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Gauguin to Moore: Primitivism in Modern Sculpture, exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto 1981.

1984

Alan Wilkinson, ‘Henry Moore’, in William Rubin (ed.), Primitivism in Twentieth Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern, vol.2, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1984, pp.595–613, reproduced p.611.

1987

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987 (original plaster reproduced p.210).

1998

John Hedgecoe, A Monumental Vision: The Sculpture of Henry Moore, London 1998 (another cast reproduced pp.156–7).

1991

Henry Moore: The Human Dimension, exhibition catalogue, Benois Museum, Petrodvorets 1991, reproduced p.116 and front cover.

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986, exhibition catalogue, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna 1998, reproduced p.223.

2000

Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece, exhibition catalogue, Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation Museum of Contemporary Art, Andros 2000, p.160 (porcelain cast reproduced no.33).

2005

Henry Moore y México, exhibition catalogue, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City 2005, reproduced p.79.

2006

David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, pp.279–80 (porcelain cast reproduced p.279).

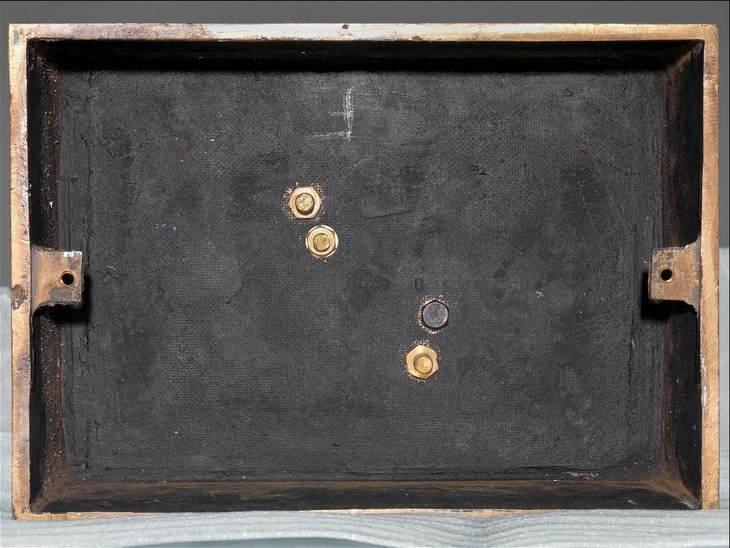

Technique and condition

This abstract bronze sculpture consists of two vertically orientated disc-like shapes that each rise from a broad stem or neck mounted on a rectangular bronze base. The thin round shapes are positioned a short distance apart in front of each other but not in direct alignment so that one can always be seen behind the other.

To make this sculpture in bronze Moore first made a plaster model based on a smaller maquette he had created a few years previously. It is likely that the plaster model was built up over an armature of wood and wire, and then worked with files and other tools before its surfaces were smoothed with sandpaper. The full-size plaster model was then sent to the Noack Foundry in West Berlin, where it was cast in bronze.

The surfaces of the two discs reveal little as to whether they were created using the sand casting or lost wax casting technique. However, it is likely that they were sand cast because this was the preferred technique of the Noack Foundry and the smooth shapes of this sculpture lend themselves to sand casting. This process involves making a two-part mould of each component of the sculpture using a mixture of sand and clay or resin, which is then baked or hardened using a chemical process. The two parts of each mould are then fitted together to create a hollow cavity into which molten bronze can be poured. This casting method leaves at least two mould seams on the final sculpture, which can be removed after the bronze has cooled.

According to notes held at the Henry Moore Foundation the base of Moon Head was cast in London at the Art Bronze Foundry. Simple shapes like this were normally sand cast, and in this case it appears that the box used as the model was made out of fibreboard, for the finely chequered pattern of the fibreboard appears to have been reproduced on the underside of the base (fig.1). The two discs are attached to the base with three threaded rods and nuts, and one bolt.

Detail of patina on Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964–6

Tate T02297

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of patina on Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964–6

Tate T02297

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of lacquer on Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964–6

Tate T02297

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of lacquer on Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964–6

Tate T02297

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

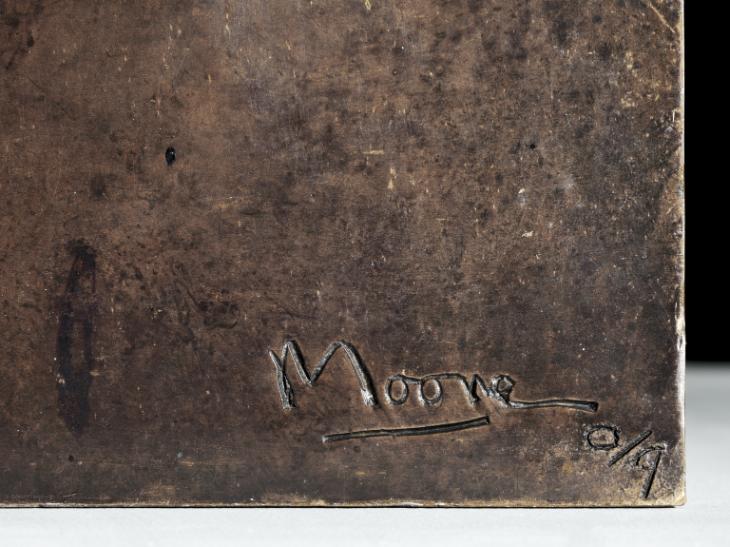

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on base of Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964–6

Tate T02297

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on base of Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964–6

Tate T02297

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

This work exists in an edition of nine plus one artist’s cast. Tate’s sculpture is signed ‘Moore’ and numbered ‘0/9’ on the base, indicating that this was originally the artist’s copy (fig.4).

Rozmarijn van der Molen

March 2014

How to cite

Rozmarijn van der Molen, 'Technique and Condition', March 2014, in Alice Correia, ‘Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964–6 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, March 2014, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

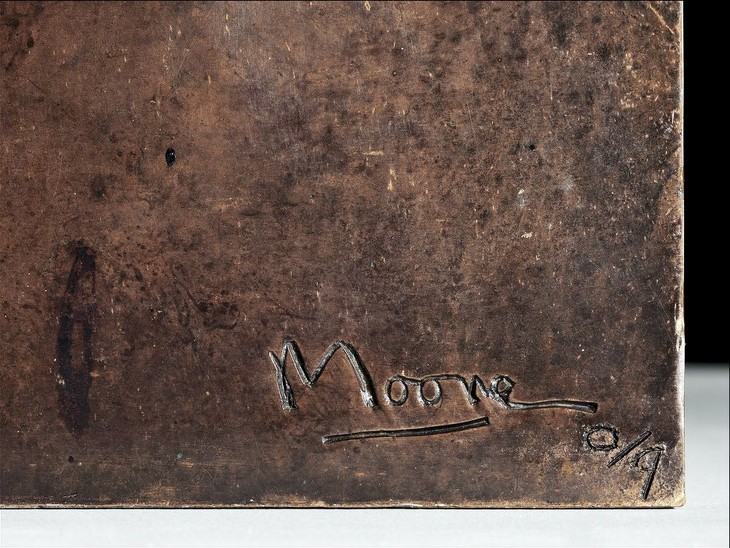

Moon Head 1964 is a bronze sculpture comprised of two thin, irregularly shaped disc-like forms that each stem from an elliptical tubular neck mounted on a bronze base. The two sections of the sculpture are similarly sized and positioned in parallel with each other a few centimetres apart, although they are not aligned directly so that a part of one can always be seen behind the other (fig.1). Seen from each end, it is possible to look through the narrow canyon-like passage between the two pieces (fig.2). From these side views it is evident that each disc has gently undulating surfaces and that each one thins as it tapers towards its upper edge. The way in which the two discs appear to gravitate towards and away from each other at various points gives the impression that the sculpture had, at one time, been a single unit that has been peeled apart.

Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964–6 (side view)

T02297

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964–6 (side view)

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The outer edges of the sculpture are thin, akin to a knife-edge, and feature irregularly shaped gouges that extend towards the centre of each disc. One disc has a large round shape cut from its upper edge (fig.3), while the other disc has an elongated U-shaped notch cut into its lower right edge (fig.4). Although the sculpture was designed to be seen in the round, and has no obvious front or back, Moore did indicate in 1968 that he regarded the disc with the larger incision at its top as ‘the back’.1

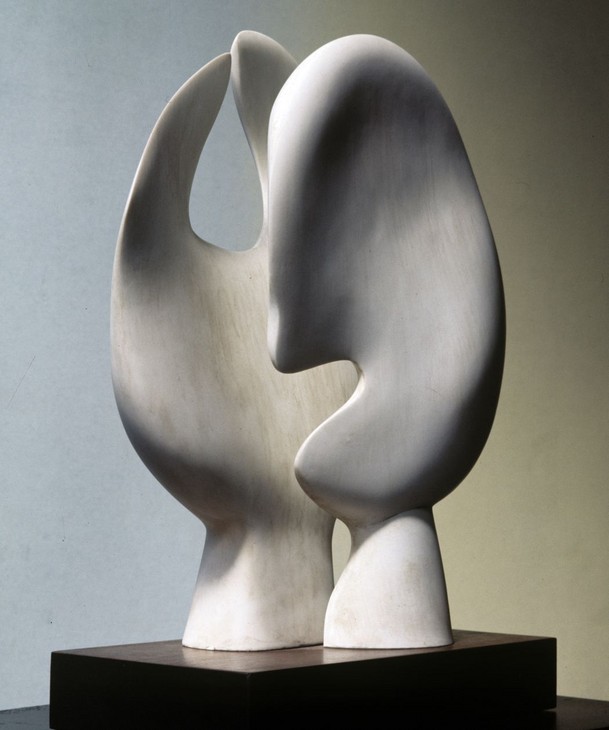

The design of Moon Head is a scaled enlargement of Moore’s Maquette for Head and Hand 1962 (fig.5). Taking its title as a guide, this earlier sculpture can be understood to comprise a head – represented by the disc with the lower horizontal incision, which may denote an open mouth – and a hand – conveyed by the gap in the other disc, which appears to delineate a thumb and forefinger. To create an enlarged bronze version of this sculpture, Moore would have first made a full-size model in plaster, built up over a supportive armature made of wire or wood (fig.6). This work was probably undertaken in his studio at his home, Hoglands, in Perry Green, Hertfordshire. Using an array of tools – including chisels, files and sandpaper – Moore could create different textures according to how wet or dry the plaster was, and these were replicated in the final bronze version. In 1968 Moore explained his preference for plaster when creating a sculpture to be cast in bronze:

I like using plaster as the preliminary material for my bronzes. When people talk about ‘truth to materials’ it doesn’t strictly apply to bronze, because a sculptor does not take a solid piece of bronze and cut it into shape as he does a piece of stone. For a bronze, he first has to make his original in something else. The special quality of bronze is that you can reproduce with it almost any form and any surface texture through expert casting.2

Henry Moore

Maquette for Head and Hand 1962

Bronze

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Maquette for Head and Hand 1962

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Moon Head 1964

Plaster

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Moon Head 1964

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moon Head was cast in an edition nine plus one the artist’s copy at the Noack Foundry in West Berlin, and the sculpture is marked with the foundry’s stamp (fig.7). It is not known for certain whether the whole edition was cast at once or over a period of years. During the 1960s Moore used a number of different foundries depending on the size of the sculpture and how quickly a cast was required. In 1967 Moore stated, ‘I use the Noack foundry for casting most of my work because in my opinion, Noack is the best bronze founder I know ... Also, the Noack foundry is reliable in all ways – in keeping to dates of delivery – and in sustaining the quality of their work’.3 This sculpture was probably made using the sand casting technique, although the finely polished surfaces provide little definitive evidence of the casting methods used.

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on base of Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964–6

Tate T02297

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on base of Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964–6

Tate T02297

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of patina on Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964–6

Tate T02297

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Detail of patina on Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964–6

Tate T02297

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

It is notable that Tate’s example of Moon Head has a very different patina to that usually described in relation to this work. Discussing Moon Head in 1968 Moore stated:

The small version of this piece was originally called ‘Head in Hand’, the hand being the piece at the back. When I came to make it in full size, about eighteen inches high, I gave it a pale gold patina [fig.10] so that each piece reflected a strange, almost ghostly, light at the other. This happened quite by accident. It was because the whole effect reminded me so strongly of the light and shape of the full moon that I have since called it ‘Moon Head’.5

Since Tate’s example was originally the artist’s copy, it can be reasonably assumed that Moore was satisfied with its patina, and that it was not his intention to colour every cast in the edition in the same way.6 Nevertheless, the reproduction of the example with the golden finish in major publications such as Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work (1965) by the critic Herbert Read, and the widespread citation of his 1968 statement about Moon Head,have informed subsequent critical discussions of the sculpture.7

Henry Moore

Moon Head 1964 (with golden patina)

Bronze

578 x 442 x 255 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Henry Moore

Moon Head 1964 (with golden patina)

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Moon Head 1964

Porcelain

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Moon Head 1964

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Another example of Moon Head is held in the Singapore Art Museum (donated by the Sarah Lee Corporation). The remaining casts are believed to be in private collections. The original full-size plaster version is held in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, while the Henry Moore Foundation owns a porcelain version of Moon Head, which was cast in an edition of six plus one artist’s copy in 1964 (fig.11).

Affinities and influences

In 1968 the curator and critic David Sylvester identified Moon Head as belonging to a group of sculptures made by Moore in the early 1960s that demonstrated a preoccupation with thin, flat, sharp-edged forms.8 Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962 (Tate T00603; fig.12), for example, comprises two thin, loosely rectangular forms positioned in parallel with one another, which, according to Moore, have ‘a kind of sliding relationship, like two sliding doors’.9 In this earlier work Moore was particularly interested in exploring the formal relationship between thinness and broadness, believing that ‘sculpture has some disadvantages compared with painting, but it can have one great advantage over painting – that it can be looked at from all round; and if this attitude is used and fully exploited then it can give to sculpture a continual, changing, never-ending surprise and interest’.10 The two-part design of Moon Head and the interstitial space established between the two thin forms (fig.13) bear comparison with Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece. In the same way that the two forms of the earlier sculpture appear to slide past each other when viewed in the round, Sylvester noted that ‘the highly polished bronze’ of Moon Head ‘gives rise, as one looks from the side through the gap between the discs, to a rippling effect in the facing inner surfaces, a ripple as of water which makes the blades seem altogether fluid, so that one feels that here too one is invited to penetrate the space’.11

Henry Moore

Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963

Tate T00603

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.12

Henry Moore

Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963

Tate T00603

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964–6

Tate T02297

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.13

Henry Moore

Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964–6

Tate T02297

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Although he never admitted to being influenced by the work of his contemporary Barbara Hepworth, Moore’s decision to place the two component parts of Moon Head in parallel with one another is, according to the curator Alan Wilkinson, reminiscent of Hepworth’s Disks in Echelon 1935 (Tate T03132; fig.14).12 In this sculpture, which was originally carved in wood, Hepworth positioned two vertically orientated discs ‘in echelon’, a term that refers to two parallel components where one is in advance of the other. Hepworth’s presentation of sculptural forms in echelon became a recurring compositional motif in her work, and Moore would certainly have been familiar with it.

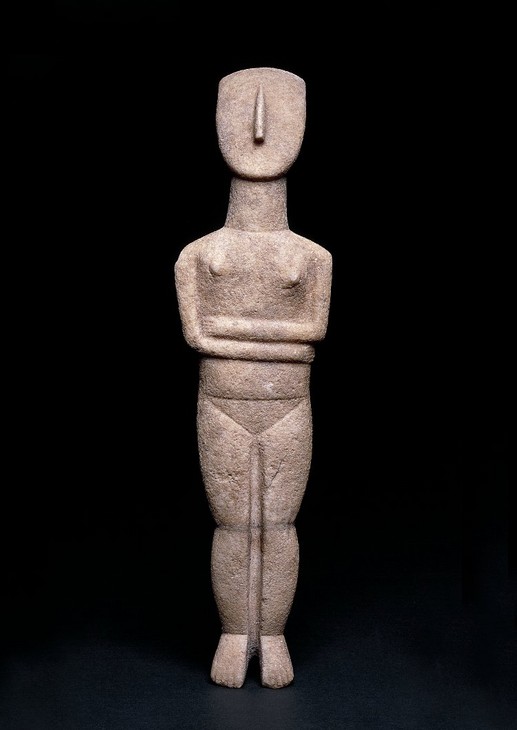

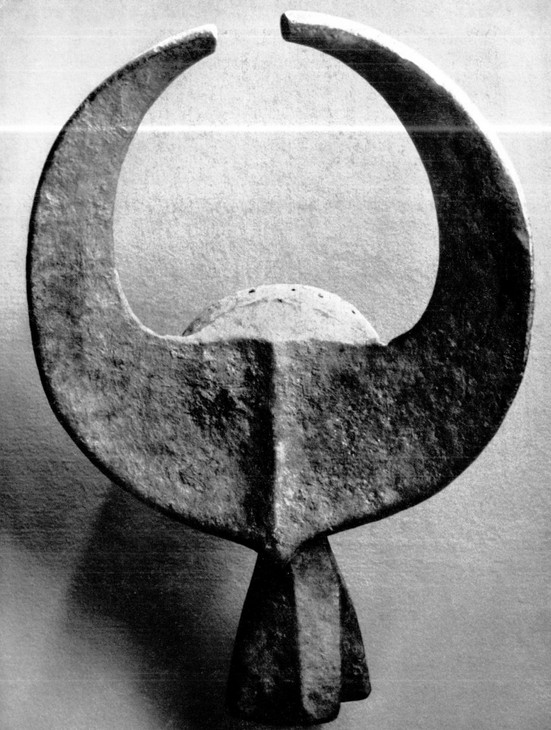

Despite the clear formal affinities between his work and Hepworth’s, Moore chose to highlight the influence of natural materials and ancient Cycladic art in discussions of Moon Head. In 1969 he wrote:

The white [porcelain] two-form sculpture I call ‘Moon Head’ is one of several recent Knife-Edge sculptures I’ve made which have all come about through my interest in bone forms – for example the breast bones of birds – so light, so delicate + yet so strong – But I can also think that my Knife-Edge sculptures may be unconsciously influenced by my liking for the sharp-edged Cycladic idols [fig.15].13

Moore first encountered examples of Cycladic figurines in the British Museum while he was a student in London in the 1920s. His reflections on Moon Head were made in a letter dated June 1969, written to Lord Eccles, Chairman of the Trustees of the British Museum, in response to an invitation to exhibit examples of his work alongside the museum’s collection of ancient Cycladic carvings. Moore’s early interest in Cycladic art may be aligned with the broader artistic tendency known as ‘primitivism’. This over-arching term is used by art historians to describe a propensity of early twentieth-century European modern art to emulate the forms and perceived values of non-Western art, as well as prehistoric and medieval European art. Moore’s interest in so-called ‘primitive’ art dated from his time as a student at Leeds School of Art, where, in 1920, he read the art critic Roger Fry’s influential book Vision and Design (1920), which included chapters on African, Islamic and ancient American arts. In 1947 Moore recalled that ‘Fry opened the way to other books and to the realisation of the British Museum. That was the beginning really ... One room after another in the British Museum took my enthusiasm’.14 Moore admired the ancient marble figurines for their simplified bodily forms and for their emotive power, remarking to Eccles: ‘I love + admire Cycladic sculpture. It has such great elemental simplicity ... The Cycladic marble vases are remarkable inventions, seen just as sculpture in themselves – + the thinness, looked at from the side, of the standing idol figures, adds to their incredible sensitivity.’15

In October 1969 a porcelain version of Moon Head was exhibited in the newly opened Greek and Roman galleries in the British Museum. In an editorial published in the journal Apollo, the critic Denys Sutton applauded the museum’s new display but cautioned that:

exercises of this nature should be undertaken with discrimination ... It is for this reason all the more surprising to find that the new galleries contain one modern work – Moon head by Henry Moore. Few would dispute that Mr. Moore is a leading contemporary sculptor, but whether it was sensible to represent him (and him alone) in these galleries is another and a debatable question.

The idea behind the inclusion of this piece is that the public will be made more receptive to ancient art if it is shown in relationship with that of our period; but it is pretty futile to do this with a work which, if anything, seems closer to Negro than to Cycladic art. In any event it is a shallow theory, for Classical art must be enjoyed on its own terms.16

The idea behind the inclusion of this piece is that the public will be made more receptive to ancient art if it is shown in relationship with that of our period; but it is pretty futile to do this with a work which, if anything, seems closer to Negro than to Cycladic art. In any event it is a shallow theory, for Classical art must be enjoyed on its own terms.16

Undated mask of a Buffalo from northern Nigeria

Nigerian Museum, Lagos

Fig.16

Undated mask of a Buffalo from northern Nigeria

Nigerian Museum, Lagos

The Henry Moore Gift

Installation view of The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, 1978

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.17

Installation view of The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, 1978

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Alice Correia

March 2014

Notes

Richard Wentworth, ‘The Going Concern: Working For Moore’, Burlington Magazine, vol.130, no.1029, December 1988, p.927.

Shortly after Tate had taken receipt of the works that made up the Henry Moore Gift, a number of the sculptures were returned to the artist so that he could adjust the patina, but Moon Head was not one of these.

Henry Moore, letter to Dennis Farr, 15 October 1963, Tate Artist Catalogue File, Henry Moore, A23945.

Alan Wilkinson, ‘Moon Head’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, p.279.

Henry Moore, letter to Lord Eccles, June 1969, reprinted in Henry Moore at the British Museum, London 1981, p.13.

Henry Moore cited in James Johnson Sweeney, ‘Henry Moore’, Partisan Review, March–April 1947, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations,Aldershot 2002, pp.44–5.

Related essays

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- Henry Moore and World Sculpture Dawn Ades

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- Henry Moore and the Values of Business Alex J. Taylor

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

Photograph

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Moon Head 1964, cast c.1964–6 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, March 2014, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www