Henry Moore OM, CH Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown

Image 1 of 10

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Helmet Head and Shoulders

1952, cast date unknown

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

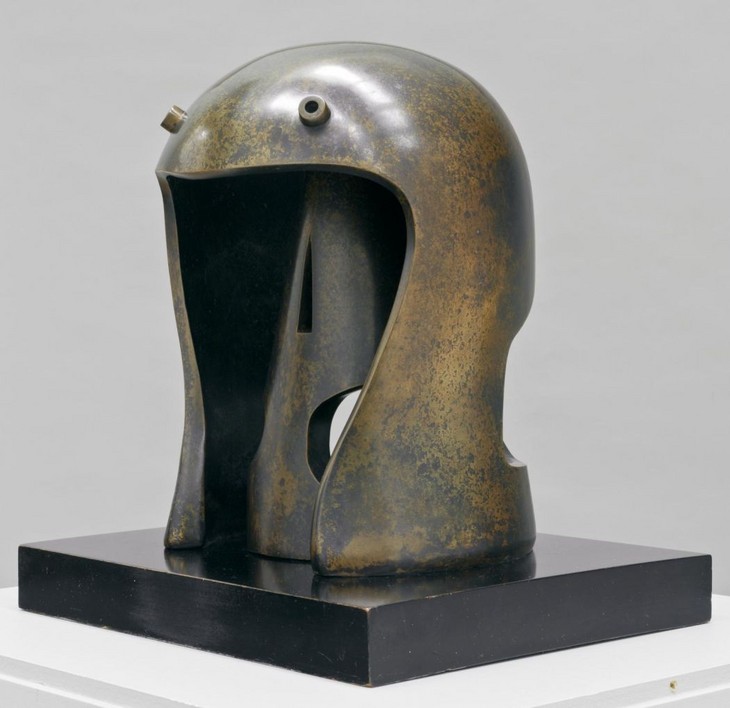

In the early 1950s Henry Moore returned to the subject of the helmet head, which had preoccupied him prior to the Second World War. The militaristic connotations of this theme are exemplified by Helmet Head and Shoulders, which resembles a section of armoury. In addition to the war, sources for this work may be found in Moore’s interest in ancient Greek mythology and metalwork.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Helmet Head and Shoulders

1952, cast date unknown

Bronze

190 x 205 x 150 mm

Presented by the artist 1978

In an edition of 10 plus 2 artist’s copies

T02273

Helmet Head and Shoulders

1952, cast date unknown

Bronze

190 x 205 x 150 mm

Presented by the artist 1978

In an edition of 10 plus 2 artist’s copies

T02273

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1960–1

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, November 1960–January 1961, no.15.

1962

Henry Moore: Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, October–November 1962, no.15.

1963

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings, Ferens Art Gallery, Kingston upon Hull, October–November 1963, no.11.

1968

Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1968, no.76.

1969

Henry Moore, Heslington Hall, York, March 1969, no.6.

1972

Small Bronzes and Drawings by Henry Moore, Lefevre Gallery, London, November–December 1972, no.22.

1975

Henry Moore: Fem Decennier, Skulptur, Teckning, Grafik 1923–1975, British Council touring exhibition: Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter, Oslo, June–July 1975; Kulturhuset, Stockholm, August–October 1975; Nordjyllands Kunstmuseum, Aalborg, October–November 1975, no.40.

1976

The Work of the British Sculptor Henry Moore, Zürcher Forum, Zürich, June–August 1976, no.40.

1978

Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, Cartwright Hall, Bradford, April–June 1978, no.78.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1983

Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, May–September 1983, no number.

1998

Special Exhibitions: Henry Moore, Imperial War Museum, London, September–November 1998.

2007

Moore and Mythology, Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green, April–September 2007, no.90.

2013–14

Bacon / Moore: Flesh and Bone, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, September 2013–January 2014, no.25.

References

1954

New Bronzes by Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Leicester Galleries, London 1954.

1954

Anon., ‘Mr Moore’s New Bronzes: An Experimental Phase’, Times, 15 February 1954, p.4.

1960

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1960, reproduced no.15.

1962

Henry Moore: Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings, exhibition catalogue, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 1962, reproduced no.21.

1965

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 2: Sculpture and Drawings 1949–1955, 1955, 2nd edn, London 1965, p.16 (?another cast reproduced pl.33).

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of His Life and Work, London 1965, p.177 (?another cast reproduced pl.159).

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, p.118, reproduced pl.115.

1972

Small Bronzes and Drawings by Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Lefevre Gallery, London 1972, reproduced no.22.

1975

Henry Moore: Fem Decennier, Skulptur, Teckning, Grafik 1923–1975, exhibition catalogue, Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter, Oslo 1975 (another cast reproduced no.40).

1975

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1975, p.138–42 (?another cast reproduced pl.67).

1976

Henry Moore: Bronzes and Drawings, exhibition catalogue, Fischer Fine Art, London 1976 (?another cast reproduced no.4).

1977

Henry Moore: Sculptures et Dessins, exhibition catalogue, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris 1977 (?another cast reproduced no.65).

1978

Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Cartwright Hall, Bradford 1978, reproduced no.78.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.28.

1981

Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings, Graphics 1921–1981, exhibition catalogue, Palacio de Velázquez, Madrid 1981 (another cast reproduced p.112).

1982

Henry Moore: Head-Helmet, exhibition catalogue, DLI Museum and Arts Centre, Durham 1982, reproduced p.20.

1982

Henry Moore en México: Escultura, Dibujo, Grafica de 1921 a 1982, exhibition catalogue, Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City 1982 (another cast reproduced p.62).

1983

Henry Moore: Esculturas, Dibujos, Grabados – Obras de 1921 a 1982, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Contemporary Art, Caracas 1983, reproduced p.68.

1983

William S. Lieberman, Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1983, reproduced p.70.

1993

Henry Moore: Disegni, Sculture, Grafica, exhibition catalogue, Galleria Pieter Coray, Lugano 1993 (another cast reproduced p.60).

2007

David Mitchinson (ed.), Moore and Mythology, exhibition catalogue, Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green 2007, reproduced p.28.

2010

Gregor Muir (ed.), Henry Moore: Ideas for Sculpture, exhibition catalogue, Hauser & Wirth, London 2010, p.140 (another cast reproduced p.141).

Technique and condition

To cast Helmet Head and Shoulders in bronze Moore would have first executed his design in plasticine. Fragments of the original plasticine model still survive at the Henry Moore Foundation (fig.1). The bronze was cast by the Art Bronze Foundry in London. It is likely that they used the traditional lost wax casting technique, pouring molten bronze into a mould taken from the original model. The outer surface of the bronze provides little indication of the modelling techniques used by Moore; it has been polished to a smooth finish and any marks left by tools are no longer visible. After casting it is likely that the bronze was abraded to remove marks from the outer surface.

Fragments of plasticine model of Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

Fig.1

Fragments of plasticine model of Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

Detail of interior of Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown

Tate T02273

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of interior of Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown

Tate T02273

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

However, marks on the interior, in particular towards the top of the sculpture, suggest that these surfaces received no further treatment after casting and thus retain the surface impressions of the modelled plasticine (fig.2). The sculpture’s interior surfaces also bear a number of regular striations, suggesting the use of a rotary wire brush finisher, along with marks made by hand filing tools on the upper edges of the shoulders, possibly to remove casting flashes or mould lines.

The incised lines that roughly follow the contours of the surface on the sculpture’s right-hand side and at the back of the neck appear to have been made by a hand tool after casting (fig.3). Close examination of these marks shows that they were executed in a series of small arcs rather than in one single stroke. There are no inscriptions or foundry marks on the bronze.

Detail of incised lines on neck of Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown

Tate T02273

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of incised lines on neck of Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown

Tate T02273

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of patina on Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown

Tate T02273

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of patina on Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown

Tate T02273

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The bronze has been artificially patinated with a chemical solution to produce a very dark brown patina (fig.4). On the outside of the sculpture this has been rubbed back to reveal the metal surface, largely confining the dark colour to the interior and crevices. The dark brown patina is slightly mottled and patchy, which may be the result of a concentrated patination solution being stippled onto the surface with a brush, possibly while the bronze was being heated with a blowtorch. Another pale brown, transparent layer of patina appears to have been applied over this before the entire surface received a coating of clear wax.

There are two threaded rods of bronze protruding into the interior of the head. These are usually inserted to repair a fault in the bronze cast or to fill a hole left by the removal of a core pin. The outer surface has been carefully smoothed and patinated so that they are almost invisible to the viewer.

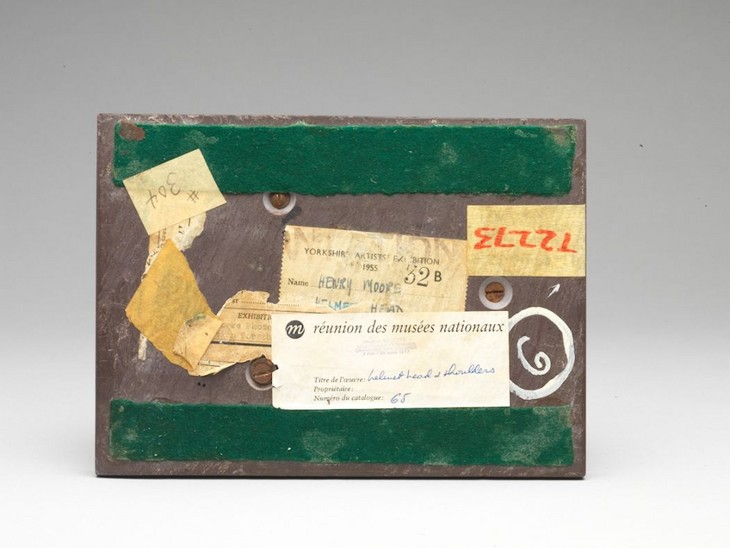

The sculpture has been fixed with screws to a rectangular purple slate base at three points. The visible surfaces of the base have been smoothly polished. It is not known whether this base was selected by the artist but there are exhibition labels on the underneath dating from as early as 1955 and the fixings appear to be original (fig.5).

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2011

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2011, in Alice Correia, ‘Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, October 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Helmet Head and Shoulders is a hollow sculpture consisting of a single, thin piece of curvaceous bronze that delineates the shape of a human head and shoulders. The combination of a smoothed, highly polished exterior surface and a hollow interior is more suggestive of a suit of armour than a human figure, while the toothed helmet conveys a sense of menace and aggression.

The highest point of the sculpture has been modelled into a hollow dome, the surface of which features two small circular holes near the front, in between which a thin straight ridge runs down from the apex of the dome to the lip of the base (fig.1). At the front of the sculpture, directly below this lip, are two differently sized but equally prominent triangular protrusions that point down sharply towards the base. A circular hole marks the central point at which the inner edges of these two triangles meet, behind which the base of the dome curves down and into an almost tubular vertical shaft, reminiscent of a neck. The front half of this shaft is open-ended, revealing it and the dome above to be hollow.

Henry Moore

Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown (rear view)

Tate T02273

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown (rear view)

Tate T02273

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown (front view)

Tate T02273

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown (front view)

Tate T02273

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The tubular form curves outwards from the neck to form what appear to be gently rounded, albeit asymmetrical shoulders. When seen from the rear, the back of the sculpture forms an arch so that the left flank rests on the base at a single point (fig.2). From this angle a set of three arced striations can also be seen radiating from the rounded lower edge of the dome to around the point where the neck begins to curve outwards. Similar contour lines feature around the rounded left shoulder, although here the striations are deeper and thus more prominent. The edge of the left shoulder extends downwards to the base before curling upwards and across the front, perhaps echoing the position and shape of a breastplate (fig.3). Here it is cut off by a straight vertical edge, continued downwards from the open neck. In contrast, the other edge of the open neck leads down the top edge of the right shoulder, curling smoothly down and around towards the base, culminating in a point near the centre. As a result the cavity on this side of the sculpture is left exposed with no comparable breastplate closing it off.

Detail of incised lines on right flank of Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown (front view)

Tate T02273

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of incised lines on right flank of Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown (front view)

Tate T02273

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown (side view)

Tate T02273

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown (side view)

Tate T02273

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

While the left shoulder and breastplate are marked by striations that radiate downwards at increasing intervals from the neck, only the upper edge of the right flank features comparable but smaller incised lines (fig.4). On this side the open cavity exposes the inner surface of the sculpture, which is revealed to be rougher and duller than the smooth and polished exterior. This surface is also slightly pitted and bears a multitude of evenly-spaced scratches produced by a rotary wire brush. The sculpture rests on the base at the tip of the left flank and at two points on the right, at the back and at the front, separated by a shallow arch (fig.5).

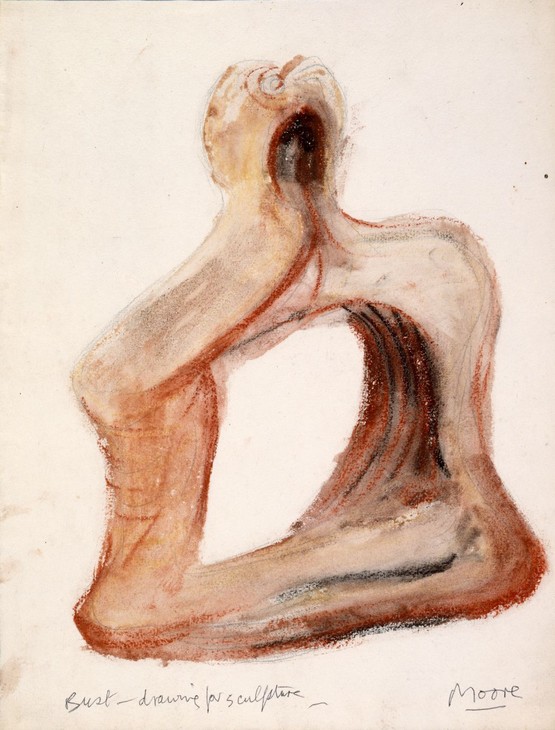

Making the sculpture

Henry Moore

Bust: Drawing for Sculpture c.1950

Graphite, pastel, wash on paper

304 x 233 mm

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Bust: Drawing for Sculpture c.1950

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

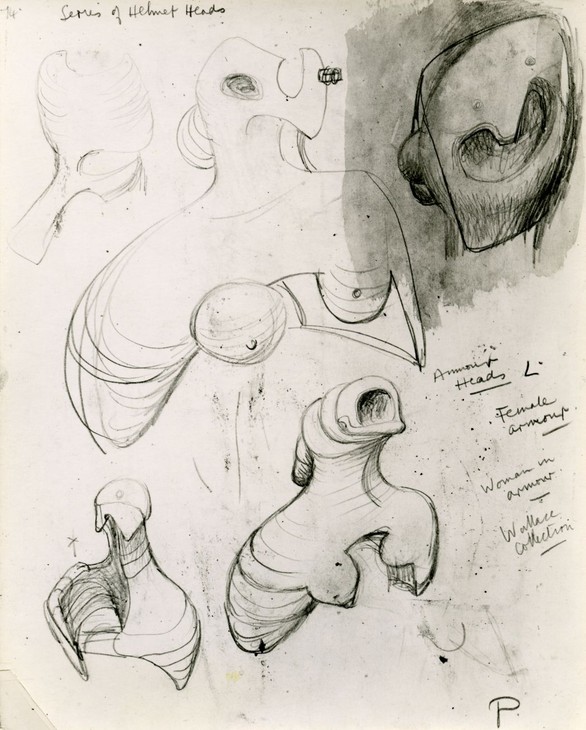

Henry Moore

Series of Helmet Heads c.1950–1

Graphite, wash on paper

290 x 235 mm

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.7

Henry Moore

Series of Helmet Heads c.1950–1

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore annotated his initial sketches with the phrases ‘Armour Heads; Female Armour; Woman in Armour; Wallace Collection’. Discussing his Helmet Head series in 1980 Moore recalled that ‘the idea of one form inside another form may owe some of its incipient beginnings to my interest at one stage when I discovered armour. I spent many hours in the Wallace Collection, in London, looking at armour’.2 When he visited the Wallace Collection as a student in the 1920s Moore would have had access to one of the largest collections of armoury in Britain, including items dating back to the fourteenth century. Moore’s study of armoury not only prompted him to depict armoured structures but also to reinterpret the representation of the body. According to the critic John Russell this was particularly evident in the ‘woman in armour’ drawing, where ‘it is hard to tell where the breastplate ends and the naked human breast takes over’.3

In order to transform his pencil design into a bronze sculpture Moore first needed to create a three-dimensional model. He did this using plasticine, a malleable material which Moore preferred to clay because it did not dry out and harden as quickly. Fragments survive of the original plasticine model for Helmet Head and Shoulders, which are held in the collection of the Henry Moore Foundation (fig.8).

Fragments of plasticine model of Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

Fig.8

Fragments of plasticine model of Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

Detail of interior of Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown

Tate T02273

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Detail of interior of Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown

Tate T02273

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Although the smooth exterior of Tate’s sculpture does not show any trace of Moore’s modelling techniques, the interior of the helmet does reveal the texture of the plasticine (fig.9). Once Moore was satisfied with the surface finish of the sculpture and was sure that he wanted to proceed with the casting process, it would have been sent to a professional foundry to be cast in bronze. Although Helmet Head and Shoulders is not stamped with a foundry mark, records held at the Henry Moore Foundation note that the sculpture was cast at the Art Bronze Foundry in London, which Moore had previously employed to cast his maquettes for Madonna and Child in 1943 (see Tate N05600). It is likely that Moore first came into contact with the foundry when he was Head of the Sculpture Department at Chelsea College of Art in the 1930s because it was located close to the college and was used regularly by staff and students.

The bronze sculpture was most likely created using the lost wax casting technique, which would have first involved the manufacture of a mould of the original model, into which molten wax would be poured and left to harden to create an exact replica of the original plasticine sculpture. This wax replica would then be encased in a hard refractory material, placed in a kiln and heated. Channels within the casing would allow the melted wax to drain away leaving an empty cavity which could then be filled with molten bronze. In order to achieve an even and flawless cast all of the molten bronze had to be poured in one go. Once the bronze had cooled and hardened, the casing was removed to reveal the finished sculpture.4

After casting at the foundry Helmet Head and Shoulders was probably returned to Moore so that he could inspect its quality and make decisions about the patination. A patina is the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the pre-heated bronze surface. In 1963 Moore asserted, ‘I always patinate bronze myself’, explaining that since he had designed the sculpture it was unlikely that anyone else would be able to create the exact colour he wanted.5 He went on to explain that ‘one tries with any patina to help the form of a sculpture rather than to obscure it’, and compared a patina with a person’s complexion, suggesting that if a girl ‘has a bad complexion ... you don’t notice how beautiful she may be’.6

Tate’s version of Helmet Head and Shoulders has been patinated a very dark brown, bordering on black (fig.10). The dark patina seen on the external surface has been rubbed back to reveal the natural golden colour of the metal and has a slightly patchy or worn appearance, which may be have been achieved by applying a concentrated patination solution to the bronze while it was heated with a blowtorch. In contrast, the interior surface has a consistently dark patina.

Helmet Head and Shoulders was produced in an edition of ten plus two artist’s casts. It is numbered 304 in the second volume of the artist’s catalogue raisonné, published in 1955.7 Other examples of this sculpture were initially sold to two of Moore’s long-standing supporters: Kenneth Clark, former Director of the National Gallery, London, and Reverend Walter Hussey of St Matthew’s Church in Northampton, who had commissioned Moore’s Madonna and Child for the church in 1942. Hussey’s cast is now held in the collection of Pallant House Gallery, Chichester. Other examples are held in the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Henry Moore Family Collection. The remaining casts are believed to be held in private collections.

Sources and development

In a conversation with Tate researcher Richard Calvocoressi on 12 December 1980, ‘Moore said that the conjunction of sharp points with the helmet form was intended to express the idea of aggression and war, although in this sculpture the shoulders introduce a protective element’.8 This protective dimension is also a feature of a contemporaneous work, Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3 (Tate T02272), which itself developed from Moore’s pre-war investigations into the protective relationship between interior and exterior forms, and the notion of the body as a protective shell.

In 1939 Moore made a number of drawings depicting the motif of the ‘helmet head’. One of these, Drawing for Metal Sculpture: Two Heads 1939 (fig.11), was singled out by the art historian Andrew Causey for revealing Moore’s mindset when he set out to explore the relationship between enveloped and enveloping forms. For Causey, ‘Moore’s hatching and shading create dark corners and uncomfortable spaces’ that convey the widespread anxiety regarding the impending Second World War.9 In 1967 Moore explained that in developing his helmet head series he was interested in ‘the mystery of semiobscurity where one can only half distinguish something. In the helmet you do not quite know what is inside’.10

Henry Moore

Drawing for Metal Sculpture: Two Heads 1939

Charcoal, wash, pen and ink on paper

277 x 381 mm

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Drawing for Metal Sculpture: Two Heads 1939

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

The Helmet 1939–40

Lead

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.12

Henry Moore

The Helmet 1939–40

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore’s first three-dimensional work to take the form of a helmet and combine interior and exterior forms was a lead sculpture titled The Helmet 1939–40 (fig.12). For this work Moore enclosed a form made up of arches and ellipses, which may bear analogy to a standing figure, within a domed shelter. Although the art historian Julian Stallabrass has argued that Moore’s helmet head sculptures ‘have a very definite relation to the war’, this work can also be viewed in light of Moore’s interest in the mother and child motif.11 In 1967 Moore acknowledged that this compositional arrangement related to ‘the Mother and Child where the other form, the mother, is protecting the inner form, the child’.12 Furthermore, the German psychologist Erich Neumann argued in 1959 that in the helmet head sculptures ‘the head itself becomes the sheltering uterus’.13

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960

Tate T00388

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.13

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960

Tate T00388

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Openwork Head and Shoulders 1950

Bronze

455 x 390 x 260 mm

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.14

Henry Moore

Openwork Head and Shoulders 1950

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Although a lack of material resources halted Moore’s sculptural practice during the Second World War, in 1950 he returned once again to the helmet head motif with Helmet Head No.1 1950 (fig.13). However, according to Neumann, when Moore returned to the theme after the war he dispensed with the mother and child symbolism of his pre-war sculpture. Instead, Neumann argued, ‘the motif of the diving helmet, the crash helmet, and the gas mask, all of which convert the human face into something strange and inhuman, has here been wrought into a new and sinister form of death’s-head’.14 Neumann regarded the helmet heads of 1950 as figures from a mechanistic world, in strong contrast to Moore’s figurative sculptures based on organic forms. He suggested that they have a parallel in the ‘Openwork Heads’ of the same year, although in these sculptures a lattice-work shell encloses the interior void (see fig.14). For Neumann, Moore’s ‘Openwork Heads’ presented the head:

only as a mask, a hollow shell derived from the outer layer of skin and muscle. These heads have been, so to speak, peeled off the bone, the density and solidity of the head’s structure are broken down, and all that remains is the outline of the form, with nothing inside save the air filtering in through the openwork.15

Neumann concluded that Moore’s experimentation with latticed, open structures ‘has resulted in a representation of the “nihilistic” man of today, obsessed with the Void, le néant, nothingness’.16

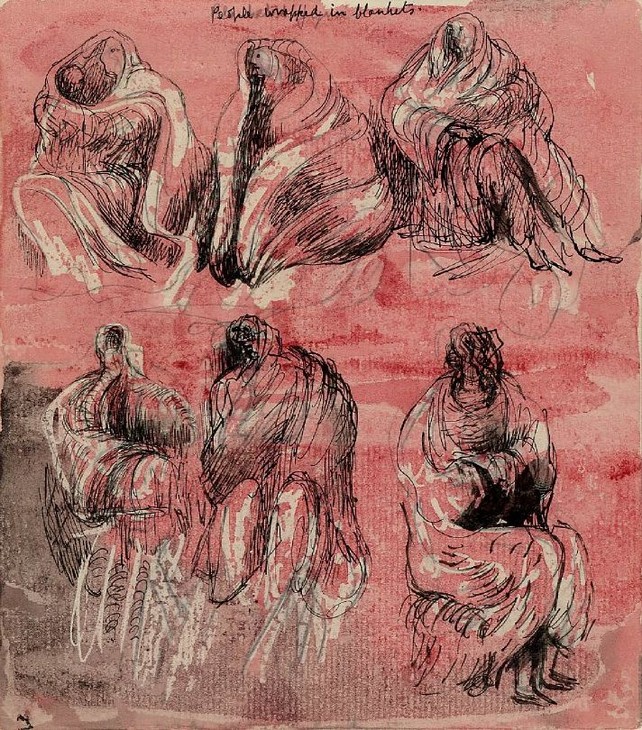

Henry Moore

Six Seated Figures Wrapped in Blankets 1940–1

Pen and black ink, graphite, white wax crayon and watercolour on paper

187 x 165 mm

The British Museum, London

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.15

Henry Moore

Six Seated Figures Wrapped in Blankets 1940–1

The British Museum, London

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

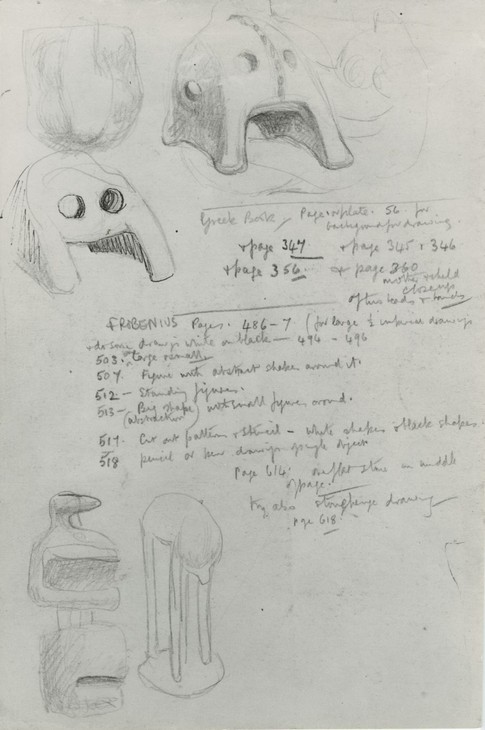

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture and Artist's Notes 1937

Graphite, pen and ink and chalk on paper

272 x 184 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.16

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture and Artist's Notes 1937

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

In addition to his visit to Greece in 1951 and his study of reproductions, Moore was familiar with the collection of ancient Greek art housed in the British Museum. In 1981 he selected a statue of an armed rider for publication in the book Henry Moore at the British Museum, in which objects from the museum’s collection that had influenced him during his career were collated. The sculpture, known as the ‘Armento Rider’ (fig.17), depicts a male warrior wearing a Corinthian-style helmet and short tunic, seated upon a horse. Although Moore’s introductory text makes no specific link between his helmet head series and the ‘Armento Rider’, and the statue should not be regarded as a direct source, this object demonstrates the diverse repertoire of forms that were available to Moore as he began to consider the structure of armour as a model for his sculpture.

Exhibition and interpretation

Henry Moore

Pallas Athene Seals c.1954

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.18

Henry Moore

Pallas Athene Seals c.1954

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Carving 1935

Cumberland alabaster

292 x 295 x 171 mm

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.19

Henry Moore

Carving 1935

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

A cast of Helmet Head and Shoulders belonging to Moore’s wife Irina was included in his solo exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, in November 1960. The exhibition comprised sculptures made since 1950 and was Moore’s first major exhibition in London for five years. Writing in the Listener, the critic Keith Sutton noted that the layout and content of the exhibition created ‘the impression that the Whitechapel is, for the present, a noble and sombre anteroom to a great museum packed with treasures. We feel at once that all these works of art are in the mainstream of grand historical art – as we know it from museums’.23 Perhaps aware of Moore’s trip to Greece in 1951 and his ensuing ‘Greek’ phase, Sutton went on to state that ‘the visual association between this exhibition and the Elgin rooms at the British Museum is neither casual nor fortuitous. The allusions to classical forms are explicit in the works’.24 However, for Sutton, Moore’s works ‘make use of art history but do not interrogate it, they make statements rather than queries’.25 Sutton concluded his review by suggesting that Moore’s attempt to create a modern variation of heroic classical art had produced a set of works without any notion of human fallibility or capacity for self-reflection, leaving the artist open to ridicule and parody. Robertson similarly acknowledged the detrimental effects of Moore’s recourse to historical forms in the 1950s, writing in 1963 that ‘There was once a danger that a consciousness of art might stifle his development and his ability to be true to himself’.26

The Henry Moore Gift

Helmet Head and Shoulders was presented by Henry Moore to the Tate Gallery in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift. The Gift comprised thirty-six sculptures in bronze, marble and plaster and was exhibited in its entirety alongside Tate’s existing collection of Moore’s work in an exhibition celebrating the artist’s eightieth birthday, which opened in June 1978. A press release was duly prepared announcing that ‘The group [of sculptures] is the most substantial gift of works ever given to the Tate by an artist during his lifetime’.27 The exhibition was attended by over 20,500 people and nearly 11,000 copies of the catalogue were sold.28 At the close of the exhibition in late August 1978 the Director of Tate Norman Reid reflected in a letter to Moore’s daughter Mary Danowski that although he was sad to see the exhibition come to an end ‘we have the consolation of the splendid group of sculptures which Henry has presented to the nation’.29

Alice Correia

October 2013

Notes

For the sketches made between 1950 and 1951 see Ann Garrould (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 4: Complete Drawings 1950–76, London 2003.

Henry Moore in conversation with David Mitchinson, 1980, extract of transcript reproduced in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.213.

For an explanatory video about the lost wax process see http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/s/sculpture-techniques/ , accessed 17 October 2013.

Henry Moore in ‘Henry Moore Talking to David Sylvester’, 7 June 1963, transcript of Third Programme, broadcast BBC Radio, 14 July 1963, Tate Archive TGA 200816, pp.3–4. (An edited version of this interview was published in the Listener, 29 August 1963, pp.305–7).

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 2: Sculpture and Drawings 1949–1955, 1955, 2nd edn, London 1965, p.16 (?another cast reproduced pl.33).

Richard Calvocoressi, ‘T.2273 Helmet Head and Shoulders’, The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, p.120.

Henry Moore, cited in Michael Chase, ‘Moore on his Methods’, Christian Science Monitor, 24 March 1967, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.214.

Julian Stallabrass, ‘Darkness in the Shelter’, in Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao, Bilbao 1990. See http://www.courtauld.ac.uk/people/stallabrass_julian/PDF/Bilbao.pdf , accessed 22 October 2013.

Alan Wilkinson, The Drawings of Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1977, p.144.

Roger Cardinal, ‘Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece’, in Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece, exhibition catalogue, Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation Museum of Contemporary Art, Andros 2000, p.30.

David Mitchinson (ed.), Moore and Mythology, exhibition catalogue, Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green 2007, p.10.

T.W. Earp, ‘Henry Moore’s Coat of Many Colours’, Daily Telegraph, 12 February 1954, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Related essays

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related material

Related reviews and articles

- Keith Sutton, ‘Henry Moore at Whitechapel’ Listener, December 8 1960.

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Helmet Head and Shoulders 1952, cast date unknown by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, October 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www