Henry Moore and World Sculpture

Dawn Ades

In 1926 Moore wrote in a note to himself ‘Keep ever prominent the world tradition | the big view of sculpture’. This essay explores what this phrase would have meant to him, and, in particular, the context of his deep admiration for Mexican sculpture.

In 1961 the Sunday Times published two conversations between Henry Moore and John and Vera Russell, in which they discussed the problem of ‘beauty’ in modern art. They addressed the question in general, and Moore then turned it particularly to sculpture. The great advances in modern sculpture, Moore said, had nothing to do with what conventionally passes as beautiful – copies of something beautiful in nature, or something craftsmanlike and nicely finished in a ‘beautiful’ material like white marble or alabaster. In modern sculpture the real discoveries, in Moore’s opinion, had been quite various, including the stripped simplicity of the streamlined sculptures of Brancusi and the use of readymade and found objects, but, above all, it was sculpture from ‘the whole history of mankind’, including so-called ‘primitive art’, that had opened the artist’s eyes to new forms. When Moore said this he meant it both historically and geographically.1 The deep significance of African sculpture for the pre-First World War generation of modern artists was well known. In his conversations with the Russells, he commented, ‘The new friendship ... between art and anthropology has been of fundamental importance to twentieth-century art. We know that Epstein and Derain and Picasso and Braque were influenced before 1914 by the Negro sculptures which are now in the Musée de l’homme in Paris, and anyone who knows that museum and knows modern art can find evidence as he goes round that some artist has been round before him.’2

In talking about art and anthropology Moore was reflecting the reality of the situation in which objects from non-Western cultures were amassed in the old Musée de l’homme in Paris and other so-called ‘museums of mankind’, and classified in various ways (according to place, tribe, use, etc.), none of them to do with art. Spears, paddles, masks, carvings of people and animals were all shown together without any regard for aesthetics. It was such artists as Jacob Epstein, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and Pablo Picasso, who recognised qualities in African, or in Oceanic, sculptures that spoke to their need to revitalise western traditions. Carl Einstein, having visited Paris before the war and met Picasso, wrote an influential study of African sculpture, Negerplastik (1915), which addressed the subject from a purely aesthetic standpoint. ‘The art object is real because it is closed form. Since it is self-contained and extremely powerful, the sense of distance between it and the viewer will necessarily produce an art of enormous intensity.’3 Moore knew Einstein’s book, which informed his notes on ‘Negro Sculpture’ (c.1925–6): ‘The Negroes ... undoubtedly possessed high sculptural genius. Their carvings show them to have had a wonderfully fertile invention of abstract forms.’4 At the end of the essay he noted the illustrations ‘in the Negro book’ that he found most satisfying – a reference to Negerplastik. Guillaume Apollinaire, poet, critic, champion of cubism and friend of Picasso, wrote an introduction to Sculptures nègres (1917), a volume of plates published by the dealer Paul Guillaume that brought together ‘a series of typical examples from an aesthetic point of view.’5 It was, Apollinaire wrote, ‘only by an audacious leap of taste that we have come to consider these negro idols as true works of art’.6 Apollinaire’s text is interesting as it highlights one of the central issues that still affects attitudes to African and Oceanic sculpture: if it is to be understood as art, on what, or whose, terms? Curiously avoiding mention of Mexican or Central American art, Apollinaire wrote:

For some years artists, art lovers and museums have taken an interest in the idols of Africa and Oceania, from a purely artistic point of view, abstracting from the supernatural character attributed to them by the artists who sculpted them and the believers who paid homage to them. But no critical apparatus is at the disposition of this new curiosity, and a collection of negro statues cannot be presented in the same way as a collection of art objects, paintings or statues made in Europe, in Asian countries with a classical civilisation, in Egypt and other roman regions of North Africa.7

A significant problem was that neither anthropology nor aesthetics had the tools to begin to understand and order the objects, as the kinds of information typically used for art in European museums (date, name of artist, school, etc.) was lacking. Not a single name of an artist, Apollinaire remarked, was as yet known. This did not bother the artists who looked and took what they wanted from the treasure of unfamiliar forms but Western commentators, facing cultural difference, were embroiled in arguments which typically sought to oppose ‘civilised’ to ‘primitive’ – a term that has long haunted critics, historians and anthropologists.

Moore’s use of ‘anthropology’, in his conversation with the Russells, could be seen as a euphemism for ‘primitive’. Although forms of primitivism have been present since antiquity, the new disciplines of anthropology and ethnology began in the latter part of the nineteenth century to define ‘primitive’ or ‘tribal’ societies in Darwinian terms of evolution, usually in opposition to Western ‘civilisation’. One of the most influential ethnologists, Lucien Lévy-Bruhl, for example, argued that tribal peoples lived in a primitive state, with a mentality different in kind from civilised peoples. Les Functions mentales dans les sociétés inférieures (1910) was translated into English as How Natives Think in 1926. Commonly primitive peoples were compared to children or Stone Age ancestors, but unchanged by the passage of time. The French anthropologist Lévi-Strauss did not view primitive societies as inferior, but still, as in La Pensée sauvage (1962), as different, remote from Western ideas of progress and, in a way, outside of time.8 For a long time very little attempt was made to research the kind of information, such as dates and modes of production and names of artists, whose absence Apollinaire had regretted, and which seemed to him to divorce African and Oceanic art from ‘Art’. Moore himself said in a 1941 essay:

The term ‘Primitive Art’ is generally used to include the products of a great variety of races and periods in history, many different social and religious systems. In its widest sense it seems to cover most of those cultures which are outside European and the great Oriental civilizations. This is the sense in which I shall use it here, though I do not much like the application of the word ‘primitive’ to art’.9

‘Viewed as the material culture of long-standing traditions, primitive art [was] thus cast as static and isolated from history’, summarised Colin Rowe in his 1994 study of primitivism and modern art.10 Without denying the unavoidable and virtually unconscious colonialist and even racist attitudes of the time, however, there was, as the artist Susan Hiller noted in 2003, a positive and optimistic register to the different ‘discoveries’ made by artists like Picasso, Moore, Epstein, Brancusi, Giacometti and so on, for they also marked the dissolution of cultural boundaries and acceleration of cultural influences, and prefigured and enabled the ‘increasing hybridisation of Western culture’.11

Moore developed a view of world sculpture in which the Western, essentially Greco-Roman, tradition took a marginal role. A significant early discovery was Roger Fry’s essay on ‘Negro Sculpture’ in Vision and Design (1920), which, Moore said, ‘stressed the ‘three-dimensional realisation’ that characterised African art and its ‘truth to material’. Fry also wrote that modern artists had started to look to Aztec and Maya sculpture for inspiration, one result ‘of the general aesthetic awakening which has followed on the revolt against the tyranny of the Graeco-Roman tradition.’12 Moore was responding here to the ideas of not only Fry but also a number of sculptors working in Britain before the first World War, above all Epstein and Gaudier-Brzeska, who championed a new and inclusive approach to sculpture all over the world. In his 1914 Vortex manifesto for Wyndham Lewis’s Blast, Gaudier-Brzeska had surveyed sculpture from every time and place, from the Palaeolithic to the contemporary and across the globe. He dismissed Greece: ‘The fair Greek saw himself only ... HIS SCULPTURE WAS DERIVATIVE his feeling for form secondary’ and raced over Europe, Egypt, India, China, Mexico and Africa, analysing these countries’ sculpture from the point of view of form and energy: ‘We the moderns, Epstein, Brancusi, Archipenko, Dunikowski, Modigliani and myself, through the incessant struggle in the complex city, have likewise to spend much energy’.13 For Moore, recognition that the ideal of Greece was not only outdated but peripheral, gave him the sense of rejoining a wider sculptural world: ‘the realistic idea of physical beauty in art which sprang from fifth-century Greece was only a digression from the main world tradition of sculpture, whilst, for instance, our own equally European Romanesque and Early Gothic are in the main line.’14 On a drawing of 1926 he scribbled: ‘Development of sculpture from now/not back to Maillol & archaic Greek/& modelling.’ 15

Moore’s letters and sketchbooks of the 1920s show the development of his keen interest in the sculpture in the Ethnographic Room at the British Museum. On his second visit to the Museum in October 1921, he wrote to a friend that he spent an afternoon with the Egyptian and Assyrian sculptures and then, ‘An hour before closing time I tore myself away from these to do a little exploring and found – in the Ethnographical Gallery – the ecstatically fine negro sculptures’.16 Sketches of wooden African carvings pay close attention to free, abstracted treatment of the figure in the round.17 During the early 1920s he relished the freedom to explore outside the Western tradition, and was familiar with the art of many cultures, but it was above all in the sculpture from Mexico that he found inspiration. His research in the British Museum and in books on Mexican art and his thoughtful interrogation of what he perceived as its special qualities and their relevance for himself carried him onto a parallel track with the surrealists in Paris. In the British Museum the Ethnographical Room, he later recalled, ‘contained an inexhaustible wealth and variety of sculptural achievements (Negro, Oceanic Islands, and North and South America), but overcrowded and jumbled together like junk in a marine stores, so that after hundreds of visits I would still find carvings not discovered there before ... Of works from the Americas, Mexican art was exceptionally well represented.’18 This was a consequence of the English explorers and archaeologists who had brought back their treasures in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries from the major Mesoamerican sites. Moore’s discovery of Mexican sculpture coincided with his first year at the Royal College of Art in 1921. He was already interested in direct carving, championed above all by Epstein, and found Mexican sculpture much closer to his taste and ambitions than the traditional figurative works he was taught in the College to copy. He later explained:

Moore’s letters and sketchbooks of the 1920s show the development of his keen interest in the sculpture in the Ethnographic Room at the British Museum. On his second visit to the Museum in October 1921, he wrote to a friend that he spent an afternoon with the Egyptian and Assyrian sculptures and then, ‘An hour before closing time I tore myself away from these to do a little exploring and found – in the Ethnographical Gallery – the ecstatically fine negro sculptures’.16 Sketches of wooden African carvings pay close attention to free, abstracted treatment of the figure in the round.17 During the early 1920s he relished the freedom to explore outside the Western tradition, and was familiar with the art of many cultures, but it was above all in the sculpture from Mexico that he found inspiration. His research in the British Museum and in books on Mexican art and his thoughtful interrogation of what he perceived as its special qualities and their relevance for himself carried him onto a parallel track with the surrealists in Paris. In the British Museum the Ethnographical Room, he later recalled, ‘contained an inexhaustible wealth and variety of sculptural achievements (Negro, Oceanic Islands, and North and South America), but overcrowded and jumbled together like junk in a marine stores, so that after hundreds of visits I would still find carvings not discovered there before ... Of works from the Americas, Mexican art was exceptionally well represented.’18 This was a consequence of the English explorers and archaeologists who had brought back their treasures in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries from the major Mesoamerican sites. Moore’s discovery of Mexican sculpture coincided with his first year at the Royal College of Art in 1921. He was already interested in direct carving, championed above all by Epstein, and found Mexican sculpture much closer to his taste and ambitions than the traditional figurative works he was taught in the College to copy. He later explained:

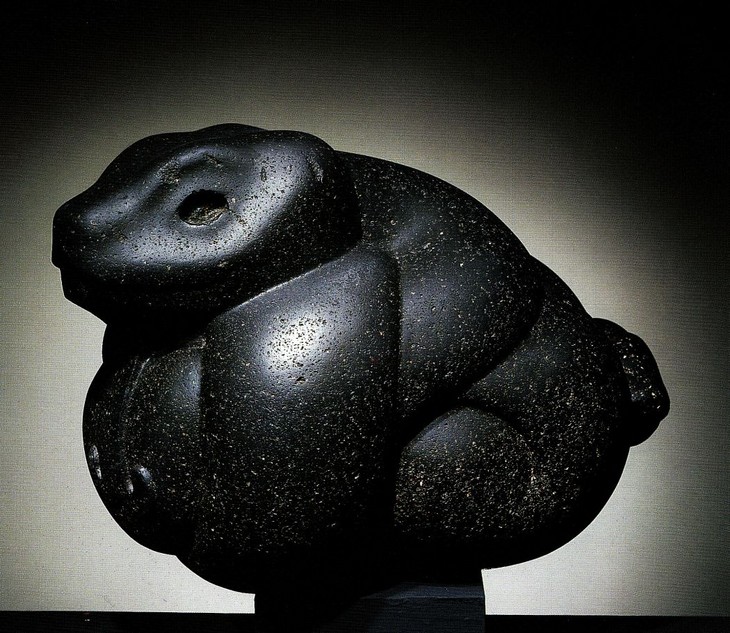

Mexican sculpture, as soon as I found it, seemed to me true and right, perhaps because I at once hit on similarities in it with some eleventh-century carvings I had seen as a boy on Yorkshire churches. Its ‘stoniness’, by which I mean its truth to material, its tremendous power without loss of sensitiveness, its astonishing variety and fertility of form-invention and its approach to a full three-dimensional conception of form, make it unsurpassed in my opinion by any other period of stone sculpture.19

Moore’s fascination with pre-conquest American sculpture dates from the early 1920s, before his awareness of surrealism, but he went on to collect Pre-Columbian art like many of his surrealist comrades, although not on the scale of, for example, the leading poets of the surrealist movement André Breton and Paul Eluard, or the surrealist artist Wolfgang Paalen.

Henry Moore

Mother and Child 1924–5

Manchester City Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Mother and Child 1924–5

Manchester City Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Henry Moore

Snake 1924

Marble

171 x 165 x 127 mm

Collection of Mary Moore

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Snake 1924

Collection of Mary Moore

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Serpent Late post–classic period 1300–1521

Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico

Fig.3

Serpent Late post–classic period 1300–1521

Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico

Henry Moore

Girl with Clasped Hands 1930

British Council Collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Girl with Clasped Hands 1930

British Council Collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

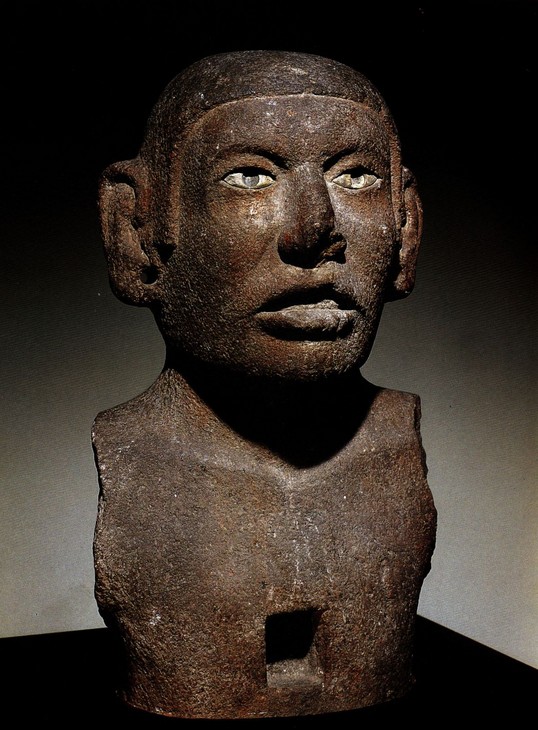

Torso, Late post-classic AD 1300-1521, Mexica culture

Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico

Fig.5

Torso, Late post-classic AD 1300-1521, Mexica culture

Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico

Mexican sculpture played a truly vital role in Moore’s early career. In 1947 he recalled:

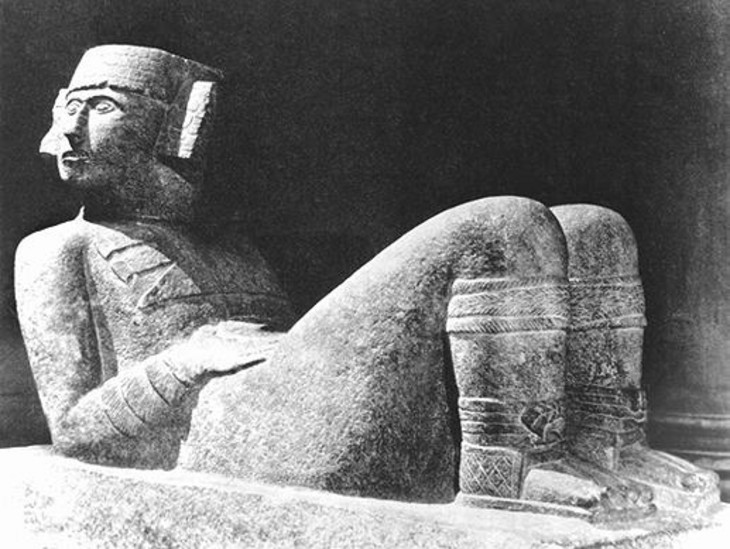

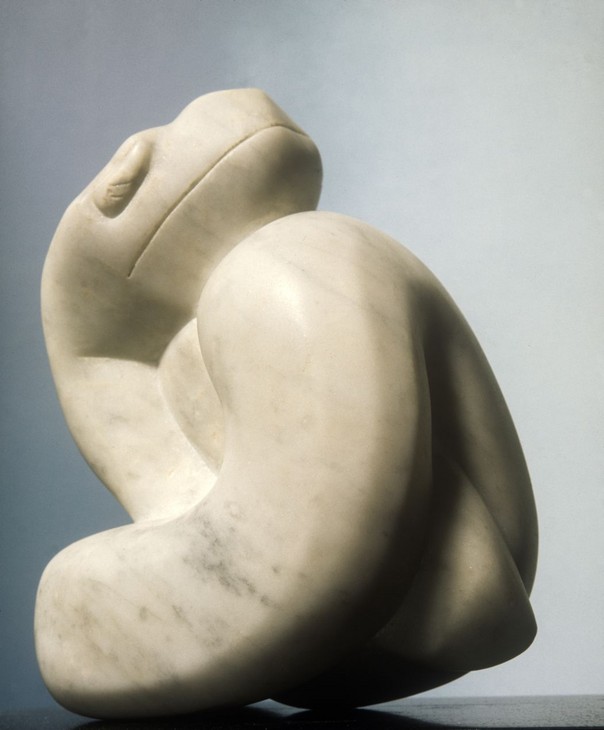

For six months after my return [from Italy in 1924] I was never more miserable in my life. Six months exposure to the master works of European art which I saw on my trip had stirred up a violent conflict with my previous ideals ... I found myself helpless and unable to work. Then gradually I began to find my way out of my quandary in the direction of my earlier interests. I came back to ancient Mexican art at the British Museum. I came across an illustration of the Chacmool discovered at Chichen Itza in a German publication – and its curious reclining posture attracted me – not lying on its side, but on its back with its head twisted around.21

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1929

Brown Hornton stone

Leeds City Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1929

Leeds City Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

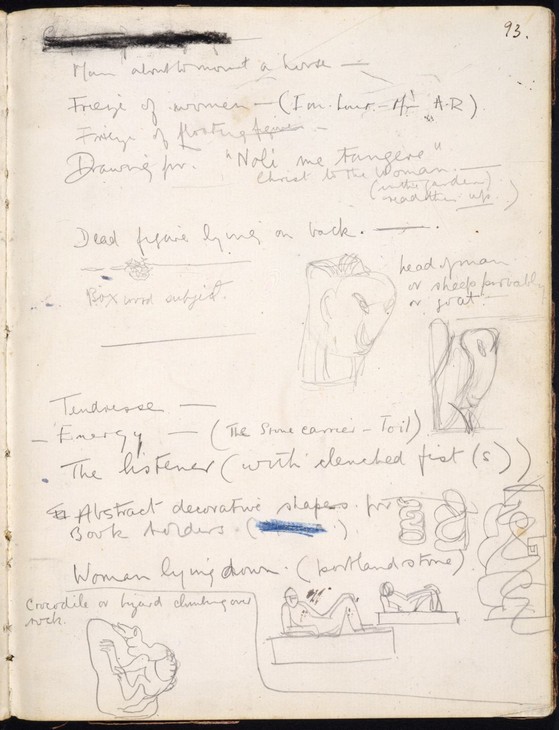

Henry Moore

Studies for Sculpture Notebook no.2 c.1921–2

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.7

Henry Moore

Studies for Sculpture Notebook no.2 c.1921–2

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

The chacmool was fundamental to one of Moore’s recurrent themes, the reclining figure, and makes its imposing presence clear in the 1929 Reclining Figure 1929 (fig.6). The exact date of his ‘discovery’ is unclear, because as early as 1922 he made two tiny sketches of a reclining figure on a rectangular base which undoubtedly suggest a chacmool, a generic stone carved figure on a rectangular base that typically was positioned at the entrance to a temple (fig.7). But perhaps it had not hitherto made the impact on him that was produced by the stark contrast with the ‘masterpieces of European art’ he had seen in Italy in 1924.

Common at the time of the Aztec, the chacmool seems to have originated in the Valley of Mexico with the Toltecs of Tula, although one of its most famous examples is from the Maya city of Chichen Itza in the Yucatan, which at one period became a ‘Tula in the East’ (fig.8). The statue was intimately concerned with sacrifice; the figure half-lying on its back holds a bowl on its stomach, which was to hold the blood of the victim, human or animal. It is not itself a deity, but a warrior, and the examples from Tula and Chichen Itza have carved on the chest the butterfly symbol that indicated the dead hero. The squared headdress and ear-pieces typical of most examples of the chacmool enhance the abrupt twist of the head and its frontal stare at those who would see it from the base of the steps. The whole is more of a mixture of low relief and of carving in the round than one would expect from Moore’s praise of its ‘truth to materials’.

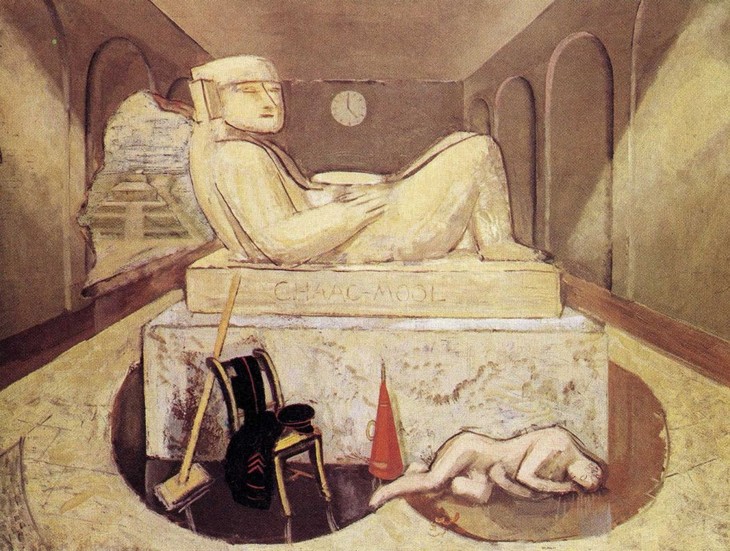

Although Moore wrote predominantly about the formal qualities of the sculpture he admired from other times and other periods – the wonderful phrases ‘form-invention’ and ‘form-knowledge’ recur – he was also curious about the civilisations that made them. No-one whose attention was caught by Aztec art in the 1920s could have been unaware of their fearsome and bloody reputation for human sacrifice. Reaction to this among artists and intellectuals was varied and, taken in conjunction with the challenge to Western aesthetics posed by objects like the chacmools, throws an interesting light on the new ‘friendship between art and anthropology’. Leon Underwood, who gave life-drawing classes at the Brook Green Drawing School attended by Moore in the early 1920s, remained in contact with the young sculptor, publishing prints by him in the journal The Island in 1931. Underwood was passionately interested in and collected primitive art, African and Mexican, and in 1928 went to Mexico. His satirical painting of a chacmool with sacrificial victim reminds us that the subject matter of much Mexican sculpture was not wholly over-ridden by its formal qualities (fig.9). When Moore drafted an essay about Mexican sculpture, probably intended for a student or colleague at some time in the early or mid-1920s, he took a cool view of human sacrifice and very interestingly deflected the practice onto sculpture itself.

The religion of Ancient Mexico from our point was perhaps cruel. Human sacrifice played a large part in their ritual. They had numerous gods and goddesses. When for any reason a new likeness of a god or goddess was wanted, the Mexican sculptors were separated alone away from the rest of the people, given food enough to last them till the work was done, and at the end of the set period they were brought out & the priests chose the one they thought the best and the rest were destroyed.22

Taking on the known fact that sculptors were professionals in the Aztec world, as the early Spanish commentators like Fray Diego Duran and Sahagun had recorded, and unlike what was known of African sculpture, where it was assumed that its makers were anonymous and undifferentiated, Moore identifies with this unusual form of commission, and the idea of destroying the unsuccessful images seems unconsciously to link to the destruction of human life. Moore’s precise source for this story is unclear, but, matter of fact as his telling of it is, his sense of the social and religious urgency, the close ties between ritual, religion, icon and artist is striking.

In 1927, before Moore made contact with them, the surrealists in Paris staged an exhibition combining one of their new artist-recruits and objects from the Americas – Yves Tanguy et Objets d’Amérique – in which works from British Columbia, New Mexico, Mexico, Colombia and Peru were shown, including a version of the great Aztec statue now in the National Anthopological Museum in Mexico City and known as Coatlicue, the name meaning ‘serpent-skirted goddess’, its necklace of hands and hearts symbolising sacrifice (fig.10). In the surrealist exhibition the work was known by one of its several alternative titles, Teoyamici, and to the catalogue of the show the poet Paul Eluard contributed a short essay about human sacrifice in Aztec culture:

So the Aztecs believed that on the eve of the end of the world, pregnant women would be changed into jaguars and would eat men. Locked into reality and tragically persuaded that they could never get out of it, the peopled tombs with images of cruelty and pain, they decorated idols with torn out hearts still beating, blood intoxicated them and on the red river of life, they paid homage to all the pure powers of the soul. Nothing could be done without the outpouring of blood.23

Moore visited Paris at least once a year from 1922 onwards, though there is no evidence he saw this exhibition nor the huge show of Pre-Columbian art the following year at the Musée des arts decoratifs (over twelve hundred objects, of which half were lent by the Trocadéro and the rest from private collections and museums all over the world including Mexico). However, the fact that he bought, in 1928, L’Art précolombien by Adolphe Basler and Ernest Brummer, which was published to coincide with the exhibition in the same year, indicates that he at least knew of it. L’Art précolombien was abundantly illustrated and aimed at ‘scholars, artists, antiquarians and the general public’, giving them the opportunity to ‘make contact with civilisations that only yesterday were still unknown, and whose threshold modern investigations are only beginning to clear.’24 The romance of the lost worlds of American civilisations was a powerful lure and the fact these were ‘high civilisations’ (city-dwelling, literate, etc.) was much commented on by the various audiences in the West. Moore himself noted in the mid-1920s:

At the time of the Spanish Conquest there was in America a people at a high state of civilization and evidences [sic] proving that there had been even higher civilizations there. Historians are still searching for clues which will enable us to read their language – until some such discovery as the Rosetti [sic] stone (which gave us the key to the Egyptian hieroglyphics) our knowledge of them is bound to be very limited, & it will be impossible to date with certainty their architecture & sculpture chronologically with ours.25

Moore may also have known another scholarly publication that appeared at the same time as L’Art précolombien containing an essay by the French dissident surrealist writer Georges Bataille, ‘L’Amérique disparu’ (Extinct America). It was the first salvo of a radical approach to anthropology that disrupted cultural value systems. Here Bataille contrasted the art of the Maya, ‘certainly more human than any other in America’, with that of the Mexicans (Aztecs), who ‘were probably as religious as the Spanish, but who mingled with religion a sentiment of horror, of terror, linked to a kind of black humour even more terrible than horror.’26 Already in his approach could be found the over-turning of conventional values that was to characterise his journal Documents (1929–30). Mayan art was still-born despite the ‘perfection and richness of the work’. The horrific Aztec gods, by contrast, who had an undeniable kinship with the devils and demons of medieval Christianity, were born of a different attitude to the ‘human’, in which the reality of human frailty, its helplessness before the god-phantoms it created to express the terror of the implacable void of heaven, was vividly expressed. The city Mexico-Tenochtitlan was not only a slaughterhouse running with blood but also a remarkably beautiful metropolis, with decorated temples, flowers and canals. This welcoming, even celebration, of the inevitability of death in life had, Bataille inferred, more human reality in it than the elegant realism of the Maya. Although here Bataille did not draw direct connections with modern Europe, shortly afterwards in Documents he was to return many times to the theme, for example, in his entry on ‘Abattoir’ in the magazine’s ‘Critical Dictionary’. Starting from the archaeological point that once temple and slaughterhouse were the same place (the Aztec model perhaps uppermost in his mind), he pointed out that in contemporary European cities slaughterhouses are tucked away in remote corners, as though quarantined, because modern man is unable to face the ugliness of the bloodshed that he nonetheless depends on for his daily meat.27 Bataille’s position may have been extreme in the turning of the anthropological gaze from the distant strangeness of alien societies to those at ‘home’ in Europe, but he certainly contributed to a different reading of the ‘primitive’, in which horror (and humour) had more power and reality than the poetic and imaginative qualities celebrated by surrealist poets like Breton and Benjamin Péret.

Although there is no suggestion of a direct link between Moore and Bataille, there is some common ground, notwithstanding Moore’s more measured and rational means of expression, especially in the drawings of the late 1930s when Moore was forced to contemplate the approach of another war. It is interesting that Moore, unlike Roger Fry, preferred Mexican to Mayan sculpture:

Toltec sculpture is the connecting link between Mayan (which is mostly in relief and highly decorative) & Aztec sculpture. Toltec is rather florid & conventionalised. Aztec sculpture became more & more a style of its own and very distinct from Mayan. It reflects the character of the Aztecs in its rigorous simplicity, power, almost fierceness. I prefer Mexican to Mayan sculpture. Mexican stone sculptures have largeness of scale, and a grim, sublime austerity, a real stoniness. They were true sculptors in sympathy with their material & their sculptures have some of the character of mountains, of boulders, rocks and sea worn pebbles.28

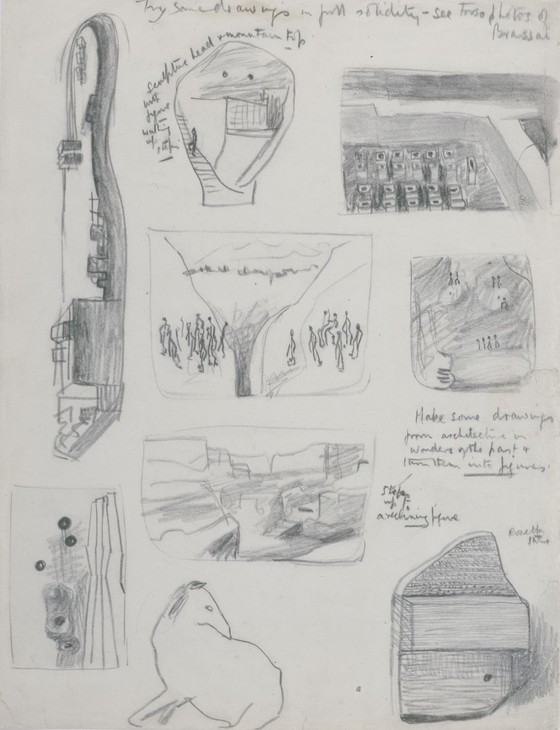

Henry Moore

Ideas for Drawing Subjects 1937

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Menor, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Ideas for Drawing Subjects 1937

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Menor, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

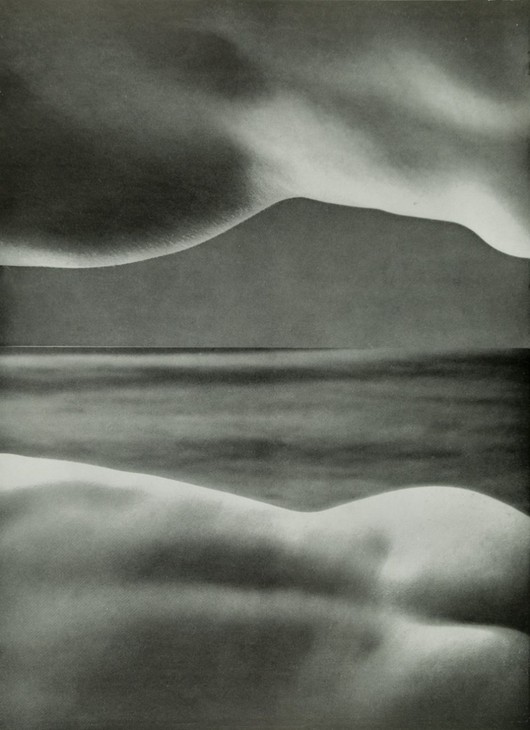

Brassaï

Ciel postiche 1932–4

Published in Minotaure no.6 Winter 1935

Fig.12

Brassaï

Ciel postiche 1932–4

Published in Minotaure no.6 Winter 1935

Although he expresses his preference in modernist terms, emphasising their truth to materials (in this case stone), a drawing bears witness to his consciousness of Mexican sculpture’s link to human sacrifice. This is on a sketchbook page from 1937, crowded with small drawings with clear connections to surrealism.29 The potential of the drawn image to follow the imagination into realms difficult for sculpture to follow takes several fascinating directions, and shows Moore experimenting with double images (fig.11). One of these also has a bearing on the chacmool/reclining figure conjunction. A note at the top reads: ‘Try some drawings in full solidity – see torso photos of Brassaï.’ The Brassaï Moore probably has in mind is Ciel postiche, which was reproduced in Minotaure in 1935 (fig.12). It makes a fascinating comparison with Moore’s desire to combine figure and landscape. Brassaï juxtaposed front and back views of a nude torso photographed against indeterminate backgrounds, thereby turning them into landscape – mountain and sea. This brilliant visual play clearly fascinated Moore, and two of the sketches on this page pursue the idea of the double image, which derived from the painter Salvador Dalí. At top left an elongated landscape with building is turned ninety degrees, with the potential to become a vertical abstract figure like those Moore endlessly sketched. At the centre top is a small, contained sketch that doubles as head and architecture: ‘sculpture head and mountain top with figure walking up steps’. The head, with two dot-eyes and a grill-form (Parthenon, prison, teeth) could be seen as an ancestor of his later metal sculpture heads, and his ‘forms within forms’. But it is a small drawing towards the bottom of the sheet in the centre that brings quietly to the surface an underlying resonance of the chacmool/reclining figure theme. A quite crowded architectural scene is annotated ‘steps up to a reclining figure’. The structure with the steps to the right of the sketch is unmistakably that of a Mexican temple platform, from what were known in Moore’s time as ceremonial centres – Teotihuacan, Tula or one of the Aztec sites. The chacmool/reclining figure – a tiny dark note on the page – is half enclosed by walls, and there is a rough indication beyond it of a rising temple. This evocation of a Mexican ritual building with all its implications of sacrifice and bloodshed is a rare, perhaps unique instance of the reclining figure shown in its original context. Moore had not forgotten this, even if the reclining figure has already by repetition become accepted in more humanist, and predominantly female, terms. It brings us back to the original chacmool and its fascination for Moore – ‘about as good a piece of sculpture as I know’.30 Did Moore have a sense of the uncanny in this sculpture, in which symbol, gesture and posture build up to the death in life, or life in death ambiguity? The shock of the abruptly turned head, above a neck that is clearly severed; the hard rectangular ear pieces, the combination of incision, low relief and carving in the round, the whole figure of a piece with its pedestal out of which it rises, these formal qualities marry perfectly with its terrible alertness.

Moore and painter Rufino Tamayo visting the carved stone ruins at Xochicalco, Mexico in 1953

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.13

Moore and painter Rufino Tamayo visting the carved stone ruins at Xochicalco, Mexico in 1953

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Photograph by Henry Moore of a sixteenth-century stone cross, Mexico in c.1953

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.14

Photograph by Henry Moore of a sixteenth-century stone cross, Mexico in c.1953

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Henry Moore Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6

Tate T02274

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.15

Henry Moore

Henry Moore Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6

Tate T02274

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In a notebook of 1926 Moore admonished himself to, ‘Keep ever prominent the world tradition | the big view of sculpture’.32 He knew there was no single such tradition but an inexhaustible resource of art and of sculptural ideas in many cultural contexts. In keeping this in mind, and mining it in his practice, Moore helped to widen the possibilities of cultural exchange and broaden the very notion of what sculpture is.

Notes

See Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, especially ‘World Cultures’ section, pp.95–125.

John and Vera Russell, ‘Conversations with Henry Moore’, Sunday Times, 17 and 24 December 1961, reprinted in Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, p.201.

Carl Einstein, Negerplastik (1915), quoted in Colin Rowe, Primitivism and Modern Art, London 1994, p.117.

Henry Moore, ‘Negro Sculpture’, in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002 p.98.

Guillaume Apollinaire ‘A propos l’art des noirs’, in Paul Guillaume, Sculptures nègres, Paris 1917, n.p.

Much of Lévi-Strauss’s fieldwork took place in the Americas, where he avoided Mexico and the central American civilisations because they had a literary tradition going back to Pre-Columbian times, which he regarded as incompatible with the ‘savage mind’.

Henry Moore, ‘Primitive Art’, Listener, vol.25, no.641, 24 August 1941, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.102.

Rhodes 1994, p.17. The first study of primitivism in modern art was Robert Goldwater, Primitivism in Modern Painting, New York 1938. In 1984 an ambitious and highly controversial exhibition took place at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, called ‘Primitivism’ in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and Modern. Juxtaposing ‘tribal’ art and work by modern and contemporary artists, it was accused not only of a patronising attitude but also of failing to respect the contexts in which much of the former was made. See James Clifford, The Predicament of Culture, Harvard 1988. Similar debates were sparked by the exhibition in Paris in 1989, Magiciens de la terre, which brought together work by contemporary artists and ‘indigenous practitioners’. See Jean Fisher ‘Other Cartographies’, Third Text, vol.3, no.6, 1989.

Susan Hiller, ‘“Truth” and “Truth to Material”: Reflecting on the Sculptural Legacy of Henry Moore’, in Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell (eds.), Henry Moore: Critical Essays, Aldershot 2003.

For a fuller survey of Moore’s borrowing from Mexican art see Barbara Braun, ‘Henry Moore and Pre-Columbian Art’, Res, nos.17/18, 1989,.

Paul Eluard, ‘D’un véritable continent’, in Yves Tanguy et Objets d’Amérique, exhibition catalogue, Galerie surréaliste, Paris 1927.

Moore, ‘Mexican Sculpture’. Since Moore wrote these unpublished notes in the mid-1920s, the state of knowledge of the Aztec and Toltec, but most particularly of the Maya and Olmec, has changed dramatically. Over the last three decades or so Maya hieroglyphic writing has been largely deciphered, thanks to the Russian epigrapher Yuri V. Knorosov and others, allowing us to date cities, battles, kings, queens, monuments and art. The great antiquity of the Olmec, who had writing and a complex calendar, at the beginning of the first millennium BC, was finally agreed in 1942 and the latest research was published in the early 1940s in DYN (nos.4–5 and 6).

Jean Babelon, Georges Bataille and Alfred Métraux, ‘L’Amérique disparu’, in L’Art pré-colombien, Cahiers de la République des lettres, des sciences et des arts, vol.11, Paris 1928, p.10.

Dawn Ades is Professor Emeritus at the University of Essex.

How to cite

Dawn Ades, ‘Henry Moore and World Sculpture’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www