Muscular Modernism

Why did Gaudier-Brzeska focus so incessantly on the subject of wrestlers and wrestling in the period before the First World War? He was clearly fascinated by the artistic possibilities offered by the depiction of the wrestling match: numerous sketches, drawings, two sculptures and one linocut were made between 1912 and 1914. He was, however, not the only modern artist at the beginning of the twentieth century interested in wrestling, boxing and the pugilistic arts. As the literary historian Kasia Boddy has argued in her work on the cultural history of boxing, pugilism has offered writers and artists not only a subject for art but ‘the basis for a method’.1 The art of the early twentieth century, or particular strands of it at least, not only became more violent or combative in terms of subject matter, but also in rhetoric and description. According to its protagonists, modern art (and modern sculpture in particular) was hard, tough, muscular, masculine and ‘primitive’. Gaudier-Brzeska’s wrestlers, in their many variations, undoubtedly connected the new (if somewhat anxious) enthusiasm for modern muscle and the aesthetic, material and ideological potential of the fight.

Frederic, Lord Leighton

An Athlete Wrestling with a Python 1877

Bronze

1746 x 984 x 1099 mm, 290 kg

Tate N01754

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1877

Tate

Fig.1

Frederic, Lord Leighton

An Athlete Wrestling with a Python 1877

Tate N01754

Tate

If physicality had been central to the concerns of late Victorian sculptors, it remained crucial, as the art historian David Getsy has highlighted, ‘to the definition of sculptural modernism’.5 Yet modern artists at the beginning of the twentieth century were at pains to signal difference from this nineteenth-century celebration of muscle and what they saw as an academic and classical conception of the male nude. Indeed, the classical wholeness sought by Victorian sculptors was ridiculed with bombastic and frequently homophobic rhetoric by early twentieth-century modernists. Although he had once drawn and sculpted a copy of the Farnese Hercules, Gaudier-Brzeska soon distanced himself from the classically inspired body of the athlete. The modern sculptor, according to Gaudier-Brzeska, was no longer inspired by ‘the pretty works of the great Hellenes’, but ‘to the tradition of the barbaric peoples of the earth’.6 As the art historian Lisa Tickner has noted, ‘Greek sculpture evokes “Greek love”’.7 Here Gaudier-Brzeska is quite clearly associating the ‘pretty works’ of classical sculpture – and by association, the neo-classical sculpted bodies of male athletes and muscle men created by his nineteenth-century predecessors – with homosexuality.

Rather than faithfully depicting individual sinews, veins and muscular bulges like the late Victorian New Sculptors, early twentieth-century modernist artists became increasingly interested in the rhetoric of muscle and violence embodied by athletes, wrestlers and fighters.8 Gaudier-Brzeska’s wrestlers are an interesting case in point. While he began by making fairly naturalistic drawings of bodybuilders and muscular athletes observed in the wrestling gym and the life class, Gaudier-Brzeska moved away from the study of anatomy and musculature towards depicting the scene and aesthetics of combat itself. His fighters in the sculpted relief and the associated drawings are no less large but are certainly less anatomically detailed. They become increasingly abstract and Gaudier-Brzeska’s interest in ‘primitive’ sculpture and carving becomes more apparent in the period that he was focusing on wrestling. Gaudier-Brzeska moved his nude male wrestlers away from a Greco-Roman heritage (with which, following the revival of the Olympics in 1896, wrestling had long been associated) towards a more ‘barbaric’ and ‘primitive’ conception of the sculpted, wrestling body. Fighting was regularly celebrated by modernist artists and writers as something that was ‘primitive’, instinctual, and elemental. This was an idea that Gaudier-Brzeska’s contemporary, Wyndham Lewis, expressed in his ink and pastel drawing, Combat No.2 1914 (Victoria and Albert Museum, London), in which three pairs of figures engage in furious, energetic and violent scuffles.9

It is useful here to think again about Kasia Boddy’s description of pugilism not only as a ‘subject’ but as a ‘method’ for artists and writers. At the same time that Gaudier-Brzeska was depicting wrestling and violence, he was also writing about modern sculpture using a language of force, strength and power. The ‘modern sculptor’, he wrote in the avant-garde journal, the Egoist, is a man who works with instinct as his inspiring force ... The shape of a leg, or the curve of an eyebrow, etc. Etc., have to him no significance whatsoever; light voluptuous modelling is to him insipid – what he feels he does so intensely’.10 Those who watched Gaudier-Brzeska sculpt were often alarmed by the violence and force of his technique as he pummelled his materials into submission. According to the artist’s sometime sitter Enid Bagnold, his manner could be just as gruff: ‘Gaudier-Brzeska was like a dagger in the midst of us ... He talked like a chisel and argued like a hammer.’11 Although not a trained wrestler or boxer, the artist frequently honed his strength and stamina out of the studio by getting himself tangled up in street brawls and fights. He made a knuckleduster cut from brass for the philosopher T.E. Hulme, who was not adverse to a punch-up himself;12 and there is even an account of Gaudier-Brzeska knocking the driver of a horse and carriage unconscious in Soho.13

William Roberts

Sparring Partners c.1919

Watercolour and graphite on paper

355 x 255 mm

Tate T11792

Bequeathed by Pauline Vogelpoel, Director of the Contemporary Art Society, 2002, accessioned 2004

© The estate of William Roberts

Fig.2

William Roberts

Sparring Partners c.1919

Tate T11792

© The estate of William Roberts

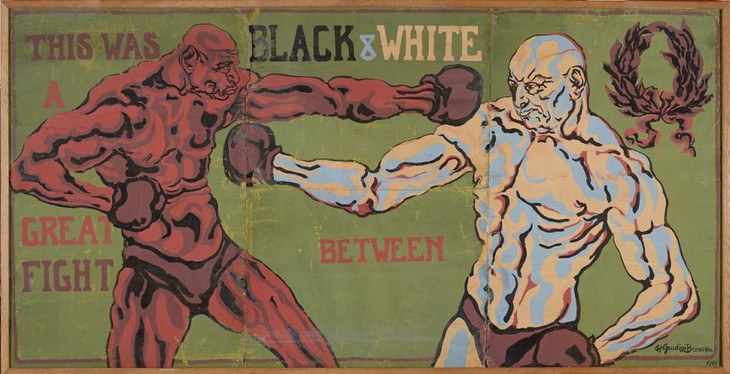

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

1911 'Black & White' poster (also known as Boxers)

Gouache on paper

1020 x 2020 mm

Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge

Fig.3

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

1911 'Black & White' poster (also known as Boxers)

Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge

Gaudier-Brzeska was certainly not alone in using a visual and textual language of force and fight in the construction of his artistic persona. Boddy observes that the ‘language of boxing provided experimental artists [in the early twentieth century] with metaphors for talking about a range of issues from forceful assertion to forceful control, from the status of individual character to the stance of an audience or reader’.14 Gaudier-Brzeska’s studies of wrestlers, bodybuilders and fighters should be viewed within this early twentieth-century context of aesthetic violence and combat, one that captivated fellow artists Wyndham Lewis and William Roberts (fig.2).15 Gaudier-Brzeska had already turned to the image of the boxing match in 1911 when he produced a poster design for Black & White Scotch whisky (fig.3). Accompanied by the slogan, ‘THIS WAS A GREAT FIGHT BETWEEN BLACK & WHITE’, Gaudier-Brzeska depicts a black and a white fighter throwing brutal punches at each other. Their heavily muscled torsos are matched by expressions of extreme exertion. Just a year before, the fight between ‘Jack’ Johnson and Jackson Jeffries had caused a media storm centred on the racial politics of a fight between a black and a white boxer (it was widely billed as the ‘fight of the century’, despite taking place only ten years into that century).

‘Modernism truly became the great age of sport’, notes the cultural historian Harold B. Segel:

Public interest and enthusiasm in it had never been as high, nor was it gender limited. As might be expected, popular culture embraced the world of sport and the athlete with astonishing exuberance. But high culture was not to be found wanting. Artists delighted in the new subject matter and responded appropriately. Boxing, wrestling, soccer, cycling, and field and track became as familiar on canvas and in print as on billboards.16

Despite this, there has been very little work carried out on the relationship between the revival of sports such as wrestling and modern art in early twentieth-century Britain. Scholarship has instead focused on nineteenth-century physical culture, or the connections between artists and the concept of the body under fascist regimes in the twentieth century. There is still much work to be done on the interrelationships between sport and modernism in the period in which Gaudier-Brzeska made his Wrestlers relief.17 As cultural historian Steven Connor has puzzled: ‘It seems odd that, when so many other features of modern leisure and entertainment – gramophones, radio, cinema, shopping, tourism – should have aroused the curiosity of cultural historians interested in the sometimes tense relations between artistic modernism and sociopolitical modernity, there should seem so little to say about sport.’18 Perhaps this is because sport was ‘blasted’ in the first issue of the journal Blast, the published organ of the pre-First World War avant-garde vorticist movement in Britain, which was edited and largely written by Wyndham Lewis, and in which the work of Gaudier-Brzeska was also featured. If sport was ‘blasted’, it was probably the sport of public schools, elite universities (the ‘Varsity’ matches), imperial leagues and cricket pitches that Lewis and friends had in mind. Instead, it was professional fighters and music hall stars that were ‘blessed’ in Blast (eleven fighters and performers in total). As art historian Richard Cork has written, ‘the manifestoes of Blast No.1 combine the aggression of the boxing-ring with the raucous aplomb of a music hall song’.19

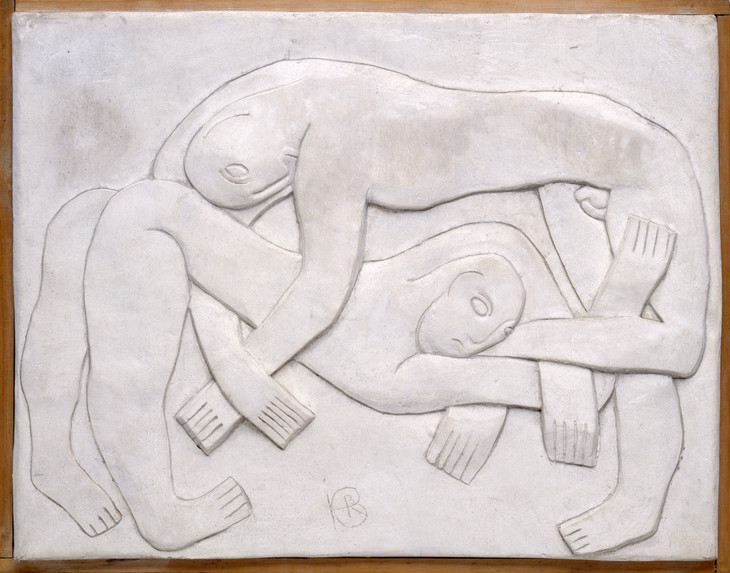

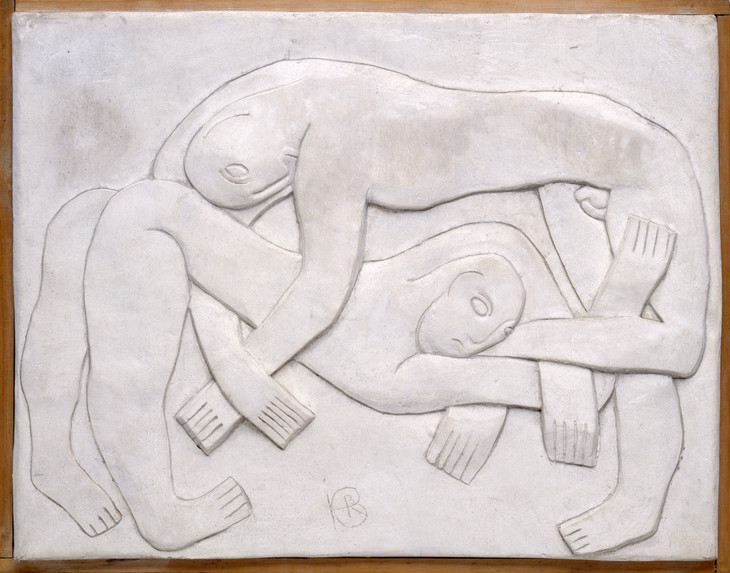

Looking at Gaudier-Brzeska’s Wrestlers relief again (fig.4), perhaps there is a touch of the ‘raucous aplomb’ and slap-and-tickle humour of the Edwardian music hall, especially in the expressions on the wrestlers faces. ‘Knockabout’ acts were popular on the stages of London and wrestling often featured at carnivals and country fairs. The Griffiths Brothers were one well-known music hall duo whose sketch, ‘The Motor Car and the Duel’, ended in a wrestling bout between a Frenchman and an Englishman.20

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Wrestlers 1914, cast 1965

Plaster

711 x 927 x 76 mm

Tate T00837

Presented by Kettle's Yard Collection Cambridge 1966

Tate

Fig.4

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Wrestlers 1914, cast 1965

Tate T00837

Tate

Looking at Gaudier-Brzeska’s Wrestlers relief again (fig.4), perhaps there is a touch of the ‘raucous aplomb’ and slap-and-tickle humour of the Edwardian music hall, especially in the expressions on the wrestlers faces. ‘Knockabout’ acts were popular on the stages of London and wrestling often featured at carnivals and country fairs. The Griffiths Brothers were one well-known music hall duo whose sketch, ‘The Motor Car and the Duel’, ended in a wrestling bout between a Frenchman and an Englishman.20

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

The Wrestlers 1913

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig.5

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

The Wrestlers 1913

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Wrestling revival

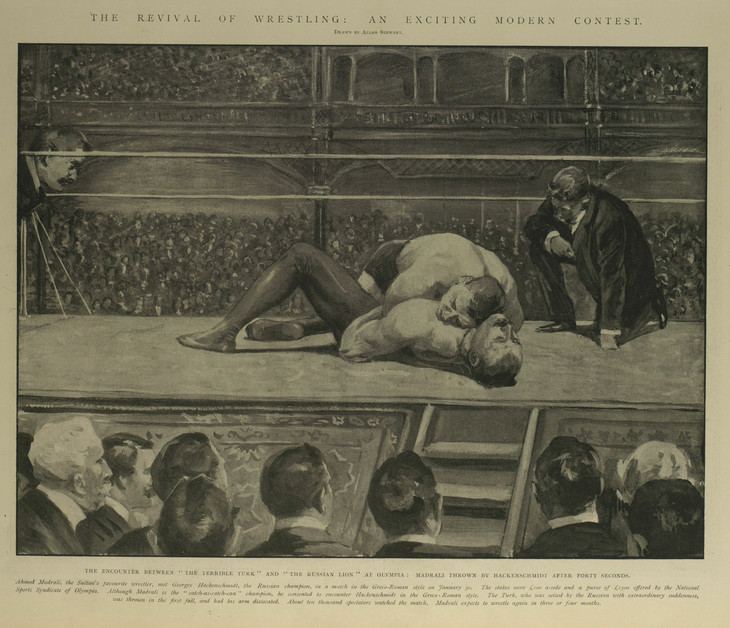

Allan Stewart, The Revival of Wrestling: An Exciting Modern Contest, published in the London Illustrated News, 6 February 1904

Fig.6

Allan Stewart, The Revival of Wrestling: An Exciting Modern Contest, published in the London Illustrated News, 6 February 1904

Gaudier-Brzeska created his sculptures and drawings of wrestling at a moment when the sport was undergoing a revival, not only in Britain but around the globe, in the decade or so before the First World War. Aficionados of the sport frequently see this as the golden era of the sport, uncorrupted by the ‘fraudulent play-acting that passes for wrestling’ in the present – a reference to the televised spectacles of American World Wrestling Entertainment.25

As has already been suggested, the Wrestlers relief is not a straightforward depiction of a wrestling match or of wrestlers. Nevertheless, this sculptural relief does connect very specifically to the moment of its making and the social and sporting spaces to which it refers. As a work of art, it prompts consideration of the connections between avant-garde art, popular culture and sport before the First World War. At the beginning of the twentieth century, wrestling was a highly visible sport. It was extremely popular in London and around the country where regional variations were (and still are) practised and protected with vigour. From the Kinetoscope parlour on Oxford Street where, for a small fee, one could watch moving images of wresters, to Eadweard Muybridge’s photographs of wrestlers in his book The Human Figure in Motion (1901), to the numerous photographs and representations of wrestling in sporting journals and daily newspapers (fig.6), wrestling was an omnipresent part of Edwardian visual culture. Writing in the Times in January 1911, one journalist noted, ‘Of later years there has been a remarkable revival of interest in boxing and wrestling; and the contests between professional experts are watched by large gatherings of spectators who are willing to pay as much as a guinea, or even more, for a seat at the ring side’.26 Indeed, the writer claimed that every class of British society, women included, was to be found in the audiences of wrestling matches.

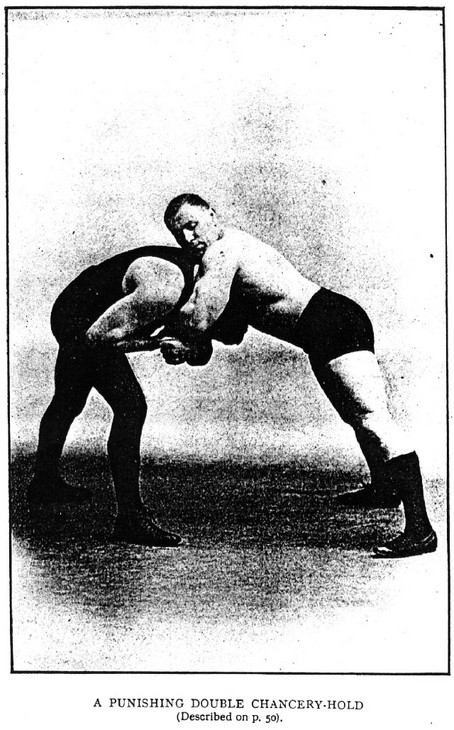

There were several highly publicised matches in this period that made fighters worldwide celebrities. A bout in Chicago on 4 September 1911 between the American wrestler Frank Gotch and the Estonian-born but London-based George Hackenschmidt (who upon winning was recognised as the first World Heavyweight Champion) drew a crowd of over 30,000 spectators and was featured in newspapers and magazines all over the world. As well as photographs of such matches, wrestling manuals also featured images of different holds. Hackenschmidt’s Complete Science of Wresting (published by Health & Strength in 1909) contained seventy images of standing holds, ground wrestling and throws (fig.7). The paused embrace of Gaudier-Brzeska’s Wrestlers relief suggests an awareness of these mass produced images of suspended action or movement.

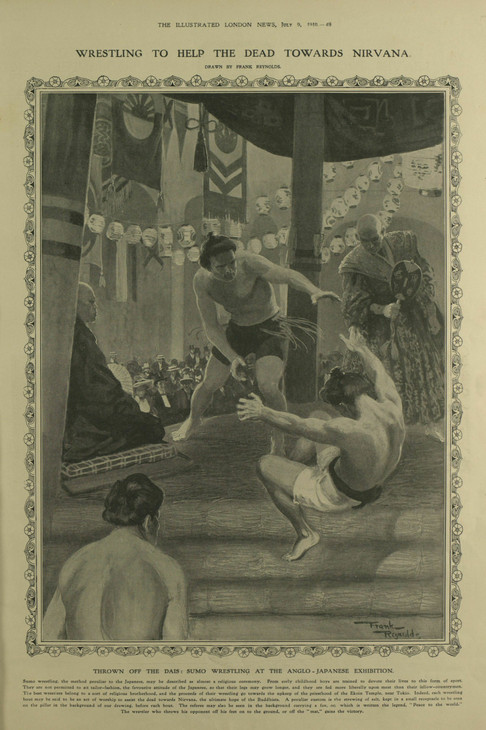

Wrestling and the figure of the wrestler were explicitly connected to national and imperial politics. While wrestling and boxing were frequently celebrated as ‘national’ sports in Britain, the early twentieth-century press brimmed with anxious articles about the physical prowess of foreign fighters. Indian wrestlers were particularly revered. Ahmud Bux was one Indian wrestler who awed the British crowd. A report on his match with the Swiss fighter, de Riaz, noted that:

Evidently it will be difficult to find heavyweights good enough to beat these Indians, who have the look of all round athletes, possessing long elastic muscles, great pace, and quickness of vision – qualities generally absent in the continental wrestler who is the product of the gymnasium.27

Frank Reynolds, Wrestling to Help the Dead Towards Nirvana, published in Illustrated London News, 9 July 1910

Fig.8

Frank Reynolds, Wrestling to Help the Dead Towards Nirvana, published in Illustrated London News, 9 July 1910

Wooden human figure, from Hawaii, Polynesia, possibly 18th century AD

670 mm (length)

AOA 1657

Henry Christy Collection. Probably formerly owned by the United Service Museum

Photo © Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.9

Wooden human figure, from Hawaii, Polynesia, possibly 18th century AD

AOA 1657

Henry Christy Collection. Probably formerly owned by the United Service Museum

Photo © Trustees of the British Museum

Gaudier-Brzeska’s sculpted relief of two naked fighters alludes to the wrestlers he drew in the gym at the headquarters of the London Amateur Wrestling Association – the ‘two athletic types, large shoulders, taut, big necks like bulls’,31 as he described them – but there are other bodies that are suggested too: sculpted bodies ancient and modern, the bodies of fighters photographed in the newspapers, the body of the naked male model in the life class, the body of the sculptor. Gaudier-Brzeska described the wrestlers he saw as having reached a ‘state of perfection’.32 In the relief he tried to recreate that state through a controlled balance of bodies, shapes and forms and it was in the permanent materials of sculpture that, for him, this state could be achieved and preserved.

Notes

Michael Hatt, ‘Physical Culture: The Male Nude and Sculpture in Late Victorian Britain’, in Elizabeth Prettejohn (ed.), After the Pre-Raphaelites: Art and Aestheticism in Victorian Britain, Manchester 1999, p.244.

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, draft letter to the Egoist, 1914, Tate Archive TGA 91133. Lisa Tickner was the first art historian to discuss the draft and the letter that was subsequently published in the Egoist, 16 March 1914, pp.117–8. See Lisa Tickner, ‘Now and Then: The Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound’, Oxford Art Journal, vol.16, no.2, 1993, p.57.

The term ‘New Sculpture’ was coined by critic Edmund Gosse in 1894 to describe a greater degree of naturalism in late Victorian sculpture, inspired in part by the much admired example of Leighton’s Athlete Wrestling with a Python 1877.

Wyndham Lewis, Combat No.2 1914, http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O138698/combat-no-2-drawing-lewis-wyndham/ , accessed 3 May 2012.

See Jon Wood, ‘Ornaments, Talismans and Toys: The Hand-Held Sculptures of Henri Gaudier-Brzeska’, in Blasting the Future: Vorticism in Britain 1910–1920, exhibition catalogue, Estorick Collection, London 2004, pp.41–8.

See also Jonathan Black, ‘“THE MOVING AGENT”: Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Primitivism, Technology and Violence’, in ‘WE the Moderns’, Gaudier-Brzeska and the Birth of Modern Sculpture, exhibition catalogue, Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge 2007, pp.89–97.

Harold B. Segel, Body Ascendant: Modernism and the Physical Imperative, Baltimore and London 1998, p.5.

Mike O’Mahony’s work is a particular exception and has led the way in exploring these relationships. See Sport in the USSR: Physical Culture – Visual Culture, London 2006, and Olympic Visions: Images of the Games through History, London 2012. Lynda Nead's work is also important for discussions of aesthetics and violence. See ‘Stilling the Punch: Violence and the Photographic Image’, Journal of Visual Culture, vol.10, no.3, 2011, pp.305–23.

Steven Connor, ‘Sporting Modernism’, an expanded version of a talk presented at the Centre for Modernist Studies, University of Sussex, 14 January 2009, http://www.stevenconnor.com/sportingmodernism/sportingmodernism.pdf , p.2, accessed 3 May 2012.

See George Cooke’s 1907 caricature of the Griffiths Brothers (Victoria and Albert Museum, London), http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O86134/caricature-cooke-george , accessed 3 May 2012.

Jon Wood, ‘Heads and Tales: Gaudier-Brzeska’s Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound and the Making of an Avant-Garde Homage’, in David Getsy (ed.), Sculpture and the Pursuit of a Modern Ideal in Britain, c.1880–1939, Aldershot 2004, p.199.

Gilbey 1986, p.83. It was American ‘all-in wrestling’ that inspired the French philosopher Roland Barthes to write that ‘Wrestling is not a sport, it is a spectacle’. Roland Barthes, ‘The World of Wrestling’, Mythologies, trans. by Annette Lavers, New York 1984, pp.15–25.

How to cite

Sarah Victoria Turner, ‘Muscular Modernism’, July 2013, in Sarah Turner (ed.), In Focus: 'Wrestlers' 1914, cast 1965, by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Tate Research Publication, July 2013, https://www