Walter Richard Sickert The Tottenham Distillery c.1924

Walter Richard Sickert,

The Tottenham Distillery

c.1924

This painting shows the interior of a canteen or public eating house, rendered in loosely handled paint, allowing the white ground of the primed canvas to show through at the edges of colours. The man in white chef’s uniform prepares food, perhaps for a waiting customer indicated by the table in the right foreground. Sickert painted this everyday London scene after his return from Dieppe following the death of his second wife.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Tottenham Distillery

c.1924

Oil paint on canvas

508 x 610 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Sickert’ in black paint bottom left

Bequeathed by Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck 1940

N05086

c.1924

Oil paint on canvas

508 x 610 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Sickert’ in black paint bottom left

Bequeathed by Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck 1940

N05086

Ownership history

Purchased by Lord Henry Cavendish-Bentinck, London, from the Savile Gallery, London, 1926 (28); by descent to his wife, Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck, on his death 6 October 1931, by whom bequeathed to Tate Gallery 1940.

Exhibition history

1926

Exhibition of Paintings by Walter R. Sickert, Savile Gallery, London, May–June 1926 (28).

1942

The Tate Gallery’s Wartime Acquisitions, National Gallery, London, April–May 1942 (117).

1942–3

A Selection from the Tate Gallery’s Wartime Acquisitions, (Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts tour), Royal Exchange, London, July–August 1942, Cheltenham Art Gallery, September 1942, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, October 1942, Galleries of Birmingham Society of Arts, November–December 1942, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, January–February 1943, Victoria Art Gallery, Bath, February–March 1943, National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, March–April 1943, Manchester City Art Gallery, April–May 1943, Philharmonic Hall, Liverpool, May–June 1943, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh, June 1943, Glasgow Museum and Art Gallery, Kelvingrove, July 1943, Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne, August 1943 (79).

1960

11th Hintlesham Summer Festival, Hintlesham Hall, Ipswich, July–August 1960 (no catalogue found).

1971–89

Paisley Museum and Art Gallery, Renfrewshire, February 1971–January 1989 (long loan).

1989–90

W.R. Sickert: Drawings and Paintings 1890–1942, Tate Gallery, Liverpool, March 1989–February 1990, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1990 (15, reproduced).

1998

Two British Impressionists: Walter Sickert and Philip Wilson Steer, Norwich Castle Museum, January–April 1998 (32, reproduced).

2004

Walter Richard Sickert: The Human Canvas, Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, July–October 2004 (36, reproduced).

2010

The Art of Walter Sickert, The Lightbox, Woking, May–July 2010 (no catalogue).

References

1960

Lillian Browse, Sickert, London 1960, p.102.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, p.628.

2006

Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, p.489, no.572, reproduced.

Technique and condition

Walter Sickert chose a coarse, fairly open-weave canvas for this painting. The cloth is probably linen that has been stretched unevenly. The white primer has air bubbles throughout, suggesting that it had been mixed vigorously before application in what appears to be a tempera or oil emulsion medium, commonly found on Sickert’s works from around 1914 (see also Tate N05092). It is likely that the stretcher frame was purchased separately and the canvas stretched and prepared by the artist, although he had purchased commercially prepared canvases with ‘absorbent grounds’ previously.

Sickert squared up the canvas for painting. He then started by drawing with paint and blocking in the principal tones in pinks and pale greens applied leanly by brush, although this in part comes from the absorbent ground. After leaving the work to dry, he further reinforced his squaring-up lines over the first painting, perhaps using a ‘grille’ (see also Tate T03360). He then worked over the composition at least once but probably more adjusting the details within the overall drawing. His later paint is more thickly applied with brushed impasto from a well-loaded brush and it shows local wet-in-wet mixing from the same campaign. Much white ground remains visible where Sickert has not painted up to the boundary between colours, as he described in a letter to his friend Ethel Sands:

One or the other thing is apt to happen. Either the brush stops short of or exactly at the boundary of a form, or ... the paint leaves a too exuberant ridge of wet paint (as Whistler did in the Japanese period) which is ‘beastly’ ... Now why when we are working from nature is it difficult to avoid either starving or slopping? Because we are afraid of losing the form expressed by the boundaries so difficult to find & so easy to lose.1

In places the paint is washed quite thinly and in other parts scrubbed thickly and hard across the surface, often bouncing across the earlier dried surface in clear brushstrokes. The image appears unresolved in places and remains unvarnished. However, it does not appear to be an unfinished work (see Tate N05087), and features such as the squaring-up seem to be left deliberately visible as evidence of the painting process.

Stephen Hackney

November 2004

Notes

How to cite

Stephen Hackney, 'Technique and Condition', November 2004, in Nicola Moorby, ‘The Tottenham Distillery c.1924 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, September 2005, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Walter Sickert used places in a similar way to people, drawing inspiration from favoured subjects until he exhausted their artistic possibilities and then abandoning them in search of new motifs. In 1922, after his wife Christine’s death, he returned to England from Dieppe and sought the comfortable familiarity of his favourite London haunts. He took a bedsit at 15 Fitzroy Street and resumed work in his studio behind the building, the ‘Frith’.1 Although initially reclusive, Sickert gradually resumed connections and habits from his old life, dining out with friends, visiting local establishments and rediscovering his love of the city. He no doubt drew personal strength and comfort from his old stamping ground, but professionally he seems to have reached an artistic impasse. The Tottenham Distillery is one of a small number of London scenes that Sickert painted during this period. He quickly tired of the area around Fitzroy Street and Camden Town that was already so well known to him. In the spring of 1924, in search of a new source of inspiration, he moved to rooms at Noel Street in Islington, and this part of London henceforth became the subject of a number of landscapes. It seems likely that The Tottenham Distillery belongs to the period prior to this move and therefore dates from around 1922–4. Another interior from this time is The Bar Parlour 1922 (private collection),2 which probably depicts the bar of the Bachelor’s Hotel, Covent Garden, where Sickert stayed for a time in 1922.3

The Tottenham Distillery is a portrayal of a scene of everyday life characteristic of Sickert’s detached, objective stance. With its half-seen forms and ambiguous title, it is simultaneously acutely observed and misleadingly confusing. The painting appears to show the corner of a canteen or public eating house. In the centre of the room is a blackboard covered in white chalk writing, presumably the menu or daily specials although the script is indecipherable. There are two men occupying the room who stand absorbed in tasks with only a profile view visible to the viewer. The man on the left dressed in a white chef’s tunic and hat appears to be preparing food on a stove or open grill against the wall. He is perhaps in the process of frying since a small curl of smoke rises up from the counter. The other man, standing apart and to the right, is dressed in dark brown-green and may also be preparing or helping himself to food. He seems to have a cloth thrown over his left shoulder and is standing underneath an overhanging metal canopy. A chair and table occupy the right-hand corner of the painting suggesting the presence of a customer waiting for food.

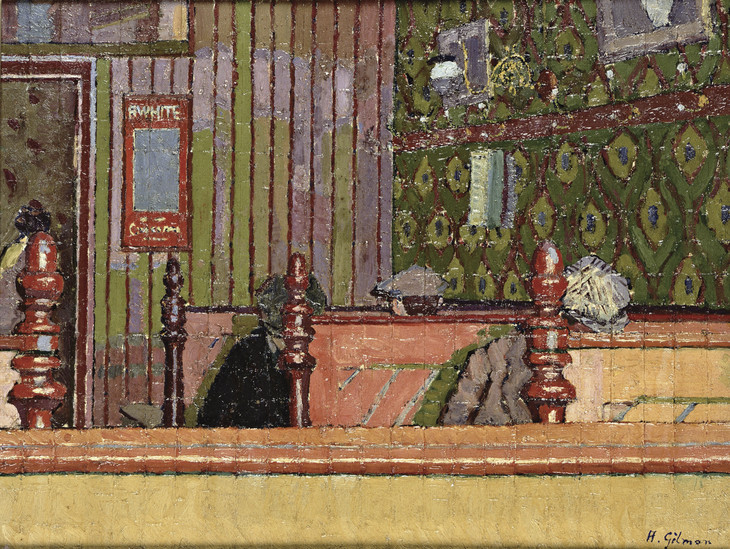

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

An Eating House c.1913–14

Oil paint on canvas

572 x 749 mm

Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust

Photo © Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.1

Harold Gilman

An Eating House c.1913–14

Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust

Photo © Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

The identity of the ‘Tottenham Distillery’ remains something of a mystery. The location of the interior in Sickert’s painting has never been confirmed and no record of a pub of that name has been discovered, although Sickert’s friend Sylvia Gosse believed that there was a pub called the Tottenham Distillery in, or around, the Tottenham Court Road area which Sickert regularly visited for lunch.5 Similarly, in an article on the Slade School of Fine Art in the Burlington Magazine of June 1943, the artist Randolph Schwabe recalled that the Head of the School, Frederick Brown, was often seen with members of his staff at a nearby ‘old fashioned tavern called “The Tottenham Distillery” where the food was ... good’.6 Sickert taught briefly at the Slade and was friendly with a number of teachers and ex-pupils. It is possible that Gosse and Schwabe were referring to The Tottenham, a Victorian pub that still stands at 6 Oxford Street, very close to the junction with Tottenham Court Road. According to the Tate Gallery’s former Assistant Keeper, Dennis Farr, the proprietor of The Tottenham had known the area well for some forty years and had no recollection of another establishment with a similar name.7 Against this theory is the appearance of the interior in Sickert’s painting. The Tottenham pub has survived virtually unchanged from the nineteenth century and has retained its original Victorian fittings. Its elaborate decorative scheme of ceramic tiles, painted murals, carved wooden panels and a glass-domed ceiling bears no resemblance to the plain green walls in the painting. The less ornate downstairs bar does have dark wood panelling halfway up the walls that might correspond with the details in Sickert’s painting, but this theory is discouraged by the low ceiling and small size of this room.

The Tottenham Distillery demonstrates Sickert’s interest in creating successful compositional and painterly effects using a subject derived from everyday life. The loosely handled and textural qualities of the paint reduce the visible detail of the interior and figures and render the narrative content of the scene almost obsolete. In an article on the Cavendish-Bentinck collection from 1928, a critic in the Times cites the painting as an example of the artist’s ability to find subjects worthy of art among the mundane and everyday: ‘with its apparently casual and yet so happy arrangement and complete realization by loosely related tones [the painting] shows his extraordinary capacity for finding pictorial subjects in unexpected places – by selection of essentials, one would say, rather than by adopting a particular point of view.’8

There are no known related preparatory studies for The Tottenham Distillery. A watercolour drawing of the same title, however, depicts a seated man lounging in a chair dressed in a tall chef’s hat and a long white apron and sporting a carefully styled moustache and pointed beard. The sitter fills the picture plane with authority and presence, unlike the detached anonymous figures in Tate’s painting. Also known as Monsieur Pomposo, the drawing was reproduced in Drawing and Design in 1927, and, like Tate’s painting, was first sold and exhibited at the Savile Gallery.9 Another drawing called Sauceialiste also shows the same figure. The art historian Wendy Baron has suggested that these two studies may relate to a painting exhibited at the Goupil Gallery in 1922 called Le Repos du Chef.10

The painting was bequeathed to the Tate Gallery by Lady Cavendish-Bentinck whose husband, Lord Henry Cavendish-Bentinck, was a significant collector of modern art (see Tate N05088).

Nicola Moorby

September 2005

Notes

Reproduced in Harold Gilman and William Ratcliffe, exhibition catalogue, Southampton City Art Gallery 2002, p.27.

Randolph Schwabe, ‘Three Teachers: Brown, Tonks and Steer’, Burlington Magazine, vol.82, June 1943, p.145.

Related biographies

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘The Tottenham Distillery c.1924 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, September 2005, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www