Walter Richard Sickert The Little Tea Party: Nina Hamnett and Roald Kristian 1915-16

Walter Richard Sickert,

The Little Tea Party: Nina Hamnett and Roald Kristian

1915-16

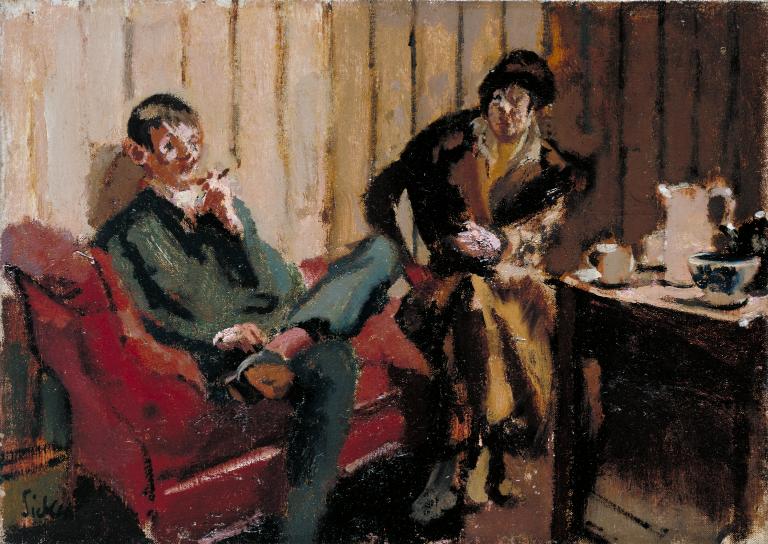

This cheerless double-portrait portrays the real, if ambiguous, relationship between the married artists Nina Hamnett – the ‘Queen’ of bohemian London – and Roald Kristian. The withdrawn Kristian sinks into the chaise-longue, leaning back against the striped panelling of the wall, ponderously smoking with legs crossed. Near him on the couch, but remaining isolated herself, Hamnett too smokes a cigarette and strikes a rather self-confident pose with hand on hip. She later wrote of the painting: ‘We looked the picture of gloom.’

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Little Tea Party: Nina Hamnett and Roald Kristian

1915–16

Oil paint on canvas

254 x 356 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Sickert’ in black paint bottom left

Purchased (Knapping Fund) 1941

N05288

1915–16

Oil paint on canvas

254 x 356 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Sickert’ in black paint bottom left

Purchased (Knapping Fund) 1941

N05288

Ownership history

Purchased by Sylvia Gosse from the Carfax Gallery, London, 1916; sold Christie’s, London, 11 December 1931 (45, as ‘A Tea Party’), bought by Jack Sampson; bought by Howard Bliss; Redfern Gallery, London, by 1941, where purchased by Tate Gallery.

Exhibition history

1916

Paintings by Walter Sickert, Carfax Gallery, London, November 1916 (4, as ‘Nina Hamnet and Roald Kristian’).

1926

Paintings by Walter Richard Sickert A.R.A., Savile Gallery, London, May–June 1926 (9, as ‘Nina Hamnett and Anr.’ [i.e. Another]).

1938

Paintings by Walter Richard Sickert, Arts Club of Chicago, January 1938 (21), Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh, February 1938 (27).

1941–2

Sickert, National Gallery, London, August–December 1941, Temple Newsam House, Leeds, January–March 1942 (38, as ‘The Little Tea Party – Nina Hamnett and Anr.’).

1942

The Tate Gallery’s Wartime Acquisitions, National Gallery, London, April–May 1942 (113, as ‘The Little Tea Party’).

1942–3

A Selection from the Tate Gallery’s Wartime Acquisitions, (Council for the Encouragement for Music and the Arts tour), Royal Exchange, London, July–August 1942, Cheltenham Art Gallery, September 1942, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, October 1942, Galleries of Birmingham Society of Arts, November–December 1942, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, January–February 1943, Victoria Art Gallery, Bath, February–March 1943, National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, March–April 1943, Manchester City Art Gallery, April–May 1943, Philharmonic Hall, Liverpool, May–June 1943, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh, June 1943, Glasgow Museum and Art Gallery, Kelvingrove, July 1943, Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne, August 1943 (75, as ‘The Little Tea Party’).

1945–6

Portraits and Portrait Groups, (Arts Council tour), Wildenstein, London, November–December 1945, Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery, December–January 1946, Middlesbrough Public Library, January–February 1946, University of Leeds, February–March 1946, Shipley Art Gallery, Gateshead, April 1946, Wakefield Museum and Art Gallery, May 1946, Worcester Public Library, Museum and Art Gallery, June–July 1946, Leicester City Museum and Art Gallery, July–August 1946, Harrogate Public Library and Art Gallery, September–October 1946, Guildford House, October–November 1946 (109, as ‘The Little Tea Party’).

1955

Spring Exhibition, Finsbury Art Group, Finsbury Town Hall, London, May 1955 (no catalogue found).

1968

L’Art en europe autour de 1918, British Council, L’Ancienne Douane, Strasbourg, May–September 1968 (230, reproduced).

1986

Nina Hamnett and her Circle, Michael Parkin Fine Art, London, October–November 1986, University of Hull, November–December 1986 (87).

1989–90

W.R. Sickert: Drawings and Paintings 1890–1942, Tate Gallery, Liverpool, March 1989–February 1990, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1990 (14, reproduced).

1992–3

Sickert: Paintings, Royal Academy, London, November 1992–February 1993, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, February–May 1993 (90, reproduced).

1996–7

Characters and Conversations: British Art 1900–1930, Tate Gallery, Liverpool, March 1996–April 1997 (34, reproduced on title page).

2004

Walter Richard Sickert: The Human Canvas, Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, July–October 2004 (31, reproduced).

2008

Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, Tate Britain, London, February–May 2008 (54, reproduced).

References

1932

Nina Hamnett, Laughing Torso: Reminiscences of Nina Hamnett, London 1932, pp.81–2.

1943

Lillian Browse and Reginald Howard Wilenski, Sickert, London 1943, pp.54–5, reproduced pl.45.

1957

Sickert: An Exhibition of Paintings, Drawings and Prints, exhibition catalogue, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield 1957, p.26.

1960

Lillian Browse, Sickert, London 1960, p.102.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, pp.633–4.

1971

Marjorie Lilly, Sickert: The Painter and his Circle, London 1971, p.89, reproduced pl.13.

1973

Wendy Baron, Sickert, London and New York 1973, p.156, no.363.

1976

Denys Sutton, Walter Sickert: A Biography, London 1976, p.189.

1986

Denise Hooker, Nina Hamnett: Queen of Bohemia, London 1986, p.90, reproduced.

1988

Richard Shone, Walter Sickert, Oxford 1988, p.67.

1988

Laura Wortely, British Impressionism: A Garden of Bright Images, London 1988, reproduced p.241.

1989

Elizabeth P. Richardson, A Bloomsbury Iconography, Winchester 1989, p.144.

1992

Bernard Denvir, ‘Advice from Mr. Sickert’, Artist, vol.107, no.12, December 1992, reproduced p.31.

2005

Matthew Sturgis, Walter Sickert: A Life, London 2005, p.482.

2006

Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, pp.105, 430, no.454, reproduced.

Technique and condition

Walter Sickert began this small sketch on a commercial pre-stretched fine plain-weave canvas purchased from the artists’ colourmen John B. Smith. The canvas has been prepared with an ‘absorbent ground’ that is probably either oil emulsion or tempera, providing a lean surface to paint on (see Tate N05092). A pink layer has been applied directly onto the primer and is visible in places, for example, under the figures and the table. It is applied quite thickly, but because it is largely covered, its extent is difficult to know. Sickert seems only to have used one pink as well as the white primer in this underlayer. He allowed this initial pink paint to dry then painted over in more subdued oil paint, pre-mixed on a palette in a narrow range of colours and tones. The underpainting is deliberately left visible at the surface; in some areas the pink undercolour shows through and in others pink and off-white primer or paint are exposed to act as the mid-tones of the painting.

There is some thick impasto corresponding to areas of detail and the figure shadows appear to be painted before the lighter parts then further modified with local shadow, possibly when still wet. There is some abrasion of the underlayers exposing the primer on the canvas tops, which indicate rubbing down after a change of mind or minor modification to the early image (see also Tate N03182). The brushmarks indicate a relatively lean paint, which is probably due to the absorbent ground, but there is also some richness and gloss in the shadows, perhaps limited to the final stages. Pin holes in each of the top two corners indicate that the painting may have been transported when wet or had something pinned onto it before it had dried, perhaps paper to transfer the sketch. The work has been recently revarnished following removal of an earlier discoloured varnish, which is not thought to have been applied by the artist.

Stephen Hackney

June 2004

How to cite

Stephen Hackney, 'Technique and Condition', June 2004, in Nicola Moorby, ‘The Little Tea Party: Nina Hamnett and Roald Kristian 1915–16 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, January 2005, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

The Little Tea Party is one of the last in a series of two figure interiors that had dominated Walter Sickert’s output from around 1910–15. Unlike the majority of his works from this period, the picture showcases the drama and tension of a real, rather than an imagined relationship, representing a portrait of the unusual association between the artist, Nina Hamnett (1890–1956), and her husband, Roald Kristian (born 1893).

Hamnett is now best remembered as the ‘Queen’ of bohemian London. During the 1930s and 1940s she was a well-known character in the pubs and bars of Fitzrovia, regaling fellow bohemians with stories and anecdotes in exchange for a drink. In 1932 she published reminiscences and anecdotes about her unusual life in an autobiography, Laughing Torso. The book caused a sensation and led to an action for libel being brought against her by Aleister Crowley, whom Hamnett claimed practised black magic. During the early twentieth century, however, Hamnett was a promising young artist, exhibiting her work with the Allied Artists’ Association, the New English Art Club and the London Group. Between 1917 and 1920 she taught classes at the Westminster School of Art on the recommendation of Sickert and Augustus John. Her talent, sociable nature and striking appearance made her a popular figure in avant-garde artistic society and brought her to the attention of some of the most significant artists of the day. Although her own work is now largely forgotten, she remains immortalised as the model for works by Roger Fry and Sickert. The title of her autobiography derived from a marble sculpture of her, Torso 1914, by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (1891–1915).

Hamnett’s friendship with Sickert dated from 1911 when she regularly frequented the Saturday afternoon ‘At Homes’ in Fitzroy Street, a habit which persisted until after the First World War. Sickert enjoyed her company, although his wife Christine found her boisterous spirits at parties rather wearing.1 Sickert’s letters to Hamnett are written in an avuncular tone and contain warnings against squandering her energy on parties instead of painting. He did, however, hold a high opinion of her work, writing in the Cambridge Magazine in 1918:

Nina Hamnett has shown at every stage of her rapid and somewhat turbulent development as a draughtsman and painter the possession of unmistakable power. An imperious instinct in the choice of her influences, a generous and frank surrender to such influences, and an almost indecent gluttony for work have placed her in a position that is, for an artist of her age, sufficiently brilliant, and to a critic of drawing and painting a tempting problem in hopes and fears.2

He described Hamnett as someone largely untouched by ‘doctrinaire ratiocinations’,3 and, unfortunately for Sickert, that meant she was also impervious to his own teachings. The elder artist, as was his wont, bombarded Hamnett with advice and information about painting which she largely ignored. She specialised in line drawings and portraits executed from life and did not favour Sickert’s prescribed method of working from squared-up drawings. Furthermore, Hamnett did not share Sickert’s motivation and drive, and she easily became distracted by the pleasures of society. In 1918 Sickert persuaded her to spend the summer working with him in Bath but she found the solitude of the quiet city isolating and depressing. She wrote to her other mentor and lover, Roger Fry, that Sickert ‘spends at least two hours daily at teatime in holding forth. I always say “yes” and go home and do the opposite.’4 Nevertheless, Hamnett greatly benefited from her association with Sickert and his circle although she perhaps preferred him as an entertaining host and raconteur than as a teacher and mentor. Her Portrait of Walter Sickert 1919 (private collection),5 depicts him as middle-aged but rakishly handsome, suavely dressed in a suit and bow-tie with his bowler hat at a jaunty angle, the ‘Louis Waller of the art schools’ as he was apparently known (Waller was a film star of the day).6 Hamnett also posed for Sickert on occasions, both clothed and nude, and her appearance is recorded in a drawing from around 1916.7 Her appearance, described by Sickert’s friend Marjorie Lilly as ‘an attractive little laughing face with an impertinent nose and a coltish yet graceful figure’,8 is less naturalistically but more evocatively depicted in The Little Tea Party: Nina Hamnett and Roald Kristian, a double-portrait of Hamnett with her husband.

The relationship captured by Sickert in The Little Tea Party was not a happy one. Hamnett remained legally married to the artist Edgar de Bergen for around forty years, while in actual fact their relationship only lasted about three years. The couple met in Paris in 1914 amid an exciting, artistic society that thrived in Montparnasse before the war and included members of the European avant-garde such as Constantin Brancusi, Amedeo Modigliani and Pablo Picasso. From the outset their relationship was characterised by a strange ambiguity and tension. In her autobiography, Hamnett later wrote:

The young man appeared to be a complete mystery. I was by this time desperately in love with him. Whether he liked me or not I have never been able to discover ... One afternoon Edgar said ‘How much does it cost to get married in England?’ and I said, ‘I think about seven-and-sixpence,’ and he said, ‘Let us get married!’ I said that I didn’t mind if I did ... After three weeks we got married [12 October 1914]. My Father paid the wedding licence. Everyone was very gloomy, including myself.9

The couple moved to Camden Town and continued to socialise with artists and European exiles in London. De Bergen, who claimed to be Norwegian, changed his name to Roald Kristian in order to sound less German. Both did some work for Fry’s Omega Workshops and de Bergen published a series of woodcuts in the Egoist. However, their mutual interest in art was not a sufficient basis with which to overcome their basic incompatibility, and their relationship gradually deteriorated. Hamnett complained of becoming ‘more and more bored with Edgar who was daily becoming more soulful, and spoke in parables which I had long since given up attempting to understand’.10 He reacted badly when she became pregnant and was uncaring when their baby was born two months premature and died. She, in turn, was merely relieved when, in 1917, her husband was imprisoned for three months’ hard labour for failing to register as a foreigner.11 On his release from prison de Bergen was deported back to France to fight with the Belgian army and Hamnett never saw him again.

Sickert’s painting captures much of the emotional strain of this unusual relationship. Husband and wife sit together in the corner of the room beside a table laid for tea. Hamnett recorded the sitting in her autobiography:

Walter, now Richard, Sickert lived in Fitzroy Street also, in fact he had a number of mysterious rooms for miles around as far as Camden Town. Edgar and I sat for him together, on an iron bedstead, with a tea-pot and a white basin on a table in front of us. We looked the picture of gloom.12

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Ennui c.1914

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1524 x 1124 mm; frame: 1741 x 1340 x 110 mm

Tate N03846

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1924

© Tate

Fig.1

Walter Richard Sickert

Ennui c.1914

Tate N03846

© Tate

Unlike the female model in Ennui, Hamnett’s stance is less passive and more confrontational. She maintains her equality with de Bergen by also smoking, holding the cigarette or cigar in her left hand while her right arm rests in a gesture of independence and slight belligerence on her hip. Her pose indicates her charismatic personality and unconventional lifestyle and she is the more domineering presence in the picture. Furthermore, the fact that she is wearing her outdoor coat and hat creates the impression that she has been induced to stay but may choose to leave at any moment.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Study for 'The Little Tea Party' 1915–16

Chalk on paper

support: 228 x 357 mm

Tate N05619

Purchased 1945

© Tate

Fig.2

Walter Richard Sickert

Study for 'The Little Tea Party' 1915–16

Tate N05619

© Tate

The location of the painting is Sickert’s studio at 8 Fitzroy Street, rooms which formerly belonged to James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Hamnett also used the studio on occasions to paint portraits when Sickert was out of town. Hamnett’s recollection in her 1932 autobiography that she and de Bergen posed for the picture on an ‘iron bedstead’ is at odds with the visual evidence of the painting and related preparatory drawings which clearly show the couple seated on a chaise-longue. This suggests that Hamnett conflated The Little Tea Party in her mind with Sickert’s more famous Camden Town Murder series in which the iron bedstead prominently featured. The painting shares the same predominance of dark shadows and black outlines, but the application of paint is less broken and looks towards Sickert’s later technique. An alternative possibility is that the composition of the painting is the result of a combination of preparatory sketches drawn on different occasions. In a study for The Little Tea Party (Huddersfield Art Gallery),14 Hamnett’s figure has been added on top of the drawing of de Bergen on the sofa (see Tate N05619). She was perhaps copied from another drawing in which she posed on a bed. The painting is unusual in that it depicts the tensions of a real relationship rather than one suggested by Sickert’s dramatic posing of Hubby, Marie and his other favourite models. Also, the presence of the male figure in this scene is diminished by the force of character of his female counterpart and is therefore devoid of the latent masculine menace of the Camden Town Murder pictures. The unhappy discomfort of the pair is mirrored by the shabby, grim nature of their surroundings, although in common with Sickert’s other interiors, it is a set-up staged within a studio. The chaise-longue, for example, features in other works, such as the drawing Woman Lying on a Couch c.1911 (University of Reading).15

The Little Tea Party was bought from the Carfax Gallery in 1916 by Sylvia Gosse (see Tate N04364), probably as a gesture of financial support for the artist. A later owner, Howard Bliss, the brother of the composer Sir Arthur Bliss, was a modest but important collector of largely contemporary art. He started collecting in the 1940s and in addition to Sickert, owned work by Louis le Brocquy, John Piper, John Craxton and Terry Frost. He was a friend and significant patron of the painter, Ivon Hitchens, amassing the most important collection of work by that artist.

Nicola Moorby

January 2005

Notes

Walter Sickert, ‘Nina Hamnett, Cambridge Magazine, 8 June 1918, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford and New York 2000, p.424.

Reproduced in The Painters of Camden Town 1905–1920, exhibition catalogue, Christie’s, London 1988 (13).

Nina Hamnett c.1916, pen and ink and pencil (private collection); Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.454.6; reproduced in Denise Hooker, Nina Hamnett: Queen of Bohemia, London 1986, p.105.

Walter Sickert, ‘A Well-Bred Artist’, in Nina Hamnett: A Catalogue of Paintings and Drawings, Eldar Gallery, London 1918, in Robins (ed.) 2000, p.423.

Related biographies

Related essays

Related catalogue entries

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘The Little Tea Party: Nina Hamnett and Roald Kristian 1915–16 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, January 2005, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www