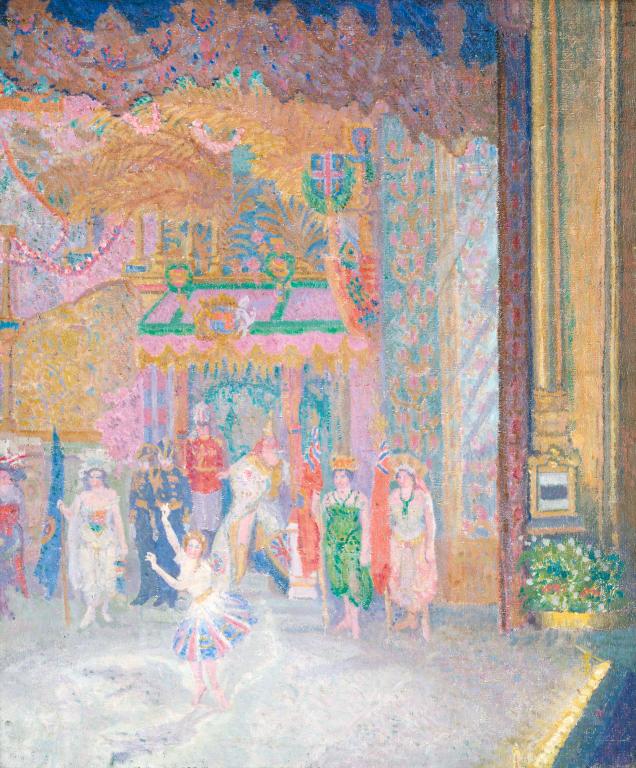

Spencer Gore Rule Britannia 1910

Spencer Gore,

Rule Britannia

1910

On stage at the Alhambra Theatre, the central figure of Gore’s painting, the Danish dancer Britta Petersen, performs the finale of the popular patriotic ballet Our Flag wearing a Union Jack tutu. The choreography included a pageant of England’s colonies. Gore’s vivid bright colours and spare use of outline emphasise the effect of the theatre’s stage lighting.

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Rule Britannia

1910

Oil paint on canvas

762 x 635 mm

Inscribed in unknown hand ‘Spencer F Gore Rule Britannia 19 Fitzroy Street’ on canvas stretcher

Purchased by the Patrons of British Art and presented through the Tate Gallery Foundation to the Tate Gallery 1992

T06521

1910

Oil paint on canvas

762 x 635 mm

Inscribed in unknown hand ‘Spencer F Gore Rule Britannia 19 Fitzroy Street’ on canvas stretcher

Purchased by the Patrons of British Art and presented through the Tate Gallery Foundation to the Tate Gallery 1992

T06521

Ownership history

Mrs Mary Johanna Gore, the artist’s widow; inherited by Frederick Gore and Elizabeth Cowie, the artist’s children, from whom purchased through the Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London, by the Patrons of British Art 1992 and presented through the Tate Gallery Foundation to Tate Gallery.

Exhibition history

1910

Forty-Third Exhibition of Modern Pictures by the New English Art Club, Galleries of the Royal Society of British Artists, London, Summer 1910 (204).

1911

Spencer Gore, Chenil Galleries, London, March–April 1911 (3).

1911–12

Loan Exhibition of Works Organised by the Contemporary Art Society, Manchester City Art Gallery, December 1911–January 1912 (57).

1912

Exhibition of Modern Pictures Organised by the Contemporary Art Society, Leicester Museum and Art Gallery, December 1912 (37).

1914

Twentieth Century Art: A Review of Modern Movements, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, May–June 1914 (417).

1951

The Camden Town Group, Southampton City Art Gallery, June–July 1951 (60, as ‘The Britannia Ballet (Alhambra Theatre)’).

1955

Exhibition of Painting & Sculpture by Some of the Artists who Visited the Café Royal 1900–’25, Café Royal, London, July 1955 (22, as ‘Britannia Ballet, Alhambra’).

1962

Spencer Gore and Frederick Gore, Redfern Gallery, London, February–March 1962 (27, as ‘The Britannia Ballet, the Alhambra’).

1970

Spencer Gore 1878–1914, The Minories, Colchester, March–April 1970, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, April 1970, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, May–June 1970 (28 as ‘The Britannia Ballet, the Alhambra’).

1980

Post-Impressionism: Cross-Currents in European Art, Royal Academy, London, November 1979–March 1980 (300, reproduced).

1983

Spencer Frederick Gore, 1878–1914, Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London, February–March 1983 (7, reproduced).

1987

Spencer Frederick Gore, Old Speech Room Gallery, Harrow School, Summer 1987 (20).

1988

British Modernist Art 1905–1930, Hirschl & Adler Galleries, New York, November 1987–January 1988 (22, reproduced).

2008

Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, Tate Britain, London, February–May 2008 (18, reproduced).

References

1914

Walter Sickert, ‘A Perfect Modern’, New Age, 9 April 1914, p.718.

1974

John Woodeson, ‘Spencer Gore’, Connoisseur, vol.185, no.745, March 1974, reproduced fig.1, as The Britannia Ballet at the Alhambra.

1980

Simon Watney, English Post-Impressionism, London 1980, p.37, reproduced pl.19.

1986

Claudio Zambianchi, ‘Appunti su Spencer Frederick Gore e la pittura inglese fra il 1908 e il 1910’, Storia dell’Arte, no.58, 1986, pp.282–3, reproduced fig.7.

1992

Tate Gallery Report 1990–92, London 1992, p.39, reproduced.

1994

‘Acquisitions 1990–1994 at the Tate Gallery I: The British Collection’, Burlington Magazine, vol.136, no.1098, September 1994, reproduced p.XVIII.

1998

Lucien Pissarro et le post-impressionnisme anglais, exhibition catalogue, Musée de Pontoise 1998, p.70.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.181.

2000

Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford and New York 2000, p.356, n.4, reproduced fig.25.

2001

Richard Humphreys, The Tate Britain Companion to British Art, London 2001, p.167, reproduced.

Technique and condition

Rule Britannia is painted in artists’ oil paints on primed stretched canvas. The image is painted over an earlier work that was obliterated by a coat of white priming or paint. This appears to have been applied before the paint had completely dried and therefore relatively soon after the first painting. Any discernible trace of the abandoned work is obscured by the white layer, which is opaque to x-radiography.

The canvas is a plain, slightly open-weave, hemp-like cloth with three cut edges and a selvedge along the right side. The cloth adjacent to the selvedge is reinforced with fine double-linen warp threads. It was originally attached with tacks to a weakly constructed stretcher, which provided inadequate support for the weight of the painted support. A thin glue sizing has been applied to the canvas and is visible in the interstices of the weave at the back. The evenly applied priming, below the earlier work, extends to the cut edges and stops just short of the selvedge. The double-priming is consistent with that found on other paintings by Gore, all of which appear to have been chosen for their particular properties (see also Tate N04675).

The canvas is a plain, slightly open-weave, hemp-like cloth with three cut edges and a selvedge along the right side. The cloth adjacent to the selvedge is reinforced with fine double-linen warp threads. It was originally attached with tacks to a weakly constructed stretcher, which provided inadequate support for the weight of the painted support. A thin glue sizing has been applied to the canvas and is visible in the interstices of the weave at the back. The evenly applied priming, below the earlier work, extends to the cut edges and stops just short of the selvedge. The double-priming is consistent with that found on other paintings by Gore, all of which appear to have been chosen for their particular properties (see also Tate N04675).

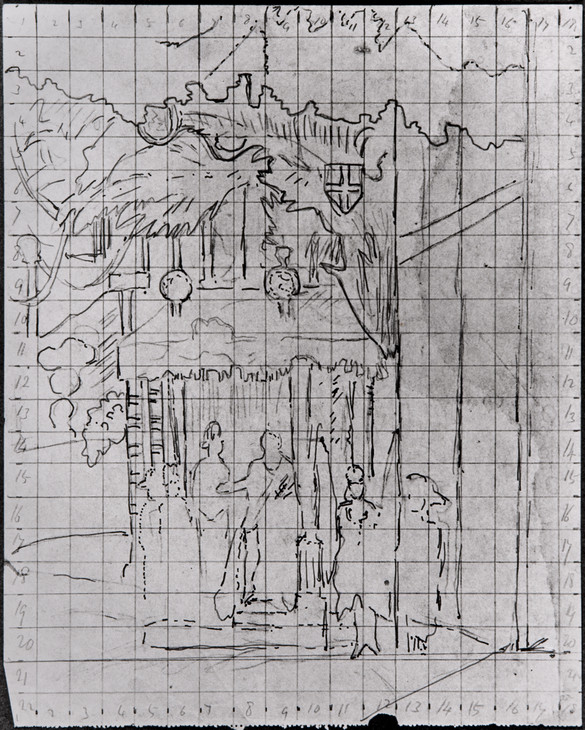

There are regularly spaced pencil marks with pin holes on all four tacking edges. Thin threads would have been strung from the pins to create a grid over the canvas to enable the transfer of the design from a squared-up drawing (see also Tate N05859). Neither the pins nor the threads remain but traces of the grid are clearly visible as fine ridges in the paint, which were made when the threads were pulled away from the wet paint surface. There is no visible preliminary drawing in pencil. The design was mapped out in paint (see also Tate T02260). The colours are predominantly opaque mixtures applied in a stiff consistency that has retained the brushmarks. Each colour is applied with a vigorous touch with minimum intermixing on the canvas and often leaving uncovered areas of broken white visible. This loose patchwork of vivid, contrasting colours in close, light tones conveys the overpowering strength of the multi-directional stage lighting that dissolves the solidity of forms on the stage. The sensation of light and movement is further enlivened by Gore’s confident use of a variety of handling and spare use of outlines in describing the scene. The painting is now unvarnished, as it is thought the artist originally intended. A crude handwritten inscription on the back of the original stretcher reads: ‘Spencer F Gore Rule Britannia 19 Fitzroy Street’.

Roy Perry and Sarah Morgan

June 2005

How to cite

Roy Perry and Sarah Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', June 2005, in Robert Upstone, ‘Rule Britannia 1910 by Spencer Gore’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background

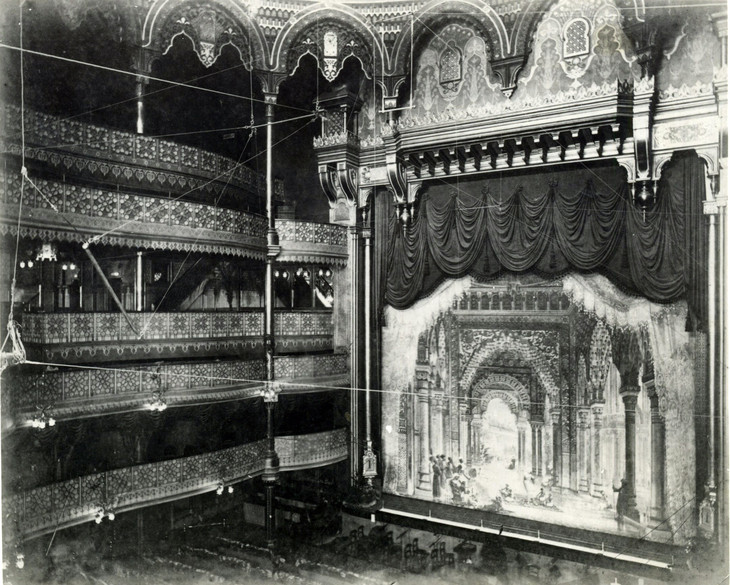

Gore was fascinated by the ballet, and in particular by the spectacular productions for which the Alhambra Theatre of Varieties in Leicester Square was famous (figs.1 and 2).1 The art critic Frank Rutter (1876–1937), one of his friends, recalled that the pictures which resulted from these visits were:

Magical paintings dancing with colour and movement, in which – unlike almost every other recent painter of ballets – Gore appeared to be absolutely unconscious that Degas had ever treated similar themes ... Degas, giant as he was, viewed the ballet with blasé, cynical eyes; Gore saw it quivering with wonder and delight. Never shall I forget going with him to Covent Garden when he saw the Russian Ballet for the first time. At the fall of the curtain he turned to me, his eyes shining with moisture, and whispered ‘I’ve often dreamt of such things – but I never thought I should see them!’2

The Alhambra Theatre of Varieties, Leicester Square, London c.1906

Colour-tint postcard

The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection

Photo © The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection / ArenaPal

Fig.1

The Alhambra Theatre of Varieties, Leicester Square, London c.1906

The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection

Photo © The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection / ArenaPal

The Interior of the Alhambra Theatre of Varieties, London 1897

Photographic print

The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection

Photo © The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection / ArenaPal

Fig.2

The Interior of the Alhambra Theatre of Varieties, London 1897

The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection

Photo © The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection / ArenaPal

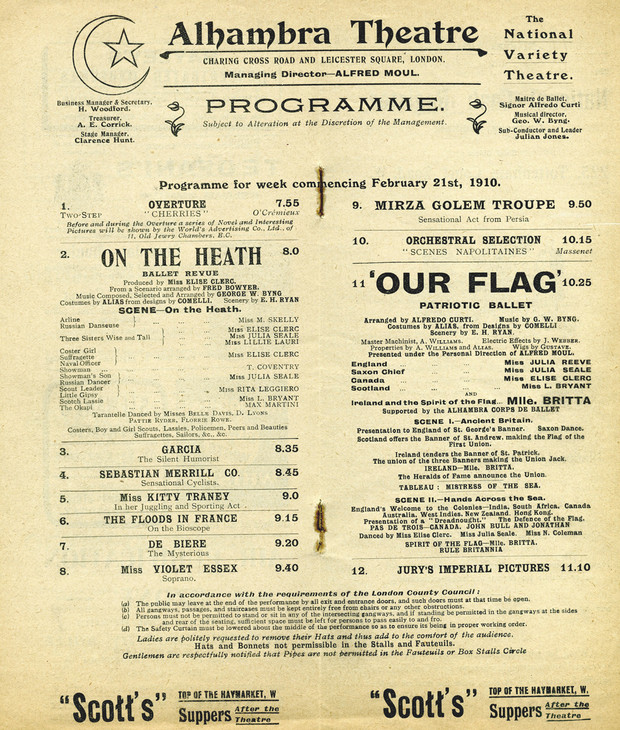

Rutter was writing about Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes company, which performed in England for the first time in 1911. Dating from the year before this, Rule Britannia depicts the finale of the patriotic ballet Our Flag, which opened at the Alhambra on 20 December 1909 (fig.3). It was immensely popular and ran for twenty-three weeks. The star of the show was the Danish ballerina Britta Petersen, whom Gore shows here in her Union Jack tutu performing the final dance, ‘Rule Britannia’ (fig.4). Generally known as ‘Mlle Britta’, Petersen had been imported by the Alhambra to compete with the success of her fellow Dane, Adelene Genée, who danced at the rival Empire Theatre of Varieties in Leicester Square. Born on 30 October 1888, Petersen enrolled at the ballet school of the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen in October 1899, and graduated in 1904. She started as a dancer in the theatre’s corps de ballet in 1906, and left on 6 April 1908, the year she premiered at the Alhambra.3 The Dancing Times in 1915 published Mlle Britta’s photograph and, in the past tense, perhaps referring to her death or retirement, described her as ‘a Danish danseuse, who achieved considerable success at the Alhambra, and also at the Coliseum, and who was one of the first to introduce classic dancing into South Africa’.4

Alhambra Programme for 'Our Flag' 21 February 1910

The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection

Photo © The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection / ArenaPal

Fig.3

Alhambra Programme for 'Our Flag' 21 February 1910

The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection

Photo © The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection / ArenaPal

The New Patriotic Ballet: Mlle. Britta as the Spirit of the Flag, in "Our Flag," at the Alhambra c.1909–10

Photographic print

The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection

Photo © The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection / ArenaPal

Fig.4

The New Patriotic Ballet: Mlle. Britta as the Spirit of the Flag, in "Our Flag," at the Alhambra c.1909–10

The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection

Photo © The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection / ArenaPal

The Sketch reported as early as 9 September 1908:

Mlle Petersen is to make her début as première danseuse at the Alhambra on a date not yet fixed. Like Mlle Genée, she is a Dane, and it is believed that she will be to the Alhambra what her countrywoman has been to the Empire. She has met with much success at the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen and at the Scala in the same city. If report be true, her engagement at the Alhambra is for five years.5

Mlle Britta’s first appearance at the Alhambra was in the ballet Paquita, which was added to the bill on 14 October 1908. She then went on to dance in their ballets On the Square, Les Cloches de Corneville, Psyche, On the Heath and Our Flag, all produced in 1909. The score for Our Flag was written by George Byng (c.1862–1932), the musical director of the theatre. Born in Dublin, Byng made his living in England initially as a violinist and conductor of the Mayfair Orchestra, but achieved great success as musical director of the Alhambra. Here he composed the music for some thirty ballets. The choreographer for Our Flag was Alfredo Curti, the Alhambra’s ‘Maitre de Ballet’, costumes were designed ‘by Alias from designs by Comelli’, and the scenery was by E.H. Ryan. The ballet was presented ‘under the Personal Direction’ of Alfred Moul, the Alhambra’s Managing Director.6

Our Flag

The first scene of the ballet was set in ‘Ancient Britain’, the action consisting of ‘Presentation to England of St George’s Banner. Saxon Dance. Scotland offers the Banner of St Andrew, making the Flag of the First Union. Ireland tenders the Banner of St Patrick. The union of the three Banners making the Union Jack. The Heralds of Fame announce the Union.’ There then followed an interval ‘tableau’ entitled ‘Mistress of the Sea’. Scene II was presented under the title ‘Hands across the Sea’, the narrative depicting:

England’s welcome to the Colonies – India, South Africa, Canada, Australia, West Indies, New Zealand, Hong Kong. Presentation of a ‘Dreadnought’. The Defence of the Flag. PAS DES TROIS – CANADA, JOHN BULL AND JONATHAN. THE SPIRIT OF THE FLAG ... RULE BRITANNIA.7

The Alhambra’s programme for the week commencing 30 May 1910 indicates that the ballet was scheduled to last thirty-five minutes. Typically, it was just one of nine very varied items on the evening bill for that week, which also included the conjurer Francois Rothig, ‘Charles Baron’s Burlesque Menagerie and Racing Cats’, ‘Lalla Selbini the Bathing Beauty’, the soprano Mlle Corona making her British debut, ‘Three Sisters Athletas, Parisian Equilibrists’ and a performance of Femina, the new Alhambra ballet to which Britta Petersen had by then been transferred to star in from Our Flag.

Petersen’s London debut in Paquita had been received slightly coolly by the anonymous critic writing in the Times:

Mlle. Britta is thoroughly accomplished (if she has a noticeable fault, it is that she fails to carry on the rhythm of movement in the pauses in her steps), and has a bright and pleasant manner that is attractive. Though we see in her no signs of the greatness that transforms technique into creation, she is a capable pantomimist, and genuinely deserves the position of leading dancer at such a house as this.8

A little over a year later, the reception the Times gave Our Flag was somewhat more positive, and described the narrative and effect of the ballet in some detail:

A ‘Rule Britannia’ motif, plenty of pretty faces and dresses, and Mlle. Britta’s graceful and rhythmical dancing are the chief features of the new patriotic ballet Our Flag, which was produced at the Alhambra last night. The ballet revue, On the Heath, still keeps its place at the end of the programme, but Our Flag, arranged by Alfredo Curti to the bright and tuneful music of G.W. Byng, makes an effective finish to the first part. There is not very much ‘story’ in the ballet. The opening scene, with a background of the waves that guard our native shores, is an elementary lesson in the composition of the Union Jack, and shows how, after England (Miss Julia Reeve), has been presented with St. George’s Banner, the flags of St. Andrew and St. Patrick are respectively ‘offered’ and ‘tendered’ (hardly the words that one would choose to express the actual historical facts) by Scotland and Ireland to complete the national ‘Jack.’ The second scene, described as ‘Hands Across the Sea,’ takes the form of a pageant of England’s colonial possessions, in which members of the corps de ballet representing India, South Africa, Canada, Australia, the West Indies, New Zealand, and Hong-kong, take part, and combine in a series of kaleidoscopic dances, with Mlle. Britta, Miss Elise Clerc, Miss Julia Seale, Miss Annie Mortimer, and Miss Julia Reeve as the principal figures. It is all very pretty and patriotic, and the appearance of the various colonies and the presentation of a miniature Dreadnought in front of a well-painted scene representing Windsor Castle stirred the audience to quite a little display of enthusiasm. But beyond the glitter and colour and movement of it all, and Mlle. Britta’s delightful dancing as Ireland and the Spirit of the Flag, there is nothing that particularly calls for remark, though the ballet, because of its briskness rather than its patriotic sentiment, was well received.9

Anglo–German relations

Evidently, the finale was a musical setting of the famous patriotic song ‘Rule Britannia’ (1740) by Dr Thomas Arne (1710–1778), using words by the poet James Thomson (1700–1748). The ballet itself was a symptom of the rising patriotic fervour which swept Britain between 1900 and 1914, and which reached a particular highpoint in 1909, the year Our Flag opened. This was a reaction to rising tensions in Anglo–German relations. Britain had been angered by German support of the Boers during the Boer War (1899–1902) and by Kaiser Wilhelm’s pursuit of colonies in Africa and elsewhere to rival the British Empire. For some decades in the nineteenth century Britain was the principal European manufacturer of consumer goods, but by the beginning of the new century Germany was now a significant rival. The Kaiser’s decision to double the size of the German navy led to a naval arms race with Britain, whose position of maritime supremacy was threatened for the first time since the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. Britain’s answer was to develop the Dreadnought battleship, the largest and most powerful warship the world had then known, and the first of which appeared in 1906. Such craft were viewed as the principal deterrent to invasion, and it is interesting to note the mention in the Times review of Our Flag the audience’s enthusiastic reaction to the appearance of a miniature Dreadnought in the show in front of a backdrop of Windsor Castle. The chorus of the song ‘Rule Britannia’ is specifically about Britain’s naval supremacy and its role in suppressing the tyranny of foreign invasion: ‘Rule Britannia! Britannia rule the waves. Britons never, never, never shall be slaves.’

Royal Artillery Band plays 'Rule Britannia' (recorded October 1899)

© Windyridge Music Hall CDs

When Gore painted Rule Britannia, fear of an imminent German invasion was rife, and it had formed the popular subject of novels such as The Riddle of the Sands (1903) by Erskine Childers, and The Invasion of England (1905) by William le Queux. Anxieties reached a frenzied level in 1909, when rumours, newspaper stories and parliamentary questions whipped up worries about invasion and espionage. Spurious sightings of Zeppelins were reported, and on 12 May 1909 the MP for Grimsby, Sir George Doughty, claimed that two ships full of German soldiers had sailed unchallenged in and out of the River Humber.10 On 19 May 1909 the MP for Frome asked the Secretary for War if he could confirm the rumour that 66,000 German soldiers were resident in southern England awaiting orders, and that a cache of rifles was awaiting them in London; the Secretary of War dismissed it as nonsense.11 Such stories were, however, given considerable popular credence, fed by a perception that Britain was losing the naval arms race with Germany. On 29 March 1909 the Government faced a vote of censure in the House of Commons alleging naval unpreparedness, although this was defeated. It was clear that Germany’s reaction to Britain’s Dreadnought programme was to construct battleships just as big, and it seemed that war was unavoidable.

Description and studies

In this picture, Gore emphasises the unusual, acidic colours cast by the stage lighting, contrasted with the dull light from the auditorium. The central figure of the ballerina casts a number of strangely shaped shadows on the stage. He painted another scene from Our Flag, entitled The Dance of the Spirit of Ireland 1910 (private collection),12 which also emphasises curious lighting effects. The viewpoint in this picture is taken from the balcony, which cuts diagonally across the bottom-left corner of the picture, a compositional device Gore was to use in other pictures of the music hall and theatre, for example Inez and Taki (Tate N05859) made the same year. Another oil which apparently also depicts Our Flag is The Alhambra Ballet 1910 (private collection).13 This work does not show the performers at all, but instead depicts the audience, with two figures on the balcony viewed from behind dominating the picture; but the many flags and bunting which characterised Our Flag are still visible beyond.

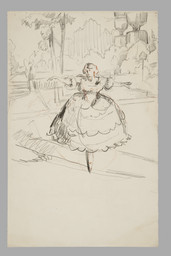

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Study for 'Rule Britannia' 1910

Private collection

Courtesy of the Gore family

Fig.5

Spencer Gore

Study for 'Rule Britannia' 1910

Private collection

Courtesy of the Gore family

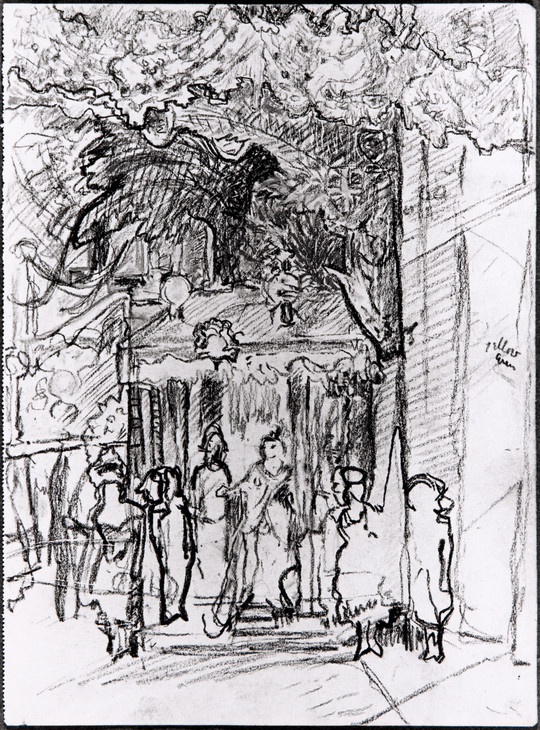

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Study for 'Rule Britannia' 1910

Private collection

Courtesy of the Gore family

Fig.6

Spencer Gore

Study for 'Rule Britannia' 1910

Private collection

Courtesy of the Gore family

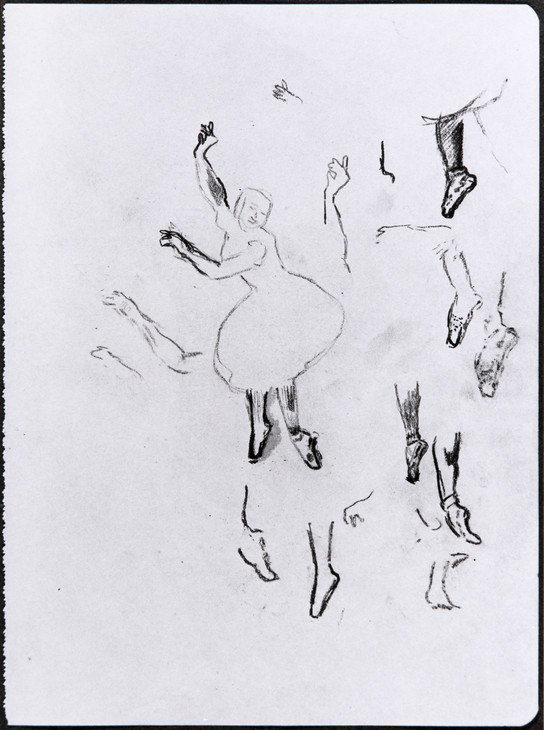

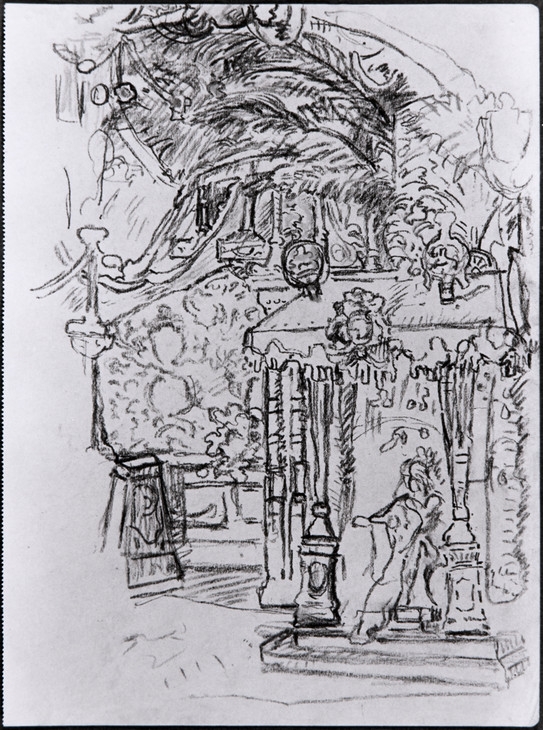

There are a number of preparatory drawings for Rule Britannia, all in private hands. One is a pencil and pen and ink line drawing for the whole composition, although without the figures of the central ballerina and the woman holding a flag at the extreme left. This has been squared-up and numbered in pencil (fig.5). The machine-serrated edge of the sheet indicates that it came from a notebook. Another drawing, more keenly worked and shaded in pencil, shows the overall composition, this time lacking only the figure of Britta Petersen. This has a colour note to the far edge which reads ‘pillar | green’ (fig.6). Another carefully depicts the ornate background (fig.7), and there are also studies of Mlle Britta herself (figs.8–9). Other preparatory material includes a sheet of three figure studies in pencil for the figures on the left of the composition: the woman who is bisected by the edge of the canvas is in this drawing unobstructed and annotated with several colour notes; the woman holding the blue flag, for whom there is a second outline study on the sheet directly below the more fully worked and detailed drawing; and the left-hand man in naval officer’s uniform wearing a cocked hat.

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Study for 'Rule Britannia' 1910

Private collection

Courtesy of the Gore family

Fig.7

Spencer Gore

Study for 'Rule Britannia' 1910

Private collection

Courtesy of the Gore family

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Study for 'Rule Britannia' 1910

Private collection

Courtesy of the Gore family

Fig.8

Spencer Gore

Study for 'Rule Britannia' 1910

Private collection

Courtesy of the Gore family

A further sheet has a pencil study of Britta Petersen, which shows her arms in two different positions, firstly as they are in the finished painting, except in reverse, with her right arm raised highest instead of her left, and secondly with her arms held out in front of her. The sheet also has studies for the arm and flag of the woman holding the blue flag to the left, and an outline sketch for the lower part of her body. In addition, there is a detailed line drawing of the upper part of the picture above the balcony, including the palm leaves and heraldic crests. These last three sheets are all the same size, and have the same machine-serrated edge and two rounded corners, showing that they came from the same note or pocket book. The existence of so many studies indicates the care with which Gore constructed the finished picture, with each element of the composition sketched and planned out.

Exhibition

Gore first exhibited Rule Britannia at the 1910 New English Art Club summer exhibition at the Royal Society of British Artists. But he and his friends felt a growing sense of the selectors’ disapproval. By November, writing of their recent showing, he wrote to his pupil John Doman Turner:

Your drawings looked very distinguished when they came up at the NEAC. Unfortunately the most conventional minded of a set of people whose ideas on painting are about 50 years out of date hung the watercolours of Rich!!!14 as you know from his work which is entirely imitative and has not an atom of observation in it ... Also you may notice that we – myself, Pissarro, Gilman, Bevan, Lamb have all been gently pushed into the inner rooms. Gilman had one thing rejected and Bevan two water colours while Innes another interesting artist has all his water colours very badly hung.15

This dissatisfaction with the NEAC went on to be one of the factors that precipitated the founding of the Camden Town Group in 1911. In his next letter to Doman Turner, Gore wrote:

As to where the things are hung it means nothing except that the NEAC dislike our kind of painting and will probably edge us out all together sooner or later and you have suffered with us.16

In his obituary of Gore, Sickert drew particular attention to Gore’s music-hall pictures and specifically recalled Rule Britannia:

Conder-like fancies, they had the resonance of reality, with all their grace as firmly established in its three dimensions as sculpture ... One picture represents the burlesque apotheosis of the end of an act where there are kings, and ‘principal boys,’ and officers in uniform and, conspicuously draped, a Union Jack which plays the leading role in the impression.17

Robert Upstone

May 2009

Notes

Frank Rutter, Some Contemporary Artists, London 1922, p.127. This book is dedicated to ‘S.F.G.’ [Spencer Frederick Gore] and ‘H.G.’ [Harold Gilman].

All information from an Alhambra programme in the collection of the Theatre Museum for the week commencing 30 May 1910.

Reproduced in The New English Art Club Centenary Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Christie’s, London 1986 (169), and Spencer Gore in Richmond, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Richmond 1996, p.15.

Reproduced in The Painters of Camden Town 1905–1920, exhibition catalogue, Christie’s, London 1988 (66).

Related biographies

Related essays

- Leisure Interiors in the Work of the Camden Town Group Jonathan Black, Fiona Fisher and Penny Sparke

- Empire and the City: Early Films of London Maurizio Cinquegrani

- Questions of Artistic Identity, Self-Fashioning and Social Referencing in the Work of the Camden Town Group Andrew Stephenson

- Slade School Influences on the Camden Town Group 1896–1910 Emma Chambers

Related catalogue entries

Related archive items

Related reviews and articles

- Walter Richard Sickert, ‘A Perfect Modern’ The New Age, 9 April 1914, p.718.

Related audio

-

Joseph Farrington performs 'The Union Jack of Old England' recorded 1914© Windyridge Music Hall CDs

-

William Paull performs 'In the King's Name Stand' recorded 1902© Windyridge Music Hall CDs

Related film

-

Performers at a theatrical garden party, including the comedians George Grossmith and Bobby Hales c.1910© British Pathé

How to cite

Robert Upstone, ‘Rule Britannia 1910 by Spencer Gore’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www