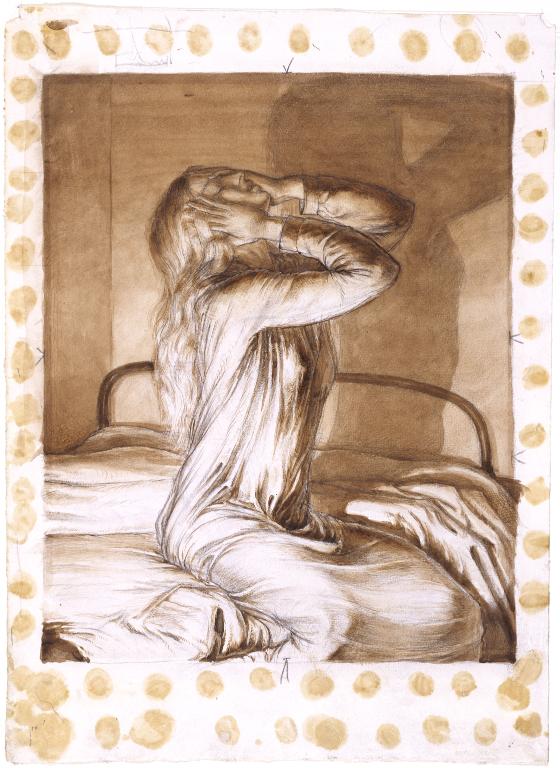

Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot Study of a Girl c.1910

Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot,

Study of a Girl

c.1910

This monochrome study in graphite washed with brown watercolour depicts the intimate setting of a bedroom at night. A woman enshrouded in the folds of a nightgown, long hair flowing loosely, cradles her upturned face in seeming anguish. Rendered in a heavy chiaroscuro leaving some white areas of the paper entirely blank, Lightfoot’s emotionally intense figure composition has more in common with European symbolists such as Pierre Puvis de Chavannes than his Camden Town Group contemporaries. This is a test.

Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot 1886–1911

Study of a Girl

c.1910

Graphite, ink and watercolour on paper

391 x 285 mm

Purchased (Duveen Drawings Fund) 1927

N04229

c.1910

Graphite, ink and watercolour on paper

391 x 285 mm

Purchased (Duveen Drawings Fund) 1927

N04229

Ownership history

... ; Albert Rutherston by 1921; purchased by Tate Gallery 1927.

Exhibition history

1921–7

Lent by Albert Rutherston to Tate Gallery, London 1921–7.

1944–5

Two Centuries of British Drawing from the Tate Gallery, (Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts tour), Bedford Public Library, September 1944, Lady Lever Gallery, Port Sunlight, September–October 1944, County Hall, Kendal, October 1944, Malvern Public Library, November 1944, Atkinson Art Gallery, Southport, January–February 1945, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, March–April 1945, Cathedral Refectory, Chester, April–May 1945, Harrogate Public Art Gallery, May–June 1945, Huddersfield Public Art Gallery, June–July 1945, Luton Public Museum, September 1945, Ferens Art Gallery, Hull, October–November 1945, Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery, November–December 1945 (43).

1951

The Camden Town Group: Festival of Britain Exhibition, (organised by Arts Council), Southampton Art Gallery, June–July 1951 (97).

1961–2

Drawings of the Camden Town Group, (Arts Council tour), Bradford City Art Gallery, October 1961, Southampton Art Gallery, November 1961, National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, December 1961, City Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham, January 1962, Arts Council Gallery, London, February–March 1962, Manchester City Art Gallery, March–April 1962 (75).

1969

The Camden Town Group, Cecil Higgins Art Gallery, Bedford, October–November 1969 (37).

References

1928

‘A Great Art Benefactor’, Studio, vol.95, 1928, reproduced p.84.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.1, London 1964, p.395.

1972

Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot 1886–1911, exhibition catalogue, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool 1972, no.37, pp.25–6.

Technique and condition

Study of a Girl is drawn with graphite and watercolour on wove paper. The paper is of good quality bearing a Whatman watermark in the top right-hand corner, visible from the reverse. It is of medium weight and retains its two deckle edges along the left and bottom sides, the remainder being cut. The image is drawn within a smaller rectangle positioned at the top centre of the sheet drawn with graphite and emphasised with watercolour. The monochrome study has first been applied in graphite and then washed with brown watercolour and a touch of red on the shoulder of the figure. Several test drawings and positioning marks have been made in pencil on the margin. There are also large circular brown spots along the edges that may appear to be the same brown watercolour but are in fact discoloured adhesive, relating to an historical method of mounting the drawing. The face of the support appears in good condition with only natural cockling in the areas where there is a heavier application of watercolour.

Tomoko Kawamura

November 2004

How to cite

Tomoko Kawamura, 'Technique and Condition', November 2004, in Nicola Moorby, ‘Study of a Girl c.1910 by Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot’, catalogue entry, May 2003, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background

Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot was one of the founder members of the Camden Town Group, but only exhibited at the first exhibition in June 1911. He was a recent, very talented, graduate from the Slade School of Fine Art and, with James Dickson Innes, was the youngest artist to be asked to join the group, probably invited by Spencer Gore. Unlike most of the other members, Lightfoot was not a pupil or follower of either Walter Sickert or of post-impressionism and, as an almost complete unknown, may only have been using the Camden Town Group platform as an opportunity to get his work exhibited in public rather than sharing in their overall aesthetic outlook. His work was wholly unlike anything else in the exhibition, a fact which was picked up by many reviewers who, although largely admiring of his work, were puzzled by his inclusion. Two paintings in particular from the four he exhibited, an oil, Boy with a Hoop. Frank c.1911 (fig.1), and another oil, in tondo format, Mother and Child c.1911 (private collection),1 were singled out for praise, especially by those critics who were uneasy with the bright colours and experimental style of Gore, Harold Gilman, Charles Ginner and Robert Bevan, or the sordid, murky interiors of Sickert’s Camden Town Murder paintings. The World went so far as to write that Lightfoot’s paintings alone were the ‘only contributions that have serious claim to be regarded as works of art’,2 and the Daily Telegraph maintained that his work ‘was assuredly the most interesting that the exhibition has to show’.3 The Morning Post described Lightfoot’s drawings as ‘powerful’, and suggested that this ‘William Orpen in the making’ was ‘not going to remain satisfied with the light, rather precarious, painting of the Camden Town Group’.4

This prediction proved to be correct. Not only was Lightfoot’s work stylistically and thematically very different to that produced by the other members of the Camden Town Group, but he had little respect or admiration for his fellow artists and their output. In a revealing letter to his Slade contemporary, Rudolph Ihlee (1883–1968), Lightfoot wrote:

The Camden Town Group are holding their exhibition at Carfax. It’s about the worst show I (have) ever seen in my life ... I suppose you know they drew me in to be a member of the Group, without my consent by the way. I have four things there – but I swear on my oath I will never show with the crowd again. It is 19 Fitzroy Street to the core. My stuff looks as much out of place and absurd as I do when I go to the Saturday afternoons lying competition at Sickert’s. They have had no money from me – and I’ll take it a good care they never will.5

He railed against the work of other members of the group, calling Henry Lamb ‘paltry’ and Augustus John ‘wild’. Gore’s work he condemned for being ‘as pretty as any young lady would wish to see – drawing, none – colour pretty – but not by any means good. He approaches as many schemes of colour in one picture as Whistler did in the whole of his lifework.’6 It probably came as no surprise to the other members, therefore, when Lightfoot resigned from the Camden Town Group after their first exhibition had closed.

During his time at the Slade, Lightfoot excelled in drawing from the figure, and throughout his brief career he continued to be interested in compositions of figure studies.7 Unlike the majority of his Camden Town contemporaries, who presented people as characters from everyday life or as a part of their overall concern with post-impressionist investigations into light and colour, Lightfoot maintained a more self-consciously graphic and literary approach. His interests lay in a preoccupation with draughtsmanship, line and form and an emotional response to his subject.

Subject and style

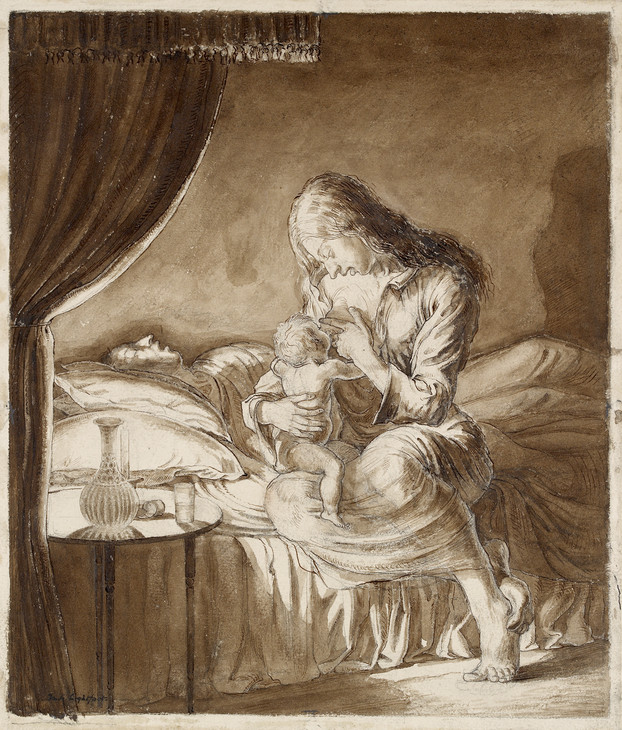

Study of a Girl is executed in pencil, pen and ink and brown watercolour on paper and shows a girl in a long nightgown seated on the edge of a bed holding her hands full length against either side of her upturned face. She could simply be awaking and stretching, but the looming shadow cast onto the wall behind her, disappearing off the edge of the picture frame, imbues the image with a sense of claustrophobia and mental anguish. Dark shadows, created in the folds of the bed linen and the girl’s nightgown, are portrayed through heavy washes of colour juxtaposed with white spaces where the paper has been left blank, combined with delicate line drawing in pencil or pen and ink. The tonal modelling of the drapery, streaming loose hair of the model and emotionally charged subject are perhaps an echo of the paintings of the French symbolist artist, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824–1898), whose work Arthur Clifton, the owner of the Carfax Gallery, recalled Lightfoot greatly admired.8 The pre-First World War generation at the Slade, which included artists like Stanley Spencer, Augustus John and William Orpen, were very influenced by the expressive and emotionally intense figure compositions of Puvis de Chavannes and other European symbolists. Lightfoot’s drawing seems to relate to that same artistic context which the art historian David Fraser Jenkins has called ‘Slade School Symbolism’: figure drawings based on life study which through emotive pose, dramatic lighting and often sexually charged imagery are expressive of an inner emotional existence and fundamental themes such as birth and death.9

Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot 1886–1911

Night Scene: Woman Feeding her Child c.1910

Pen and wash in brown ink over graphite on paper

311 x 265 mm

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Fig.2

Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot

Night Scene: Woman Feeding her Child c.1910

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Victor Hugo’s The Laughing Man

A separate set of illustrations with which Study of a Girl might be connected relate to a now lost drawing exhibited by Lightfoot at the 1910 Liverpool Autumn Exhibition, titled Dea (An Illustration to Victor Hugo’s ‘Laughing Man’). L’Homme qui rit or The Laughing Man was a melodramatic novel set in seventeenth-century England by the French author Victor Hugo (1802–1882). First published in 1869, it was translated into English in 1871 and remained a bestseller in England well into the twentieth century.14 It tells the story of Gwynplaine, an abandoned boy whose face has been deliberately deformed by a mysterious group called the ‘comprachicos’, so that he seems always to be laughing. He is brought up by an itinerant philosopher, Ursus, and his wolf companion, Homo, along with a blind girl named Dea whom Gwynplaine found as a baby, freezing in a snowstorm beside the body of her dead mother. Dea and Gwynplaine fall in love and travel around the country as mountebanks, earning a living as a freak show, ‘The Laughing Man’. One day, Gwynplaine is suddenly taken away by the authorities and it is revealed to him that he was sold and mutilated aged two on the orders of King James II and his true identity is heir to the title and lands of Lord Fermain Clancharlie. Turning his back on his wealth, peerage and intended duchess bride, Gwynplaine escapes and returns to Ursus, Homo and Dea who, believing he was dead, are embarking on a sea voyage. Gwynplaine finds the fragile Dea seriously ill as a result of his absence and they are joyfully reunited but, tragically, the shock of his return proves fatal to Dea and she dies in his arms. Gwynplaine is inconsolable, and, determined to follow her in death, ‘The Laughing Man’ kills himself by jumping overboard and drowning.

In the catalogue for the 1972 Walker Art Gallery exhibition, Gail Engert suggests that three other sepia works on paper, Woman with Staff Beckoning at Open Door to a Man Held Back by Woman and Old Man and Dog c.1910 (private collection),15 Woman Clasping Baby Lying Among Sand Dunes with Man in Far Distance c.1910 (Walker Art Gallery),16 and Man Taking Baby from Dead Woman in Dune Landscape c.1910 (private collection),17 might also be illustrations loosely based upon Hugo’s Laughing Man.18 The subject of the latter two images seems to be the point in the story where Gwynplaine finds and rescues the baby Dea, although Engert points out that there are discrepancies between the text and Lightfoot’s interpretation of it.19 For example, the scenes are set amidst sand dunes, not a snow-covered landscape, and the figure of Gwynplaine is older and not as horrifyingly ugly as suggested by Hugo. Tate’s Study of a Girl might be also derived from the story. The girl is possibly meant to be the figure of the beautiful, blind Dea at the point in the story where she believes her lover, Gwynplaine, to have disappeared forever. In the following passage Gwynplaine returns to find Dea, watched over by her anxious adopted father Ursus, lying feverish and dying while she laments the loss of her love:

She [Dea] had just raised herself up on the mattress. She had on a long white dress, carefully closed, and showing only the delicate form of her neck. The sleeves covered her arms, the folds her feet. The branch-like tracery of blue veins, hot and swollen with fever, were visible on her hands. She was shivering and rocking, rather than reeling, to and fro like a reed. The lantern threw up its glancing light on her beautiful face. Her loosened hair floated over her shoulders. No tears fell on her cheeks. In her eyes there was fire, and darkness. She was pale, with that paleness which is like the transparency of a divine life in an earthly face. Her fragile and exquisite form was, as it were, blended and interfused with the folds of her robe. She wavered like the flicker of a flame, while, at the same time, she was dwindling into a shadow.20

Several details from this passage appear to relate closely to the image, for example, Dea’s loose hair and long white dress which completely covers the body but yet clearly shows her female ‘exquisite form’ beneath the folds of the material. The text also contains a number of references to light and shadow which conforms with the evocative lighting, heavy chiaroscuro and ominous looming shadow cast behind the girl in Lightfoot’s picture. The mood of the image is one of unhappiness, foreboding and pain but the central figure is also oddly rapturous. The upturned face of the seated woman is highly reminiscent of the figure of Elizabeth Siddall in Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Beata Beatrix c.1864–70 (Tate N01279, fig.3), blending notions of ecstasy and death which are also present in Hugo’s text. One of the woman’s eyes is closed and the other is covered by her hand, which could be a pictorial device for demonstrating Dea’s blindness. The drawing is not an exact reflection of the text. In the story, this scene takes places on board a ship setting sail from a harbour, but Lightfoot has set the figure instead within a simple room. However, it has been suggested by Engert that Lightfoot’s illustrations are not faithful representations of the novel but invoke the spirit and sense of the tale. If Tate’s drawing is one of Lightfoot’s Hugo illustrations, then it cannot be connected with the three drawings first listed above, since their subjects are not matched in the novel.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti 1828–1882

Beata Beatrix c.1864–70

Oil paint on canvas

support: 864 x 660 mm; frame: 1212 x 1015 x 104 mm

Tate N01279

Presented by Georgiana, Baroness Mount-Temple in memory of her husband, Francis, Baron Mount-Temple 1889

Fig.3

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Beata Beatrix c.1864–70

Tate N01279

Ownership

The first known owner of this drawing was the artist Albert Rutherston (1881–1953), younger brother of William Rothenstein (1872–1945) and close friend of Spencer Gore. He trained at the Slade and was an exhibitor at the New English Art Club. As a member of the Fitzroy Street Group he would almost certainly have known Lightfoot personally.

Nicola Moorby

May 2003

Notes

Reproduced in The Painters of Camden Town 1905–1920, exhibition catalogue, Christie’s, London 1988 (88).

See Emma Chambers, ‘Slade Influences on the Camden Town Group, 1896–1910’, The Camden Town Group, Tate 2011, http://www.tate.org.uk .

David Fraser Jenkins, ‘Slade School Symbolists’, in The Last Romantics: The Romantic Tradition in British Art, Burne-Jones to Stanley Spencer, exhibition catalogue, Barbican Art Gallery, London 1989, p.71.

Walker Art Gallery WAG 7570. Reproduced in Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot 1886–1911, exhibition catalogue, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool 1972 (22, pl.8).

Related biographies

Related essays

Related reviews and articles

- Author unknown, ‘In the Picture Galleries. The Camden Town Group’ The World, 21 June 1911.

- Author unknown, ‘The Camden Town Group. Interesting Pictures’ Daily Telegraph, 22 June 1911, p.8.

- Author unknown, ‘The Camden Wonders’ Morning Post, 3 June 1911.

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Study of a Girl c.1910 by Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot’, catalogue entry, May 2003, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www