London’s Fashion Culture and the Camden Town Group Painters

Christopher Breward

The Camden Town painters’ fascination with the unpretentious and sometimes seedy aspects of modern life drew them away from the world of high fashion. Christopher Breward explores how Camden Town painters nonetheless responded to London’s fashion culture in their portraits and street scenes.

At first sight, the down-at-heel streets of turn-of-the-century north London that formed the setting for the formation of the Camden Town Group offer little inspiration to the dress historian seeking evidence of an engagement with themes of fashionability in the paintings of Walter Sickert, Spencer Gore, Charles Ginner and their associates. Camden’s plain-fronted housing stock and its broad but unexceptional main thoroughfare had been planned in the early nineteenth century as a service zone for the more prestigious aristocratic terraces of nearby Regent’s Park. The railway boom that followed the opening of Euston Station in 1838, rather than bringing prosperity, imposed a blight on the district that would endure almost to the end of the twentieth century. Residential and commercial property was threatened and obliterated by the building of lines leading to King’s Cross and St Pancras, and those large villas that did survive were broken up into lodging rooms for a transient population of building labourers and navvies. The canal system that bisected the rail tracks also created a grimy hinterland of wharves, warehouses, factories and stables that further disturbed any semblance of glamour or respectability. By 1913 the writer Compton Mackenzie was able to capitalise on the depressed reputation of the district in the lurid descriptions of inner-city seediness that pepper his novel Sinister Street:

When the cab had crossed the junction of the Euston Road with the Tottenham Court Road, unknown London with all its sly and labyrinthine romance lured his fancy onwards. Maples and Shoolbred’s, those outposts of shopping civilization, were left behind, and the Hampstead Road with a hint of roguery began ... Presently upon an iron railway bridge Michael read in giant letters the direction ‘Kentish Town’ behind a huge leprous hand pointing to the left. The hansom clattered through the murk beneath, past the dim people huddled upon the pavement, past a wheel-barrow and the obscene outlines of humanity chalked upon the arches of sweating brick ... A train roared over the bridge; a piano organ gargled its tune; a wagon load of iron girders drew near in a tintamar of slow progress ... He caught sight of a slop-shop where old clothes smothered the entrance with their mucid heaps and, just beyond, of three houses from whose surface the stucco was peeling in great scabs and the damp was oozing in livid arabesques and scrawls of verdigris.1

It was, however, precisely this atmosphere of banal degradation that attracted a generation of artists who sought in London’s inner suburban backwaters an alienating modernity equal to anything on offer in the competing capitals of continental Europe. In this spirit, Sickert had moved to Mornington Crescent in 1905, his choice of residence vindicating his friend William Rothenstein’s recollection that ‘Walter Sickert’s genius for discovering the dreariest house and the most forbidding rooms in which to work was a source of wonder and amusement to me. He himself was so fastidious in his person, in his manners, in the choice of his clothes; was he affecting a kind of dandyism “a rebours”?’2

Here then was a contradiction: the urbane dandy finding inspiration in the abject ennui of the everyday. Certainly the murder of part-time prostitute Emily Dimmock in St Paul’s Road, Camden Town, during the late summer of 1907 seemed to seal the notoriety of the district, arousing significant tabloid interest and providing Sickert with the subject matter of several canvases. The double life of the victim, who passed in the daytime as the law-abiding wife of a railway cook, and the fact that the main suspect in the case enjoyed an upstanding career as a commercial artist, heightened the bathos of a case that would find echoes in the subsequent arrest of patent medicine salesman Dr Crippen for the murder of his wife Cora, a retired music hall performer at their home in nearby Hilldrop Crescent in 1910.

In the popular imagination, Camden Town thus became intimately linked with the perversity and horror that seeped up from beneath the surfaces of contemporary urban life. But through the recording of these everyday scenes in the work of the Camden Town Group and their subsequent interpretation we are also able to reconcile the seemingly opposed positions of fashionable dandy and the chronicling of banality, producing a surprisingly radical reading of early twentieth-century popular and sartorial culture in the process. At second sight, in other words, Camden Town Group paintings offer a highly prescient insight into the changed nature of London’s fashion scenes in the early twentieth century.

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

The Café Royal 1911

Oil paint on canvas

support: 635 x 483 mm; frame: 878 x 725 x 100 mm

Tate N05050

Presented by Edward Le Bas 1939

© Tate

Fig.1

Charles Ginner

The Café Royal 1911

Tate N05050

© Tate

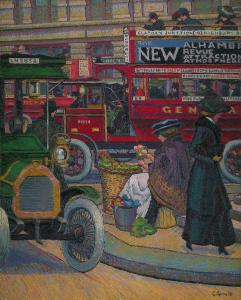

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Piccadilly Circus 1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 813 x 660 mm; frame: 939 x 786 x 65 mm

Tate T03096

Purchased 1980

© The estate of Charles Ginner

Fig.2

Charles Ginner

Piccadilly Circus 1912

Tate T03096

© The estate of Charles Ginner

Of course, not all Camden Town Group painters chose to limit their vision to the shabby rented rooms lining Camden High Street. Ginner, for example, in his paintings of The Café Royal (Tate N05050, fig.1) and Piccadilly Circus (Tate T03096, fig.2) of 1911 and 1912, evokes the festive atmosphere of metropolitan modernity that defined the West End of London as a newly confident space for sophisticated discourse and fashionable engagement. Here was a city of spruce clerks and emancipated stenographers, energetic New Women, elegant actresses, bohemians and dapper men-about-town in which the glittering and ever-changing surfaces of life marked London out as an enterprising locus for commerce and consumption. London writer Thomas Burke credited the change to the influence of Chicago and New York, noticing a ‘London that was going ahead. American ideas and ways of life had been infecting it for some time, and where it had been rich and fruity it was becoming slick and snappy.’3 Similarly, the fashion journalist Mrs E.T. Cook recorded both a growing addiction to the pursuit of shopping and a corresponding improvement in the built environment as she passed through the centre of town:

I am confident that if a million women of all classes could by any possibility be placed in a Palace of Truth, and interrogated straitly as to what they liked in all London, the vast majority of them would answer, ‘The Shops’. Indeed, you may easily ... find this out for yourself by simply taking a morning or afternoon walk down Oxford Street. Every shop of note will have its quota of would-be-buyers, trembling on the brink of irrevocable purchase; its treble, nay quadruple row of admiring females, who appear to find this by far the most attractive mode of getting through the day ... The shops of London have wonderfully improved in quite recent years; not perhaps so much in actual quality, as in arrangement and taste ... To dress a shop-front well was in the old days hardly considered a British trait ... Now even the Paris boulevard, that Paradise of good Americans, has, except perhaps in the matter of trees and wide streets, little to teach us. ‘The wealth of Ormus and of Ind’ that the shops of Regent Street and Bond Street display, their gold embroideries and wonderfully embroidered silks, tending to make a kleptomaniac out of the very elect, – these it would be hard to beat.4

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

The Dressmaking Factory c.1914

Oil paint on canvas

500 x 703 mm

Huddersfield Art Gallery

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © Huddersfield Art Gallery

Fig.3

Charles Ginner

The Dressmaking Factory c.1914

Huddersfield Art Gallery

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © Huddersfield Art Gallery

Nevertheless, though Ginner’s vision of fashionable urban modernity is generally a positive one, the tensions that underlay a supposed democratisation of glamour and the psychological hollowness that sometimes accompanied the drive to acquisition are captured in the nuanced portraits of working class north London women produced by other artists of the Camden Town Group.

Gore’s North London Girl (Tate T00027, fig.4) of c.1911–12 is an evocatively dispassionate record of the appearance and demeanor of the cleaner and charlady who serviced the studio in Fitzroy Street. Gore had stressed that ‘it’s not the business of the painter to dress his sitter to show his taste in dress, but to have them in clothes naturally characteristic of them’.6 Here the smartly trimmed bonnet, blue-frilled blouse and casually opened raincoat are a faithful rendering of a costume that is up-to-date but also resignedly in tune with the quieter patterns of local tastes and expectations.

Sickert’s L’Américaine (Tate N05090, fig.5), painted three years previously, makes a similar play on the apparent disconnect between the rhetoric of West End extravagance and more quotidian concerns. This coster-girl sports the wide straw boater (known colloquially as an ‘American Sailor’) that enjoyed popularity both as a flamboyant accessory of young East End working women and the badge of progressive liberal femininity adopted by the New Woman on her bicycle or the Suffragette at her protests. A typical example survives in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum (fig.6). In Sickert’s rendering, the outsized tilted hat and coy gesture of the sitter play simultaneously to standard representations of ‘cockney’ social types, the simpering actress pose of the Edwardian theatrical postcard and the presentational gesture of contemporary fashion advertising. The fractured nature of metropolitan subjectivity is thus suggested with great subtlety.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

L'Américaine 1908

Oil paint on canvas

support: 508 x 406 mm; frame: 748 x 649 x 55 mm

Tate N05090

Bequeathed by Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck 1940

© Tate

Fig.5

Walter Richard Sickert

L'Américaine 1908

Tate N05090

© Tate

Woolland Bros.

Hat c.1910

Straw trimmed with artificial flowers

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig.6

Woolland Bros.

Hat c.1910

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Men of all social ranks were no less affected by London’s evolving fashion scene. As the City developed to become the engine of imperialist expansion from the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the urban landscape came to be populated by those officials, administrators, clerks and tradesmen whose labour was necessary for the smooth running of the Empire, and their physical appearance is as evident in Camden Town Group paintings as the more obvious traces of feminine fashionability. Indeed, the quotidian and uniform presence of seemingly conservatively dressed working men was arguably even more representative of the rhythms of modern London life than the glamorous sheen of the West End café or shopping street.

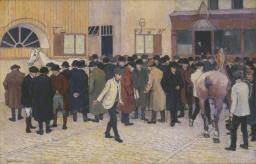

Robert Bevan 1865–1925

Horse Sale at the Barbican 1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 787 x 1219 mm; frame: 1090 x 1444 x 93 mm

Tate N04750

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1934

Fig.7

Robert Bevan

Horse Sale at the Barbican 1912

Tate N04750

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

The Artist's Wife 1913

Oil paint on canvas

support: 765 x 636 mm; frame: 918 x 790 x 80 mm

Tate T03561

Presented by Frederick Gore, the artist's son 1983

Fig.8

Spencer Gore

The Artist's Wife 1913

Tate T03561

Robert Bevan’s Horse Sale at the Barbican (Tate N04750, fig.7) of 1912, with its ranks of bowler-hatted and flat-capped bystanders, white-jacketed horse handlers and breeched equestrians, provides a remarkably variegated overview of the nuanced tones and values of masculine dressing. The location of the sale on the north-east side of the City afforded a more mixed clientele than the aristocratic business of Tattersall’s, London’s more famous horse auction house based in Knightsbridge. The proximity in Bevan’s painting of office boy and gent brings to mind Percy Fitzgerald’s description of East End ‘style’, published in his account of music hall culture of 1890:

The Eastender has created his idea [of fashion] from a gentleman or ‘gent’ of which he has had glimpses at the bars and finds it in perfection at his music hall. At the music hall, everyone is tinseled over; and we find a kind of racy gin-born affectation to be the mode, everyone being ‘dear boy’ or a ‘pal’ ... There is a suggestion of perpetual dress suit, with deep side pockets, in which the hands are ever plunged; indeed a true gentleman will rather hire his suit for the occasion – always costly and involving a deposit – rather than fail in these conveniences. And we must ever recollect to strut and stride rather than walk.7

The fascination of Camden Town Group artists with contemporary, largely working class, urban types is complemented by their more personal portrayals of wives, lovers and friends. These provided occasions for the rendering of a more bohemian style of dressing, completely at odds with the glitter of music hall costume or the humdrum practicality of working wardrobes.

Tate cataloguer Nicola Moorby notes that Gore’s 1913 portrait of his wife (Tate T03561, fig.8) shows her in

self-consciously aesthetic and avant-garde clothing. Her loose-fitting, thigh-length tunic reflects a vogue within Bohemian and artistic circles for Russian costume, made popular by the recent London performances of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Another distinguishing feature is her short bobbed hair, a style that didn’t become a mainstream fashion until after the First World War.8

Day dress c.1913

Ribbed silk and chiffon, trimmed with machine-made lace

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig.9

Day dress c.1913

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Jays Ltd

Evening dress c.1908

Satin, with silk panels embroidered with silver-gilt strip, coil, thread, spangles, pearls and diamantes, and trimmed with velvet, with boned bodice; net is modern replacement

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig.10

Jays Ltd

Evening dress c.1908

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Malcolm Drummond 1880–1945

Girl with Palmettes c.1914

Oil paint on canvas

support: 498 x 403 mm; frame: 489 x 591 x 44 mm

Tate T00893

Purchased 1966

© The estate of Malcolm Drummond

Fig.11

Malcolm Drummond

Girl with Palmettes c.1914

Tate T00893

© The estate of Malcolm Drummond

The Camden Town Group’s interest in this close relationship between the everyday surfaces of contemporary life, the avant-garde sensibility and the propensity of fashion culture and urban living to define notions of time, taste and place is further captured in Malcolm Drummond’s Girl with Palmettes of c.1914 (Tate T00893, fig.11). Here the strikingly direct gaze of the emancipated modern woman in her chic ensemble of soft broad-brimmed hat and stylishly trimmed, tailored suit seems to take us forward into the 1920s, to the democratic, open values of inter-war Britain.10

Notes

Cited in J. Richardson, Camden Town and Primrose Hill Past, Historical Publications, London 1991, pp.119–21.

Deborah Cherry and Jane Beckett (eds.), The Edwardian Era, exhibition catalogue, Barbican Art Gallery, London 1987, pp.71–3.

Quoted in Nicola Moorby, ‘North London Girl’, in Robert Upstone (ed.), Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, Tate Britain, London 2008, p.105.

Christopher Breward, Fashioning London: Clothing and the Modern Metropolis, Berg, Oxford 2004, pp.115–7.

Christopher Breward is Head of Research at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

How to cite

Christopher Breward, ‘London’s Fashion Culture and the Camden Town Group Painters’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www