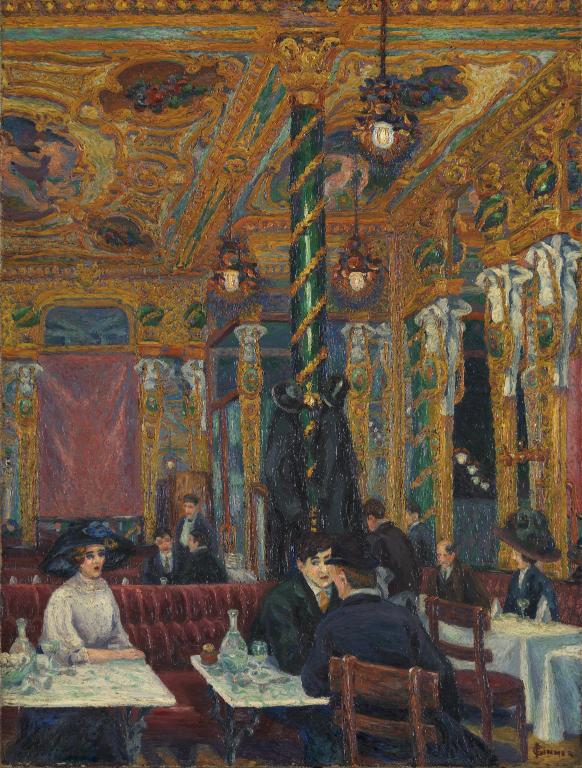

Charles Ginner The Café Royal 1911

Charles Ginner,

The Café Royal

1911

This painting depicts the fashionable Domino Room of the Café Royal on Regent Street, a meeting place for artists including the Camden Town Group and the vorticists. In the foreground, a woman turns to the conversation of two men on the right. The intense colours and consistent thickness of paint convey the opulence of the dining room’s gilded decoration, brimming with bright lights and mirrors.

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

The Café Royal

1911

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 483 mm

Inscribed ‘GINNER’ with the first letter a monogram of ICG (Isaac Charles Ginner) in brown oil paint bottom right; ‘Charles Ginner | 19 Fitzroy St. | Fitzroy Sq. | London N.W.’ in ink on lower member of stretcher.

Presented by Edward Le Bas 1939

N05050

1911

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 483 mm

Inscribed ‘GINNER’ with the first letter a monogram of ICG (Isaac Charles Ginner) in brown oil paint bottom right; ‘Charles Ginner | 19 Fitzroy St. | Fitzroy Sq. | London N.W.’ in ink on lower member of stretcher.

Presented by Edward Le Bas 1939

N05050

Ownership history

Donated by the artist to Allies’ Week Fund 1914; bought at Allies’ Week Fund sale, Brighton, [month unknown] 1914, 5 guineas (£5 5s) by Douglas Fox Pitt (1864–1922); bequeathed by him to his niece Patience Scott 1922; bequeathed by her to her husband Sir Henry Gisborne Holt (1864–1944) 1929; sold by him through the Redfern Gallery, London, for 18 guineas (£18 18s 0d) to Edward Le Bas 1937, by whom presented to Tate Gallery 1939.

Exhibition history

1911

Fitzroy Street Group display, 19 Fitzroy Street, London, early 1911.

1911

The London Salon of the Allied Artists’ Association, Royal Albert Hall, London, July 1911 (139).

1911

The Second Exhibition of the Camden Town Group, Carfax Gallery, London, December 1911 (29, as ‘The Café’).

1912

Société des Artistes Indépendants, Quai d’Orsay, Paris, March–May 1912 (1334, as ‘Le Café Royal, Londres’).

1914

Paintings, The Little Gallery, London, February 1914 (15).

1914

An Exhibition of Paintings by Harold Gilman and Charles Ginner, Goupil Gallery, London, April–May 1914 (22, £20).

1914

Cumberland Market Group display, 49 Cumberland Market, London 1914.

1938

Cross-Section of English Painting 1938, Wildenstein, London, March–April 1938 (22).

1939

The Camden Town Group, Redfern Gallery, London, March–April 1939 (7, reproduced).

1953–4

Charles Ginner 1878–1952, (Arts Council tour), Darlington Art Gallery, November 1953, Bristol Art Gallery, November–December 1953, Carlisle Art Gallery, January 1954, Tate Gallery, London, January–February 1954, Southampton Art Gallery, February–March 1954, Assembly House, Norwich, March–April 1954 (2, reproduced pl.2).

1998–9

An Ordinary Life: Camden Town Painters, Aberdeen Art Gallery, November 1998–January 1999 (13).

2006–7

El món d’Anglada-Camarasa, CaixaForum Barcelona, November 2006–March 2007, CaixaForum Palma, May–July 2007 (103, as ‘El Café Royal’, reproduced).

2008

Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, Tate Britain, London, February–May 2008 (20, reproduced).

2008–9

A Countryman in Town: Robert Bevan and the Cumberland Market Group, Southampton City Art Gallery, September–December 2008, Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, January–March 2009 (no number, reproduced pl.35).

References

1911

Frank Rutter, Sunday Times, 9 July 1911, p.4.

1911

Beatrix Terry, ‘As Others See Us’, Art News, 15 July 1911, p.75.

1911

James Bolivar Manson, ‘The Camden Town Group’, Outlook, 9 December 1911, p.824.

1914

‘Paintings by the Camden Town Group’, Athenæum, no.4504, 21 February 1914, p.281.

1933

Frank Rutter, Art in My Time, London 1933, p.153.

1951

Anthony Bertram, A Century of British Painting, 1851–1951, London 1951, reproduced pl.109.

1951

Hesketh Hubbard, A Hundred Years of British Painting 1851–1951, London and New York 1951, p.213, reproduced pl.71.

1952

Hubert Wellington, ‘Charles Ginner, 1878–1952’, Listener, vol.57, no.1195, 24 January 1952, p.143.

1952

John Rothenstein, Modern English Painters: Sickert to Smith, London 1952, p.192.

1955

Guy Deghy and Keith Waterhouse, Café Royal: Ninety Years of Bohemia, London 1955, p.129, reproduced opposite p.60.

1955

Denys Sutton, ‘The Camden Town Group’, Country Life Annual, 1955, pp.99–100.

1962

John Rothenstein, British Art Since 1900, London 1962, reproduced pl.22.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, pp.239–40, reproduced pl.38.

1970

Malcolm Easton, ‘Charles Ginner: Viewing and Finding’, Apollo, vol.91, no.97, March 1970, pp.205–6, reproduced fig.6.

1976

Wendy Baron, Camden Town Recalled, exhibition catalogue, Fine Art Society, London 1976, p.10.

1979

Charles Harrison, ‘The Camden Town Group’, Art Monthly, no.31, November 1979, p.8.

1979

Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, London 1979, pp.26, 231–3, 286, 371, reproduced pl.85.

1981

Andrew Causey and Richard Thomson (eds.), Harold Gilman 1876–1919, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, London 1981, pp.13, 26, 55, reproduced fig.4.

1988

Francis Farmar, The Painters of Camden Town 1905–1920, exhibition catalogue, Christie’s, London 1988, p.161.

1988

Hugh David, The Fitzrovians: A Portrait of Bohemian Society 1900–55, London 1988, p.107.

1996

Frances Spalding, The Dictionary of Art, London 1996, p.652.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, pp.36, 49, 146, 173, 175, reproduced pl.43.

Technique and condition

The Café Royal is painted in artists’ oil paint on primed stretched canvas. The support was supplied by Winsor & Newton Ltd, whose stamp and product number 388 marks the back of the canvas. The cloth is an ‘Artists’ Pure Flax [linen] Prepared Canvas; specially woven; a very coarse heavy canvas for large pictures boldly treated’.1 The painting’s dimensions indicate that the support was not purchased ready made but instead the artist bought the canvas from the roll, possibly primed it and cut and stretched it himself.2 The cloth would have cost Ginner twelve shillings per yard and as such was a more economical means of purchasing his materials, but it is also possible that he purchased it in this form so that he could experiment with materials. Ginner seems to have continued this practice throughout his career (see also Tate N05695).

No initial drawing remains visible beneath the substantial paint film. The paint is worked to a consistent thickness, creating a highly textured surface. The working of one colour wet into and over another is done so that they combine a little but do not coalesce sufficiently for the colours to become muddied or lose the distinct character of each application. The technique is particularly effective in conveying the opulence of the gilded decoration with its bright lights and mirrors. The rich swirls of saturated colours form an intricately worked surface of spiky impastos which scatter the light in a way reminiscent of the gilded surfaces themselves. Each form is defined with the same intensity with recession being achieved through perspective and the use of more detail in the foreground figures and table tops.

The vibrancy of the colours, employing contrasting complementary colours such as strident greens and crimsons, violets and yellows was maintained by saturating the surface of the painting, which may have ‘sunk’ with varnish. The thick paint has developed a few drying cracks and many areas of ragged brittle cracks in the top layers of paint, revealing the underlying colour in the apertures. These would have developed as the paint surface hardened or as a result of the varnish forming a brittle film on the surface before the paint had fully dried, and are a common feature of Ginner’s work (see also Tate T03096).

Roy Perry

June 2004

Notes

How to cite

Roy Perry, 'Technique and Condition', June 2004, in David Fraser Jenkins, ‘The Café Royal 1911 by Charles Ginner’, catalogue entry, May 2005, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

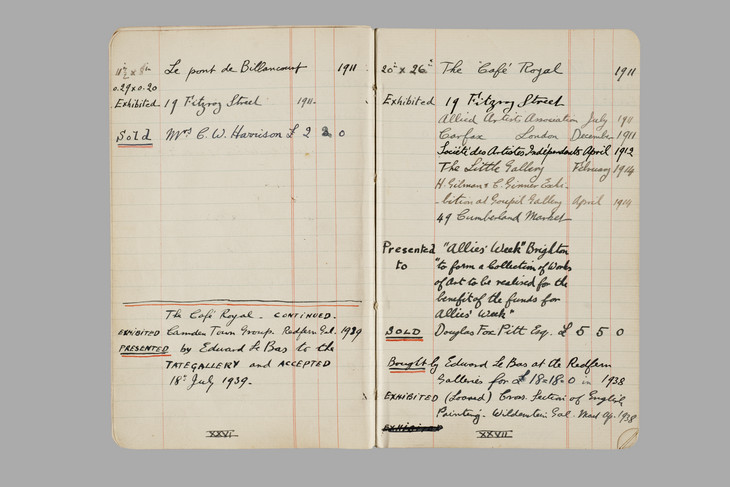

Background

Three central London scenes that Ginner painted soon after his move to the capital in 1910 belong to Tate: this work, Victoria Embankment Gardens 1912 (Tate T03841) and Piccadilly Circus 1912 (Tate T03096).1 Although Ginner’s fellow Camden Town Group colleagues often painted London streets and public places, they did not choose such glamorous and central locations, nor did they paint the city in a way that is so saturated in detail. The strong colours, lack of shading, thick paint, simple rectilinear designs and realistic content in Ginner’s paintings were highly unusual. As he completed his paintings, Ginner recorded details about them in a series of four notebooks now held in the Tate Archive (fig.1).2 These are the titles in date order of all the London pictures which he lists up until 1914, with owners added where known:

The Café Royal 1911 (Tate N05050)

Leicester Square 1912 (Brighton Museum and Art Gallery)3

Victoria Embankment Gardens 1912 (Tate T03841)

Piccadilly Circus 1912 (Tate T03096)

The Circus 1913 (Leeds City Art Gallery)4

London Bridge 1913 (Museum of London)5

The Sunlit Square, Victoria 1913 (Atkinson Art Gallery, Southport)6

The Angel, Islington 1913 (private collection)7

The Fruit Stall 1914 (Yale Center for British Art)8

The Tube Station, Kings Cross 1914 (whereabouts unknown)

Clerkenwell 1914 (whereabouts unknown)

Leicester Square 1912 (Brighton Museum and Art Gallery)3

Victoria Embankment Gardens 1912 (Tate T03841)

Piccadilly Circus 1912 (Tate T03096)

The Circus 1913 (Leeds City Art Gallery)4

London Bridge 1913 (Museum of London)5

The Sunlit Square, Victoria 1913 (Atkinson Art Gallery, Southport)6

The Angel, Islington 1913 (private collection)7

The Fruit Stall 1914 (Yale Center for British Art)8

The Tube Station, Kings Cross 1914 (whereabouts unknown)

Clerkenwell 1914 (whereabouts unknown)

Some of these locations follow Ginner’s addresses: after leaving his flat in Battersea he moved to Chesterfield Street (now Crestfield Street) near King’s Cross and he often visited his sister who lived in Islington. But most of the eleven pictures are of the most popular parts of central London, and as a group are unique. The paintings now look as if they were a series deliberately put together to cover the city centre, but this was not necessarily the case. Ginner did not show them together and was careful to choose a variety of subjects to exhibit at the Camden Town Group shows in 1911 and 1912. It was not until 1915 when the art critic Frank Rutter described some of the artist’s pictures of ‘the industrial cities of Yorkshire’ as an ‘historic series’ that any were taken as a survey of a particular place.9

A comparison between the appearance of these London scenes and the kind of pictures Ginner had made previously in France shows that there was little precedent. It was probably in 1910 that he began to make a record of his works in notebooks, but he included earlier pictures from 1908 when he could remember them. The titles of these early works reveal that he did not concentrate on town views at first. His London views generally correspond with his devotion to depictions of ordinary life, inspired by the work of Vincent van Gogh.10 From van Gogh, Ginner learnt to paint the common experience around him with a thick body of high-keyed colour. Ginner had seen a room of van Gogh’s paintings in the Bernheim collection in Paris in the early autumn of 1910,11 and in London later that year had seen his work in Roger Fry’s exhibition Manet and the Post-Impressionists.12 It is possible that a painting by Van Gogh, which belonged to two British collectors, was Ginner’s point of departure for The Café Royal. Alfred and Esther S. Sutro, he a playwright and she an artist, lent van Gogh’s Interior of a Restaurant (Restaurant Carrel à Arles, rue de la Cavalerie) 1888,13 to London exhibitions in 1908 and 1909.14 This café interior is a similar subject to The Café Royal: van Gogh also chose a drinker’s view, looking across the room towards customers seated at a distance, with bottles and carafes on tables. The example of the Dutch artist’s impasto technique is also evident.

There is one side of Ginner’s French work that is reflected in the design of his London pictures: his illustrations for magazines. In one of these illustrations, Les Suiveurs 1907,15 which depicts people in a public park, he drew a tree trunk densely covered with art nouveau patterns, showing his liking from the beginning for a saturated decoration of busy, concentric linear shapes. There is also a precedent for the subject of The Café Royal in his stylised drawing Scene at a Café Bar, with Two Women Seated at a Table in the Foreground Watching Dancers in Russian Costume 1909 (Victoria and Albert Museum, London),16 although the differences are also marked.

The Café Royal

According to Ginner’s records,17 he painted The Café Royal in 1911 and had taken it for sale to the open studio at 19 Fitzroy Street by July that year. The stretcher bears his name and this address, evidently added when he left the painting there. In the painting, the figures are either wearing coats or have hung them up, so the work was probably painted in early 1911 during the winter. Ginner’s view was from a seat in the ‘Brasserie’ or ‘Domino Room’ of the Café Royal, which was located on Regent Street near Piccadilly Circus. The room retained the original decoration from its opening in the 1860s with mirrors and red plush.

The café was a meeting place for French people and artists in London. A painting of the subject by William Orpen was described in 1915 as ‘Rendez-vous particulier des Français, où se réunissent nombre d’artistes’ (Special meeting place for the French, where many artists get together).18 Ginner was both French-born and an artist, and could find the French newspapers at the café. It was not an expensive place, although the drama critic Ashley Dukes remembered that his circle usually ate their dinner ‘in a chop house just behind the Café’, which did not have a licence for drinks, and then sat at the Café Royal for the evening with a ‘mazagran, coffee and milk mixture’ that cost four pence.19 The ‘painters of the general Chelsea or Camden Town Group sat in the part nearest Regent Street’, according to Dukes, and the circle of T.E. Hulme and the Vorticists sat at the back.20 The painting shows the drink tables at the front of the café, looking through to the section with tablecloths and napkins where people are dining.

Ginner shows a conversation between three people in the foreground. A woman on the left turns to speak to the man at the next table who has his chair turned slightly away from her, with another man sitting opposite him. It is a moment that might have been the subject of one of his Parisian illustrations.21 The people have not been identified, but in 1957, Marguerite Steen, the novelist and wife of William Nicholson, suggested that the man with his back to the viewer was the artist James Pryde, who did habitually wear a scarf and bowler hat in this fashion and was often in bars, though he is hardly recognisable here.22 This possible identification suggests that Ginner might have had contact with another network of artists including Pryde’s friends Orpen, Nicholson and Augustus John.23 The narrative in Ginner’s café is comparable to the modern conversation pictures with small figures in large interiors that were pioneered by Orpen.

William Orpen 1878–1931

The Café Royal 1912

Oil paint on canvas

1035 x 1035 mm

Musee d’Orsay, Paris

Photo © Musee d’Orsay, Paris, France / Giraudon / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.2

William Orpen

The Café Royal 1912

Musee d’Orsay, Paris

Photo © Musee d’Orsay, Paris, France / Giraudon / The Bridgeman Art Library

Adrian Allinson 1890–1959

The Café Royal 1915–16

Oil paint on canvas

102 x 127 cm

Private collection

© Estate of Adrian Allinson

Fig.3

Adrian Allinson

The Café Royal 1915–16

Private collection

© Estate of Adrian Allinson

The sudden vogue for painting the Second Empire-style interior of the Café Royal seems to have begun with Ginner, although it had been drawn in pastel by Sidney Starr back in 1888.24 The best known of the other depictions are by Orpen, 1912 (fig.2), Harold Gilman, 1912 (private collection),25 and Adrian Allinson, 1915–16 (fig.3). Allinson’s later work depicts a number of famous bohemians, including Allison himself, Dorelia and Augustus John, the art critic P.G. Konody, the writer Nancy Cunard and the artists’ model Iris Tree.26 In Orpen’s picture, which is twice the size of Ginner’s, the two figures talking in the foreground are certainly James Pryde and Augustus John, and others are recognisable as portraits. Pryde might therefore appear in both Orpen’s and Ginner’s paintings, as if they were different views of the same evening. But the interiors do not correspond exactly; the design of Orpen’s picture is much the same, making it seem a correction of Ginner’s, or at least a statement of difference. Gilman’s painting is of a similar size to Ginner’s and likewise depicts people talking, but Gilman took a view at an angle to the interior and used high-keyed colours to make a careful balance of space and reflections. The figures in the Orpen work are self-consciously composed as a group, as if they knew they were being observed; one of them, a wine waiter, stares out at the viewer. In the Gilman painting the figures are observed secretly as if unaware of the artist’s presence. Ginner took a half-way position, as it is clear that his subjects must have known they were being watched, but they carry on regardless.

Style and reception

Ginner’s oil study for this painting, of about one third of the size, differs slightly in detail but the composition is identical.27 The sketch includes a slightly larger area of the café; the woman at the left lacks her large hat, and there is one man fewer at the right. The colours are less intense in the sketch and the paint less thick, and there is not room for detailing odd effects like the ceiling lamps found in the larger version. Ginner habitually worked in his studio from drawings made in front of the subject, and the sketch may be a same-size copy as a drawing done on the spot. The perspective is a strict arrangement of verticals and orthogonals centred at a vanishing point towards the left, and was probably designed quite simply with a ruler. Critics have referred to Ginner’s training as an architect as encouraging his use of perspective, but this system is elementary. Many of the earliest records in Ginner’s notebooks are little pictures measuring 215 x 140 mm that he called ‘pochade’ (pocket size), which he presumably made as studies that he hoped to enlarge if he had the opportunity.

Although it was Gilman from among the artists of the Fitzroy Street Group who was closest to Ginner, both as an artist and as a friend, this picture is more indebted to Spencer Gore. It is possible that Ginner had learnt from the sophisticated architectural design of Gore’s music hall pictures, such as Rule Britannia 1910 (Tate T06521). In 1962 John Rothenstein, Director of the Tate Gallery and friend of Ginner, noted the firm structure of Ginner’s painting:

in The Café Royal, of 1911, there is ... the extremely complex yet entirely firm and logical construction, the mass of detail severely disciplined to the requirements of the design as a whole, that mark, though still more emphatically, the work of his later years.28

The Café Royal was singled out in a review of the 1911 Allied Artists’ Association exhibition in the Art News, the monthly magazine founded and edited by Frank Rutter. It was the longest description of any work in the show; the critic, Beatrix Terry, writing under the title ‘As Others See Us’, dealt with the work as if it were a decadent poem:

Charles Ginner shows a really fine painting of the Café Royal, a thing so charged with atmosphere and suggestiveness that one lingers there before it, rapt. In it Romance and Realism have settled their grievances, and kissed: for an effect of pure Romance is delineated with pure Realism. It has caught all the cross-currents of thought and emotion that breed, as familiar spirits, in that strange, exotic place, where all is theatrical and transient, and irrevocably futile. You feel that the air is heavy with fate, with decisive moments; here Destiny has tightened her web, chosen the halting place of lives. The people confront one another at the little tables; they lean forward, confidentially, bent upon the ‘momentary momentousness’ of their affairs; and the observer is impressed by beauty, as she laughs, defiant, in the clutch of the effete. Mr Ginner is not yet well known, but in this work he proves his capacity to spell Art with a capital A.29

With its provocative words and tone, this review suggests that the painting was thought to illustrate a slightly improper ease between the sexes.

Ownership

Ginner exhibited the picture regularly, presumably trying to sell it. In 1912 he sent it to the Salon des Indépendants in Paris and in 1914 sent it for display at Robert Bevan’s open studio at 49 Cumberland Market in Camden Town. Ginner gave the picture to a war charity in 1914.

The painting has belonged to two artists. The first owner was Douglas Fox Pitt, an amateur follower of the Camden Town Group (see Tate N03994). He also owned Ginner’s The Wet Street, Dieppe 1911 (private collection). The Café Royal was later bought by Edward Le Bas, who met Ginner in 1923 and became his principal patron and a friend.30 Rex Nan Kivell, Director of the Redfern Gallery, remembered the pair visiting the gallery in about 1938 and Le Bas buying the work.31 Le Bas was wealthy, and after beginning to buy pictures in 1936, following the death of his father, he eventually bought more of Ginner’s paintings than anyone else. He immediately gave this picture to the Tate Gallery, which then had only one painting by Ginner (Tate N03838). John Rothenstein, who was appointed director in 1938, admired Ginner’s work and quickly acquired several more of his paintings; it is possible that he arranged this gift from Le Bas.

David Fraser Jenkins

May 2005

Notes

Reproduced in Christie’s, London, 17 November 1978 (lot 24, as ‘The Fruit Stall’) and This Other Eden: Paintings from the Yale Center for British Art, exhibition catalogue, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven 1998 (74, as ‘Fruit Stall, King’s Cross’).

Charles Ginner, ‘Neo-Realism’, New Age, 1 January 1914, p.272. The visit is mentioned by Frank Rutter, implying that Ginner was already an admirer of Van Gogh, in Frank Rutter, ‘The Work of Harold Gilman and Spencer Gore: A Definitive Survey’, Studio, vol.101, no.456, March 1931, p.208.

J.B. de la Faille, L’Oeuvre de Vincent van Gogh: Catalogue raisonné, Paris and Brussels 1928, no.549. As Intorno di Ristorante, in Paolo Lacaldano (ed.), L’opera pittorica completa di Van Gogh, Milan 1977, no.538.

Anna Gruetzner Robins, Modern Art in Britain 1910–1914, exhibition catalogue, Barbican Art Gallery, London 1997, pp.120–1.

Description des Ouvrages de Peinture ... Offerts à la France par M. Edmund Davis, exhibition catalogue, Musée National du Luxembourg, Paris 1915, p.80.

Guy Deghy and Keith Waterhouse, Café Royal: Ninety Years of Bohemia, London 1955, p.129. See also Ashley Gibson, Postscript to Adventure, London 1930, p.30.

Reported by Ruby Ginner Dyer, the artist’s sister, letter to Mary Chamot, 11 August 1957, Tate Catalogue file.

Horace Brodzky’s recollections of the café mention Ginner as a frequent visitor, in The Café Royalists, exhibition catalogue, Parkin Gallery, London 1972.

At the Café Royal, pastel on canvas, 610 x 508 mm (private collection); reproduced in Degas, Sickert and Toulouse-Lautrec: London and Paris 1870–1910, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2005 (33).

Lent to National Museums and Galleries of Wales; reproduced in Harold Gilman 1876–1919, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, London 1981 (30).

A pictorial key of the people in Allinson’s painting is reproduced in Deghy and Waterhouse 1955, opposite p.96.

A study for ‘The Café Royal, 1911’, 305 x 205 mm (private collection, London); reproduced in Modern British Paintings 1880–2002, exhibition catalogue, Richard Green, London 2002 (22).

See Benjamin Fairfax Hall, Paintings by Harold Gilman and Charles Ginner in the Collection of Edward Le Bas, London 1965, and James Beechey, ‘Edward Le Bas’, Charleston Magazine, no.16, Autumn–Winter 1997, pp.37–43.

Related biographies

Related essays

- Leisure Interiors in the Work of the Camden Town Group Jonathan Black, Fiona Fisher and Penny Sparke

- London Narratives in Photography 1900–35 Valerie Williams

- Questions of Artistic Identity, Self-Fashioning and Social Referencing in the Work of the Camden Town Group Andrew Stephenson

- London’s Fashion Culture and the Camden Town Group Painters Christopher Breward

- Sex and the City: The Metropolitan New Woman Meaghan Clarke

Related reviews and articles

- Charles Ginner, ‘Neo-Realism’ The New Age, 1 January 1914, pp.271–2.

How to cite

David Fraser Jenkins, ‘The Café Royal 1911 by Charles Ginner’, catalogue entry, May 2005, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www