Charles Ginner Emergency Water Storage Tank 1942

Charles Ginner,

Emergency Water Storage Tank

1942

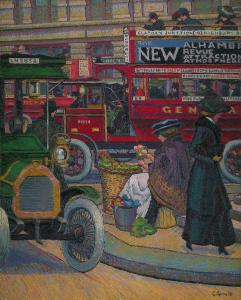

This painting was commissioned by the War Artists’ Advisory Committee in 1941. It shows the water tank at 222 Upper Thames Street that had a capacity of 55,000 gallons. Throughout the Blitz, the London Fire Brigade constructed such reservoirs by sealing the basements of bombed buildings in concrete. The dome of St Paul’s Cathedral, a symbol of the city’s resilience during the bombings, is visible at the painting’s upper left.

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Emergency Water Storage Tank

1942

Oil paint on canvas

686 x 508 mm

Inscribed ‘C. GINNER.’ in grey paint bottom right

Presented by the War Artists’ Advisory Committee 1946

N05695

1942

Oil paint on canvas

686 x 508 mm

Inscribed ‘C. GINNER.’ in grey paint bottom right

Presented by the War Artists’ Advisory Committee 1946

N05695

Ownership history

Commissioned from the artist for 25 guineas by the War Artists’ Advisory Committee 1941, by whom presented to Tate Gallery 1946.

Exhibition history

1942

Exhibition of War Pictures, National Gallery, London, October 1942.

1945

National War Pictures, Royal Academy, London, October–November 1945 (98).

1953–4

Charles Ginner 1878–1952, (Arts Council tour), Darlington Art Gallery, November 1953, Bristol Art Gallery, November–December 1953, Carlisle Art Gallery, January 1954, Tate Gallery, London, January–February 1954, Southampton Art Gallery, February–March 1954, Assembly House, Norwich, March–April 1954 (22, reproduced pl.3).

References

1942

Eric Newton, War Pictures at the National Gallery, London 1942, reproduced.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, p.241.

1971

Marjorie Lilly, Sickert: The Painter and his Circle, London 1971, reproduced pl.24.

1982

David Piper, Artists’ London, London 1982, p.145, reproduced p.144.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.175.

Technique and condition

Emergency Water Storage Tank is painted in artists’ oil paints on primed stretched canvas. The canvas bears no supplier mark but the stretcher is stamped ‘Made in England’. It is likely that the stretcher, which conforms to a standard commercial frame size, was purchased separately and that Ginner prepared his own support. The cloth is linen and has a fine plain weave with threads of uneven thickness in each direction. The canvas has been prepared with a glue size, which has formed a very thin glue layer. It has been primed with a thick opaque layer of lead white mixed with a small amount of chalk or gypsum and some additional extenders.1 A receipt from the artists’ colourman J. Bryce Smith Ltd. includes 6 ½ lbs of lead white, suggesting that Ginner was preparing his own canvases and may have done so, consistently or intermittently, throughout his career (see also Tate N05050). The prepared canvas provided a relatively smooth, finely grained surface on which to paint, which is quite different from that identified on earlier works (see also Tate T03841).

The composition appears to have been carefully drawn out although there is no visible evidence of initial drawing (see also Tate N05276). The technique is similar to that of Hartland Point from Boscastle (Tate N05306). It is painted in opaque mixtures of artists’ oil colours applied in short brushstrokes and dabs producing a busily textured surface with numerous lipped impastos. The lighter tints, such as in the sky, have a generally drier and more matt appearance than the more fluid darker colours that may have had painting medium added to them to retain their colour saturation. The density of paint, texture and finish are fairly consistent across the whole surface, although the sky, with its lack of detail built up in several layers, is less textured than the rest. Ginner appears to have been using good quality artists’ oil colours in tubes, probably adding medium to the colours on the palette (see also Tate T03096). His colours were generally classed as ‘Absolutely Permanent’ or ‘Permanent’ oil paints, ensuring ‘durability in the ages to come’.2

Roy Perry and Sarah Morgan

June 2006

Notes

How to cite

Roy Perry and Sarah Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', June 2006, in David Fraser Jenkins, ‘Emergency Water Storage Tank 1942 by Charles Ginner’, catalogue entry, May 2005, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

The London Fire Brigade constructed ‘emergency water supplies’ during the Second World War to supply water to their fire engines. There was a particular problem with water supply, both because the water mains were broken during bombing and because the river Thames is tidal and so at low tide it was difficult to pump water. From July 1938, in anticipation of war, new water pipes were constructed for London. By the beginning of the war ‘portable dams’, which held 1,000 gallons of water and were placed on open ground, were ready to be moved into threatened areas of the city. These were supplemented later by larger steel structures that held up to 5,000 gallons, sited in the middle of streets and kept full with water changed every month or so. In the event, both of these types of structure were of limited use as they were not large enough to provide water for more than a few minutes, being intended only as an immediate supply. London was bombed between September 1940 and May 1941. As buildings were destroyed, the water supply for the Fire Brigade was supplemented further by reservoirs built in the basements of bombed buildings and sealed in concrete. Although much larger than the tanks on the ground, these were also of only limited help. There are photographs of several of them among the records of the London Fire Brigade Museum, but neither of the books on the Fire Brigade during the Blitz mentions their use.1

The records of Ginner’s commission are at the Imperial War Museum.2 Ginner’s friend E.M.O’R. Dickey, Secretary at the Ministry of Information, wrote to the artist on 17 November 1941 asking if he would paint, as suggested by the War Artists’ Advisory Committee,

for a fee of 25 guineas, a bombed building adapted for storing water. The exact choice of subject and the size of the picture will be left to your own discretion. We thought that the adaptation of buildings which have been ‘blitzed’ to serve as water tanks, with the curious effect of reflections, would be a subject that would specially appeal to you, and we very much hope that you will take it on for us.3

Ginner accepted straight away, and wrote again on 11 December to ask if he could paint a building he had found himself, as he had not been sent a list. His own house in Pimlico had been damaged by a bomb (‘hardly habitable with the windows broken and boarded up’),4 and he was then staying with his patron the painter Edward Le Bas in Standon, Hertfordshire. The painting was finished by 4 March 1942, when Ginner again wrote, apologising that it had taken so long, ‘but for one thing it took me some time to find a subject where I could find a good place to do my studies from’.5 He went to see the picture displayed at the National Gallery in June 1942, and wrote that he was happy with the frame that had been chosen.6

The water tank depicted was at the building which was formerly 222 Upper Thames Street, between Boss Court and St Peter’s Churchyard in London.7 The building had been the offices of a firm of twine makers, Morrison, James and Son Ltd. The tank held 55,000 gallons, and it still existed, empty, in a photograph taken in 1957, although by then most of the building around it had collapsed.8 The dome of St Paul’s Cathedral is just visible in Ginner’s picture through a ruined window at the left. It had become a symbol of London’s survival of the Blitz, and it was characteristic of Ginner to include an important detail in such a marginal way. Already in 1921 he had cut off the top of St Paul’s in a view of Waterloo Bridge.9 He may have felt obliged to include reflections in the water, as Dickey had asked, and it is understandable that he found it difficult to find a water tank he could get close enough to draw. The scene looks oddly like a Roman bath, as Ginner included a little classical-style column at the right, which was presumably once part of the interior structure. The pre-war plan of this street is unrecognisable today.10

Ginner continued to paint other London subjects in the summer of 1942 when the Blitz was over, and arranged with Dickey that he should bring his drawings to be approved by the censor. He completed commissions for seven official paintings during the war. From the beginning he mentioned that he was short of money, and these commissions were evidently a help. He found the subjects congenial, and was punctilious in his replies to official correspondence. In November 1943 he passed to the Ministry of Information his invoice from J. Bryce Smith Ltd for paints that he used on a later commission to record some barges carrying concrete. The total amount was £1 13s 8d, and in addition to 15 shillings for flake white the eight colours were cobalt, chrome yellow, viridian, new blue,11 burnt sienna, raw sienna, Paynes grey and chrome orange. His friend Marjorie Lilly remembered that despite being short of money Ginner was always extravagant in his use of pigments.12

Ginner was elected an Associate Royal Academician in 1942, but was evidently still faithful to the Camden Town Group, as he replied on 4 May to congratulations from Dickey: ‘I have made a long journey from Camden Town to Piccadilly, but I hope that in the R.A. I shall still prove myself worthy of the Camden Town Group.’13 This is likely to be the last such proclamation of artistic faith made by an original member of the group. It may have been in Ginner’s mind because Walter Sickert had died in January 1942, leaving only him and the elderly Lucien Pissarro still alive from the original core group.

Ginner was one of the few artists to have been commissioned to paint in both World Wars; in 1917–18 he had made a huge painting of a shell-filling factory in Hereford for the Canadian War Records.14 The fee for this commission was £350, by far the largest payment Ginner ever received, which may have encouraged his interest in official commissions during the Second World War.15

Emergency Water Storage Tank is recorded in the artist’s third notebook as Bombed Building for Storing Water, with a note that it was exhibited at the National Gallery in 1942.16

David Fraser Jenkins

May 2005

Notes

Information from Esther Mann, London Fire Brigade Museum. The books are Neil Wallington, Firemen at War: The Work of London’s Fire-fighters in the Second World War, London 1981, pp.41–2, and Sally Holloway, Courage High! A History of Firefighting in London, London 1992, p.181.

London Fire Brigade, letter to John Hayes, Assistant Keeper at the Tate Gallery, 2 September 1957, Tate Catalogue file.

Recorded in his notebooks, Tate Archive TGA 9319/3, p.47, 37 x 48 inches. Sold to T.W. Spurr probably in the 1930s. Reproduced in Gerrard Gwathmey, ‘A Group of English Art Rebels’, Arts and Decoration, August 1922, p.253.

‘The honest un-made-up commercial buildings are now nearly all gone’, Nikolaus Pevsner and Bridget Cherry, London, vol.1, London 1996, p.297.

‘No.14 Filling Factory Hereford, 1918, 12 ft by 10 ft’, recorded in Ginner’s first notebook, Tate Archive TGA 9319/1, p.CXX. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, no.8173, 305 x 366 cm.

Two other Second World War oil paintings by Ginner are in the collection of the Imperial War Museum, Building a Battleship 1940 (IWM ART LD 252) and Machine-Tools for Russia 1942 (IWM ART LD 2809), reproduced at http://www.iwmcollections.org.uk/ .

Related biographies

Related catalogue entries

Related reviews and articles

- Charles Ginner, ‘Neo-Realism’ The New Age, 1 January 1914, pp.271–2.

How to cite

David Fraser Jenkins, ‘Emergency Water Storage Tank 1942 by Charles Ginner’, catalogue entry, May 2005, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www