Questions of Artistic Identity, Self-Fashioning and Social Referencing in the Work of the Camden Town Group

Andrew Stephenson

The image of the artist and of artistic groups was an important element in the formation of the public identity of the Camden Town Group. Andrew Stephenson considers the function of portraits and depictions of artistic settings in creating an identity for the group in tune with its experience of modernity.

Between c.1905–14, as British artists became increasingly active in the presentation and publicity of their work, so artists’ exhibiting societies and small groups of like-minded individuals such as the Camden Town Group assumed a new prominence.1 The Fitzroy Street Group (founded in 1907), the Allied Artists’ Association (1908), the London Group (1913) and the Cumberland Market Group (1914), like the Camden Town Group, sought increased group visibility and greater autonomy in the exhibition, publicity and sale of their work.2 As Walter Sickert, a founder member of each of these save the Cumberland Market Group, argued, ‘these things are done in gangs, not by individuals’.3

For some critics the promotion of such collective entrepreneurial ideals was a detrimental development, since the ‘subdivision of the art world into small cliques’ meant ‘each group of workers forms a little mutual admiration society with its own small class of patrons and its advocates retained to push its claims for attention in the press’.4 Nevertheless, for many artists such cooperative commercial formations were seen as crucial to managing the business conditions of the marketplace by attracting publicity and thereby staking a viable claim to the international membership of the artistic avant-garde. By creating ‘Little Pictures for Little Patrons’,5 Sickert was clear that the main reason for the Fitzroy Street Group’s informal Saturday ‘At Home’ gatherings was commercial: ‘we all have work for sale at prices that people of moderate means could afford’.6

Through a close examination of Camden Town Group self-portraits and portraits of artists, and the representations of artists’ studios, art galleries and London socialising venues, this essay demonstrates how late nineteenth-century conventions of artistic (self-) presentation, especially those promoting the artist-dandy and all-male avant-garde affiliations, had to be carefully revised in the first two decades of the twentieth century. One reason for this shift was the need to counter conservative accusations following the Oscar Wilde trials in 1895 that single-sex bohemian art groups encouraged homosocial camaraderie and promoted an un-English exhibitionist pose that was increasingly seen as morally troubling and sexually suspect.7 By establishing the Camden Town Group as an all-male fraternity the members were open to such suspicions, fuelled by their intense and communal male bonding and intimate ‘Tête-à-têtes with someone who is a comrade’.8 When Sickert declared that ‘the Camden Town Group is a male club, & women are not eligible. There are lots of 2 sex clubs, & several one sex clubs, & this is one of them’,9 he was emphatically aligning the group as artist-bohemians with a virile, all-male lineage by employing the militant rhetoric of sexual discrimination, one that the art historian Lisa Tickner has recognised not only marginalised women’s contributions but claimed that the real business of modernism was distinctively and exclusively ‘men’s work’.10

Another reason for this revision was the need to counter the rising nationalism and racism evident in English art writing after c.1905, which increasingly called for a distinctively English art reflecting the changes occurring within the modernisation of the national culture.11 This essay demonstrates how during these years the serviceability of previous models available for modern self-portraits or updated portraits was revised by the Camden Town Group artists in order to distance themselves from earlier Francophile and Whistlerian aesthete allegiances. As conservative English critics demanded distinctively anglicised and more resolutely manly configurations of artistic avant-gardism rooted in localised social and sexual experience, so Sickert and other Camden Town Group artists deployed references drawn from the vibrant working and lower middle class cultures of Camden Town. These were understood by expanding English art audiences with eclectic cultural tastes to configure a differently constructed form of artistic cosmopolitanism. One that was premised on London’s distinctive commercial and cultural resources and its particular social and sexual relationships, which espoused its own forms of national and imperial modernity in an effort to attract allies, patrons, audiences, critics and publicity at home and abroad.

My historical starting point for this investigation is February 1905, when Sickert travelled to London from Dieppe, which had been his primary place of residence from the winter of 1898. Sickert returned to see the extensive Memorial Exhibition of the Works of the Late James McNeill Whistler at the New Gallery, comprised of over 750 works, and to sell some pictures by Whistler which he owned. During his time in Dieppe he had largely abandoned portraiture, asserting ‘I see my line. Not portraits’,12 and when on extended visits to Venice he had executed only a few.13

However, after 1905 Sickert decided to make London his main residence, encouraged by his close friendships with William and Albert Rothenstein and Spencer Gore. He acquired two studios, one at 76 Charlotte Street and another at 8 Fitzroy Street. In the following October he also took lodgings at 6 Mornington Crescent in Camden Town.14 In London, Sickert started a series of portraits including that of Jacques-Émile Blanche, c.1910 (Tate N04912, fig.8). He completed two self-portraits – The Juvenile Lead (Self-Portrait) 1907 (fig.6) and Self-Portrait: The Painter in his Studio 1907 (fig.7) – as well as a studio interior with female figure, The Studio: The Painting of a Nude c.1906 (private collection).15 A small group of later self-portraits and portraits of artists dating from c.1912–14 include Sickert’s own Self-Portrait: The Bust of Tom Sayers 1913 (fig.28). Between c.1905–14, although Sickert resumed portraiture, including portraits of other artists in interiors, only a few of these works were commissioned and, therefore, must have been intended for exhibition and the commercial art market.

This kind of self-portraiture and depictions of artistic friends and their milieu provided a privileged insight into British artists’ lifestyle for a contemporary audience. Such self-presentation demanded careful staging and imaginative reinvention in an increasingly cosmopolitan London art world composed of expanding, socially diverse and knowledgeable audiences.

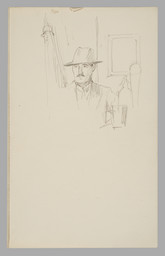

Malcolm Drummond 1880–1945

Charles Ginner 1911

Oil paint on canvas

603 x 490 mm

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.1

Malcolm Drummond

Charles Ginner 1911

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

In spite of this, there was a need to avoid a sense of naked commercialism, since, as Sickert acknowledged in a 1910 article in the Art News, portraiture has ‘a useful and honourable place in a world of supply and demand’.18 Moreover, painters knew that portraiture was equally susceptible to the challenges and business structures emerging in publishing, photography and the mass media, which would complicate, and even trivialise, the validity of its claims for elevated aesthetic status. Sickert declared that ‘The task of the fashionable portrait painter, the painter of the femme du monde (‘Comme si nous n’étions pas tous du monde,’ as I once heard Degas say) ... has been somewhat simplified of late by the very able draughtsmen who illustrate the advertisements of our great dry-goods stores’.19 For Sickert it was crucial to understand how the critical and commercial reception of modern portraiture across international art markets inflected changing national priorities, localised issues and shifting social and moral concerns.

‘Anglicising’ artistic self-portraiture

Writing in June 1910, Sickert recognised that English artists in the late Victorian and Edwardian period had worked hard to update older, conservative forms of portraiture by frequently employing powerful models and updated pictorial languages from continental Europe. He recorded: ‘How far we have travelled in our ideals of portraiture! ... Alas! Now we are all cosmopolitanised.’20

Throughout the late 1880s and 1890s, Sickert himself had undertaken a similar exercise. He produced a number of self-portraits and portraits of fellow artists and art writers, many of which were exhibited at the New English Art Club (NEAC) from 1888 to 1898, the main forum for his work at this time and one with a strongly Francophile affiliation. These works include his portrait of Philip Wilson Steer, c.1889–90 (National Portrait Gallery, London),21 exhibited alongside a Steer portrait of Sickert himself (whereabouts unknown)22 in the spring 1890 NEAC show; his portrait of the Irish art critic, George Moore, 1890–1 (Tate N03181, fig.2), shown at the NEAC exhibition in winter 1891; his self-portrait, L’Homme à la palette c.1893–4 (fig.3), exhibited at the NEAC in spring 1894; his portrait of Aubrey Beardsley, 1894 (Tate N04655, fig.4), a fellow artist and future art editor of the Yellow Book, exhibited at Van Wisselingh’s Dutch Gallery in 1895; another Self-Portrait c.1896 (Leeds City Art Gallery);23 and his portrait of Fred Winter, the secretary of the NEAC, c.1897–8 (The Phillips Collection, Washington DC). Alongside these, Sickert also published artists’ portraits as illustrations in periodicals, notably of Jacques-Émile Blanche, 1890 (private collection),24 published as part of a series in the Whirlwind in 1890, and of Richard Le Gallienne, 1894 (whereabouts unknown),25 published in the Yellow Book in January 1895.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

George Moore 1890–1

Oil paint on canvas

support: 603 x 502 mm; frame: 792 x 691 x 62 mm

Tate N03181

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1917

© Tate

Fig.2

Walter Richard Sickert

George Moore 1890–1

Tate N03181

© Tate

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

L’Homme à la palette c.1893–4

Oil paint on canvas

760 x 310 mm

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo Brenton McGeachie

Fig.3

Walter Richard Sickert

L’Homme à la palette c.1893–4

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo Brenton McGeachie

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Aubrey Beardsley 1894

Tempera on canvas

support: 762 x 311 mm; frame: 1010 x 553 x 61 mm

Tate N04655

Purchased with assistance from the Art Fund 1932

© Tate

Fig.4

Walter Richard Sickert

Aubrey Beardsley 1894

Tate N04655

© Tate

James Abbott McNeill Whistler 1834–1903

Arrangement in Black, No.3: Sir Henry Irving as Philip II of Spain 1876

Oil paint on canvas

2153 x 1086 mm

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Rogers Fund, 1910

Photo © 2011. The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource / Scala, Florence

Fig.5

James Abbott McNeill Whistler

Arrangement in Black, No.3: Sir Henry Irving as Philip II of Spain 1876

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Rogers Fund, 1910

Photo © 2011. The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource / Scala, Florence

Taken as a whole, Sickert’s portraits of the 1890s adopt the fluid, impressionist language derived from Whistler and engage with the altered gender frameworks provided by Aestheticism. Following Whistler, Sickert eagerly cultivated the personal style and mannerisms of the cosmopolitan dandy in which issues of artifice and performance became key components within the artist’s masculine self-fashioning. His L’Homme à la palette and Aubrey Beardsley demonstrate his allegiance to a Whistlerian repertoire, responding to such works as Whistler’s Arrangement in Black, No.3: Sir Henry Irving as Philip II of Spain 1876 (fig.5), Arrangement in Flesh Colour and Black: Portrait of Théodore Duret 1883–4 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) and Arrangement in Black: Pablo de Sarasate 1884 (Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh). With their debt to the late nineteenth-century revival of interest in Diego Velázquez and Spanish painting,26 the figures are attenuated, the paint thinly applied and the background composed of different patches of black, dark hues and brown.

Sickert’s work was also heavily indebted to that of Edouard Manet, whom he praised as ‘one of the most brilliant and powerful painters who have ever lived’.27 As Moore recorded, ‘the art of Velasquez and Manet was pure instinct’,28 and Whistler, as Sickert wrote in May 1897, ‘is the child of Velasquez’.29 Sickert especially applauded Whistler’s use of spare, dark, often black backgrounds to amplify the presence of the figures. The paintings give few physical details in order to emphasise the ambiguity of the body in a shadowy space, to such an extent that one critic termed them spare, ghostly apparitions and ‘materialised spirits’.30 Sickert put it differently:

This Philip has a simplicity, an intimacy, and a suavity that are all Whistler ... Whistler’s portrait gives exactly what enchanted us, and what we want to remember – the embodied spirit of the rôle.31

To younger artists trained at the Slade who had studied such Spanish sources in the National Gallery in London, Whistler’s and Sickert’s preference for sombre colours in portraiture seemed innovative and inspiring: a modern correlation between the art of the past and a thoroughly contemporary approach to figuration as performance, as ‘rôle’. The validity of this allegiance was further underscored when Whistler’s late Gold and Brown: Self-Portrait c.1896–8 (National Gallery of Art, Washington DC)32 was shown at the inaugural exhibition of the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers in London in May 1898. Whistler had been elected president of the society earlier that year and his reputation was reinforced by the fact that the portrait of his mother, Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1, Portrait of the Artist’s Mother 1871 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris), was the first of his works to be acquired by the French state (for the Musée du Luxembourg). The self-portrait with its red accent signalled the artist wearing the red rosette of the Légion d’Honneur which he had been awarded in 1892.

Following Whistler’s appearance in court in support of Joseph Pennell’s libel suit against Frank Harris and Sickert in April 1897 and his critical remarks about Sickert from the witness box, Sickert’s friendship with the American artist ended abruptly. By July 1907 Sickert would even refuse the term ‘aesthete’, stating that ‘pour moi c’est le plus gros mot que je connaisse’ (For me that is the worst word I know).33 Understating his work’s indebtedness to the American’s in favour of a seemingly more robust and famous French mentor, Edgar Degas,34 Sickert declared emphatically that Degas was ‘the one great French painter, perhaps the greatest that the world has ever known’, confirming that ‘the genius of painting still hovers over Paris’.35

Writing in July 1915, ten years after Whistler’s death, Sickert identified what he saw as the artist’s main weakness, namely his failure to fully adapt his American sensibility, French artistic methods and extravagant exhibition practices to British tastes and requirements. Sickert condemned what he saw in Whistler’s work as an American ‘appreciation for the beauty of old-world accretion in architecture and painting’, and lambasted his theatrical use of ‘Hangings and overpowering frames ... out of all proportion to the matter enclosed in them’, which manifested associations with shop merchandising.36 In his 1915 review of the Whistler show at Colnaghi and Obach’s Galleries, Sickert openly criticised ‘Whistler’s too tasteful, too feminine and too impatient talent [that] had need, for its development, to remain in the severe and informed surroundings of Paris, the robust soil where his art had its birth’.37

One reason for Sickert’s desire to distance himself from the Whistlerian Francophile model was that the promotion of dandified performance, elaborate grooming and masculine posing was, as explained in the opening of this essay, associated by some conservative English critics with a disreputable aestheticism following Wilde’s trial and conviction in 1895. As a result, a charismatic artistic form of masculinity registered to some audiences as an affront to bourgeois English manly norms. To others, it was open to ridicule through its blatant over-identification with the ‘feminised’, and perhaps even its suggestion of a homosexual inclination that demanded urgent repression. In the fashioning of new and convincing correlations of artistic masculinity and modernity within the London art world, what was called for was a style of (self-) fashioning free from any dubious suspicions of copying foreign cosmopolitanism or replicating clichéd bourgeois bohemianism. Equally, in order to register its conviction, any account of all-male camaraderie and close male bonding needed to clearly establish itself as motivated solely by a desire to generate group publicity, attract patrons and supporters, and encourage sales rather than as launching new fashions in artistic dress.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Juvenile Lead (Self-Portrait) 1907

Oil paint on canvas

458 x 510 mm

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.6

Walter Richard Sickert

The Juvenile Lead (Self-Portrait) 1907

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Self-Portrait: The Painter in his Studio 1907

Oil paint on canvas

508 x 610 mm

Art Gallery of Hamilton, Ontario. Gift of the Women’s Committee, 1970

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Art Gallery of Hamilton, Ontario

Fig.7

Walter Richard Sickert

Self-Portrait: The Painter in his Studio 1907

Art Gallery of Hamilton, Ontario. Gift of the Women’s Committee, 1970

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Art Gallery of Hamilton, Ontario

Sickert’s The Juvenile Lead (Self-Portrait) (fig.6), exhibited at the Salon d’Automne in 1907 (under the title L’Homme au chapeau melon; the amended title was added in 1928), and his Self-Portrait: The Painter in his Studio (fig.7), shown at the NEAC summer exhibition in 1907 (under the title The Parlour Mantelpiece), portray the artist in a more serious mood wearing round-lens glasses, in a studio that replicates a domestic interior. In the first, the artist wears an urbane business suit with bowler hat of the type popular with the Edwardian professional and business classes. Described by Sickert as ‘a life-sized head of myself in a cross-light’,38 subsequent reviewers have seen the later addition to the work’s title as reflective of Sickert’s aspirations as a trained amateur actor and as a reference to the older artist’s role as ‘manager’ of the younger ‘juvenile’ members of the Camden Town Group. In the second work, the artist stands, palette and brushes in hand, in front of a canvas with his image reflected in a mirror over a mantelpiece. To add intellectual gravitas, Sickert positions himself flanked by reduced-size casts. On one side, there is a Venus sculpture that the art historian Anna Gruetzner Robins has identified as a variant of the Knidian Venus and, on the other, a copy of Michelangelo’s Dying Slave from the Louvre.39 Within this work, the mirror acts as a practical device that opens up the interior to the viewer, thereby allowing sight of a painting, a canvas with a memo inserted in its frame, and what the art historian Wendy Baron has identified as a stag’s skull or a flayed anatomical figure (écorché) in the background;40 the recognition of these is made more difficult by the darkly shadowed interior and the crusty, textured paintwork.41 Simultaneously, the mirror also stands as a metaphor for self-reflection, invoking ideas of self-creativity, in which Sickert suppresses any overtones of the dandified society portrait painter in favour of more sober professional presentation in a London interior that contains antique and Renaissance sculptures, canvases and artists’ paraphernalia.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Jacques-Emile Blanche c.1910

Oil on paint canvas

support: 610 x 508 mm; frame: 810 x 710 x 62 mm

Tate N04912

Purchased 1938

© Tate

Fig.8

Walter Richard Sickert

Jacques-Emile Blanche c.1910

Tate N04912

© Tate

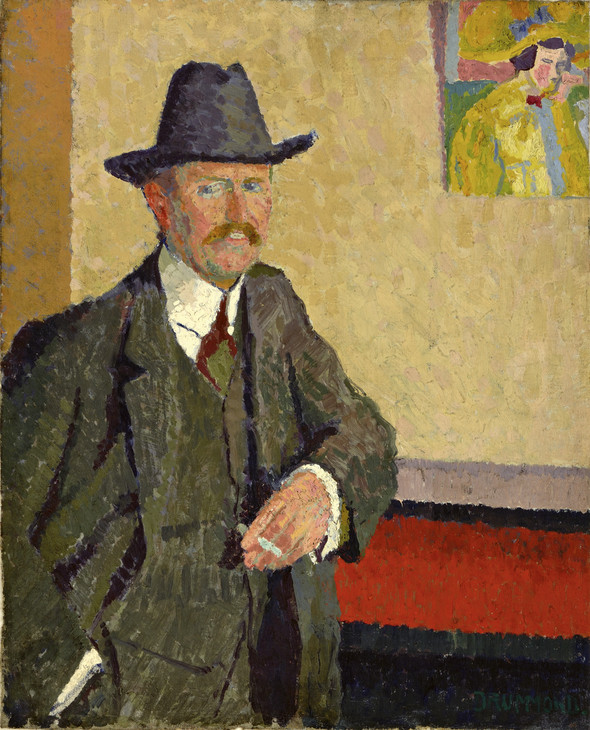

However, given the very different historical factors and institutional conditions that determined the London art world and its audiences, what was urgently called for was the demonstration of a commitment to an English modernity signalled through an incontrovertibly British and manly semiotics of personal public style, however hybrid in its configuration. In the portrait of Blanche the renunciation of earlier dandified costume is registered in Sickert’s deployment of more sombre dress in which the Anglophile Blanche sports a top hat, white cravat and heavy overcoat; he is also depicted as a member of a St. James's private members' club, a localised London that some, if not all, viewers at the NEAC exhibition would recognise as referencing London's distinctive commercial and cosmopolitan modernity.

Relocating to London in 1905, Sickert had made a self-conscious decision to reposition himself within the British art capital, which he had asserted was ‘the most wonderful and complex city in the world’.43 By establishing himself in Fitzrovia and then Camden Town, he, like Gore, who also resided in Mornington Crescent from 1909–12, and Gilman, who sometime lived nearby in Harrington Street, identified himself with the unfashionable north London neighbourhood as opposed to more established creative quarters such as Chelsea, Holland Park or St John’s Wood.

According to fellow member Walter Bayes, it was Sickert who came up with the ‘Camden Town Group’ title, ‘averring that that district had been so watered with his tears that something important must sooner or later spring from its soil’.44 Moreover, this appellation choreographed a collective modernist identity that was emphatically tied to London’s working class geography and was formed within and by the city’s social, artistic and commercial landscapes. Also crucial was the incorporation within the work of distinctive features of working and lower middle class types, dress and interior décor that grounded it in London locations; this registered explicitly with English audiences and more generally as Londonien with French ones.45 As Sickert had argued in a review of an NEAC show in April 1889, what was required for London audiences were indigenous subjects and localised references to offset any sense of a generalised, over-clichéd cosmopolitanism: ‘It is surely unnecessary to go so far afield as Paris to find an explanation of the fact that a Londoner should seek to render on canvas a familiar and striking scene in the midst of the town in which he lives.’46

London, with its impressive art institutions, museums and galleries, art market and art publishing houses, was between c.1905–14 experiencing one of its most dynamic artistic and intellectual periods. British-born artists working in the metropolis had a rich fund of modern subjects and experiences to access. At once the biggest city in Europe and standing at the centre of the largest empire ever known, London was a vast conglomeration of races, cultures and lifestyles in which the conventional markers of social identity lost legibility amongst the growing urban population. As the writer Henry James recorded, it was the capital’s cultural diversity, its dynamism and size that both attracted and shocked newcomers. London is ‘only magnificent ... the biggest aggregation of human life, the most complete compendium of the world’.47 Like many members of the Camden Town Group, artists and writers from all parts of the United Kingdom, continental Europe, North America and all corners of the empire were eager to exploit the city’s formal and informal career opportunities and to embrace its cultural vitality and diversity. As well as Sickert, who lived in France and Italy for long periods, other key members of the Camden Town Group had spent considerable time abroad, sometimes training in foreign academies and art schools. Collective cosmopolitan experiences and continental networks furnished these artists with a broad understanding of alternative styles of artistic masculinity that acknowledged the importance of group sociability and provided new insights into ways of promoting group identity. For some figures, such as Wyndham Lewis, periods away from Britain had clearly expanded native horizons: ‘I became a European’, Lewis declared.48 For others, like Ginner, born in Cannes of Anglo-Scottish descent and educated in Paris, and Sickert, born in Munich into an artistic family of Danish and Anglo-Irish descent, such international backgrounds and experience produced, as William Rothenstein recalled of Sickert, a polyglot cosmopolitan: ‘a finished man of the world. He was a famous wit; he spoke perfect French and German, very good Italian and was deeply read in the literature of each. He knew his classical authors.’49

Returning to the British capital from abroad, artists experienced London as a dynamic metropolis in a position of commercial and cultural authority at the heart of the British Empire. The city supported thriving artistic coteries that were home to many foreigners; one of the key factors in London’s success was the fact of immigration.50 Alongside Americans, Canadians, Indians, Australians and New Zealanders, there were French, German, Russian and Polish immigrant groups who were all self-exiled into a bustling metropolis. Like Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, John Singer Sargent and Jacob Epstein, many of the Anglo-American literary and artistic compatriots had crossed the Atlantic as part of a larger wave in search of trans-Atlantic bohemianism. London’s Yiddish-speaking, Chinese and Afro-Caribbean communities had also expanded considerably in a culture that had economic opportunities as well as widespread freedoms of expression. Liberated from the provincial cultures within which many had been born, for émigrés the British capital was both a powerfully alluring and yet simultaneously alien place. It was this diversity that registered most forcefully and was believed by many to be the reason why London was the embodiment of the modern metropolis and the finest capital city of the English-speaking world.

The influx of British expatriates and other émigrés into London further demonstrated the increasingly rapid transfer between British and other art cultures as well as the escalating pace of change evident in the contemporary art market. One consequence of this mobility in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was that operational models from abroad were deployed to revitalise both existing and new artists’ societies and debating groups. Edwardian London offered rich pickings within a liberating milieu alert to the pleasures of its expanding consumer markets and its own self-conscious significance. It provided the opportunities and locales within which modern London-based artists could map out new, vital and creative urban geographies and professional networks. Cafés, tea rooms, libraries, bookshops and editorial offices supported and accommodated numerous artistic and literary events with all members participating in the informal social scene and nightlife. Exhibitions, poetry clubs, fashionable soirées, musical recitals and artists’ studios as well as music halls, variety theatres, restaurants and cinemas were popular venues and underlined the sense of energetic modernist experimentation out of which new social and sexual mappings of the metropolis could be forged.

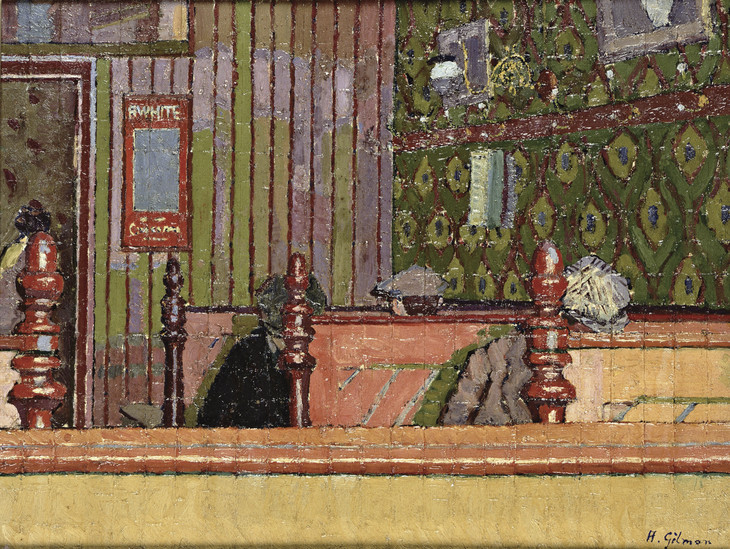

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

The Café Royal 1911

Oil paint on canvas

support: 635 x 483 mm; frame: 878 x 725 x 100 mm

Tate N05050

Presented by Edward Le Bas 1939

© Tate

Fig.9

Charles Ginner

The Café Royal 1911

Tate N05050

© Tate

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

An Eating House c.1913–14

Oil paint on canvas

572 x 749 mm

Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust

Photo © Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.10

Harold Gilman

An Eating House c.1913–14

Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust

Photo © Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

The Café Royal was just such a location popular with London’s artistic and literary coteries and was captured by Charles Ginner in 1911 (Tate N05050, fig.9). An audience’s recognition of the location in Ginner’s painting would have grounded the venue as distinctively urban and specifically set in London. The view is from a seat in the Brasserie or Domino Room, which had retained its original interior decoration from the 1860s with red plush seats and tall mirrors. The work also exploits references to Vincent van Gogh’s Interior of the Restaurant Carrel in Arles 1888 (private collection),51 shown first at the International Society exhibition in London in 1908 and later at the Post-Impressionist and Futurist show organised by Frank Rutter in London in 1913. Ginner and Gilman had seen van Gogh’s work in the Bernheim collection in Paris in early autumn 1910, which Ginner later described as ‘a sight unsurpassed in beauty and intensity’.52 They saw more works at Roger Fry’s Manet and the Post-Impressionists exhibition at the Grafton Galleries in London from November 1910–January 1911. This was the first time that a large selection of paintings by van Gogh had been on display in London and they attracted considerable press attention, especially his Self-Portrait in Front of an Easel 1888 (van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam).53 Anna Gruetzner Robins claims that Drummond’s Portrait of Charles Ginner (fig.1), like Gilman’s An Eating House c.1913–14 (fig.10),54 was similarly indebted to van Gogh.55 However, to mitigate such cosmopolitan linkages, in Gilman’s An Eating House the flat caps worn by the male diners, the details of interior layout and seating, the cheap decoration of the café, as well as the presence of the English language sign or chalk board, would have registered its credentials as a working class location in a British urban setting, quite possibly Camden Town (as claimed by Ginner).56

Orchestrating the Camden Town Group identity in the promotional spaces of the British press

In order to establish how and in what ways the Camden Town Group negotiated these shifting boundaries to promote themselves as ‘serious’ avant-garde artists directly engaged with London’s cosmopolitan modernity, I want to investigate how the artists orchestrated press interest in their work and also what kinds of new readers were appearing in this period. Within the early decades of the twentieth century, new conditions emerged that informed artists’ social and commercial behaviour towards the press and shaped professional opportunities for their presentation in England.57 These demanded that artists, like all intellectuals operating within the expanding public sphere, engage with the developing opportunity for self-advertisement. As the writer Ford Madox Ford urged readers of the English Review in 1909, what was wanted was not a flaccid imitation of someone else’s life-experience, but a forceful rendition of one’s own: ‘We live in our day, we live in our time, and he is not a proper man who will not look in the face his day and his time.’58

Expanding print technologies generated a popular and specialist art press that sought to engage new publics for art and to present professional opportunities for men and women to elucidate their distinctive outlooks as journalists, writers and critics. By 1910, as a result of widespread literacy and the growth of ‘New Journalism’,59 London supported nineteen morning and ten evening newspapers, and dozens of weekly, monthly and quarterly journals that attested to the intellectual and commercial dynamism of the metropolis. As cultural critic Raymond Williams has argued, this unprecedented proliferation of publications reinforced London’s claim to modernity, since ‘there is a persistent intellectual hegemony of the metropolis, in its command of the most serious publishing houses, newspapers and magazines, and intellectual institutions, formal and especially informal’.60 As advertising revenues surpassed subscription returns, the rise of mass market periodicals allowed the latest tastes, artistic developments and literary debates to be identified and reported in considerable complexity. Moreover, the reach of the British art press was substantially expanded internationally as art reviews were translated for publication on the continent (often by dealers themselves) or syndicated across the Atlantic and throughout the British Empire to other parts of the English-speaking world.

Consequently, the period c.1905–14 saw important transformations in the relationship of artists with the art market, patronage, publishing and the mass media. Increasingly, artists wrote their own statements, polemical manifestos and catalogue introductions to frame their intentions. These changes bred a more sophisticated awareness of the ways in which commercially orientated journalism generated newsworthy stories for its readers and advertising revenues for its owners. To exploit the growing interest in the London-based avant-garde and to position its work and concerns as novel and newsworthy, the press circulated art news, celebrity gossip and artist personality profiles, a development that had occurred in the late nineteenth century but expanded considerably in the twentieth century. Furthermore, such increased exposure allowed racy accounts to be circulated in serialised biographies and behind-the-scenes exposés of life in artists’ studios and in art circles. For example, the popular monthly, the Strand, had ‘Portraits of Celebrities’, ‘Artists at Home’ and ‘Illustrated Interviews’ features, or, more generally, ‘In the Studio’ profiles. Even the Studio had its own, less formal, ‘Studio Talk’ columns to appeal to such insider interests.

One of the newly emerging spaces available for energetic self-promotion was the many small circulation magazines that were launched and published in the period c.1905–14. These included the recently established New Age (bought by Alfred Orage in 1907) and English Review (founded by Ford Madox Ford in 1908). In addition to these literary reviews, new art journals such as the Burlington Magazine (edited by Roger Fry from 1903) and the Art News (founded by Frank Rutter in 1909), as well as older periodicals such as the Studio (founded in April 1893), offered more specialist coverage of international modern art. As a result of the growing interest in contemporary art and in art news, art journalism became more prominent in many weekly, monthly and quarterly periodicals, magazines and newspapers, and artists found such an energetic promotional culture hard to ignore, even if they did not approve of its mass market practices.61

From late 1908 Sickert exploited these journalistic openings in his active and impassioned role as an art critic. His most prolific period as an art writer was from 1910 when he was appointed critic for the New Age and the Art News, which from its launch in October 1909 claimed to be ‘the only Art Newspaper in the United Kingdom’ and was the chief organ of the newly formed Allied Artists’ Association.62 Sickert also published regularly in the English Review from January 1912 and in the Burlington Magazine from July 1915. Following Whistler’s provocative model for generating self-publicity, Sickert’s writing was clearly self-promoting and often controversial, occasionally attracting outrage that produced litigation (as Joseph Pennell’s 1897 libel case against Sickert underscored). He also published portrait pen and ink drawings in the New Age from June–August 1911 and selected a ‘modern drawings series’ from January–March 1914. To capitalise on this increased exposure, Sickert exhibited a great deal in London from 1911 to 1914 and he showed at the Venice Biennale in summer 1912 and the Armory Show in New York in February 1913. Collectively, Sickert’s industry in these years resulted in greater national and international exposure for his art as well as the publication of hundreds of reviews, articles, catalogue prefaces, lecture transcripts and letters to the press. Furthermore, as Mark S. Morrison has demonstrated in his 2001 study, these ‘mass market journals and the impact that they had on the intellectual press helped set the stage for modernism’s understanding of the public sphere in the twentieth century’, adding a sense of intellectual prestige and cultural authority to newsworthy developments.63

Sickert’s involvement with the English Review and the New Age placed him at a particular nexus in terms of contemporary art, literature and politics. The English Review published articles mainly by Liberals, Radicals and Socialists and, as Morrison has argued, ‘did not, as an editorial policy, follow a doctrinaire or partisan line in its interests or editorials’.64 This outlook was demonstrated by incorporating articles and reviews on a wide range of popular culture, including music hall portraits and a series on ‘the music hall as a factor in popular life’ analysed in relation to the ‘circumstances and ideals of the lower middle class’.65 Austin Harrison, who replaced Ford Madox Ford as editor in 1910, assured the journal’s readers that its objective was ‘to gather within its covers the most intimate writings of the best authors of the day, both in England and on the continent’. 66 Harrison also continued Ford’s practice of publishing stories on popular culture, especially the music hall and burlesque, in order, as Morrison notes, ‘to appeal to the widest strata of readers – from the lower middle class music hall audiences to the upper class society set’.67

In a similar vein, under Orage’s editorship, the New Age addressed contemporary developments in art and literature of interest to a broadly socialist and liberal readership,68 successfully engaging a newly literate working and lower middle class readership. As the literary critic Robert Scholes has argued, the readership of the New Age was socially diverse: ‘most of the men and women who made it what it was, if they had been to college or university, had studied at the University of London, at the provincial universities or, like Orage himself, at teacher training colleges’.69 In a 2007 article Ann L. Ardis goes further, suggesting that the journal’s ‘rank and file readers were the socialist autodidacts and the left leaning graduates of the working men’s colleges, teacher’s colleges and extension lecturing circuits that Orage set out to uplift socially when he and Holbrook Jackson first founded the Fabian Arts Group in 1906’.70

It is against the widening social background of readers and sense of a socially committed, specifically London-based engagement with a cosmopolitan modernity that the Fitzroy Street and Camden Town groups’ interests and Sickert’s writing establishes a sort of inclusive fellowship. As Sickert instructed his fellow Fitzroy Street member, Nan Hudson:

I want, (and this we can all understand and never say) to get together a milieu rich or poor, refined or even to some extent vulgar, which is interested in painting and in the things of the intelligence, and which has not ... an aggressively anti-moral attitude.71

Such intellectually hungry and socially broad metropolitan audiences would have recognised and understood some, if not all, of the references in Camden Town Group art and writing to contemporary literature and theatre, to London’s social and sexual manners, and to the city’s working class geographies and popular culture. The reviews and debates published in the art journals provided readers with up-to-the-minute and catholic accounts of contemporary art developments in Britain and abroad without promoting orthodox attitudes.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Minnie Cunningham at the Old Bedford 1892

Oil paint on canvas

support: 765 x 638 mm; frame: 915 x 787 x 69 mm

Tate T02039

Purchased 1976

© Tate

Fig.11

Walter Richard Sickert

Minnie Cunningham at the Old Bedford 1892

Tate T02039

© Tate

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Noctes Ambrosianae 1906

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 762 mm

Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

Fig.12

Walter Richard Sickert

Noctes Ambrosianae 1906

Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

In this respect, Sickert’s return to London music hall subjects in 1906, which he had first explored in the 1880s and 1890s in such works as Minnie Cunningham 1892 (Tate T02039, fig.11), made his mark in public. At the following spring’s NEAC show Sickert exhibited a music hall interior, Noctes Ambrosianae 1906 (fig.12), to such dramatic effect that the critic George Moore wrote tersely: ‘Sickert has come back.’72 The work depicts working class spectators sitting in the cheapest gallery seats – the ‘gods’, as they were colloquially called – of the Middlesex Music Hall in Drury Lane, Covent Garden. The title operated on a number of levels to offer viewers access to more or less sophisticated levels of association.

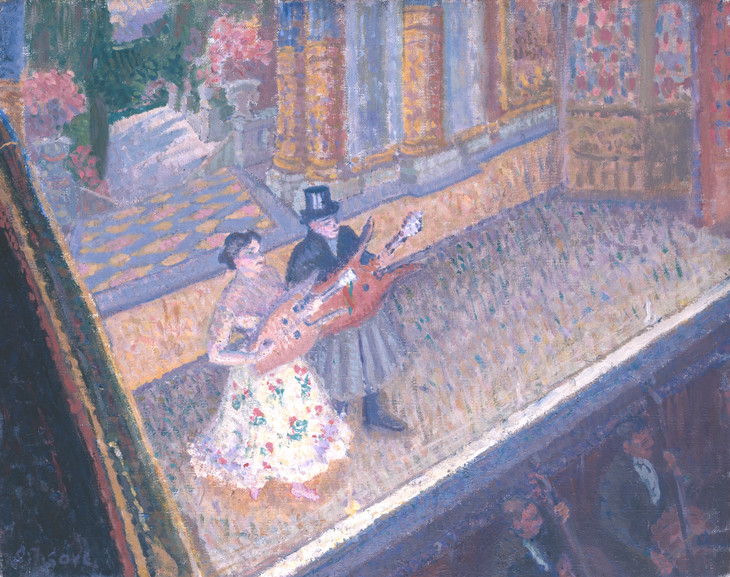

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Gauguins and Connoisseurs 1911

Oil paint on canvas

838 x 717 mm

© Private collection

Fig.13

Spencer Gore

Gauguins and Connoisseurs 1911

© Private collection

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Inez and Taki 1910

Oil paint on canvas

support: 406 x 508 mm; frame: 608 x 710 x 52 mm

Tate N05859

Purchased 1948

Fig.14

Spencer Gore

Inez and Taki 1910

Tate N05859

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Rule Britannia 1910

Oil paint on canvas

unconfirmed: 762 x 635 mm; frame: 970 x 845 x 115 mm

Tate T06521

Presented by the Patrons of British Art through the Tate Gallery Foundation 1992

Fig.15

Spencer Gore

Rule Britannia 1910

Tate T06521

Exploiting this cultural eclecticism, Sickert’s articles are peppered with casual references that incorporate not only specialist artistic and classical terms alongside phrases in French, German and Italian as well as Venetian dialect, but also bits of Cockney slang and well-known music hall refrains. The liberal smattering of such a wide range of erudite and popular sources, often translated or noted alongside the original to make unfamiliar readers understand the reference, registered not only a more democratic impulse, but a left-leaning, unorthodox one that gestured to the far from homogenous nature of socialism existing in Britain at this time. By publishing the latest ideas from abroad alongside London-based authors’ essays, these journals fostered a cosmopolitan intellectual exchange that registered with a socially wide English readership without loosening its localised focus and distinctive political edge.74

I should like now to consider the significance that working or lower middle class referencing, sometimes specifically to the Camden Town neighbourhood, had in Camden Town Group works that present portraits of artists in domestic spaces or which depict interiors with figures, often women, and sometimes female nudes.

Artistic self-fashioning in Camden Town’s ‘real’ and ‘imaginary’ geographies

The Camden Town Group’s appropriation of urban working class typologies and environments and the use of recognisable London locations became a conspicuous strategy in the group’s desire to stake a collective stance within the English avant-garde.75 Nevertheless, as Sickert recognised in an article in the New Age in May 1910, the inclusion of rougher working class models in artworks was not in itself a guarantee of any successful claim to working class credentials. He declared:

All figures enact their scenes in a somewhere. I am inclined to think that, in good composition, the order of consideration must be from the somewhere to the figures in it. The opposite order of design ... is generally fraught with disaster.76

Consequently, attention to the revealing details of interior architectural space, layout and decoration alongside accurate depiction of costume, cosmetics, deportment and gesture was not, by itself, sufficient for a convincing rendition of the territories of the London poor. By remembering at all times, as Sickert stressed, the importance of that imaginative ‘somewhere’ over who was being depicted, the collapse of artistry into the reportage style of the ethnographic investigator, or the danger of invoking the moralised and religious sentiments of urban social reformers, could be avoided.

By 1900 intimate paintings of aesthetic interiors, women in interiors, or artists’ portraits in domestic spaces had become a familiar feature at NEAC exhibitions. Moreover, such types of painting were increasingly identified by English audiences with the importation of formal and technical languages derived from French impressionist and post-impressionist painting.77 When in June 1911 the Camden Town Group organised its first show, thirteen of its members had withdrawn from the NEAC and the three remaining contributors – Drummond, Ginner and John Doman Turner – had never exhibited with the club. Eschewing the aesthetic interiors with their ‘plain walls, highly polished furniture, a green door or dado, one figure or more and frequently a green-shaded lamp’ that one critic noted ‘reappear exhibition after exhibition’ at the NEAC,78 Sickert, Gore and Gilman turned, instead, to representing urban working class surroundings. Their works picture dingy interiors, which were carefully assembled using second-hand furniture in their Mornington Crescent and Camden Town studios, with appropriately dressed and seemingly roughly mannered models posed in provocative, sometimes sexually charged scenarios, producing what a later writer called ‘sordid scenes in a sprightly manner’.79

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

North London Girl c.1911–12

Oil paint on canvas

support: 762 x 610 mm; frame: 814 x 712 x 102 mm

Tate T00027

Bequeathed by J.W. Freshfield 1955

Fig.16

Spencer Gore

North London Girl c.1911–12

Tate T00027

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

L'Américaine 1908

Oil paint on canvas

support: 508 x 406 mm; frame: 748 x 649 x 55 mm

Tate N05090

Bequeathed by Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck 1940

© Tate

Fig.17

Walter Richard Sickert

L'Américaine 1908

Tate N05090

© Tate

Sickert’s mantra, as declared in the Art News in May 1912, was that ‘the more our art is serious, the more will it tend to avoid the drawing-room and stick to the kitchen. The plastic arts are gross arts, dealing joyously with gross material facts.’80 One way to achieve this specificity was through attention to nuances of dress and fashion that fixed appearance to time and place. For example, Gore’s North London Girl c.1911–12 (Tate T00027, fig.16), like Sickert’s L’Américaine 1908 (Tate N05090, fig.17) and The New Home 1908 (Ivor Braka Ltd),81 features a working class model in a domestic interior given a sense of contemporaneity by reference to fashionable dress and cosmetics. As Gore told Doman Turner, ‘it’s not the business of the painter to dress his sitter to show his taste in dress, but to have them in the clothes naturally characteristic of them’.82 The drawing by Sickert entitled The Straw Hat c.1911 (Tate N05309, fig.18) demonstrates the artist’s concern to catch meaningful and significant details of costume as well as that of comportment. Likewise, Sickert often selected working class models because of their background and manner. In preparation for L’Américaine, Sickert had ‘two divine coster girls’ model for him,83 who wore ‘hats called “American sailors”’,84 and ‘dressed in the sumptuous poverty of their class’,85 a remark that identifies not only his admiration for them, but something of an ethnographic fascination with appearance and class.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Straw Hat c.1911

Graphite on paper

support: 279 x 190 mm

Tate N05309

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1941

Fig.18

Walter Richard Sickert

The Straw Hat c.1911

Tate N05309

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Mornington Crescent Nude 1907

Oil paint on canvas

475 x 508 mm

Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

Fig.19

Walter Richard Sickert

Mornington Crescent Nude 1907

Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

Another way for the Camden Town Group artists to ground their work for English audiences was by signalling real or imagined geographical locations in their works’ titles and by incorporating convincing interior décor and details into the interior settings. Around 1907 Sickert produced a series of pictures, such as Mornington Crescent Nude: Contre-Jour 1907 (Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide),86 and three works entitled Mornington Crescent Nude 1907 (fig.19, private collection and University of Hull Art Collection).87 Alongside Gore’s Behind the Blind 1906 (whereabouts unknown) and Interior with Nude Washing 1907 (fig.20), these seem to have been painted in Sickert’s first-floor studio at 6 Mornington Crescent (or, if not, in the Fitzroy Street studio). The works openly demonstrate Sickert’s and Gore’s commanding assurance of the ways in which the nude was being modernised and updated by continental artists. A noticeable feature of Sickert’s display of similar London paintings at the 1905 Salon d’Automne was that they were given French titles, being destined for the Parisian art market.88

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Interior with Nude Washing 1907

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 457 mm

Leeds Museums and Galleries (Leeds Art Gallery)

Photo © Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery) UK/The Bridgeman ArtLibrary

Fig.20

Spencer Gore

Interior with Nude Washing 1907

Leeds Museums and Galleries (Leeds Art Gallery)

Photo © Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery) UK/The Bridgeman ArtLibrary

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Nude at a Window c.1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 610 x 508 mm

Tate T13227

Accepted by HM Government in lieu of inheritance tax and allocated to the Tate Gallery 2010

Fig.21

Harold Gilman

Nude at a Window c.1912

Tate T13227

The use of figures in an interior against a background of brightly patterned wallpaper or interior furnishings was a characteristic of the work of the French artists Edouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard. These two painters were frequent contributors to the International Society exhibitions in London. They had regular contact with British dealers and collectors, and both were considered ‘the accepted masters of Intimist painting’.89 Considering Sickert’s Mornington Crescent and Camden Town nudes along with Gore’s Girl Seated on a Bed 1910 (private collection)90 and Gilman’s A Nude in an Interior 1911 (Yale Center for British Art) and Nude at a Window c.1912 (Tate T13227, fig.21), the critic Frank Rutter proposed that although their works have a broader colour range than Vuillard and Bonnard, the Camden Town Group artists ‘might with least confusion be regarded as the “intimists” of England’.91 When the French critic Paul Jamot saw Sickert’s London interiors at the 1906 Salon d’Automne, he recognised that ‘Sickert is wavering between Bonnard and Whistler’.92

Revealingly, where the French artists’ work addresses the domestic sites of bourgeois life and catches the tasteful interior decoration in a heightened, decorative palette, Sickert’s, Gore’s and Gilman’s paintings knowingly rework these domestic scenarios in relation to London working class spatial architecture and its recognisable interior layouts. If, as Sickert declared in September 1910, Camden Town was his ‘Barbizon’,93 then his references to Mornington Crescent fix the location succinctly. Sickert and Gore were knowingly exploiting the neighbourhood’s working class connotations and to such effect that Sickert was charged by one critic with producing ‘Slum Art’.94 By 1914 a reviewer in the Illustrated London News complained that these spaces and accoutrements had become clichéd and commonplace in Camden Town Group work: ‘Of [Sickert’s] disciples there are a multitude and mostly paint the same back bedroom. The washstand, the iron bedstead and the unsafe chair appears in all of their canvases.’95

It is significant that many of Sickert’s works from c.1904–7 feature a naked woman standing in front of a wardrobe mirror in a bedroom. He employed the device of a wardrobe mirror to complicate the relationship between self and space and, to some extent, to sexualise the understanding of the studio as a setting for the production of art. This strategy reiterates the form of his early music hall paintings, with their teasing reflections, repetitions and echoes, articulating what George Moore called ‘the enigma of the artificial life of the stage’.96 It also produces a sense of visual dislocation that disrupts any easy narrative interpretation and, in the manner of Degas, achieves curious ‘through the key hole’ viewpoints that unnerved many viewers. It even led some critics to characterise his vision as alienated and markedly non-empathetic. After seeing the Stafford Gallery exhibition in June 1911, Roger Fry condemned what he described as Sickert’s ‘curiously detached’ vision and the almost obsessive recording of surfaces and appearances. Consequently, as Fry complained, the painter’s ‘persistent devotion to the banal and trivial situations of ordinary life’ and to the ‘squalid’ grated not only with bourgeois propriety, but with Fry’s own artistic tastes, for varied and differing reasons.97 ‘Things for him,’ wrote Fry, ‘have only their visual values, they are not symbols, they contain no key to unlocking the secrets of the heart and spirit.’98

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Off to the Pub 1911

Oil paint on canvas

support: 508 x 406 mm; frame: 695 x 595 x 45 mm

Tate N05430

Presented by Howard Bliss 1943

© Tate

Fig.22

Walter Richard Sickert

Off to the Pub 1911

Tate N05430

© Tate

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Ennui c.1914

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1524 x 1124 mm; frame: 1741 x 1340 x 110 mm

Tate N03846

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1924

© Tate

Fig.23

Walter Richard Sickert

Ennui c.1914

Tate N03846

© Tate

In another series of works, including Off to the Pub 1911 (Tate N05430, fig.22), A Few Words: Off to the Pub c.1912 (Nicholas Snowman),99 Ticking Him Off c.1913 (private collection)100 and Ennui c.1914 (Tate N03846, fig.23), Sickert encapsulated what he called ‘the intensity of dramatic truth in the modern conversation-piece or genre picture’.101 The works depict a male and female figure (sometimes two women) in a domestic setting, usually a modest working class room, in which the title sets off possible narrative interpretations suggestive of familial tension, marital disharmony or psychological anxiety. Wendy Baron sees these works as marking a shift in focus in which ‘melodrama ... gives way to anecdotes of everyday domesticity’,102 since they invoke, although do not explicitly illustrate, aspects of working class relationships within enclosed, relatively poor, urban domestic spaces. The man’s flat cap and dress in several of these works indicate conspicuous class identities while the furnishings of the room, often with cheap wallpaper and unpretentious fireplaces, are evocative of working class decoration (often featuring recognisable studio props that reappear in a number of works).

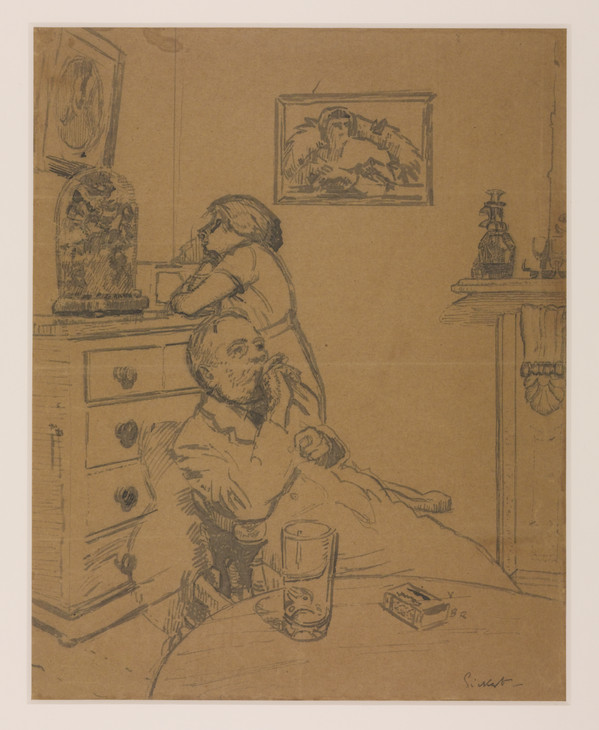

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Study for 'Ennui' 1913–14

Ink on paper

support: 419 x 340 mm; frame: 605 x 505 x 20 mm

Tate T00350

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1960

© Tate

Fig.24

Walter Richard Sickert

Study for 'Ennui' 1913–14

Tate T00350

© Tate

The critics’ conviction that Sickert’s works were illustrations of known places or actual events was further tested by The Camden Town Murder c.1907–8 (fig.25) and L’Affaire de Camden Town 1909 (fig.26). Both works made reference to the vicious sex murder of Emily Dimmock on 12 September 1907 and exploited the press publicity and public fears regarding the event, even though it appears that Sickert was in Dieppe at the time. While composing these, as his friend Marjorie Lilly recalled, Sickert would carefully ‘assume the part of the ruffian’ sporting a ‘red Bill Sykes handkerchief’ tied in a knot around his neck which ‘played a necessary part in the performance of the drawings’.106 Lisa Tickner has demonstrated that Sickert must have known sources from tabloid crime stories in the popular and police press and mobilised the widespread fascination with the savage and macabre Camden Town murder to attract publicity. Tickner maintains that the works ‘do not use the available “language” of illustration for sensational events, evident in the depictions of the Camden Town Murder in such publications as the Illustrated Police Budget and News’, yet she reasons correctly that ‘Exhibiting murder paintings at the Camden Town Group’s début exhibition in 1911 had a manifesto implication’.107

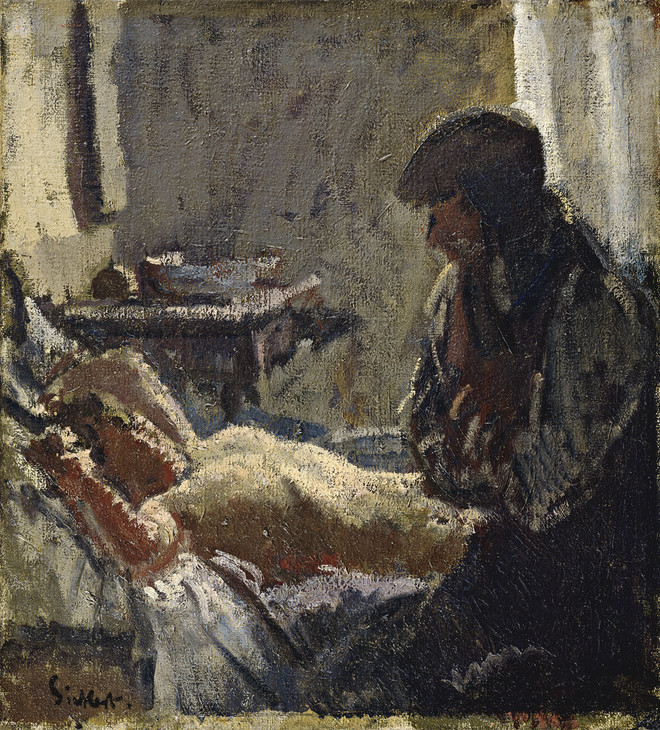

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Camden Town Murder c.1907–8

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 406 mm

Daniel Katz Family Trust

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Daniel Katz Family Trust

Fig.25

Walter Richard Sickert

The Camden Town Murder c.1907–8

Daniel Katz Family Trust

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Daniel Katz Family Trust

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

L'Affaire de Camden Town 1909

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 406 mm

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Photographic Survey, Courtauld Institute of Art

Fig.26

Walter Richard Sickert

L'Affaire de Camden Town 1909

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Photographic Survey, Courtauld Institute of Art

It is clear that Sickert’s titles should not be interpreted too literally as accurate indications of social reality but instead as general allusions carrying broad resonances. As the art historian Simon Watney has argued:

like so much of Sickert’s work ... the title tempts one to draw conclusions , greatly in excess of what is actually in front of one’s eyes ... They usually anchor his pictures to a particular field of cultural associations in an essentially open-ended manner, carrying with them suggestions of possible narrative contexts.108

In a similar vein, Tickner stresses that Sickert was cavalier about titles: ‘Titles do more than designate works ... They frame them. They cue the audience in particular ways.’109 Tickner proposes that whereas Whistler used titles to avoid narrative connotations, Sickert achieves the opposite: the titles actively invite narrative speculation and innuendo, like captions in satirical magazines, headlines in popular newspapers and refrains in music hall songs.110 This strategy is deployed in metal-bedstead nudes such as La Hollandaise c.1906 (Tate T03548, fig.27) that force the physicality of the working woman’s body onto the picture plane, thereby achieving a highly dramatic and provocative interrogational effect. They also highlight, through the presence of the rough iron bedstead in a badly illuminated, seedy bedroom, Sickert’s relocation to London (a move confirmed explicitly in some of their titles by using ‘Fitzroy Street’, ‘Camden Town’ and ‘Mornington Crescent’ affixes). These titles are both specific enough to designate a London neighbourhood and general enough to signal broad reference points to urban working class culture. The French critic Louis Vauxcelles got the message broadly right when he declared: ‘Here is a series of nudes, painted at twilight, amongst the impoverished disorder of cluttered hotel rooms ... a nocturnal poem of London destitution and prostitution.’111

For informed Londoners these interior scenes, fraught with psychological and sexual tension, offered valuable imaginative openings onto artists’ lives, homosociality and the racy goings on, real or imagined, in north London studios. In their meticulously orchestrated dramas of naked female models posed on iron bedsteads, carefully positioned props and suitably arranged dingy interiors, these works referenced for metropolitan art audiences a whole range of shifting meanings and associations that inflected wider class instabilities and gender anxieties across the period c.1905–14. Moreover, they revealed more about the modern English artist’s urgent desire to fashion new and more virile avant-garde identities out of and rooted within London’s modernity than they did about the actualities of working class life and conditions in Camden Town and Mornington Crescent.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Self-Portrait: The Bust of Tom Sayers 1913

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 503 mm

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Fig.28

Walter Richard Sickert

Self-Portrait: The Bust of Tom Sayers 1913

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

As Ludmilla Jordanova has argued in a 2005 chapter on the subject, portraits and self-portraits

participate in conversations about art and artists, about their roles in the wider world. Certainly they can be intimate, introspective, confessional, but they are also calling cards, statements about patronage, ambition, traditions, national identity, gender and age.112

The Camden Town Group’s self-portraits, portraits of artist-colleagues and the depiction of artists’ studios, art galleries and their London socialising venues that I have considered signal how the available repertoires for such public self-fashioning were being updated and revised c.1905–14. As I have argued, these modernising forms offered new ways of approaching group formations as well as narrating artists’ lives, lifestyles and their place in the modern experience of the city.113 In particular, Sickert’s specific London (self-) identification alongside the sense that he was in touch with popular culture and working class life reiterated an eclectic yet distinctive approach; it was one that was central to the Camden Town Group’s self-positioning and underpinned its claims for visibility and authority within the pre-Great War English artistic avant-garde.

Notes

For the historical periodisation, membership and development of the Camden Town Group, see Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, Scolar Press, London 1979 and Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Ashgate, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, and Robert Upstone (ed.), Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2008. For the emergence of a cosmopolitan modernism in London, see Peter Brooker, Bohemia in London: The Social Scene of Early Modernism, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2007, p.9.

The membership of the Allied Artists’ Association included Walter Bayes, Robert Bevan, Harold Gilman, Charles Ginner, Spencer Gore, J.D. Innes and Walter Sickert from 1908, Malcolm Drummond from 1910, and J.B. Manson, William Ratcliffe and John Doman Turner from 1911.

Walter Sickert, ‘The New English and After’, New Age, 2 June 1910, p.109, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2000, p.241. The New Age has been digitised as part of The Modernist Journals Project, http://dl.lib.brown.edu/mjp/ .

Quote from a review of ‘Recent Work by Frank Brangwyn’, Studio, vol.52, no.215, February 1911, p.4. In the review, Brangwyn is praised for remaining ‘independent’ from such trends which it claims are detrimental to ‘great art’ and to establishing a healthy relationship between the artist and the public.

Walter Sickert, ‘Little Pictures for Little Patrons’, New Age, 11 August 1910, in Robins (ed.) 2000, p.271.

For the impact of the Oscar Wilde trials upon artistic self-fashioning, see my ‘Precarious Poses: The Problem of Artistic Visibility and its Homosocial Performances in Late-Nineteenth-Century London’, Visual Culture in Britain, vol.8, no.1, 2007, pp.73–103.

Walter Sickert, letter to Nina Hamnett, not dated, private collection; quoted in Matthew Sturgis, ‘Sickert and Recreational Refreshment in Camden Town’, in Tate Britain 2008, p.38.

Walter Sickert, letter to Ethel Sands and Nan Hudson, June 1911, Tate Archive TGA 9125/5, no.77; quoted in Robert Upstone, ‘Painters of Modern Life: The Camden Town Group’, in Tate Britain 2008, p.21.

Lisa Tickner, ‘Men’s Work? Masculinity and Modernism’, in Norman Bryson, Michael Ann Holly and Keith Moxey (eds.), Visual Culture: Images and Interpretations, Wesleyan University Press, Hanover and London 1994, pp.42–82. In the context of these arguments, the Camden Town Group’s conscious refusal of women members appears anomalous, even outdated and sexist, since sexual emancipation was a feature of London’s social world. The group’s personal circles and professional networks involved energetic and knowledgeable women artists, writers and intellectuals who were conspicuous participants in London’s vibrant cultural scene. The vigour of Anna Hope (Nan) Hudson and Ethel Sands, close friends of Sickert’s from 1907, in hosting parties, events and dinners was testament to transformations in contemporary social-sexual relationships. As Peter Brooker has stressed, this confident social worldliness resulted in women coming much more to the fore as independent figures in political and cultural life. These ‘bohemian-women’ also comprised members of the first generation of women artists to attend the Slade School of Art, including Nina Hamnett, Helen Saunders, Jessica Dismorr, Iris Tree and Dora Carrington. Moreover, in a same-sex relationship, Hudson and Sands were part of a lively and stimulating lesbian intellectual community in London that publicised freer sexual attitudes and included a significant number of other women artists, writers and actresses. See Brooker 2007, pp.8–9.

See Brandon Taylor, ‘Foreigners and Fascists: Patterns of Hostility to Modern Art in Britain Before and After the First World War’, in David Peters Corbett, Ysanne Holt and Fiona Russell (eds.), The Geographies of Englishness: Landscape and the National Past 1880–1940, Yale University Press, London and New Haven 2002, pp.172–3.

Walter Sickert, letter to Mrs Humphrey; quoted in Wendy Baron and Richard Shone (eds.), Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992, p.40.

According to Wendy Baron these included Signor de Rossi 1901 (Hastings Museum and Art Gallery), Mrs William Hulton 1901 (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford), Self-Portrait with La Giuseppina 1903–4 (private collection) and Self-Portrait c.1903–4 (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) amongst many studies for portraits and figure studies. See Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, Yale University Press, London and New Haven 2006, pp.276–301.

Other works that I could have examined include J.B. Manson’s Self-Portrait c.1912 (Tate N04929) and Self Portrait: The Fitzroy Street Studio c.1911 (The Fine Art Society), Sickert’s Harold Gilman c.1912 (Tate T00164), Bevan’s Self-Portrait c.1914 (National Portrait Gallery, London) and Gore’s Self-Portrait 1914 (National Portrait Gallery, London).

See Lisa Tickner, Modern Life and Modern Subjects: British Art in the Early Twentieth Century, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 2000, pp.199–200.

Reproduced in Baron 2006, no.56, and at National Portrait Gallery, http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw06010/Philip-Wilson-Steer?LinkID=mp04275&role=sit&rNo=0 , accessed September 2010.

See Gary Tinterow and Geneviève Lacambre (eds.), Manet/Velázquez: The French Taste for Spanish Painting, exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2003, pp.539–42. A major monograph on Velázquez was published by the art critic R.A.M. Stevenson in 1895, The Art of Velasquez, George Bell & Sons, London, that claimed him for impressionism and generated significant interest in the Spanish artist’s work in Britain.

George Moore, Impressions and Opinions, David Nutt, London 1891, pp.334–8; quoted by Kenneth McConkey, ‘The Theology of Painting – The Cult of Velazquez and British Art at the Turn of the Century’, Visual Culture in Britain, vol.8, no.2, 2005, p.194.

Sickert, ‘Pictures of Actors’, 29 May 1897, in Robins (ed.) 2000, p.173. Sickert’s review is of an exhibition in which the Irving portrait was exhibited as the centrepiece of a survey of painting for the theatre and for music.

Reproduced at the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, http://www.nga.gov/fcgi-bin/timage_f?object=45879&image=8420&c= , accessed March 2011.

Walter Sickert, letter to Nan Hudson, c.July/August 1907; quoted and contextualised in Baron 2006, p.78, n.10.

See Andrew Stephenson, ‘Buttressing Bohemian Mystiques and Bandaging Masculine Anxieties’, Art History, vol.17, no.2, June 1994, pp.269–78.

Walter Sickert, ‘Topical Interviews. Mr Walter Sickert on Impressionist Art’, Sun, 8 September 1889 and Walter Sickert, ‘The New Life of Whistler’, Fortnightly Review, December 1908, in Robins (ed.) 2000, pp.57, 183.

Walter Sickert, ‘A Monthly Chronicle: The Whistler Exhibition’, Burlington Magazine, vol.27, no.148, July 1915, pp.169–70, in Robins (ed.) 2000, pp.388, 387.

See Anna Gruetzner Robins and Richard Thomson (eds.), Degas, Sickert and Toulouse-Lautrec: London and Paris 1870–1910, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2005, p.169.

Walter Sickert, ‘Preface’, in A Collection of Paintings by the London Impressionists, exhibition catalogue, Goupil Gallery, London 1889, in Robins (ed.) 2000, p.60.

Walter Bayes, ‘The Camden Town Group’, Saturday Review, 25 January 1930, p.100. It should be noted that although some members of the group lived close by in the Swiss Cottage/Hampstead area (Bevan at 14 Adamson Road and Manson at 184 Adelaide Road), others had no connection with the area. Lucien Pissarro lived in Stamford Brook, in west London, Drummond and Ginner lived in Chelsea, and Ratcliffe in Letchworth outside of the city. See Tate Britain 2008, p.14.

In this respect, Sickert’s early works on music hall themes had similarly been successful at integrating the formal experimentation of French avant-garde art with the native traditions and vernacular body language employed by late Victorian illustrators such as John Leech, Charles Keene and Alfred Bryan.

Walter Sickert, ‘The New English Art Club Exhibition’, Scotsman, 24 April 1889, in Robins (ed.) 2000, p.41.

Henry James, ‘London’, in Essays in London and Elsewhere, Books for Libraries, Freeport, New York 1922, p.27. See Judith R. Walkowitz, City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late-Victorian London, Virago, London 1992, pp.15–17.

William Rothenstein, Men and Memories: Recollections of William Rothenstein 1872–1900, Rose and Crown, London 1934, pp.167–8.

Raymond Williams, The Politics of Modernism: Against the New Conformists, Tony Pinkney (ed.), Verso, London 1989, p.45.

Reproduced at http://www.vangoghgallery.com/catalog/Painting/242/Interior-of-the-Restaurant-Carrel-in-Arles.html , accessed March 2011.

Charles Ginner, ‘Harold Gilman: An Appreciation’, in Memorial Exhibition of Works by the Late Harold Gilman, exhibition catalogue, Leicester Galleries, London 1919, p.5.

For the reception of Fry’s exhibition, see J.B. Bullen (ed.), Post-Impressionists in England: The Critical Reception, Routledge, London 1988, pp.93–131 and Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Modern Art in Britain 1910–1914, exhibition catalogue, Barbican Art Gallery, London 1997, pp.35–40.

Tate’s Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group catalogue argues that Gilman’s socialist principles and support for the working classes encouraged his interest in van Gogh’s scenes of labour and urban alienation and that, in relation to An Eating House, the work was derived from van Gogh’s Interior of a Restaurant at Arles 1888, then in a London private collection. See Tate Britain 2008, p.92.

See Julie F. Codell, The Victorian Artist: Artists’ Lifewritings in Britain, ca.1870–1910, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, pp.4–5.

Ford Madox Ford, ‘Modern Poetry’, published in the English Review in 1909 and later published in The Critical Attitude, Duckworth, London 1911, p.187. Quoted by Michael H. Levenson, A Genealogy of Modernism: A Study of English Literary Doctrine 1908–1922, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1984, p.108.

See Laurel Brake, Print in Transition 1850–1910: Studies in Media and Book History, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2001, pp.161–9, and Meaghan Clarke, Critical Voices: Women and Art Criticism in Britain 1880–1905, Ashgate, Aldershot 2005, pp.20–4 and 130–41.

See Mark S. Morrison, The Public Face of Modernism: Little Magazines, Audiences and Reception 1905–20, University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, Wisconsin 2001, p.6.

See Wallace Martin, The New Age Under Orage: Chapters in English Cultural History, Manchester University Press, Manchester 1967, pp.3–6. Martin highlights the significance of the various Education Acts in 1870, 1876 and 1880 in expanding literacy levels and generating socially broader reading publics. He notes the importance of changes in publishing linked to the New Journalism. He also emphasises how the ‘Little Reviews’ brought a new kind of cultural journalism to the fore with greater critical examination of literature, theatre and the visual arts that generated a very ‘modern’ kind of review writing and criticism. See Martin 1967, pp.10–13.

Robert Scholes’s introduction to the digital edition of the New Age; quoted by Ann L. Ardis, ‘The Dialogics of Modernism(s) in the New Age’, Modernism/Modernity, vol.14, no.3, 2007, p.417.

George Moore, ‘The Garret’, Saturday Review, 23 June 1906, p.785; quoted in Kenneth McConkey, The New English: A History of the New English Art Club, Royal Academy of Arts, London 2006, p.90.

However, it is worth noting that the increase in price, from the initial price of one penny per issue in 1907 to threepence in 1909 and then sixpence in November 1913, put it beyond the range of the working classes and perhaps signals a move towards exploiting the rising standards of lower middle class readers. See Ardis 2007, pp.432, ns.66, 717.

For a study of class and gender in the work of the Camden Town Group, see Valerie Webb, The Camden Town Group: Representations of Class and Gender in Paintings of London Interiors, Parker Art Press, Guildford 2006.

F.J.M., ‘The New English Art Club’, Speaker, vol.6, no.12, April 1902, p.106; quoted in McConkey 2006, p.94, n.30.

C. Campbell Ross or Gilbert Ramsay, ‘Introduction’, in Twentieth Century Art: A Review of Modern Movements, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1914, p.3.

http://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/opacdirect/3879.html . Two Mornington Cresecent Nudes are reproduced in Baron 2006, nos.332 and 334.

Sickert’s use of French titles for English nudes in interiors, such as Le Lit de Fer 1905 (The Queen’s College, Oxford) and Cocotte de Soho 1905 (private collection), apart from acknowledging that French was the lingua franca of the art world, signalled that many of these works were directed towards exhibition in Paris, notably to the Salon d’Automne to which both of these works were sent in 1905 and to which he was elected a Sociétaire in 1907. It is also significant that up to 1909 the main dealer for his work was Bernheim-Jeune in Paris, and many of the works completed after his return to London in 1905 were shown at that gallery in 1907, for example, Le Lit de Cuivre c.1906 (private collection), La Hollandaise c.1906 (Tate T03548) and Nuit d’été c.1906 (Ivor Braka Ltd) to exploit the growing market for modern nudes.

Frank Rutter, ‘Introduction’, in Post-Impressionist and Futurist Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Doré Galleries, London 1913; quoted in Barbican Art Gallery 1997, p.120.

Paul Jamot, ‘Le Salon d’Automne’, Gazette des Beaux-Arts, December 1906, p.484; translated in Tate Britain 2005, p.164.

Sir William Blake Richmond, letter to Robbie Ross; quoted in Matthew Sturgis, Walter Sickert: A Life, HarperCollins, London 2005, p.424.

Roger Fry, ‘Mr Walter Sickert’s Pictures at the Stafford Gallery’, Nation, 8 July 1911, p.536; quoted in Tickner 2000, p.19.

Roger Fry, ‘Mr Walter Sickert’s Pictures at the Stafford Gallery’, Nation, 8 July 1911; quoted in David Peters Corbett, The World in Paint: Modern Art and Visuality in England, 1848–1914, Manchester University Press, Manchester 2004, p.288, n.23.

Walter Sickert, ‘A Monthly Chronicle. Maurice Asselin’, Burlington Magazine, December 1915, in Robins (ed.) 2000, p.398.

Simon Watney, ‘Walter Sickert: Kendall, London and Manchester’, Burlington Magazine, vol.146, no.1221, December 2004, p.840.

Louis Vauxcelles, ‘La Vie Artistique: Exposition Walter Sickert à Felix Fénéon’, Gil Blas, 12 January 1907; quoted by Barnaby Wright, ‘Naked Realism: An Introduction to Walter Sickert’s Camden Town Nudes’, in Walter Sickert: The Camden Town Nudes, exhibition catalogue, The Courtauld Gallery, London 2007, p.19.