Introduction

Tate's collection is vast and different artworks resonate for different reasons with each individual. Your identity, your background, your perspective all shape how you respond to the art on display. Yet, if you're a person of colour this experience can be somewhat uncomfortable. What do you do when you look at a large collection of art from across the decades, but you cannot see yourself being represented?

Before the twentieth century, western art rarely depicted people of colour and when it did it was often tainted with the systemic racism that was prevalent. Can people of colour still find an identity in the startling whiteness of the collection?

Our Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Network, made up of a diverse range of voices of Tate staff, take a look at the artworks through the collection that have resonated with them. These are personal reflections that show a range of voices rarely given a platform. These speak less from a knowledge of art history, than from the act of experiencing art. Some of these thoughts pose difficult questions. Others validate and encourage and make it seem that a gallery that is representative of all might be possible after all.

Please be aware that this online guide includes explicit language.

Francis Barlow

Monkeys and Dogs Playing (1661)

Tate

The title of the piece is Monkeys and Dogs Playing, but they don’t look like they are playing to me. It’s interesting to note how lifelike the dogs are compared to the monkeys. When they analysed the canvas, they found the dogs had a layer of underpaint whereas the monkeys did not. This lends weight to the theory that the dogs were probably painted from life and the monkeys were copied from elsewhere. So why include the monkeys? Likely because they were seen as exotic and represented the strange and unusual. As an Australian-born Chinese, I am frequently made to feel strange and unusual too. A dominant viewpoint has determined I am not normal and common. But maybe they are just jealous – don’t we all want to be strange and unusual after all?

Interpretation by Amy Lin. Amy is a Project Manager at Tate and has been a Tate Guide since 2016. She is fascinated by the power and provocations of art and enjoys sharing her passion with the wider public.

THE CHOLMONDELEY LADIES C.1600-10

UNKNOWN ARTIST, BRITAIN

Unknown artist, Britain

The Cholmondeley Ladies (c.1600–10)

Tate

My chosen image is a Tate favourite, The Cholmondeley Ladies. Why? Try putting aside the popular take on the piece, the one that encourages you to enter into a childish game of spot the difference. Instead, direct your attention to the colours used in the painting: red, white and black. What these colours secretly convey is the purity of white blood, the preciousness of white womanhood, and an untold fear. Like the scene in Shakespeare's Othello, it speaks of fears of ‘an old Black Ram Tupping your white ewe' and creating 'the beast with two backs'. (Act 1 Scene 1).

Interpretation by Janet Couloute. Janet is a social work academic and PhD researcher in visual representations of madness and distraction in Western European artistic traditions. She has been a Tate guide since 2001.

DANCING SCENE IN THE WEST INDIES 1764-96

AGOSTINO BRUNIAS

Agostino Brunias

Dancing Scene in the Caribbean (1764–96)

Tate

Brunias's artistic work is known to depict idealistic and celebratory scenes of plantation life in the Caribbean. This could be viewed as ‘propagandist art’, distorting the harsh realities of slavery on the enslaved. It evokes a different set of racial and gendered lenses, namely, colourism. Colourism is the legacy of slavery, whereby people of colour with lighter skin are deemed more desirable and successful than those with darker skin. Brunias shows the lighter the skin, the freer you are. Darker skinned women of colour are still disproportionately affected by this phenomenon today.

Interpretation by Janine Francois. Janine is a Black Feminist Arts Educator whose practice is rooted in issues of social justice and intersectionality, education, participation and ‘art’. She is undertaking a practice-based PhD at Tate with the Schools and Teachers Team.

COLONEL MORDAUNT'S COCK MATCH C.1784-6

JOHAN ZOFFANY

Johan Zoffany

Colonel Mordaunt’s Cock Match (c.1784–6)

Tate

For most of the time the painting has been on display, the focus has been on how it has represented the morality of cockfighting not the morality of colonialism. In the painting, Europeans are the only ones seated on furniture and the way the European man is standing right behind a bent over Nawaab, is a strong image to represent the British domination and theft of India during Empire. The excluded histories that this painting carries with it need to be heard and maybe it is time to think about the humiliation a nostalgic sense of Empire can produce.

Interpretation by Hassan Vawda. Hassan is the Guides Coordinator at Tate and a co-chair of Tate’s BAME network. He is also an artist involved in programming and projects across multiple disciplines and an Aziz Foundation Scholar studying Community Development, looking at inclusion/exclusion within cultural and creative spaces, particularly faith-based creative expression.

THE FIELD OF WATERLOO 1818

J M W TURNER

The Field of Waterloo to me is about survival. A big portion of the painting is filled with darkness with only a few stains of light. One is in the foreground. It comes from a fire that lights up a pile of human bodies. Mostly dead and few alive. There is a sharp light in the background still unable to brighten the darkness of the night sky. Turner’s artwork reminds me of the most ancient tale of human history. The story of leaving your own home and never finding another one. The story of countless people who leave their war-torn lands, sail through the never-ending oceans, lose their loved ones to the battle with the water and never get accepted when they reach the so-called safe countries. The dead bodies piling up on each other makes me think of the souls of all the refugees who died in the sea or even when they survived the sea never got recognised as humans and forever got stuck behind borders. But there’s hope in the depth of all this darkness. The warmth of the torch shining light on the faces of those few survivors tells me of hope, of resilience and of the will to live. The Field of Waterloo tells me we will find peace; even if it’s only possible by searching through long nights of war.

Interpretation by Nikta Mohammadi. Nikta is a visual artist and filmmaker from Iran.

HEAD OF A MAN (?IRA FREDERICK ALDRIDGE) 1827

JOHN SIMPSON

If you’re white, you’ll never be able to understand fully what it means to be represented or what the importance of diversity is for a person of colour. You can only empathise, but never experience it for yourself. Recognising that limitation in one’s own emotional capacity and being sensitive to it is what it means to recognise your privilege. Imagine someone you know has lost someone close. You yourself have never had to mourn like they have. Everyone you know is healthy and well. You have no idea what the emotional experience is like. You can only sympathise, but you can’t fully relate. Head of a Man means so much, because for a person of colour coming into Tate Britain, it is one of the few paintings from history that recognises that people of colour exist. It is a sudden flash of representation, small and sometimes overwhelmed by other artworks, but significant nonetheless. It says, you exist. You always have. When everything around you validates your existence as a white person, you’ll never know how this feels. Just understand it’s important. This one artwork has given a person of colour the sense that they belong in a world that is constantly telling them they don’t.

Interpretation by Nick Virk. Nick is a writer, wannabe Bollywood director, Assistant Producer and co-chair of the LGBTQ+ and BAME Networks at Tate.

PUNCH OR MAY DAY 1829

BENJAMIN ROBERT HAYDON

Benjamin Robert Haydon

Punch or May Day (1829)

Tate

This painting reminds me of a lecture at university where we looked at a series of nineteenth-century paintings depicting black figures. The lecturer told us about a figure in British art commonly referred to as a ‘Reynolds’ Black’ - a figure of Afro-Caribbean descent, always depicted in relation to a white counterpart. The white figures in this painting, like nearly all of its contemporaries, are the centre of attention; the boy in blackface supposedly performing blackness attracts the viewer’s gaze, while the black footman standing on the carriage is easy to miss. I prefer trying to find these figures whenever I look back at these paintings - trying to locate a narrative that was supposed to be hidden.

Interpretation by Esra Unal. Esra is a Digital Marketing Intern at Tate as well as an English student in London specialising in British Black and Asian Literature.

A BLACK MODEL C.1830-40

UNKNOWN ARTIST

Unknown artist, Britain

Unknown Man (c.1830–40)

Tate

As one of the earlier representations of a black subject in the collection, I want to know more about the history of this painting. The identity of the young man is unknown. Who is the sitter? The artist who painted this is also unknown. Who painted it? The work was purchased in 1942. Who acquired it? Who was it bought from? And why has it only been on display twice? Do you know?

Interpretation by Leyla Tahir. Leyla is a creative producer and ex-Tate Collective member, currently working in Marketing at Tate.

THE ANNUNCIATION 1892

ARTHUR HACKER

Arthur Hacker

The Annunciation (1892)

Tate

A young girl, Mary, stares right through The Annunciation into the eyes of the observer. An angel is floating behind her and a vase next to her bare feet. Her body is covered with a transparent air-like material. Infrared photography reveals there was a woman wearing a headscarf behind the young girl. The softness of the figures, decorative feel of the trees and flowers in the background, Mary’s attire and the invisible ghost of the woman with the headscarf reminds me of painting traditions of the Middle East. The first time I saw this painting I travelled back in time to when I was 9 and celebrated my coming of age. Wearing a white Chador*, there is a picture of me looking into the camera with eyes carrying a similar look to those of Mary in Hacker’s painting; a hidden defiance, a fear of unknown-land of adulthood and an excitement for the pleasure and the pain waiting ahead of me.

*Chador: an open garment worn by some women in Iran, Iraq and other Shia regions.

Interpretation by Nikta Mohammadi. Nikta is a visual artist and filmmaker from Iran.

HIS HIGHNESS MUHEMED ALI, PACHA OF EGYPT 1841

SIR DAVID WILKIE

Sir David Wilkie

His Highness Muhemed Ali, Pacha of Egypt (1841)

Tate

I started at the beginning and walked through 300 years. Past five Elizabeths, four Jameses, four Thomases, a couple Henrys, a few Johns, two Williams, an Anne, a Margaret, Bartholomew, Christopher, George, Neil, Helena, Jacob, Madeleine, Charles, Samuel and Susannah. Then I found him. Mehmet Ali. The first familiar name. The same as my uncles. The first familiar look: long beard, pointed slippers, loose trousers, red fez. Tucked in a corner with Millais and hung next to a field of corn and hay. The first portrait in 300 years I looked at and felt connected to. Mehmet Ali, Your Highness Muhemed Ali, Pacha of Egypt, I don’t know your story, I don’t know much about who you are, but I look at you and feel like I see a bit of me. I’m glad that after 300 years, you’re here.

Interpretation by Leyla Tahir. Leyla is a creative producer and ex-Tate Collective member, currently working in Marketing at Tate.

AKUA-BA 1931

JOHN SKEAPING

John Skeaping

Akua-Ba (1931)

Tate

It looks nothing like an Akua'ba, a figurine traditionally used as a fertility aid in Ghana. To me this piece is all about power dynamics. About who has the power to define cultural value and tell stories. The sculpture was produced at a time when Ghana was being occupied by the British. Also coinciding with a period of art history when European artists were fetishising 'primitive' artworks from Africa, Asia and Pacific Islands while happily chopping and changing bits of them to include in their work, which was then hyped by the art world (hi Picasso ... ) So yeah, this piece pisses me off.

Interpretation by Arenike Adebajo. Arenike is a London-based writer who has worked with Tate Collective, the Guardian, gal-dem and FLY Cambridge.

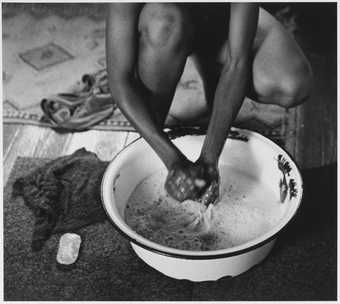

UNTITLED FROM THE SERIES REFLECTIONS OF THE BLACK EXPERIENCE 1986

SUNIL GUPTA

Sunil Gupta

Untitled from the series Reflections of the Black Experience (1986, printed 2010)

Tate

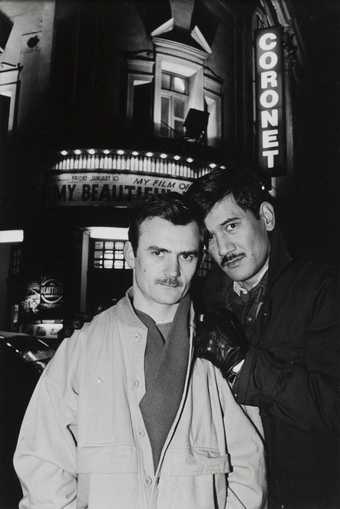

When I first saw this photograph, I cried. Every time I see it, it makes me shudder with such mixed emotions. Here is a gay couple, one white, the other South Asian, standing outside a cinema playing My Beautiful Laundrette. Looking at LGBTQ+ history in this country, people of colour have always been sidelined. Here, I see someone like me, brown and queer, documented in history. I walk the streets feeling it’s subversive to be like me. I’m new. People like me haven’t existed before. People of colour were too scared to come out of the closet because of cultural barriers. And yet here, I get a sense of the generations who have paved the way for me. I cry with happiness. And I cry with sadness. When will stories like mine be told? How many more times will my existence be erased by the prevalence of whiteness, the undisputed norm? When will it no longer be subversive to be brown and queer? When will My Beautiful Laundrette be just one of many stories that validate me? Of course, I have realised I have to write those stories myself - a battle so many reading this will never have to endure.

Interpretation by Nick Virk. Nick is a writer, wannabe Bollywood director, Assistant Producer and co-chair of the LGBTQ+ and BAME Networks at Tate.

NO WOMAN, NO CRY 1998

CHRIS OFILI

Art didn’t seem like it was for someone from my background until I saw this painting by Chris Ofili and instantly felt connected. Your first thought might be that the painting is big, bold and beautiful just like Doreen who is being depicted in the painting (and therefore suddenly given the responsibility of representing all the black women in our community). It is also very colourful and so can easily be appropriated through these aspects. However, the painting is cleverly underpinned by the title No Woman No Cry, a famous song by Bob Marley that is supposed to be a comfort to the struggles of black women. Everyone knows the song but not everyone knows the struggle, just like it is hard to see that every drop of Doreen’s tears contains a small picture of her son Stephen Lawrence, who was killed in a racist attack. A woman crying is a universal symbol but the fact that she is a black woman crying is so prevalent in our community. On viewing this painting, I instantly understood what it meant. This proves that there needs to be more black art in our galleries if the art world is serious about reflecting the diversity of Britain.

Interpretation by Samara Straker. Samara is an Intern for Tate Digital, interested in writing and film.

HANDSWORTH SONGS 1986

BLACK AUDIO FILM COLLECTIVE

The film is a montage of archival footage put together by the film collective - there are news clips from the 1984 Handsworth Riots, men singing on the HMS Empire Windrush and images of the local community discussing the reasons behind the violence - all tied together with an ominous narrative voice. The mantra of the film - 'there are no stories in the riots, only the ghosts of other stories' - shows us that the riots came as a result of a long history of systematic injustice. The carefully-angled camera shots and repeated images of chains prove this, exposing the distorted media representations and police brutality that black people faced.

Interpretation by Esra Unal. Esra is a Digital Marketing Intern at Tate as well as an English student in London specialising in British Black and Asian Literature.

THE CARROT PIECE 1985

LUBAINA HIMID

Lubaina Himid CBE RA

The Carrot Piece (1985)

Tate

© Lubaina Himid, courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London

I love this piece! It’s such a funny send up of the relationship between white 'liberal' institutions and black artists. All the more striking as this is one of the few works by a black woman on display at Tate. Lubaina Himid was exploring how these institutions often made tokenistic and patronising attempts to include black people in their programmes and it’s wild that we’re still resisting the same dynamics today.

Also, what an iconic side eye. The woman is looking back disdainfully at the white man, she leans forward, arm wrapped protectively around her possessions. It says a lot about the incredible resilience and self-reliance of black artists and collectives, who have always been able to create and support each other without validation from institutions who leech off people of colour for cultural capital. Like Solange says, ‘This shit is from us/ Some shit you can’t touch.’

Interpretation by Arenike Adebajo. Arenike is a London-based writer who has worked with Tate Collective, the Guardian, gal-dem and FLY Cambridge.

Meem Two 1967

Anwar Jalal Shemza

Anwar Jalal Shemza

Meem Two (1967)

Tate

My love for text-based art was amplified when I saw Meem Two by Anwar Jalal Shemza at Tate Liverpool in 2018. The artwork presented me with an op-art piece based on the abstraction of Arabic text. Reading this work felt natural. It was instinctual for me to use the cultural capital that I had gained at art school alongside the cultural awareness I gained as a child attending Arabic lessons at the mosque. I grew up seeing Zero to Nine by Jasper Johns in galleries. Meem Two showed me the possibility for the abstraction of text in contemporary art to expand beyond roman alphabets and for it to be recognised in the Western art world canon.

Interpretation by Sufea Mohamad Noor. Sufea is the Development Assistant at Tate Liverpool. She is interested in postcolonial discourse in the context of contemporary art and recently completed her MA in Art Gallery and Museum Studies at The University of Leeds.

Caribs' Leap/ Western Deep 2002

Steve McQueen

Sir Steve McQueen

Caribs’ Leap/Western Deep (2002)

Tate

© Steve McQueen. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Marian Goodman Gallery

How much do we know about the history of the West-Indies? In Caribs' Leap / Western Deep, Steve McQueen delves into the history and culture of native communities. They are two films, shown side by side, always in dialogue with each other. In Carib’s Leap, audiences witness the terrible events of 1651 in Grenada. 1651 saw the last Caribs of the island jump off a cliff near the town of Sauteurs (now known as Caribs' Leap) rather than to surrender to the French and to be deprived of their freedom. Western Deep also shows a fall. Miners, who are barely visible by the red lights of their helmets, descend into the deepest mine in the world, Tau Tona in South Africa. The miners have lost their humanity. They are exhausted, passing each other a thermometer to take their temperature without any other communication.

Both films show the hardships imposed in the on the native peoples of Grenada and South Africa. As someone who belongs to a minority that has experienced so many struggles in the past and continues to do so in the present, I believe that films such as Caribs' Leap and Western Deep should be seen for the messages they carry. My parents also came from the West Indies and almost sixty years on still little is known about West-Indian cultures and history. Caribs' Leap and Western Deep can enlighten us all, and perhaps to make us rise rather than feel neglected, mirroring that awful feeling of descent that we see in McQueen’s films.

Interpretation by Robert Raynard. Robert is a Visitor Assistant at Tate.

The Generosity 2010

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

The Generosity (2010)

Tate

The Generosity rewards slow looking: of taking a step back, perhaps walking to another part of the gallery and returning. On second, third, fourth glance, you will see something new. Part of its generosity to us as viewers is that it asks us to step out of what we think we already know, and to perhaps think again. These two subjects do not exist: Yiadom-Boakye states that all the figures we see in her paintings are imaginary. With that comes a level of freedom – they can be anyone we want them to be. There aren’t many clues on offer: the two men are in a state of undress, putting on socks. It is hard to see where they are, or what they might have been doing moments prior. It is also difficult to decipher what these two men mean to each other. Her brushstrokes relay a sense of urgency: Yiadom-Boakye often paints her portraits in one day. The colours – dark with grey, brown and green hues – mean we must try and imagine what kind of world they exist in. There are so many stories to be told and here, the story seems to change every time. Generosity from a painter to the viewer is to offer us a little more each time, so it unravels into something new.

Interpretation by Vanessa Peterson. Vanessa is an editor, photographer and occasional writer currently working as a Research Producer at Tate. Her research interests focus on the relationship between the word and image, especially representations of race and gender.