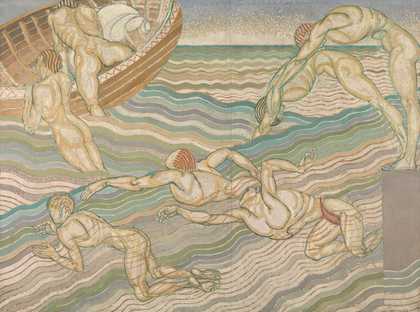

Glyn Warren Philpot

Repose on the Flight into Egypt (1922)

Tate

Glyn Philpot struggled to shake off his early typecasting as a painter of flattering society portraits. Repose on the Flight into Egypt is arguably the best of several idiosyncratic ventures into religious territory. Journeying into exile to evade Herod’s assassins, the Holy Family huddle for shelter by a colossal fallen statue. A curious sphinx, fauns and centaurs – mythical creatures associated with the pre-Christian Mediterranean world – have quietly assembled to witness the newly arrived Christ. The mysterious image might almost be titled ‘The Adoration of the Monsters’.

Hybrid creatures often stalk the realms of queer imagination. Philpot’s mentor Charles Ricketts (1866– 1931) illustrated a lavish edition of Oscar Wilde’s coded, erotic poem The Sphinx. Vaslav Nijinsky became a queer icon through his performance as a faun. Centaurs and minotaurs still crop up both in gay erotic comics and in queer contemporary art. Such creatures of the wilds embody the promise of sensuality untrammelled by human social conventions. During the Italian Renaissance of the fifteenth century, these sexy, classically-inspired hybrids returned to the stage of Western art, coinciding with a rediscovery of the idealised male nude.

Many gay aesthetes – including Wilde, Ricketts and Philpot – felt strong affinities for Renaissance art, and Repose on the Flight into Egypt was actually painted in Florence, cradle of the style. During his Italian stay, Philpot made sure to visit Orvieto Cathedral, where the impressive parade of nudes in Luca Signorelli’s frescoes are ever popular with gay tourists. A figure borrowed from Signorelli can be found in the polyamorous queer triad at the left of this painting (directly behind a stridently phallic cactus).

This text is an extract from A Queer Little History of Art, written by Alex Pilcher.