Pacita Abad

European Mask (1990)

Tate

Contents

Introduction

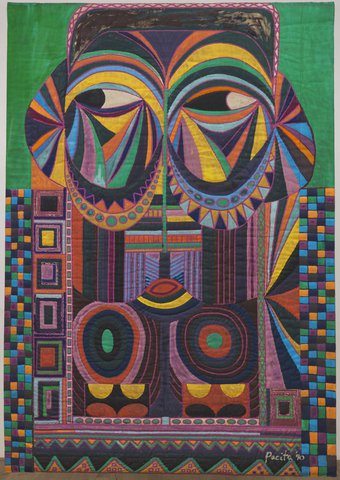

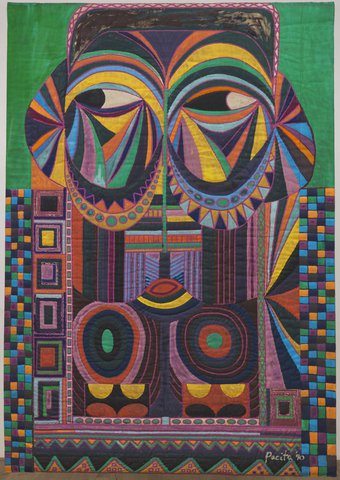

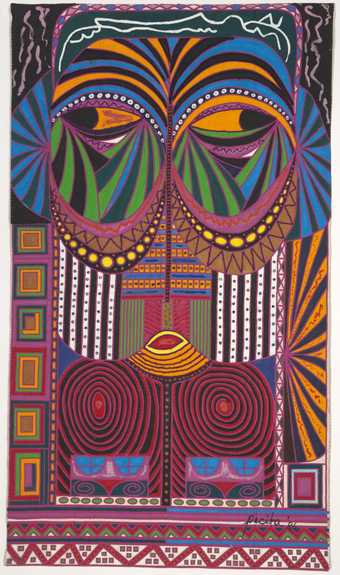

Large darting eyes stare out from a colourful pattern of geometric shapes. European Mask, painted in 1990, is one of a series of mask paintings by artist Pacita Abad. Banner-like in its construction and with a quilted surface, European Mask is an unusual painting. It is also an intriguing one: despite its title, the artwork’s connection with Europe is not immediately obvious.

Artist Pacita Abad said about her work: ‘my paintings tell the stories of people that I have met and talked to along my way’. What is the story behind European Mask?

Who is Pacita Abad?

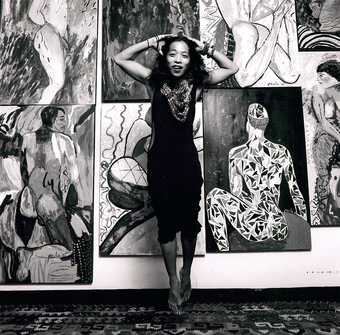

Wig Tysmans Pacita Abad © Courtesy of the Pacita Abad Art Estate

Key to understanding European Mask is knowing something about the artist who made it.

Pacita Abad was born in 1946 in Batanes, a small island at the northern most point of the Philippines, and grew up in Manila. In 1969 she left the Philippines and moved to San Francisco. Although she had originally planned to become a lawyer, her experience of living in the vibrant ‘hippie’ district of San Francisco, and meeting artists, musicians and other free spirits there, sowed the seeds for a very different life than her planned law career.

America sort of gave me my independence … It gave me freedom to do a lot of things. There were no family members to say ‘don’t do this’; ‘come home early’ or ‘come home this time’ so in a way I was free to choose what I wanted to do.

Pacita Abad

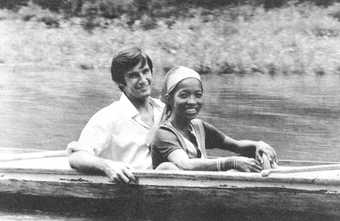

In 1973 Abad spent a year travelling around Asia with her boyfriend Jack Garrity (whom she later married). Starting in Turkey, the couple hitch-hiked overland through Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Taiwan and Hong Kong. Their journey ended in the Philippines where she spent two months exploring and rediscovering the beauty and cultural heritage of her homeland.

Jack Garrity and Pacita Abad c1974 in Pangasinan Falls. Photo by unknown photographer © Courtesy of the Pacita Abad Art Estate

This interaction with different cultures and people had a huge impact on Pacita Abad’s life and future plans. She decided to pursue a path towards becoming a painter. The journey was also the beginning of a life of travel and exploration. Jack Garrity’s work as a development economist took him to different countries around the world, offering new and diverse environments for Abad to explore. She painted, gathered local materials and researched traditional artistic techniques in the many countries that they lived in.

Across the sea... and under the sea!

Wig Tysmans Pacita Abad © Courtesy of the Pacita Abad Art Estate

Pacita Abad was an experienced scuba diver. In the 1980s she created a series of paintings inspired by the extraordinary creatures, plants and colours that she saw in her underwater explorations around the Philippine islands.

These were shown in an exhibition Assaulting the Deep Sea in the Ayala Museum in Manila in 1986. Abad wore her scuba diving gear to the opening!

A closer look at European Mask

European Mask is one of three Masks by Pacita Abad in Tate’s Collection. The Masks are part of her Bacongo series, inspired by masks made by the Kongo people of Central Africa.

MCAD Manila exhibition installation - photo by Pioneer Studios © Courtesy of the Pacita Abad Art Estate

European Mask is over 2.5 metres high and looks like a wall hanging or banner rather than a painting. Artists usually stretch canvas over a rigid frame, called a stretcher, in order to paint on it. But Abad painted on the canvas unstretched. She then stitched and padded the canvas creating a soft undulating surface. Her stitching technique can be clearly seen in this photograph of the back of another mask from Pacita Abad’s Bacongo series.

Pacita Abad Bacongo VIII (rear view) 1980 © Courtesy of the Pacita Abad Art Estate

Although the construction of European Mask is unusual for a painting, its patterns and details were made using conventional techniques – acrylic paint and silkscreen.

The Masks: sources and starting points

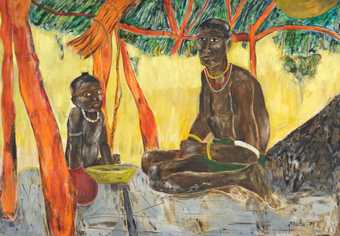

Pacita Abad Father and Son 1979 © Courtesy of the Pacita Abad Art Estate

Pacita Abad first began making mask paintings in the late 1970s.

In 1979 she travelled to Africa with her husband, who was working for an American aid organization. They visited Kenya, Sudan, South Sudan and the Congolese border. Abad painted the places they visited and the people she met.

Cross-cultural encounters

Pacita Abad was not the first artist to paint abstracted figures inspired by the forms of African art. In the early twentieth century many European artists were beginning to experiment with abstraction, and looked to non-Western art for ideas.

Pablo Picasso is celebrated in art history as being one of the inventors of abstraction. His painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon 1906-7 is seen as central to the development of his abstract style. The abstract mask-like faces he added to the bathers in the painting were taken directly from African carving, as well as from Iberian sculptures. Amedeo Modigliani painted stylised portraits with long thin faces and small mouths, placed low in their features. But these distinctive portraits are rarely discussed in relation to the Baule masks from the Ivory Coast that were the source of Modigliani’s stylised approach.

Mask made by an unknown artist of the Baule people, Côte d'Ivoire © The Trustees of the British Museum). released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska (1918)

Tate

Art is for other people. It’s not just for yourself.

Pacita Abad

The inspiration that Pacita Abad took from cultures around the world came from the perspective of being a Filipino immigrant to America, and her involvement with other non-white immigrants, marginalised communities and refugees.

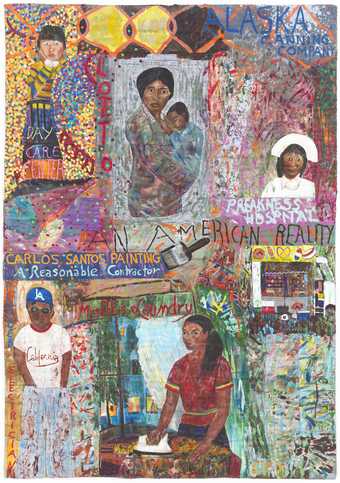

Her Immigrant Experience series, painted in the early 1990s depicts the lived experience and issues faced by immigrants in America.

Pacita Abad I thought the streets were paved with gold 1991. Photo by Max McClure © Courtesy of the Pacita Abad Art Estate

Her encounters with the artistic traditions of the countries she visited were often in the context of traveling with aid and development workers. As her nephew, artist and writer Pio Abad, suggests in his Tate Etc article 'Entangled Modernities':

These experiences shaped Abad’s empathy for the different indigenous communities that she encountered throughout her life and instilled a sense of care in her handling of their traditional motifs and materials.

Pio Abad

Pacita Abad’s use of techniques and stylistic forms gathered from her travels, acknowledged the cultures that influenced her, and reflected their stories and struggles. Abad’s paintings are a record of the communities that she encountered and the people she met.

Techniques and Materials

At around the same time that Pacita Abad was experimenting with abstract forms, she also began to develop a new technique. Again, she was inspired by her travels.

In 1979 when Abad was in Africa, she ran out of the art supplies that she had brought with her. So she started to paint on the rough hessian sacks used by aid organisations to transport flour and grain to refugees, priming them using a mix of flour and water. This was perhaps her first step in abandoning conventional painting materials and processes, and exploring the possibilities of different surfaces and textures.

Portable paintings

In 1974 Pacita Abad had visited a Tibetan refugee camp in Nepal and was fascinated by the Thangka tapestries she saw there. The stories they told, the colours, and the scale attracted her; but she was also interested in the portability of the tapestries. That these artworks could be rolled up like quilts and carried away, fitted with the nomadic life that Abad was herself starting to lead. She realised that she could potentially make portable paintings that did not need to be stretched over a bulky frame.

Trapunto

In around 1980 Pacita Abad started to make stitched and padded canvases. The process was rooted in an Italian quilted embroidery technique called trapunto.

Although Abad adopted the Italian name ‘trapunto’ for her padded paintings, she made the technique very much her own. Many of her trapunto works, including the other two Masks in Tate’s collection, are not only painted, but are also embellished with fabrics and objects stitched together to create intricate patterns.

Trapunto allowed her the freedom to continually experiment.

Pio Abad

Travels and textiles

Pacita Abad had always been an avid collector of traditional textiles. On a visit to Guatemala in 1976 she gave all her clothes to local women and filled her suitcase with colourful hand-woven güipil blouses and dresses she bought at the village markets there. She not only wore the vibrant fabrics that she gathered on her travels, but began to incorporate them into her art.

She also experimented with the traditional techniques that she encountered. Textile processes including batik, mirror-work, tie-dye and macramé became part of her artistic process.

My works are like inspirations [from] the many places that I visited and the many cultures that I see… I would go to Burma and I would pick up the gold thread embroidery or I would go to India and pick up the mirror embroidery or Nigeria, Africa with the tie-dye and then all of these things I try to put it in my work

Pacita Abad

Colourful, hand-worked fabrics, buttons, shells, bits of glass, mirrored sequins and all sorts of other things (including plastic fruit and even empty tubes of paint); were stitched and layered onto the painted, padded surfaces of her canvases, creating a unique visual language.

Pacita Abad The sky is falling, the sky is falling (detail) 1998. Photo by Max McClure © Courtesy of the Pacita Abad Art Estate

Pacita Abad Korean shopkeepers (detail) 1993. Photo by Max McClure © Courtesy of the Pacita Abad Art Estate

Home truths: stitching and colour

As well as taking inspiration from the countries she visited, Pacita Abad was also inspired by her childhood and her homeland.

Sewing was a traditional part of family education in the Philippines. Her trapunto paintings were all hand sewn, each taking around 6-8 weeks to complete. Abad usually worked alone, making several at once, though sometimes she brought in family members to help her.

The vivid colour that she filled her paintings with is also something she attributed to growing up in the Philippines. At art school in New York she was asked (on a grey November day) about the ‘wild’ colours in her paintings. She replied: ‘These were the colours I grew up with – Chinese red, yellows and oranges – I can’t help it, I have to paint with these colours!’

Unmasking the masks

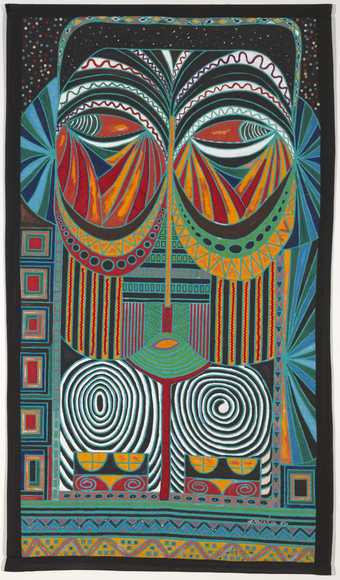

At first glance the three masks in Tate’s collection look fairly similar. All are stitched, quilted canvases with images of brightly coloured and patterned mask-like faces.

Take a closer look. Do you notice anything about the patterns in European Mask compared to the two Bacongo masks?

Pacita Abad

European Mask (1990)

Tate

Pacita Abad

Bacongo III (1986)

Tate

Pacita Abad

Bacongo VI (1986)

Tate

The patterns of European Mask are formed from more regular geometric shapes, and the areas of colour are flatter. The all-over meandering patterns of Bacongo III and Bacongo VI are closer to the patterns and mark making seen in African sculpture.

Now compare the materials used to make the images. Acrylic paint and silkscreen (conventional western techniques) have been used for European Mask. The two Bacongo masks have fabrics and other materials including plastic buttons, ribbons, and glass attached to their surfaces.

Why do you think Pacita Abad chose the patterns and materials for European Mask?

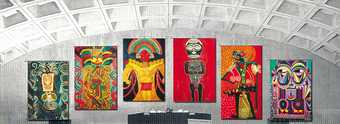

Masks from Six Continents

In 1990 Pacita Abad was awarded a major commission to show her work at the Metro Center in Washington DC. She exhibited an installation of six monumental trapunto paintings called Masks from Six Continents. Each of the six masks represented a continent, reflecting, according to the artist, ‘all the different people I see on the train’. The installation included a version of European Mask.

Pacita Abad Masks from Six Continents, a 3-year installation at Washington, DC Metro Center © Courtesy of the Pacita Abad Art Estate

Of the six masks, European Mask is the only one that is generically titled with the continent’s name. The titles of all the other masks reference the particular cultures that inspired their shapes, patterns and techniques: Africa is represented by a mask titled Kongo; North America is represented by Hopi Mask; and South America is represented by Mayan Mask.

In using titles that reflect the cultures that inspired them Abad acknowledged that these continents are made up of a rich and vibrant mix of different peoples and traditions. This is very different from the European approach to art and art history where ‘other’ non-Western cultures are often summarised as ‘African’ or ‘Asian’. With the titles of her masks, Abad seems to consciously counter this Eurocentric viewpoint. She suggests that it is in fact Europe that is culturally uniform, lacking the rich variety of different peoples, traditions and cultures seen within other continents.

‘You gotta tell them sometimes!’

As well as responding to the experience of marginalised people, Abad wanted to celebrate different artistic traditions and indigenous art forms. She was frustrated by Western-centric attitudes in the art world that often dismissed textile art forms as ‘craft’ and did not take them seriously.

In an interview with journalist Yvette Sitten (‘Pacita Abad: Spirited Faces’) Abad recounts the story of a curator from New York coming to visit her studio in Washington. Because Abad’s paintings include a range of materials such as buttons and yarn, and were made using stitching techniques, the curator suggested they were not ‘high art’. Abad’s response was:

You better wake up because a lot of people are coming from Asia, from Latin America, they’re coming to America and they’re bringing their artwork with them and much of this incorporates a lot of materials you haven’t even imagined. You have to re-learn your studies because these days art can evolve in so many different ways in so many different processes, and techniques.

Abad added, with a smile: ‘you gotta tell them sometimes’. The curator went on to organise an exhibition of the work of immigrant artists including Vietnamese, Cambodian and Thai artists.

Making the world a little better

Through the unique visual language that Pacita Abad developed she connected the world. As well as painting her experiences of the different cultures she encountered, and the lives of the people she met, these cultures are literally embedded into the materials and techniques used to make the work. In reflecting the lives and experiences of other people, she also reflected the story of her own life.

In a statement written for the Brooklyn Museum, Pacita Abad said that as an artist she wanted to make people aware, make people think and make people smile.

In European Mask we see all of these aims at play. The juxtaposition of the painting’s title with a mask-like image inspired by the sculpture of the Kongo people, makes us question what we are looking at. It makes us think about our art history and be aware that so much of it is told from a Western standpoint. We also think about technique, and realise that paintings don’t have to be stretched flat over a rigid frame, (and through exploring her other artworks we appreciate that all sorts of textile techniques can be used to make art). And the scale, dazzling patterns, and vibrant colours of European Mask, like so many of Pacita Abad’s beautiful, intricate, artworks, make it a joy to look at.

I feel like I am an ambassador of colours, always projecting a positive mood that helps make the world smile.

Pacita Abad

Paul Tanedo Pacita Abad © Courtesy of the Pacita Abad Art Estate

Research supported by Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational in partnership with Hyundai Motor