Pacita Abad

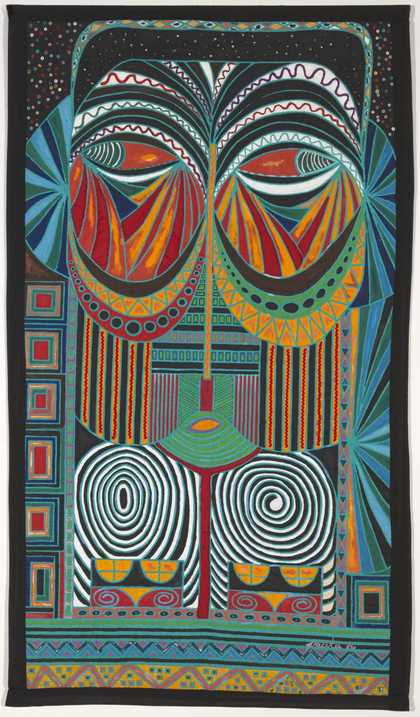

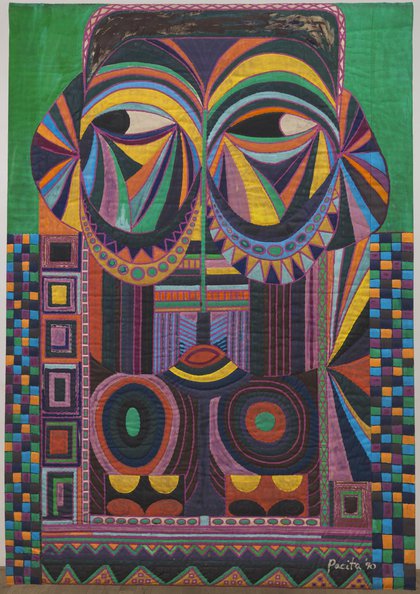

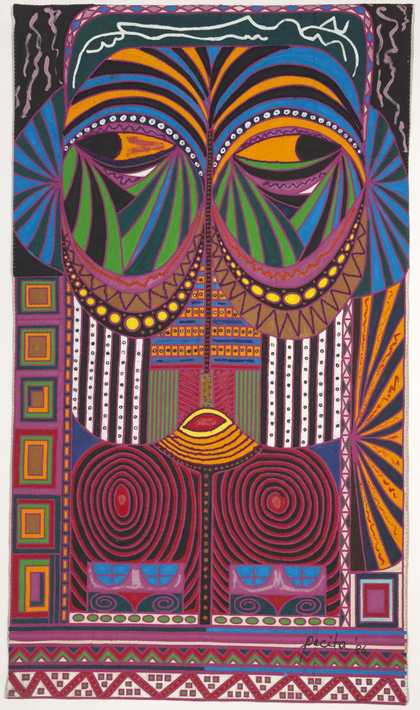

Bacongo III (1986)

Tate

Pacita Abad (1946–2004) first visited the African continent in 1979. Accompanying her husband, a development economist, on a series of aid missions, she travelled to Kenya, Sudan, South Sudan and the Congolese border. It was during a four-month stay with fellow Filipinos, working with UNICEF in the town of Wau in South Sudan, that Abad started developing her paintings based on tribal masks and figures – using relief sacks primed with flour and water as her canvases after exhausting the materials that she had brought with her.

In the late 1970s, Abad started working on her Bacongo series, inspired by the Kongo masks she had come across during her missions. Over a period of ten years, Abad produced eight Bacongo paintings, using a technique she called trapunto, which involved painting and screenprinting on unstretched canvas, quilting and padding the painted canvas, embroidering the surfaces by hand and then embellishing them with different materials: ikat fabric, raffia textiles, seashells, sequins and rick-rack ribbons, to name a few.

Abad’s omnivorous approach to material was rooted in her immersion in different communities and different cultures, an immersion deeply informed by her upbringing in the remote island of Batanes in the Northern Philippines, her identity as a brown American immigrant, and an itinerant life surrounded by aid workers and economists. These experiences shaped Abad’s empathy for the different indigenous communities that she encountered throughout her life and instilled a sense of care in her handling of their traditional motifs and materials.

When one of the works from the Bacongo series appeared as part of Masks from Six Continents, Abad’s monumental commission for the Washington, D. C. Metro Center in 1990, it had been reworked into the piece entitled European Mask 1990. The general designation of ‘European’ in the title appears pointed, in contrast to the more specific attributions to the other works in the series, such as Hunaman for Asia, Hopi Mask for North America, Kongo for Africa and Mayan Mask for South America – the substitution offering a vibrant riposte to the appropriation of so-called primitive art by European artists and the Western tendency to summarise Africa as a monolithic culture.

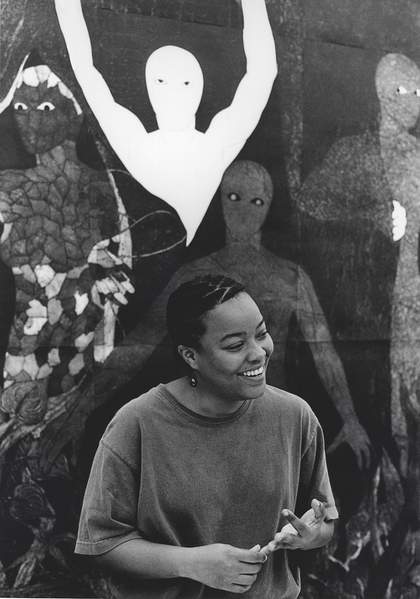

Pacita Abad in her studio with the Masks from Six Continents commission for the Metro Center, Washington, D.C., 1990

© Courtesy of the Pacita Abad Art Estate, photo: Paul Tanedo

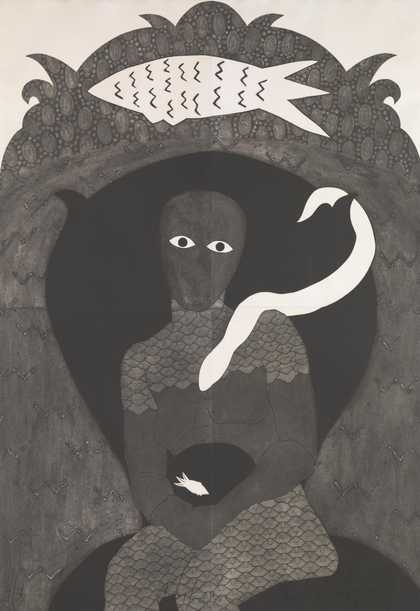

Around the same time that Abad was working on European Mask, Belkis Ayón (1967–1999) was asserting the African roots of Cuban culture through large-scale prints depicting the Abakuá Secret Society, an all-male belief system that traces its roots to Nigeria and Cameroon, and which entered the country through the slave trade. The absence of figuration in Abakuan iconography allowed Ayón to create her own visual language using collagraphy, a printmaking technique in which different materials are applied to a hard surface, creating a textured plate which is then inked and printed – an approach she adopted due, in part, to the scarcity of materials in Cuba following the fall of the Soviet Union.

A central figure in her work is Sikán, the only woman in Abakuan legend, who was put to death for revealing the secrets of the religion. The Supper 1991, a six-part collagraph that weaves Abakuan myth with Christian imagery, presents Sikán as a stark, white figure flanked by dark, patterned bodies, rendering her significant but isolated. Ayón saw Sikán both as an allegory and an alter ego, a way of both literally and metaphorically centring the female struggle and constructing her own identity within her work. As a black Cuban woman, Ayón’s devotion to creating work about the all-male religion was striking in its capacity to embody the mystique of a belief system from which she was excluded – offering both a celebration of unheralded Afro-Cuban traditions and a critique of Cuban patriarchy.

Belkis Ayón at the Havana Galerie, Zurich, August 1999

© Belkis Ayón Estate, Havana, Cuba, photo: Werner Gadliger

The works and the lives of Pacita Abad and Belkis Ayón present a stark contrast to the way the work of Western artists, such as that of Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920), has previously been disassociated from the rich traditions it has drawn from. When writing this text, I discovered that Modigliani was influenced specifically by the wood carvings of the Baule people from the Ivory Coast, adopting the distinct narrow forms of Baule masks, with mouths placed unnaturally low on the face, in his own figures, as evident in works like Madame Zborowska 1918 and Head c.1911–12. Faced with the task of reimagining the history of art, it is essential to recognise the impact of the dispossessed and colonised, and to celebrate artists who have devoted their lives to such an endeavour. Abad and Ayón’s art, and their commitment to the marginal societies depicted in their work, are important guideposts in this reimagining.

Pacita Abad's Bacongo III 1986, Bacongo IV 1986 and European Mask 1990 were purchased with funds provided by the Asia-Pacific Acquisitions Committee in 2019. Belkis Ayón's The Supper 1991 was lent by the Tate Americas Foundation, courtesy of the Latin American Acquisitions Committee and The Cowles Charitable Trust in 2018. Artworks by Abad and Ayón are on display as part of Whose Tradition? at Tate Liverpool, until January 2022.

Pio Abad is an artist who lives and works in London.