The sun is bright in Wolfgang Tillmans’ studio, warming and expansive. Outside, a commuter train sends arcs of light across the roofs of the sur rounding industrial landscape as it shakes its way on to the City of London. I am here to look through the artist’s working copy of his book, if one thing matters, everything matters.

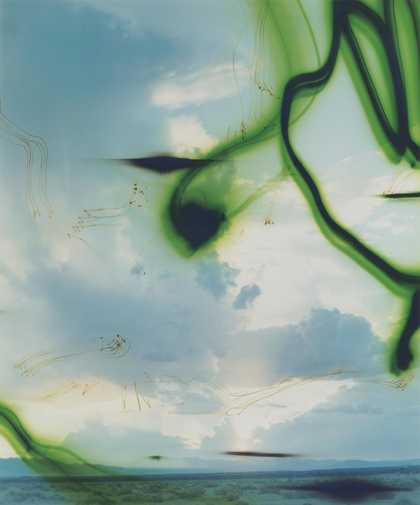

In making this book, Tillmans has revisited every film he has ever exposed, every work he has ever made, compiling more than 2,300 pictures and placing them into a strict grid. Their ordering is ostensibly chronological, but based upon two systems: the year in which the photograph was taken, and then, within each year, the order in which the photographs became ‘works’. Some pictures took time to be accepted by Tillmans in this way and thus occur out of the sequence of their taking. There is a general sense of an historical flow, but readers are likely to swirl through eddies of time and find themselves moving back upstream on occasion. Each image is held within a six-centimetre square; each matters as much as any other, no more, no less. The uniformity of the layout emphasises the extraordinary diversity of the pictures: portraits of friends and intimate revelations of great tenderness to experiments with abstract forms, tendrils of light curling around the blank paper or across empty landscapes.

Wolfgang Tillmans

Lily & Oak 1999

Photograph

Courtesy Maureen Paley Interim Art, London © Wolfgang Tillmans

There is so much here in this book, and so much that is different, that it might be difficult, at first, to see how it all comes together, how to make sense of it. I look up and around Tillmans’ studio. Exotic flowers are casually arranged in mineral water bottles, although the water they stand in came from the tap. There is something appropriate about them here, something recognisable from the photographs in front of me – the beautiful found within the make-piece and sustained by the most ordinary.

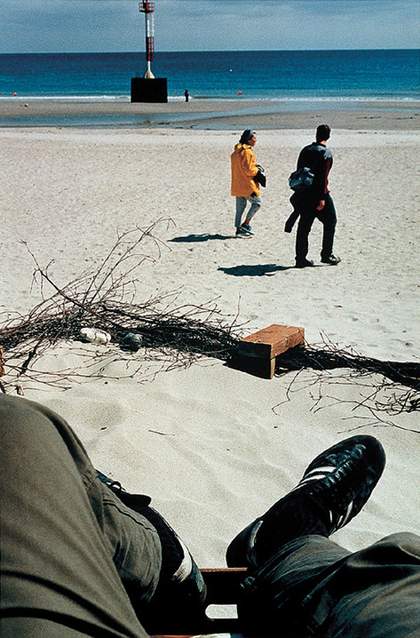

Wolfgang Tillmans

I don’t want to get over you (2000)

Tate

All photographs are of light, are made by light, although not all are about light. Not all of Tillmans’ photographs are about light either, or about it solely, but looking at a collection of them one gains a sense of its immense importance for him. It is not simply a technical necessity, or a formal device, but rather suggests a transformative process that is fundamental to photography, where the world around us seems to glow with meaning. Indeed, while looking at a photograph such as Shaker Rainbow 1998 one might ask whether light has meaning of itself. Here we see a beautiful white timber-clad house, caught in the thickened late afternoon haze. Its symmetrical façade is mottled by the shadows of trees that stretch into the frame on the right. Two overhead cables slice acutely through the picture while, arching from the top-left corner towards the bottom right, is a rainbow, its graceful curve ar rested by its meeting the gable of the building just behind. The sky is darker above the rainbow, as though the building is caught within a bubble of light.

The photograph was taken by Tillmans at a Shaker community in Sabbathday Lake, Maine, during an artist’s residency in 1998. It has the casual beauty of much of his work – indeed, beauty is something that does not seem to trouble him and consequently he has little trouble finding it – and might in some way be seen as emblematic of his relationship to the world, the miracle in the backyard, the everyday sublime. Tillmans has photographed the Shaker community several times now, returning to them as he has with other forms of community. Indeed, it is a community that – for all their differences – shares a great deal with those whom we might more readily associate Tillmans with, the groups of musicians and clubbers who come together in New York, London or Berlin. As Dan Graham relates in his classic video work, Rock my Religion 1984–5, the Shakers were founded by Ann Lee, an illiterate blacksmith’s daughter from Manchester, following a revelation that she had experienced in a trance ‘produced by the rhythmic recitation of biblical phrases’. Believing herself to be the female incarnation of God – Christ having been the male incarnation – she decided to create a utopian commune in America, leaving for the country in 1774. Here, the familiar nuclear family was replaced by one of co-equal Brothers and Sisters as the ‘Bible showed heterosexual marriage to be the unnatural result of Adam’s sin’. Each Sunday, the Shakers would meet to perform the Circle Dance, in which lines of men and women would form four concentric, moving circles. They marched, chanting, stomping their feet, shaking their bodies, clapping, jumping. Some removed their clothes. They would reel as a group together, each individual freed from their own sin within a form of collective redemption.

Although the Shaker movement is close to disappearing, its rituals continue within our contemporary societies, albeit in new forms Just as within the groups of chanting Shakers the saved would ‘reel and rock’ so, more than a century and a half later, the crowd would lose itself in ‘rock ‘n’ roll’, a form of self-empowerment generated by the individual’s subsumption within a group. This is obviously of great interest for Tillmans; not simply the representation of shared experience, important though this is, but the forms of individual transcendence that only become possible through the experience of ecstasy.

‘It can be spiritual,’ he explains. ‘That’s one of the strongest points of it: this idea of melting into one. Paradise is maybe when you dissolve your ego – a loss of self, being in a bundle of other bodies. It’s really the most regressive state you can be in on Earth. The other way to it is sex. Neither of the two is ideal as a permanent model for living. Clubbing and sex have great potential to go stale and become boring and repetitive.’

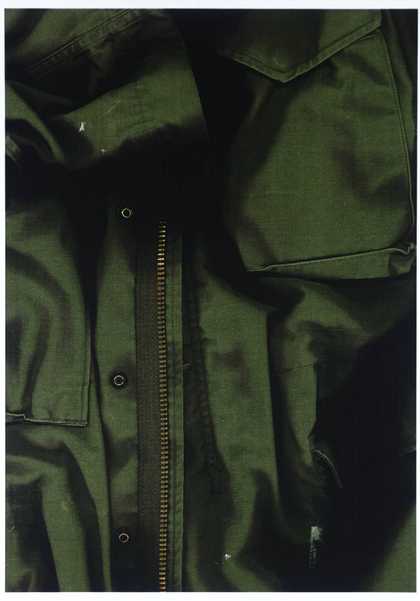

Wolfgang Tillmans

Faltenwurf (Cubitt Edition) (2000)

Tate

One sees throughout Tillmans’ work a longing that moves between engagement and retreat, a fascination for the crowd and all that comes from a shared experience, the ‘sensuous community’, but also those things which reveal themselves only when we find ourselves alone. These are the moments of reflection upon what has come before, an attempt, perhaps, to re-establish the sense of self that had previously been dissolved.

During the summer of 1997, the late American filmmaker Stan Brakhage bought a Bolex camera to replace the one he had worn out. It was not long after this that, passing Boulder Creek near his home in Colorado, he decided to test out the camera and, attaching some extension tubes he had been carrying since his father had bought him his first camera over 30 years previously, he began to film the stream. He did not film the surface of the water, however, but rather below it, that which bubbled underneath, not immediately apparent but important and real nonetheless. He had just discovered that he may have developed bladder cancer. The film which followed, Commingled Containers, featuring these underwater shots with sequences of blue-painted celluloid, was completed between his learning that the growth was cancerous and the removal of the bladder and subsequent chemotherapy treatment. The critic Scott MacDonald has written of Brakhage’s film: ‘The imagery of the bubbles is both ineffably beautiful and suggestive of the spiritual dimension of human life that lies just under the surface of everyday experience.’ One might say much the same about Tillmans’ work. Coincidentally, 1997 was marked by illness for Tillmans also. The day after the opening of his solo exhibition at Chisenhale Gallery in London, entitled I didn’t inhale, his partner, the artist Jochen Klein, fell ill with Aids-related pneumonia and did not recover. He died a month later. These events are, of course, unrelated, but they do share that sense of tragedy that trickles and stains the everyday.

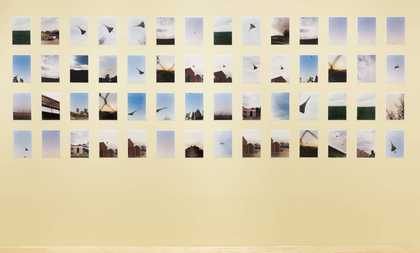

Wolfgang Tillmans

Concorde Grid (1997)

Tate

Perhaps it is this spiritual dimension lying just beneath the surface which brings together the many diverse elements of Tillmans’ work, and which can be seen in his most recent pieces, such as Icestorm 2001, which contain abstract shapes floating within a representational landscape. In another recent work, Quarry II 2001, a faint red trickle seems to run down in front of trees that stand before the rock face, a distinct artistic intervention upon an otherwise realistic scene. Yet, as the artist pointed out, one does not interpret the light green forms at the top of the picture abstractly, but rather as leaves which have fallen out of focus. In this context, perhaps we might see Shaker Rainbow as a precursor to these later works, where dramatic optical effects transform their surroundings, although in ways that might not be so easily understood. Light has a meaning here, certainly, as its absence does elsewhere in numerous photographs taken during a solar eclipse. It suggests a way of looking at the world, a way of looking that Tillmans has developed with remarkable sensitivity, and an awareness that the most powerful abstractions – life, death, love, fear, despair and happiness – are the most real of all, and can only be found within our own everyday.