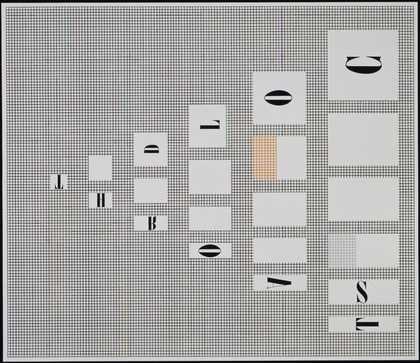

I am Richard Wright. I am a painter, and I have been asked by the Tate and the Contemporary Art Society to select from the Tate’s collection a small display of works which has as its starting point a work which has been donated to the Tate by the Contemporary Art Society. The display itself was intended to sort of mark the 100th anniversary of the Contemporary Art Society, which was founded in 1909. The title of the display is The Sleeping Congregation, and the title is taken from this etching by William Hogarth, which was made in 1762, and it’s quite a simple satire in the centre of which is a preacher giving a sermon. At the side here we see the congregation, who are all asleep. The preacher is just looking sideways at this lady’s cleavage, who is also asleep. The satire, the message, if you like, of the work is a kind of critique or criticism, not so much of the audience for not paying attention or for being lazy, as it is perhaps a criticism of the boring nature or the sort of lack of fervour in the message. And I think that for me this work resonates in some ways with some, perhaps emptiness, that I found in some contemporary art, especially in the way that it’s spoken about. We speak about contemporary art as something that is sort of just not getting through, that is somehow boring, that perhaps its ideas may be sort of high-minded or distant from people’s lives. You know, much of it might make us go to sleep, and of course what I’ve put together here is all selected – some of these things in themselves may seem sort of ephemeral, but I think what they have in common is an intention to draw you into a kind of attention, to lead you into a way of thinking or lead you into a way of believing. Part of my thinking in putting the display together was to try to create a setting that would perhaps slow down the engagement with the various things that are in the show, and to make the entire situation with which you engage, you know, as important as the figures themselves. And a second aspect of this, if you like, is the use of this vitrine, which in a way is a little bit like a model for the exhibition itself. In the case of this work by John Latham, which is called Five Sisters Bing, is a kind of model for something else. It’s a landscape, and so I’ve set it in this situation which I’ve tried to imagine as a bigger landscape. I’m quite interested in the idea that many of the pieces are intended to lead you into a different world. They are almost like a tool to open a box or a door. This work by Marcel Duchamp, this is called Why not Sneeze, and it has this, what appears initially to be slightly obscure mechanism by which the title of the work is really only accessible by the use of a mirror underneath the piece, and it’s a combination of elements which seem not to belong to each other, but they create a kind of enchantment. Their proximity creates a kind of enchantment. This work by Ed Ruscha from the 1990s is just a very simple painting of a circle on a book. It’s a vowel, the letter O, obviously, which is just a sound in itself, and part of my thinking in including the work was actually because it would draw in certain architectural elements which are outside the works. For example, here there is a speaker on the ceiling which is nearly the same size as the O, and there is another one at the other end here, and part of my thinking, actually, in the placement of the works, was to try and introduce the idea that the work doesn’t end – it doesn’t end with the boundaries, the border, the frame of the work, that actually that is just the beginning of the experience of the work. And I tried to do that with several pieces in the show, where I’ve tried to get the work to almost include something that is outside it. And I think the reason for that, or the thinking behind that, is just that you know, that perhaps when you walk out of the exhibition, that kind of thinking might continue, that you might also perhaps be able to see other things as being part of this, as well.