Nalini Malani

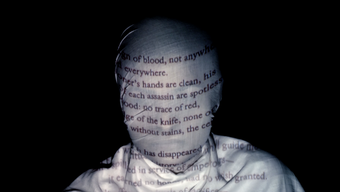

In Search of Vanished Blood (2012–20)

Tate

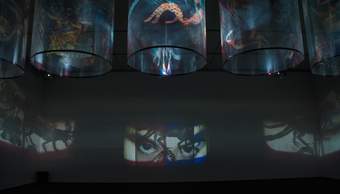

In Search of Vanished Blood 2012–20. Photo © Tate (Matt Greenwood)

‘People come up to me and say “your work is political”,’ says the artist Nalini Malani, ‘I reply, “the water you drink is political”.’

Nalini Malani

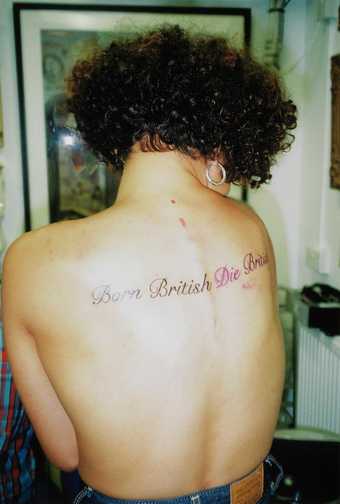

Multimedia artist Nalini Malani was born in Karachi in 1946, one year before Partition. At the time of Independence from the British Empire, two countries were formed: India and Pakistan, split across religious lines. This event is known as Partition, and it forced people from across the subcontinent to leave their homes and start new lives in unfamiliar places. Malani’s family had to move from Karachi to Calcutta, from what is now Pakistan to India, and her art practice has been shaped by this early journey. Malani challenges conventional understandings of nation-state and identity. She does this by revisiting stories and iconographies, like those of the Hindu and Greek mythologies, and the great works of South Asian film, literature, poetry and music. She paints, makes films, and builds installations that fill up large spaces with many connected elements. These installations are theatrical and immersive. One example of this is In Search of Vanished Blood, made in 2012, commissioned by dOCUMENTA(13). The artwork includes theatrical projections and shadow-play shown across gallery walls and floors.

A closer look at In Search of Vanished Blood

In Search of Vanished Blood fills up an entire room. At its centre are five rotating cylinders, around which are slowly moving, fragmented silhouettes of animals and people. They play in a loop, surrounding you as you enter the space. The scene is playful and mysterious, and the moving images are produced by overlapping films and shadows. This is Malani’s artistic language. She mixes animated and inanimate mediums – like film and painting – and still and moving images. She calls it ‘video/shadow play’.

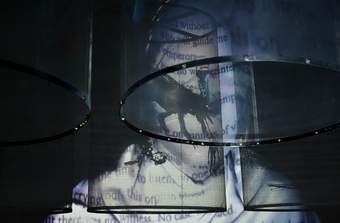

The video/shadow play in this work is created by six synchronised films that are projected into cylinders. These are made of a polyester plastic known as Mylar. Mylar, which has special reflective properties can withstand extreme temperatures, and it can even conduct electromagnetic energy. By painting on this material, Malani skilfully blends its many characteristics into her work. As a result, her paintings take on a curious glow as we stand under the slow-moving cylinders.

Malani has painted scenes onto these cylinders using an improvised Byzantine technique known as ‘reverse painting’. In the mid-nineteenth century, it was a style of painting popular with the Indian court painters, who used it to depict ornamented scenes from mythology, as well as portraits of rulers and landscapes . First, artists would place clear sheets of glass onto original drawings and copy them. Next they would fill them with metallic foil, sequins and beads. Then they would delicately shade in the coloured paint with tempera paint. Lastly, they would flip the panels over and view the paintings through the glass. Malani repeats this process on the Mylar, which is transparent like glass, but thinner, and more flexible, so she is also able to fold the sheets into cylinders. She uses acrylic to paint on the Mylar. The cylinders of In Search of Vanished Blood rotate four times every minute, and the projections are pointed toward them, filtering one set of images through another.

The title of the work is from the Urdu poem Lahu ka Surag penned by the Pakistani revolutionary poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz. The English phrase ‘In search of vanished blood’ is found in the translation of the poem by the Kashmiri-American poet, Agha Shahid Ali. ‘I’ve searched everywhere,’ goes the poem, ‘there’s no sign of blood, not anywhere.’ No marks on the sleeve, it goes on, no drops on the edge of the dagger. In Malani’s installation, the poem is projected on a fully veiled woman who seems to be tortured by waterboarding. Stop-motion animations flash on the Mylar, and onto the walls: scenes of Spanish painter Francisco Goya’s prints from The Disasters of War (1810-20) series; and more contemporary depictions, of Taliban fighters in Afghanistan, and Maoist rebels in north India. At the very end, you see American Sign Language (ASL) spelling democracy very rapidly and urgently.

Malani and South Asian literature

Nalini Malani In Search of Vanished Blood 2012 (detail) Courtesy the artist © Nalini Malani

Nalini Malani’s work is incredibly literary. As with her interest in the poetry of Faiz Ahmed Faiz, she has a particular focus on the writers from South Asia who chronicled the immediate years after independence. These writers were trying to articulate and give language to complex subjects: like the displacement from home, or the sudden onset of violent clashes between communities. In Toba Tek Singh, a short story by Saadat Hussain Manto, a group of Hindu and Sikh patients are being moved from Pakistan to India. Strange events occur along their journey: patients climb trees and stay up there, and some sit down on thin strips of land not yet mapped by cartographers. In The Dog of Tithwal, a friendly dog darts between army camps in India and Pakistan, but neither side can figure out where the animal belongs. The dog, of course, remains oblivious to borders. Writers like Manto turn our attention to the absurdity of national borders.

Another one of these writers is the novelist Mahasveta Devi, and Malani references her story Draupadi in In Search of Vanished Blood. In it, an indigenous woman by the name of Dopdi (or Draupadi) is kidnapped by an army officer, Senanayak, who degrades her. The feminist scholar and postcolonial theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak translated this story from Bengali to English, because, she wrote, ‘in Senanayak I find the closest approximation of the First-World scholar in search of the Third-World.’ Spivak is critical of the practice of turning the stories of women from countries like India and Pakistan, the postcolonial countries, into abstract concepts, or purely academic concerns. She says, ‘We grieve for our Third-World sisters; we grieve and rejoice that they must lose themselves and become as much like us as possible to be “free”.’

Malani, like Spivak, casts an analytical eye on how women have been represented in the great canons of history, especially in episodes when their voices have been taken away from them. Her references range from South Asia to Ancient Greece. One of the main characters in In Search of Vanished Blood is Cassandra, from Aeschylus’s tragedy of Agamemnon; she is a prophetess, the daughter of the last king of Troy. At the beginning of the soundscape that accompanies Malani’s installation, we hear Cassandra, who tells us about the state of the world, and chronicles moments of violence, especially those toward women, while a background chorus reacts to her speech.

the myth of Cassandra

Cassandra is the daughter of Priam, who was the last king of Troy; she was the most beautiful of his daughters, her mother’s name was Hecuba. The god Apollo fell in love with Cassandra, who said he would bestow her with the gift of prophecy if she fulfilled his desires. She accepted his gift but refused to meet Apollo’s demands, they did not suit her. In turn, he cursed her: Cassandra would still have the power to see the future, but no one would believe her.

Nalini Malani not only draws from this story for In Search of Vanished Blood but also from a contemporary retelling of it: Cassandra by East German writer Christa Wolf. In Wolf’s writing Cassandra is reflecting on her life as it reaches its end, she is awaiting her death; she is being held prisoner by the Greek army during the fall of Troy. In the opening passages of the book Wolf’s own voice intermingles with Cassandra’s: the two are unified in their solitary feeling under oppressive regimes – Wolf in post-World War II East Germany; Cassandra in the guardhouses of a fallen Troy – both are visionary voices whose fortunes of the world were disregarded, both are women, storytellers, locked in a struggle to be heard.

In Malani’s narrative-building, Draupadi, too, from Devi’s story, is brought together with these women. Draupadi’s story is not dissimilar to theirs, hers is a kidnapping that occurs against the backdrop of armed resistance in the jungles of West Bengal, she finds herself caught between conflicting aspirations and claims. In Search for Vanished Blood brings together these women so that their voices may finally be audible, reverberating through the space that we enter, where we step into the moving shadows and their layered prophecies.

Malani’s art-making practice

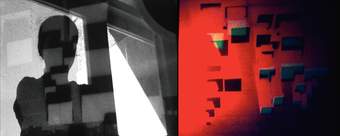

Nalini Malani attended art school in Mumbai, the J. J. School of Arts in the southern end of the city. During her time as a student, she received traditional schooling in painting and portraiture. Her practice took a significant turn when she was first introduced to film, making her one of the pioneering female South Asian artists to fully embrace the medium. In 1969 Malani was invited to be a part of the Vision Exchange Workshop (VIEW) led by renowned painter Akbar Padamsee; she was one of only two women, along with the artist Nasreen Mohamedi, and the group’s youngest member. Padamsee had used a Nehru Fellowship grant together with his personal funds to create the initiative, a valuable and much-needed artistic platform for exploring technology. Padamsee gathered a group of painters, printmakers, animators, sculptors, cinematographers, and even a psychoanalyst, in his Bombay apartment. Malani was a fast learner and worked with remarkable agility and speed, in just six months she made three films. For one of them, entitled Dreamhouses, she built a city from black cardboard and photographed it from various angles. She processed the negatives of these in grey and black tones and reshot them on 8mm film.

Photo of Nalini Malani in City of Desires 1992, Courtesy the artist © Nalani Malani

Once, early in her practice, a friend took Malani to see rare Jaipur frescoes in Nathdwara in Udaipur, a city full of lakes in Rajasthan, India. Malani found a fresco on the facade of a gymnasium, which was being used as a kitchen by the staff of a nearby temple; it was a rare placement of an otherwise precious decorative item reserved for the interiors of a building. Due to years of neglect, the frescoes were barely visibly beneath layers of soot and grime. The priests would not allow for the frescoes to be cleaned – on assumptions that this would compromise their religious integrity. Malani, unable to forget this careless treatment of an ancient history – decided to process it through making. Soon after, she held a show at Gallery Chemould in the Jehangir Art Gallery Mumbai, in which she covered the entirety of the space with wall murals, which she describes as an act of ‘mourning’ the lost frescoes. She made elaborate drawings of the Lohar Chawl area where her studio was, and the wholesale markets of the neo-Gothic Crawford market. She covered the floor with red oxide powder so that every visitor left the space with blood-red soles – staining the marble steps of the Gallery’s exit. The wall drawings (City of Desires) were erased after this. Malani’s drawings were gone forever. But this is part of her work, she calls ‘Erasure Paintings’. South Asia cultural traditions have long histories of negotiating impermanence, as with every erasure is the opportunity for a renewal.

why myths

‘I use myth because the artist’s endeavour is always to connect with the people who come to see one’s work,’ says Nalini Malani, ‘and mythologies are link languages. They have come to us like universal truths.’

The artist has a particular interest in mythology because of how myths can hold truths, idioms, and morals through simple storytelling devices that are recognisable across cultural references. Myths are powerful things: they can build political ideologies around them too, and India today is a place where myths are being revised, contested, and even used to turn communities against each other. This is a continuation of the history because of which Malani herself was displaced as an infant – the forced conflict between Hindus and Muslims in India.

‘For me, history is not episodic,’ Malani says, ‘I am not interested in the past, what I am interested in is how it activates itself in the present moment.

About Skye Arundhati Thomas

Skye Arundhati Thomas is a writer, editor and curator currently based in Paris, in residency at the Beaux Arts de Paris and the Pernod Ricard Foundation. Their second book, Pleasure Gardens: Blackouts and the Logic of Crisis in Kashmir is out in May 2024 with MACK Books.

Research supported by Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational in partnership with Hyundai Motor