Nasreen at her studio in Bombay at the Bhulabhai Desai Institute Dated 2 Nov 1960

Photograph 4.2 x 6.2 in

Courtesy: Sikander and Hydari Collection

I first came across Nasreen Mohamedi’s drawings in Nasreen in Retrospect, a commemorative book her brother Altaf and her family had published in the mid-1990s, after her death. The pristine black-and-white line drawings took me by surprise. They seemed familiar, constructed from within the language of modernism, but with a subtly altered vocabulary; a recognisable tongue in a strange dialect. But now, having worked with her drawings for a decade and a half, it has become clear to me that the lines in her drawings intersected at a particular moment, made possible by a unique set of circumstances – personal, cultural, social and historical.

Nasreen was born in Karachi (now in Pakistan) in 1937, but moved with her family to Bombay after her mother died when she was seven years old. In 1954, at the age of seventeen, she left for the UK to study at Saint Martin’s School of Art in London. Travel was a big part of her life: she visited the Arab Emirates, where her father and brothers had business interests; France, on a scholarship from the French Government; Bombay, where she set up her first studio; and Delhi, where she stayed for two years before making her final move to Baroda in 1972.

Nasreen Mohamedi, Untitled c1970s

Ink on paper, 490 x 490mm

© Estate of Nasreen Mohamedi, courtesy Gopai Mirchandani

Nasreen’s development as an artist was informed by several factors: her exposure to a diverse geography, the work she encountered in the West (for example, the lyrical abstraction of the post-Second World War artist Georges Mathieu and the ‘all over’ Indian ink drawings of Henri Michaux) and the abstract tendencies in Indian art that she came into contact with through her friends, the artists VS Gaitonde and SH Raza. Her early works from the 1960s had close correspondences with Gaitonde’s almost monochrome canvases. However, it was after she moved to Baroda to teach in the fine art department at Maharaja Sayajirao University that she began to produce what have come to be seen as her classic works: small-scale line drawings, painstakingly composed using pen and ink.

At the time, it was one of the leading visual art departments in India, with artists such as KG Subramanyan, Gulam Mohammed Sheikh and Nilima Sheikh, and prided itself on a figurative painting style that fused local narratives with indigenous traditions. But Nasreen remained resolutely committed to abstraction.

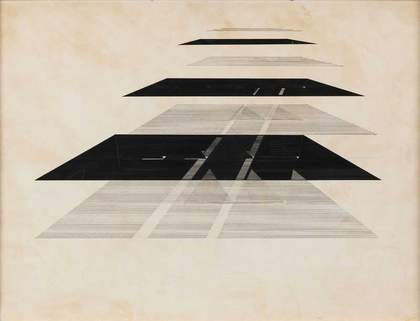

Nasreen Mohamedi, Untitled c1970s

Ink on paper, 510 x 710mm

© courtesy Chatterjee & Lal

It is difficult to construct a precise chronology of her practice, as she rarely signed or dated her work, but by the time she moved to Baroda her work had already lost all traces of figuration. Her earlier watercolours, ink drawings on paper, oil on canvas, collage and lithographs that were lyrical and semi-abstract (often suggesting trees and landscapes) had made way for a more austere phase. In the 1970s Nasreen stopped painting on canvas or using paint wash altogether, and started meticulously constructing her compositions of lines on square sheets of paper using the ‘grid’ as a template.

The grid offered the possibility of what she called ‘pure intellect that has to be separate from emotion’. But her use of the grid as a compositional device was crucially different from that of other modernist artists from the West.

While it seemed like Nasreen was embarking on an exercise of ‘symmetry’ in her grid drawings, almost everything that followed was asymmetrical. The density of the lines varied, depending on the ‘load’ of the ink she carried in her pen; her horizontal lines almost never had corresponding verticals, but instead had ‘fragile, stringy lines that looped into the horizontals, resulting in a ‘precarious joinery’ rather than a ‘pristine grid’. (Geeta Kapur, With Frugal Means: Nasreen Mohamedi, 2009.)

Like women artists from other parts of the world, such as Agnes Martin and Bela Kolárová, Nasreen subverted the modernist grid and infused the lines with a sense of rhythm and variation influenced by her own personal experiences - her studies in Europe, her knowledge of Zen Buddhism and Taoism, Indian music, Arabic calligraphy and Islamic architecture, the desert landscapes of the Gulf and the seascapes of Kihim.

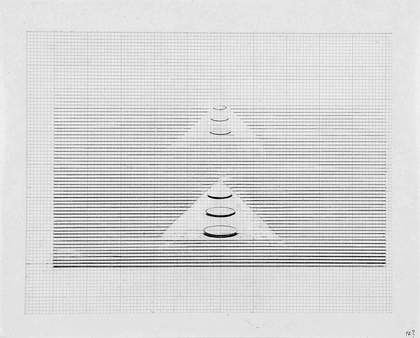

In the early 1980s her work with the grid gave way to dynamic configurations of geometric forms - diagonals and chevrons - on rectangular sheets of paper. And in the last two years of her life she introduced circular forms - arcs, half circles, ellipses and discs - that floated freely within an empty space.

Nasreen Mohamedi, Untitled c1970s

Photographic print on paper, 280 x 343mm

© courtesy Chatterkee & Lal

In addition to her drawings, Nasreen also produced extraordinary black-and-white photographs throughout her life. Although she wasn’t trained formally, she adapted the medium of photography as a tool for the spatial investigation of light.

There is little documentation about Nasreen or her practice, and it is only from accounts of her peers, friends, students and family that one is able to build a picture of her. For instance, artist Jeram Patel, with whom she shared a similar visual aesthetic, remembers her sitting cross-legged on the floor of her stark, monk-like studio, listening to classical Indian music, working late into the night before her tilted drawing board. Her life and art were very closely linked, and this is attested to by the beautifully crafted diaries that she kept almost all her life. Often poetic and intimate, they tell of the inspiration she draws from the perfection of nature; of the books she is reading - Camus, Rilke, Lorca, Klee, Kandinsky - and of moments of elation and despair. Her art, it seemed, was a filter through which she balanced her ‘inner experience and outer reality’.

Nasreen Mohamedi, Untitled c1980s

Pencil on graph paper, 200 x 270mm

© Estate of Nasreen Mohamedi, Courtesy: Collection of Gayatri and Priyam Jhaveri, Mumbai, India.

Nasreen’s was a singular practice. Though well-respected as an artist during her lifetime, she was little known internationally because the globalisation of Indian art began only in the late 1990s. From someone whose work was rarely seen outside the country twenty years ago, Nasreen Mohamedi has become an artist whose drawings have been included in some of the most important exhibitions in the world today.