In 2008 Tate Modern presented an exhibition of the late works of Mark Rothko. The show’s curator, Achim Borchardrt-Hume, took us on a tour featuring the iconic Seagram Murals, Black-Form paintings, and the Black on Grey paintings – the last series made before Rothko’s death in 1970.

Find out how much importance Rothko placed on the way his work was displayed, and why these mysterious rectangles of layered pigment hold such enduring appeal.

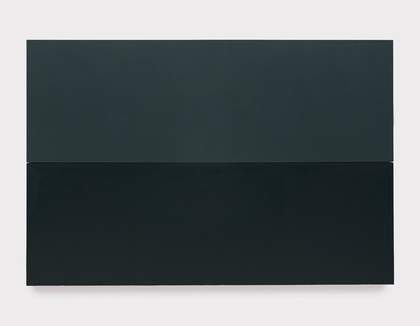

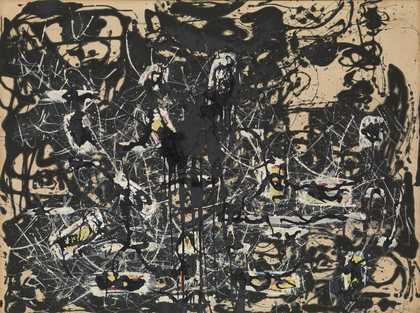

Rothko was commissioned to do these paintings for one of the most expensive restaurants in New York. He took the commission on with great enthusiasm. He went to rent a new studio down on the Bowery, where he simulated the dimensions of the dining room, and although the restaurant would only have offered space for seven murals, in the end he executed 30 paintings. So what we have done in the exhibition is, we have take the Seagram murals as the starting point for his exploration of working in series, as this marked a turning point in his career. Rothko was always very concerned with how his work would be viewed, with actual conditions. And I think what really interested him was in some way to transport the conditions in which he was working in the studio into a gallery space, rather than seeing them as this very enveloping environment as you usually see them in the Rothko Room at Tate. You now see them, I think, in a far more architectural way. They seem to be much more engaged. They appear like portholes or windows. They seem to almost break through the wall. The other thing which I thought was very curious when we brought so many paintings together, and suddenly they have a completely different pace and rhythm, and rather than just seeming very calm and contemplative, they are moving much faster and are much tougher. They are known as Black Form paintings. They were first series that Rothko himself identified as such by giving them numeric titles in consecutive order from one to eight, though curiously there are nine paintings with number five appearing twice. And these little inconsistencies are quite typical for Rothko, that there is something very precise, but also something, a space being left open. What really stands out is that Rothko’s engagement with black in these paintings continues to remain far more painterly. If one looks at his canvases, you can see after a little moment, as your eye gets used to the palate really, that they are far from being simply black. They are very dark plums and dark violets, and they often have a bluish blackish field. There is always a little colour hue in there. And I think one of the things that makes this extraordinary quality of Rothko’s canvases is that they are almost like blank cinema screens. You almost have the sense you, as the viewer, now begin to project onto the canvas. So there is a space for response. It’s also very much about duration. It is how long can you look? How long is comfortable? How long is long enough? And duration was very much a concern at the time, where Rothko beforehand had mostly used these flourishing colour fields on a ground, and even still in the Seagram murals, where the relationship between figure and ground in a way had been reversed; it was the frame that had been floating, there was still the sense of there is something behind and something in front, and this very airy connection. These work completely differently. You’ve got gesture, you’ve got brush work, but everything is reduced, really, to its most quintessential characteristics, and then condensed into the seemingly simple, but actually quite complex, compositional scheme. In 1969, Rothko embarked on his final series of paintings on canvas. Rothko’s paintings beforehand had always been projecting from the wall, or so it felt, into the viewer’s face, thereby inviting you to sink almost into the canvas and into the colour field. There is always a lot of, one is tempted to say, action or drama really happening around where these two fields meet. Sometimes you can see the grey goes over the black, or the black comes back over the grey, and it’s almost as though these two fields fold around one another. There is this tendency to read Rothko’s late works in terms of psychobiography; to talk about where he was at in his life, was he depressed is a common question. And I would propose to look at it in an entirely different way. He decided to embark on this very risk-taking venture of conceiving a whole new body of work, a different type of series that questioned everything he had done beforehand; that seemed to push the question of what could paintings still do by that point in time. So I see it much more as a reassertion of a painter at the height of his powers, rather than of a man in decline.