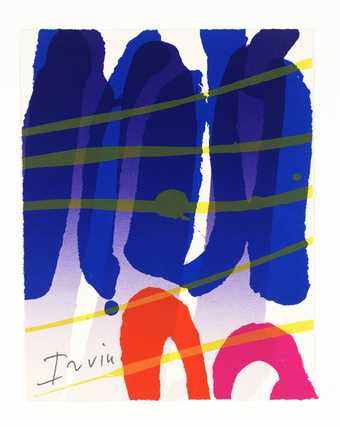

I’m Albert Irvin. Everybody calls me Bert. And I’m here in the Tate Store to talk about my paintings, which I’m delighted to see again. I haven’t seen them since they were last shown at the Tate. And I’m quite proud of them – they look a handsome trio. I used to do figurative paintings with subject matter and so on. I wanted something more direct; I wanted to have immediacy of contact with the spectator, like music does. I saw the American exhibition at the Tate – Pollock, de Kooning, Kline and Rothko and all, and Barnett Newman. It was really like a great bomb bursting. And I gradually came to feel that I could make paintings about the human condition without having to put bits of human beings in them. Well, the Flodden Road – I was teaching at Goldsmith’s at the time, and this was a road that I used to go down. They are abstract paintings, whatever that is, and I felt that they were informed by my movement through the world, my world, and urban world, and the streets are a kind of symbol for this. You’ve just got the colour and the structure, the bones that hold it. And then other things to compliment it, to kick it into action, like the green and the blue. These aren’t expressive marks at all; they are pushed into place, and the material itself does the painting. You’ve kind of offered the thing out there, and it’s done it itself, in a way. And this is one of the things that I reacted against later. I felt I wanted to make an autographic mark. Nineteen eighty two was quite an exciting year for me, so you got all the kind of buoyancy that I was feeling. I had wanted to be able to feel that the marks I was making were actually expressive, were autographic, like a diary – where were you at half past four – I was up there, and what about a quarter past six, I was down here, so to speak. This was in nineteen ninety five. The title, of course, is obviously A Love for Paris.