Various Voices: Dynamic. Can-do. Puckish. Beauty, playfulness and influential.

Francis Hardy (Assistant Curator): Helen was born in Croydon in 1953. Her father was British, and her mother was Greek. They'd met when he was serving in Greece during the Second World War.

Helen Chadwick: “They wrote letters to one another, and then at the end of the war, he sent for her to be married.”

Francis Hardy (Assistant Curator): Initially, she'd wanted to be an archaeologist and had hoped to draw the archaeological finds, but she decided to go to art school instead.

Ceri Lewis (Senior Curator): I'm looking here at an image which comes from a very early work of Helen’s, which she made while she was still a student. We are seeing her dressed within a framework of a kitchen sink and this is one of a series. There was an oven, a washing machine—where the central element of the washing machine effectively alluded to a sort of pregnant belly—or an oven, where each of the hob rings became almost breastplates.

She was questioning the role that women were being asked to take, the roles that seem appropriately feminine. And I think here it really captures the sharp, sharp nature of her intellect.

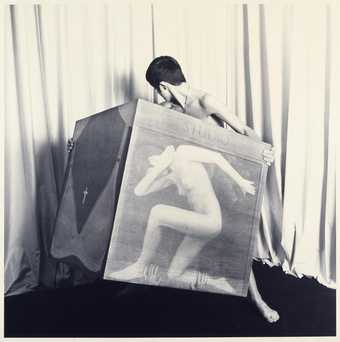

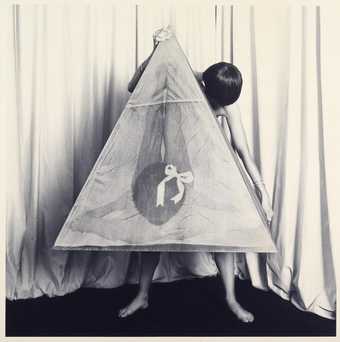

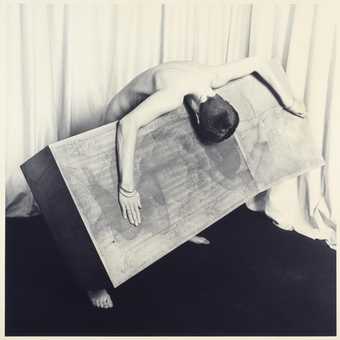

This is really Helen at the height of her work, which is about performance and exploring that nature of live action. We see an image of Helen herself, and that's so key for her work that Helen features. Most of her later practice remains around that idea of selfhood and the mutability of self and the body.

Helen Chadwick: "I sort of felt more and more alienated from my own sense of self. So I thought, well, it's time to actually do something more for me, about me, just for my own sanity. And I thought, well, embarrassment a-go-go, let's do something autobiographical, and that's how Ego Geometria Sum began."

Errin Hussey (Archivist): Ahh Brilliant. This is Helen's work Labours, which became part of Ego Geometria Sum. And Ego Geometria Sum started with Helen wanting to print images of significance to her onto plywood and then making them into sculptures of various sizes and shapes that represent what were containers for her body throughout her life up to that point.

It started with the incubator, representing birth, and then here we have the pram. She made Ego Geometria Sum when she was turning 30. Each individual sculpture all ten go up in scale. So the older she gets and the older she’s representing with the sculptures, they get bigger and bigger.

And you can tell from her annotations how much she was researching into each individual work but also how that came back to her personal life. She wanted to reflect on her past and all the influences on her during that time, and what it means to be herself in that moment.

Helen Chadwick: "At the time, I thought, oh, the photographic community are going to love this because it was so difficult to photosensitize plywood and print quite large photographs directly into the wood. It was like being a kind of Victorian, mixing up chemicals in bottles and using hairdryers in the pitch darkness, exposing things, having no idea how they would turn out."

Ceri Lewis (Senior Curator): In the 1980s, she was starting to receive real recognition. I think perhaps a really important work for that is the ICA in 1986, Of Mutability, for which she received a nominated for the Turner Prize in 1987. One of the first women to be nominated for the Turner Prize.

Andrea Schlieker (Director of Exhibitions & Displays): Oh, yes. I met Helen Chadwick in the eighties when I was a curator at the ICA here in London. We had invited her to do a show, so I curated that show. It was called Of Mutability, and Helen really stood out as a major practitioner in her field. But she was a real powerhouse. She was full of energy, mischief, humour. An incredible dynamo.

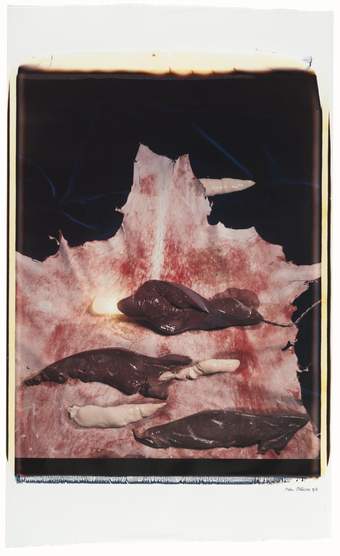

This is a photograph of Carcass, which was a glass column—an empty glass column—which Helen filled with organic waste. But it had to be filled all the time, because after a while it began to bubble, it began to ferment. It was like a live thing in the gallery. You could hear the bubbling and the crackling inside this column. When you looked at it, it was almost like a beautiful abstract painting with all, with layers of different colours. It was stunning to watch. And then, after a few weeks, there was an explosion, and the whole thing disintegrated. And all its oozing, smelling, fetid stuff spilled across the room.

Helen Chadwick: "Yeah, I mean, I imagined it would be like a sort of emblem of death and mortality, but what I hadn't anticipated was the fact that there would be this fermentation process. So ironically, it became more a metaphor for life."

Louisa Buck (Writer & Broadcaster): I certainly knew about Helen way before I met her. She was very much in the art world with this short, helmet-like black bob of hair. This great smile, these amazing clothes. She was this very animated, big presence within the art world. And we became very close friends. We just kind of became friends. I don't remember a particular moment, but she was just absolutely in my life.

Ahh, so there’s Helen, surrounded by twelve versions of herself in The Oval Court, which was part of her great Of Mutability show at the ICA. Helen's use of materials was definitely provocative. The most provocative thing she probably did at the beginning was use her own naked body.

There she was adorned, beribboned, naked. Floating in this kind of blue background with photocopies of animals, a lamb, a goose, maggots, flowers. I mean all of these things and looking absolutely amazing.

And I think a lot of people found that very problematic, particularly within the hardcore feminist movement at the time. They felt she was putting herself on display, she was objectifying herself. But it wasn't about an autobiographical account. It was about Helen being every woman.

Helen Chadwick: "Well, I was trying to open up a territory for desire, how to depict desire and physical sensation and pleasure. And given that one's experience of that is through the body, it seemed to me that the body was central to the project. And I thought, well, if I use something like a photocopier, it's just me pressing the button. It's much more intimate."

Louisa Buck (Writer & Broadcaster): Her work was about identity, being in the world. All these different kinds of experiences. So what better person to explore that than herself?

The notion of death and life, the interconnectedness of the two runs through almost everything Helen made. But it was also very much about Helen’s spirit. She was full of life, but actually she was surrounded by death.

Helen Chadwick: "They’re pure. Something that's permanent. Something that's beyond change."

Ceri Lewis (Senior Curator): In 1988, she decided to stop using her body and images of her body entirely. At that point, animal flesh, cells, other materials, visceral materials started to come into play.

Piss Flowers, her work of 1991, came from a residency she took at the Banff Art Centre in Canada. She had met David Notarius, who would become her husband. This was an opportunity for her and David to be able to work together on a residency.

David Notarius (Helen’s Partner): My first impression of Helen, was I just met this tiny woman who was looking for a screwdriver. She was just really, really sweet and funny. She had a way of making everything sound like fun or joyful or interesting. Never dull.

This is behind the Banff Art Centre, we're getting ready to do casting for one of the Piss Flowers. What we would do is make a mound of snow, pack it down with a shovel. We put a mould around it, push it down and take turns peeing inside of it before we cast it in plaster. It was very cold I remember that. Some people thought it was playful. Some were shocked. Some people couldn’t understand what we were doing.

She took risks where other artists wouldn't take risks, which opened the doors for other artists using other materials that you normally wouldn’t use. She basically taught a lot of people to think outside the box

Helen Chadwick: "Sometimes I look at them and I think, Gosh, they're amazing. They're truly fabulous in that you just can't really account for how they could be like that. I guess because they're not devised. They're the product of things that happen, chance things. And yet there's an incongruity between how they were made and now what they are, which is the sort of leap of the imagination, isn't it?"

Ceri Lewis (Senior Curator): It returns to her early roots of almost performative practice. Interestingly, you have this inversion of the typical male-female. Helen’s urine creates the long sort of penile forms, and David's pee is more dispersed and creates this sort of sensuous labial petal-like form. And it's her sort of playing with these taboos in a humorous, witty, concise, and wonderfully realised form.

Francis Hardy (Assistant Curator): So this is a beautiful photograph of Helen at the microscope whilst working on one of her final collections of work titled Unnatural Selection. In the nineties, she was invited to take up a residency at King's College Hospital in London in the Assisted Fertility Unit there.

Helen worked with the doctors and scientists in the clinic to really understand, from an artistic point of view, the IVF process. She was intrigued by the way in which the doctors would select the fertilised eggs that they wished to reinsert back into the mother. And what the doctors are looking for is to see whether these cells have clearly divided.

I think she was fascinated by the sort of aesthetics of this process, that the doctors were making a judgement based on what these cells looked like. And from these photographs that she took, she sought to incorporate them within sculptural works that took the form of a brooch, a necklace, and a ring, perhaps like Victorian mourning jewellery. So it links to the passage of life as well as the moment of creation, the whole biography of the person. What is both poignant and also quite tragic about Unnatural Selection as a body of work is that it's the last series that Helen completed before she tragically died when she was 42.

But even cut short as her career was, there's something about it that is so complete. That is so consistent in the arguments that she's making. There's no room left for chance. Nothing is unfinished or unsaid.

Director: When you think of Helen Chadwick, what three words spring to mind?

Louisa Buck (Writer & Broadcaster): Magnificent, mischievous, and utterly original. There's never been anyone like her, and there never will be.

In this film, we sit down with curators and those who knew the artist to explore Helen Chadwick's life, career, and the themes behind 6 key artworks. The film highlights her innovative use of personal experiences, body imagery, and unconventional materials. Interviews reveal her wit and influence, showing how her art evolved to tackle themes of identity and mortality.