Cornel Brudaşcu

Composition 1970

Museum of Art Cluj-Napoca, Romania

© Cornel Brudaşcu

Far from being purely an American art phenomenon, pop art spanned the globe. The1950s and 60s may have been a time of economic growth in America, but they were also decades of social upheaval and unrest around the world. Countries and societies were reeling from the fallout of the Second World War; conflict was raging in Vietnam; and the rise and rise of Communism was causing panic. Artists were uniquely placed to satirise and deride politicians, film stars – and even other artists, using humour, sex, and innovative techniques to provoke, parody and reflect.

Marcello Nitsche

I Want You 1966

Museu de Arte Moderna, São Paulo, Brasil

© Marcello Nitsche

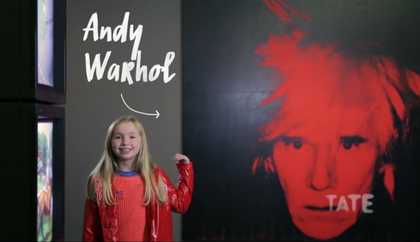

To the outside world, many of the artists in Tate's 2015 The EY Exhibition: The World Goes Pop existed on the peripheries of the movement. Andy Warhol made the news with headline grabbing quotes – and continues to be the poster boy for all things pop – but artists working across Europe, Latin America, the Middle East and Asia were hugely prolific. They proved the movement was not just American, British – or male. In the World Goes Pop, their significance was re-examined in an explosion of visual stimulation.

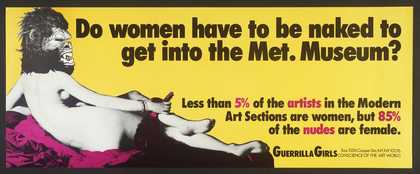

Body Politics

Instead of being a purely ‘decorative’ element within a composition, the female body emerged throughout the 60s and 70s as a legitimate tool of protest and empowerment. Artists created work that examined and questioned depictions of the female body in art and popular culture. The body was being reclaimed. No longer merely fetishised and glossy; uncomfortable questions were being asked of its role in visual culture and mass media.

Evelyne Axell

Valentine 1966

Private collection

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2015

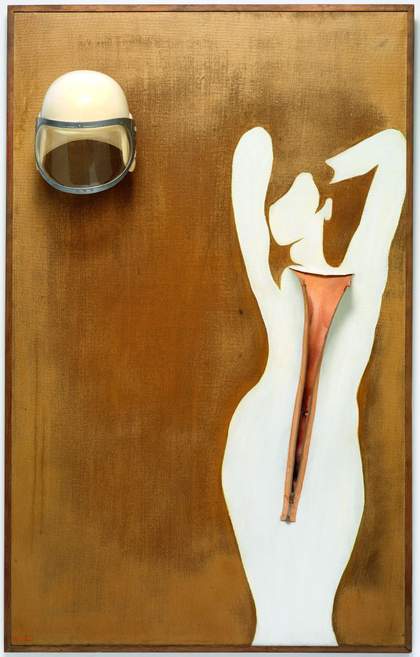

Artists such as Evelyne Axell (who for a time used the gender-ambiguous name Axell) decided that the body now stood for power, liberation and equality. Introduced to painting by family friend René Magritte, Axell’s 1966 work Valentine was produced as a homage to Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman (and civilian) to go in to space. By attaching a helmet and zip to the canvas, Axell invites the viewer to peek through the zipper at the flesh beneath. Acutely aware of the way women were seen in a male-dominated industry, her work frequently challenged perceptions of images of the female body and sexuality. Despite her achievement of space exploration, many only commented on Tereshkova’s physical appearance. To further highlight this absurdity, Axell staged a happening in which a model performed a reverse strip-tease. She started naked apart from an astronaut’s helmet, adding layers of clothing as the performance went on. Catalan artist Mari Chordà also explored anatomy in Coitus Pop 1968, by abstracting the sexual organs in a burst of enamelled colour on wood – graphic shapes that are unmistakably phallic.

Mari Chordà Coitus Pop 1968

© Mari Chordà

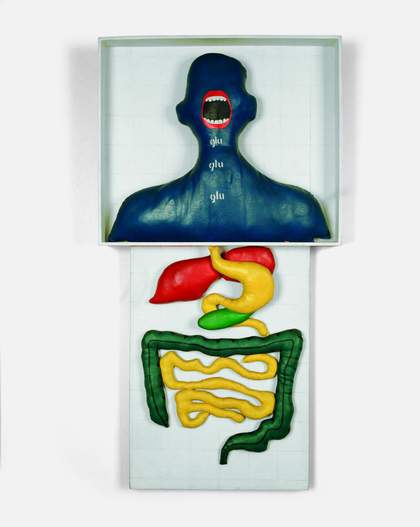

In Anna Maria Maiolino’s striking Glu Glu Glu 1966, a disembodied head sits above brightly coloured intestines. She is female, but anonymous. The body parts are recognisable, but disconnected from the whole. The work is beautifully constructed using quilted fabric. Although we think of this type of material as soft and homely, used in this way to make glossy internal organs it becomes repulsive, visceral and unsettling.

Anna Maria Maiolino Glu Glu Glu 1966

© Anna Maria Maiolino. Courtesy Gilberto Chateaubriand MAMRJ Collection

War and Peace

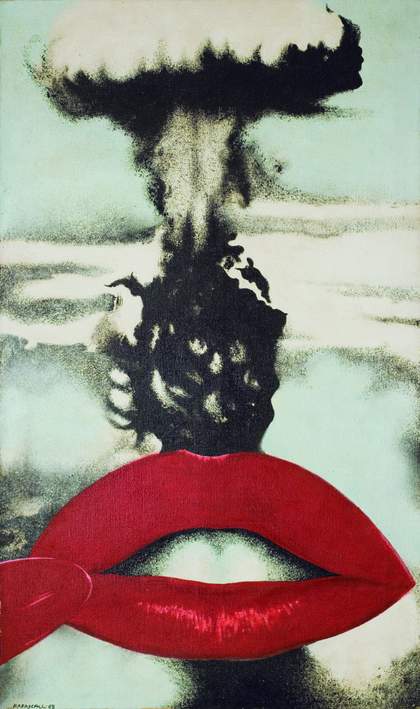

American pop art is known for being about consumer habits and new fashions. To many global artists however, the language of pop art was a vehicle to comment on political events and recent history. Nothing was off limits; Joan Rabascall’s Atomic Kiss was made as part protest, part warning sign reflecting the very real threat of an impending world war that terrified a generation. Rabascall describes his motivation for using found imagery:

What was important, I believe, was to get away from abstract art, which was very present in galleries, and do something that was corresponding to the time in which we were living

Joan Rabascall Atomic Kiss 1968

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2015. MACBA Collection

America’s influence on fashion, art, music, and technology around the world was a new kind of imperialism and was something that many of these global pop artists commented on. They depicted the American flag or President Kennedy – whose assassination in 1963 rocked the United States to the core, but also caused ripples that were felt globally. Often these motifs were adopted along with a fascination in the materials, processes and subject matters employed by Robert Rauschenberg, Tom Wesselmann and other American pop artists. A truly international society opened up with cheaper air travel and imported television and films. Other nations felt connected to the news coming from America, and America's agenda belonged to the rest of the world.

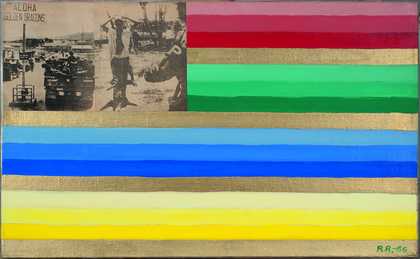

The Vietnam War was firmly in the sights of Finnish artist Reimo Reinikainen, with his series reworking the Stars and Stripes.

Reimo Reinikainen Sketch 4 for the US Flag 1966

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2015. Courtesy Turku Art Museum

Japanese artist Keiichi Tanaami became obsessed with movies, television and adverts as a young boy growing up in Tokyo, watching up to 500 hundred films in one year. He himself has drawn comparisons with his work and that of Warhol – citing Warhol as a huge influence after a visit to New York in the 1960s. With Japan still reeling from the atomic bomb attack in 1945, Tanaami turned his sights on the culture that was rebuilt in the aftermath of tragedy, and he still draws on this when making art:

Today, I still create works that deal with my experience of war as a child. This moment of fear that a whole city can disappear just within a moment is a memory that has been recorded deep in my mind; it does not go away.

Keiichi Tanaami Commercial War 1971, film still

© Keiichi Tanaami Courtesy NANZUKA, Tokyo

Strength in Numbers

Several works included in The World Goes Pop were by groups of artists working under one name.

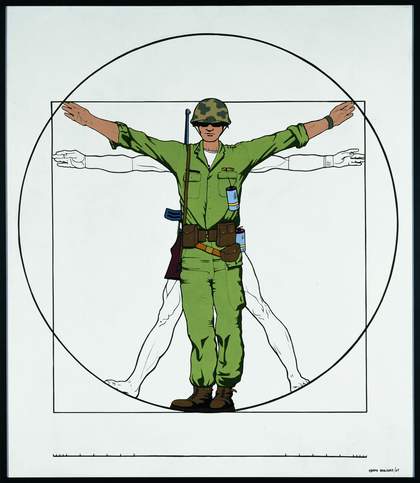

After years of civil war and living under General Franco’s regime in Spain, Joan Cardells and Jorge Ballester formed Equipo Realidad in Valencia in 1966. Far from adopting an introspective viewpoint, they explored Spain’s heritage and cultural traditions, examining them through the lens of modern society.

They used found imagery in their paintings. Robert Capa’s iconic photograph of a Spanish resistance fighter, Falling Soldier, and Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man are used in Divine Proportion 1967. Although they made work in Spain, Cardells said:

Our work was closely tied to current international events, more than national or local ones, because of censorship. We were cautious because censorship was watching us: we had a problem with a serigraphy of Che Guevara. But the critical stance was always above the local or the general.

Equipo Realidad Divine Proportion 1967

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2015

Another group, Equipo Crónica, comprised of Rafael Solbes, Manuel Valdes and Juan Antonio Toledo was also operating in Valencia at the same time. Formed in 1964, they also closely examined the changing face of the country they lived in. With a fascist party in power, these groups were critical of conservative doctrines and passionate about the role played by the artist in society. Their radical identity was reinforced by painting their own versions of famous Spanish masterpieces. Velazquez's Las Meninas was given a 1970s makeover, complete with patterned carpet, inflatable toys and a pot plant.

Equipo Crónica Social Realism and Pop Art in the Battle Field 1969

© DACS, London 2015

Rather than trivialising important motifs from Spanish culture, they focused on the collision between past and present, and the emergence of mass-produced domestic items. In 1969 they painted Guernica ‘69 made in reference to Picasso’s famous protest painting of the same name. Their referencing of famous images, popular culture and events in the political landscape in which they were living, was to them a way of protesting and resisting and the totalitarian state of Franco’s Spain.

2 by 2

Multiples, doubles, mirror images and diptychs featured in The World Goes Pop exhibition. These repeating formats reflect pop artists' interest in the mass production of homewares, cars, gadgets, fashion, music and even weapons.

Source material from advertising, music and film found its way on to gallery walls, elevating their status from the domestic and everyday, to fine art. Artists also experimented with techniques and image manipulation such as screen-printing and collage to make use of found images.

Kiki Kogelnik Hanging 1970

© Kiki Kogelnik Foundation Vienna/New York

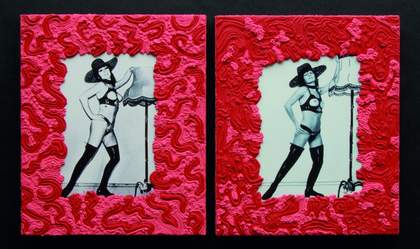

Artists are uniquely placed to turn a mirror on society at large and to broadcast back to their audience. Pop Art was something ordinary people could relate to. It was not elitist; it used symbols, materials, products and images that people identified with. It used things that could be found in the average home – in the kitchen cupboard or a photograph in a newspaper. Magazine and comic strips were widely used, and not just by Roy Lichtenstein, (as the history books may have you believe). French artist Dorothée Selz mimicked poses from a magazine to create her series Relative Mimetism. She highlighted the convention of using the female body as a sales tool and sex object, by placing the original and her new version of it side-by-side.

Dorothée Selz Relative Mimetism – Woman with Boots and Lamp 1973

© Dorothée Selz. MACBA Collection