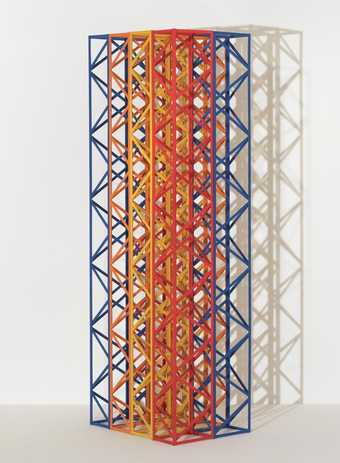

Saloua Raouda Choucair

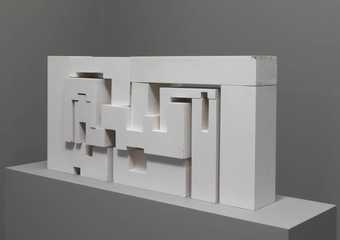

Composition in Blue Module (1947–51)

Tate

Introduction

When speaking about abstraction in art, the tendency is to think of a stylistic approach that flourished in Western art during the second half of the 20th century. Yet, geometric abstraction has been present in art, architecture and design in other parts of the world for thousands of years. The mathematic and artistic exploration of abstract geometric forms has spanned centuries from early modern artists and artisans working in the non-Western world up to conceptual artists in the 1960s and beyond. This interconnectedness of abstract forms can be seen in the works of contemporary artists coming from the Middle East or South Asia who engage with Western modernism whilst finding inspiration in the geometric principles of Islamic arts.

Artists, such as Rasheed Araeen (b. 1935), Saloua Raouda Choucair (1916-2017), Monir Shahroudy Famanfarmaian (1922-2019), Nabil Nahas (b. 1949), and Saleem Arif Quadri (b. 1949) have each in their own singular approach and practice engaged with abstraction by integrating elements of Islamic architecture, decorative ornaments, poetry, calligraphy or theology. Symmetry, seriality, intricate geometric shapes, and notions of the invisible and the infinite, characterise their creations.

All these artists worked or studied at some point in Europe or in the United States, where they were involved with the Postwar art scene during the 1950s and 1970s. As members of the diaspora, looking back at their cultural heritage from a distance and with a renewed gaze, they re-explored traditional elements in light of contemporary experiments. They suggest alternative perspectives to the universalist claim of western modernism by affirming the manifold and interrelated histories of abstraction and by transgressing its ideological implications.

Although their works may seem familiar to the Western viewer at first glance, they offer counter-narratives to established canons of formalist art. Playing with these canonical references, the works of these artists is far from being void of subject matter, or self-referential, but reconcile rational research on geometry and sciences with spirituality, cosmology, mysticism, Sufism and Sufi poetry. Their interest and engagement with traditional crafts and their use of multiple materials questions the established hierarchies between “high” and “low” art and the solely “decorative” or “ornamental” qualities of Islamic arts. From that perspective, abstraction can convey political or decolonial claims by expressing a firm commitment to the inclusion of different practices or minorities in the grand narrative of modernism.

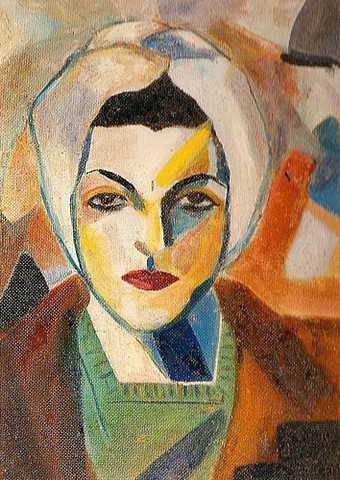

Saloua Raouda Choucair

(1916, Beirut, Lebanon – 2017, Beirut, Lebanon)

Saloua Raouda ChoucairSelf Portrait 1943© Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation

Saloua Raouda Choucair (1916-2017) is one of the leading figures of abstract art in the Middle East. Fascinated by natural sciences, mathematics, quantum physics, molecular biology and Islamic theology, Choucair applied both scientific and spiritual principles to her paintings and sculptures.

Born in Beirut and educated at the American Junior College for Women, she graduated in natural sciences and was trained by the Lebanese modernist painter Omar Onsi (1901-1969). In 1948, she travelled to Paris to study at the École des Beaux-Arts and frequented the studio of Fernand Léger (1881-1955). However, she rapidly broke away from his Cubist aesthetics to join a group of artists with whom she shared more affinities. Together with Jean Dewasne, Edgar Pillet, and Victor Vasarely (Vasarely), Choucair organised the activities of the Atelier d’Art Abstrait, which led her to become one of the first Arab artists to exhibit at the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles in 1951.

Working in Beirut in the late 1950s, she started experimenting with sculpture, creating three-dimensional geometric modular forms with clay or carved wood. Her sculptures, made of overlapping elements, are inspired by Arabic poetry, letterforms, calligraphy, Islamic architecture, abstract geometric patterns, as well as organic shapes.

In the 1960s, she created a series of sculptures she called “sculptural poems” such as Poem Wall (1963-65) in which geometric interconnecting elements recall the rhythm of poetic verses that each have their own meaning, while remaining part of a whole. The modular structure of these loosely connected forms on different levels also evokes architectural structures.

Her keen interest in architecture was ignited by a journey to Egypt in 1943 and can be seen in many of her works, such as Infinite Structure (1963-5) that consists of rectangular carved stone modules piled up vertically. Choucair’s sculptures activate the openness of forms in space, as they can be recombined and repeated infinitely. In Poem Wall, abstract shapes express movement, rhythm and exceed the physical object to express the invisible, a transcendence that links to Choucair’s artistic approach to Sufism.

Saloua Raouda Choucair

Infinite Structure (1963–5)

Tate

Saloua Raouda Choucair

Poem Wall (1963–5)

Tate

The Arab never took much interest in visible, tangible reality, or the truth that every human sees. Rather, he took his search for beauty to the essence of the subject, extracting it from all the adulterations that had accumulated in art since the time of the [Ancient] Greeks (zaman al-ighriq) until the end of the 19th century.1

Choucair, “How the Arab Understood Visual Art,” 190-201, published and translated by Kirsten Scheid in ARTMargins 4, no. 1 (2015): 120.

Throughout her career, she experimented with many different materials, such as wood, clay, fiberglass, aluminum, brass, plastic, plexiglas and stone (Intercircles, 1972-74). She always moulded her preliminary maquettes for her modular sculptures with terracotta. This all-embracing attitude towards different materials without making any distinction between them breaks away from the western distinction between fine arts and applied or decorative arts. The refusal of hierarchy between materials considered as “poor” such as wood or glass, in comparison to the more “noble” marble and bronze, is connected to her interest in craft, as she also produced enameled vessels, tapestries and jewellery (Silver ring by Choucair). Like other modern abstract artists from the Arab world, such as Etel Adnan (1925-2021), Kamal Boullata (1942-2029) or Samia Halaby (b. 1936), Saloua Raouda Choucair explored the intricate structures of Arabic Poetry, Islamic art, and sciences, while experimenting with contemporary abstraction. Her sculptures express a unique symbiosis of rationality and spirituality, which is mediated through intertwined intricate forms in a space conceived as being constantly in motion and infinite.

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian

(1922 Qazvin, Iran – 2019 Tehran, Iran)

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian

Something Old Something New (1974)

Tate

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian was one of the most prominent Iranian contemporary artists. Her works are based on the geometric principles of forms that relate to both western modern abstraction and to Islamic art and architecture.

Born in the city of Qazvin in Iran, she moved to New York in 1944, after studying fine arts at the University of Tehran. She was trained as a fashion illustrator at the Parsons School of Design, when the American Postwar art scene was vibrant and dominated by abstract expressionism and minimalism. In the early 1950s, she was designing fashion and painting floral compositions, while working for the department store Bonwit Teller, where she met the young Andy Warhol. She befriended artists such as Frank Stella, Barnett Newman, John Cage, Willem de Kooning, Louise Nevelson and started experimenting with minimalism, all the while turning towards other sources of inspiration from Iranian traditional art and architecture.

For me inspiration always comes from Iran, from my history, from my childhood, for better or for worse. I always go with the feeling of my eyes, and with my heart, and that is my main inspiration.

Monir Farmanfarmaian cited in: Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian: Cosmic Geometry, Hans Ulrich Obrist and Damiani Editore and The Third Line, 2011, p.22.

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian

Pentagon (2008)

Tate

A visit to the Shah Sheragh funerary complex and mosque with its domed shrine inlaid with pieces of mirror inspired her to renew the ancient crafts of mirror mosaics (aineh-kari) and inlaid marquetry (khatam-kari), which have been used in Iranian mosques and palaces since the 16th century. The interplay of light, reflection, movement, volume, repetition and symmetry of intricate geometric patterns in her compositions echo the mesmerising and dazzling effect of these animated and immersive spaces and their decorative vaulting (muqarnas) (Pentagon, 2008).

Something Old Something New (1974) embodies the encounter of Farmanfarmaian’s experience of traditional Iranian decorative arts with western minimalism. This composition structured by vertical and horizontal blue and green colored lines combines rectangular and triangular pieces of inlaid mirror and painted glass that create a mosaic surface of ever-changing volumes, playing with the viewer’s perception through light and motion. Decorative figurative elements with floral motifs and a bird counterbalance the overall abstract geometric arrangement and seem to allude to a past that has its place in this modernist experience.

Farmanfarmaian’s interest in traditional Persian decorative arts went beyond her artistic practice as she collected ancient decorative objects, jewellery and “coffeehouse paintings” (ghahve-khane). She collaborated with artisans throughout her career following the tradition of the kitabkhana, the collective workshop including artists and artisans in the service of the Persian court.

When the Islamic Revolution broke out in 1979, Farmanfarmaian resettled in New York until 2003, when she returned to Iran. Throughout her career, she received several public commissions, including a glass window for Tehran’s Senate building (1966), the Dag Hammarskjöld tower in New York (1981), and a multi-paneled installation, Variations on the Hexagon (2006), commissioned for the launch of the Jameel Gallery of Islamic Art at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. In 2017, the Monir Farmanfarmaian Museum opened in Tehran as the first museum dedicated to a female artist in Iran.

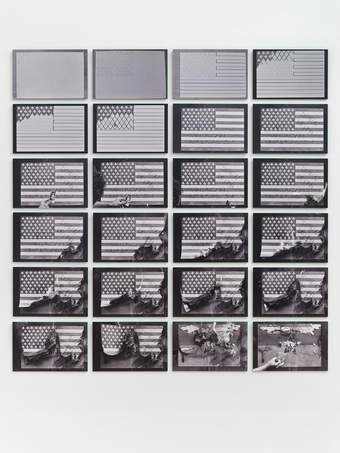

Rasheed Araeen

(b. 1935, Karachi, Pakistan)

Rasheed Araeen

3Y 3B (1969)

Tate

Rasheed Araeen is a multidisciplinary artist and a very important figure of postwar British art, as well as a writer and curator, whose work bridges conceptual art, activism and postcolonial theory. Rasheed Aareen remains a major voice of decolonial thought and gave visibility to non-western artists, notably by establishing the very influential Third Text review in 1987.

After graduating from the NED University of Engineering and Technology in Karachi, Araeen emigrated in 1964 from Pakistan to London, where he worked as a civil engineer. Although he did not receive any formal training as an artist, he created minimalist structures during the 1960s and was struck, in particular, by the abstract metal sculptures of Sir Anthony Caro (1924-2013) (Anthony Caro). The two artists shared an interest in simplified structures and industrial designs.

His interest in constructions, gridded patterns, and his research into geometric principles is informed by his experience as an engineer. This can also be seen in the many preparatory sketches he drew on sheets of squared paper with precise annotations during the 1960s and 1970s (Drawing for Sculpture series). From his activist performances in the 1970s (Chakras, 1969–70) and minimalist structures (Rang Baranga, 1969) to his works using the photographic medium in the 1980s (Fire, 1984; Bismullah 1988), an overtly political engagement and commitment to decolonisation lies at the heart of his artistic and intellectual research.

Following the killing of a young Nigerian man by the police in Leeds in 1969 (For Oluwale, 1971-73), Araeen wrote a manifesto (1975-76) which he considered a conceptual structure for collective action. The manifesto was later published in the Journal Black Phoenix, which he had founded together with the poet Mahmoud Jamal in 1978. The aim of the Journal was to promote a perspective on contemporary art and culture from the margins and to draw attention to the invisibility of non-British artists in London’s art scene:

The Third World artist is not seeking a position in Western art but his rightful place in the contemporary world which is being denied to him

Rasheed Araeen, Preliminary Notes for a Black Manifesto (1975-76)

Rasheed Araeen

Fire! (1975, printed 1984)

Tate

Rasheed Araeen

Rang Baranga (1969)

Tate

Araeen’s conceptual work echoes his writings and constitutes a response to the Eurocentrism of western modernism. 3Y 3B (1969) is a large bichrome wooden sculpture symmetrically divided by a blue and a yellow side on which wooden lattice elements are applied in the opposite colour of the painted panel. The wooden lattice recalls both industrial structures and traditional decorative elements that can be found in vernacular architecture and decorative arts in Pakistan. As Araeen’s minimalist structures also allude to social structures, they are often interactive and participative, like Zero to Infinity (1968-2007) that was conceived to be dismantled and reassembled by the viewers offering infinite possible reconfigurations.

Conclusion

Rasheed Araeen, as well as Saloua Raouda Choucair and Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, each through their singular expression and practice, have experimented abstraction in ways that challenge its conventional history. By creating artworks that integrate geometric elements of Islamic art and architecture, ornament, poetry and practices of craft, while engaging with western approaches and aesthetics of modernism, they bring to the fore the interconnected histories of abstract art, the contemporary dynamics of cross-cultural experiences, as well as new narratives that embrace difference.

About Nadia Radwan

Nadia Radwan, Ph.D., is an art historian, senior lecturer at the University of Bern. Her research focuses on transnational and global histories of the avant-garde, Middle Eastern modern and contemporary art, orientalism, and decolonisation in the museum. She is the co-founder of Manazir: Swiss Platform for the Study of Visual Arts, Architecture and Heritage in the Middle East and the editor-in-chief of Manazir Journal.

Research supported by Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational in partnership with Hyundai Motor