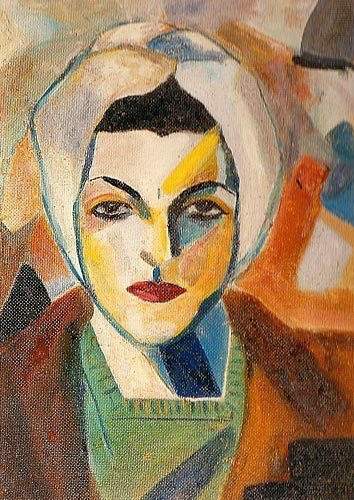

Saloua Raouda Choucair

Self Portrait 1943

© Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation

She always gave me tea, and oranges that came from someone’s orchard, not from China. She reassured me the oranges were grown without pesticides. Long before organic farming was a yuppie ‘must-have’, Saloua Raouda Choucair knew how ‘progress’ had gone awry and poisoned our Earth. She liked to make cookies with molasses and candied tangerine peel, and for the remainder of my days I will miss these delicacies. In the mid-1990s I was working on a book about her art and visited her studio often. These visits had the magic of flights in time. She told stories tirelessly, one leading to another, giggling at rather than bemoaning the many ironic twists of fate. At that time she had not yet received the acknowledgement and acclaim she craved and deserved. She was still making art, her mind was as sharp as a razor, but her ageing body slowed her down considerably. In the post-war art scene of Beirut, she had been relegated to the margins. In many respects, she was punished for not affiliating to trends, charming power-brokers and playing into the game of the country’s new breed of collectors.

The word eccentric draws its origins from middle English, and before that Latin and ancient Greek. It means exactly what it suggests phonetically: something – or someone – ‘ex-centred’, that has departed or broken away from the mainstream. Eccentrics don’t look the part. They resemble other people and seem to go about their everyday business more or less normally. Only once one is drawn to their proximity does one discover the extent to which they are singular and have had the courage to pursue their unconventional passions. Choucair was a real eccentric. Her big brown eyes sparkled with mischief even when she was well into her eighties, betraying something of her uncompromising nature. Immediately after greeting her, one suspected that this diminutive woman had been animated by a quiet ardour for a long time, and it had given her fearless inner strength and inexhaustible patience.

Until this day, the Lebanese visual arts world remains remarkably ‘virile’, populated by – and biased towards – men. Most artists are male, as are the majority of critics, writers and collectors. When, in the late 1940s, Choucair realised that making art was her calling, and decided to pursue academic training to become a professional artist, only a handful of others had had the courage to defy stringent social codes that assigned a role, place and rules of conduct to women. There were a few eloquent writers – novelists and poets – who had received acclaim for their talent, but never without a note of condescension. Invariably, class privilege afforded protection to those hailing from ruling élite families who broke rank and sought a university degree to become educators, scientists, nurses or physicians. Unlike Syria, Egypt, Iraq or Palestine, and in spite of a so-called historically liberal disposition, Lebanon was not a vanguard home to feminist movements, discourse or activists. Choucair was a stellar pioneer as a woman as well as an artist, especially considering she was born to the petite bourgeoisie, raised by a mother who was widowed at a young age. A tenacious perfectionist, her story becomes furthermore exceptional because she travelled abroad for more learning, challenging herself, as well as her male peers, to experiment and forge her own voice.

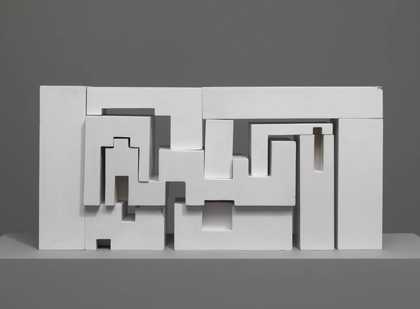

Saloua Raouda Choucair

Composition in Blue Module (1947–51)

Tate

Eccentric, Choucair was, but neither misfit nor agent provocateur. Her intellectual disposition was shaped by the scholarship of prominent thinkers of the Arab renaissance (Nahda) of the early twentieth century. A voracious reader, thoroughly curious, avidly seeking learning, she was in many ways a remarkably eloquent yet unassuming embodiment of an emancipated and sophisticated intellectual of her time.

Her work reconciled seemingly antithetical ideas and interests with a great deal of elegance. She was a feminist but not self-righteous, an Arabist but not a nationalist, a modernist engaged with the heritage of history, spiritual but not religious, philosophical but not a sophist, urbane but keenly fond of nature. She worked with her hands to sketch, paint and mould clay, while venturing into metal-smithing, wood-cutting and plastic moulding workshops, but also designed dresses for herself, jewellery, dinnerware and vases. She had that resourcefulness and playful wisdom of women who know how to make the best of their talents.

Choucair was imbued with the writings of Egyptian and Syrian feminists (women and men) from the turn of the twentieth century up until her own time. The grand themes and motifs that inspired her work were central to the pursuits and knowledge production of the Nahda, as well as her own intellectual contemporaries. For instance, the eminence of poetry as a referential realm for forging formal abstraction as well as unlocking meaning in modern artistic practice is not unusual in the Arab world, although her interpretation was certainly singular. To illustrate further, Choucair’s interest and engagement with Islam and its traditions were rooted in the bold secular scholarship of masters such as Taha Hussein.

In spite of the pervasive salience of postmodern and post-colonial theory, the story of modernity – or modernism – in the arts remains stubbornly Eurocentric. Attempts to revise canons have yet to permeate the mainstream. Even though the ‘east’ and ‘south’ – far and near – are credited with having inspired European masters to see, represent and abstract the world in wholly new ways, the language of modern art (Cubism, Surrealism, abstraction, Conceptualism, etc) is still attributed to a culturally dominant and self-centred Europe, and the artistic production by non-European contemporaries catalogued, studied and gauged in reference to, or as appropriations of, that European idiom. For instance, studies of the Surrealist movement rarely explore the lives and œuvres of the Egyptian Surrealists. Moreover, records, let alone acknowledgements, of what non-European artists, students or otherwise, contributed to conversations and exchanges with their Western peers in Paris, Rome or London are scant, vague or, at best, speculative.

One of the earliest principal conceits of modernity as a project in the intellectual and artistic fields was that it would be for artists and intellectuals across the world. Technological progress did not – supposedly – equate with spiritual or intellectual superiority, especially in the aftermath of the Second World War, when the so-called superiority of Europe had led to the barbarity of the Holocaust and the Hiroshima atomic bomb. Artists from the ‘east’ and ‘south’ endorsed that conceit and went seeking academic training in Europe, carrying their own cultural and intellectual heritage with pride of place. A cursory check of contributors to an issue of the Arabic-language Beirut-based publication Shi‘ir (Poetry) from 1957 shows Tristan Tzara alongside Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, both artists (poets, writers, painters). Choucair’s years of travel abroad and her engagement with the Western schools of modern art, as well as Islamic tradition and ancient Greek philosophy, were undertaken within this atmosphere of a rich, polyphonic and multilayered conversation. She was not cramped by a sense of inferiority, nor trapped in the ‘self’ and ‘other’ binary.

The modernist conceit of internationalism was no doubt politically naïve, idealistic at best, and soon enough the reality of the power divide between ‘north’ and ‘south’ was exposed, dissipating the illusions that beguiled the artists and intellectuals who endorsed it in the first place. Choucair was among those who came to understand the full extent of the perfidy of hegemony. But she had a lucid and sophisticated sense of knowledge production, political domination and the articulations of power. In one of the last letters she sent to a friend in Beirut from Paris, she outlines the contours of the critique of the Western view of the East that Edward Saïd would develop two decades later in his book Orientalism.

Saloua Raouda Choucair

Poem Wall (1963–5)

Tate

In fact, she began to distance herself from the mainstream precisely when discussion of modernism, westernisation and tradition became trapped in an anti-historical, essentialist and facile search for ‘authenticity’ in local modern iterations in the Arab world. Her artistic practice embodied the antithetical perspective that stitched continuities across time and unearthed resonances across cultures, affinities across idioms and media, and learning across disciplines, in the quest to unlock transcendental meanings of the universe and metaphysical secrets of existence. The more she worked, produced and reflected, the more immune she became to the distractions of fashion. And the less she attracted attention, the more wise an eccentric she became.

And she was right. She always gave me tea and oranges; and my memories have the aura of privileged tutorials with a masterful mentor. I have since aspired to become the sort of woman, like her, who will be remembered as exquisitely eccentric, fearlessly singular and tirelessly accomplished.

Rasha Salti is a writer, curator and international programmer for the Toronto International Film Festival. She lives in Beiruit and writes about art and film from the Middle East.